Bookish Diversions: Bound in Human Skin?

Plus Toxic Books, Macabre Origins, Books on a Wheel, Halloween Classics, More

¶ The skin I’m in. Fascination with true crime isn’t a recent phenomenon. Nineteenth-century Europe loved a ghastly murder tale. Take, for instance, the Parisian story of double murder that inspired Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment; it was a nonfiction newspaper sensation long before it was a novel.

Or consider the 1827 case from a village in Suffolk, England, involving William Corder and Maria Marten. Marten, a working-class single mother accustomed to disappointment had an affair with Corder’s older brother, Thomas. That didn’t pan out; Thomas drowned. At some point Marten took up with his younger brother, William, who promised to elope with her.

But, no. Instead, he murdered her and hid the body.

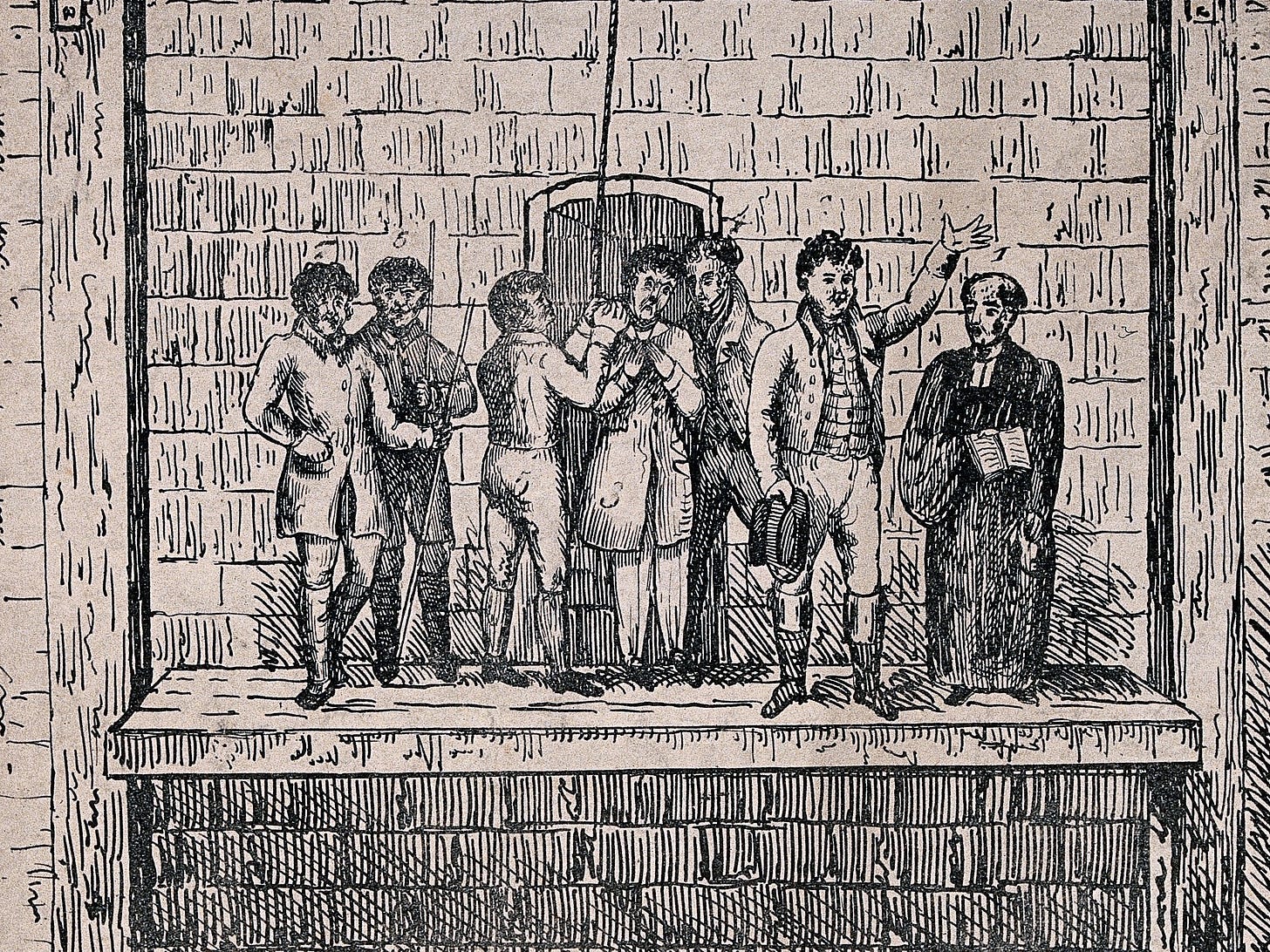

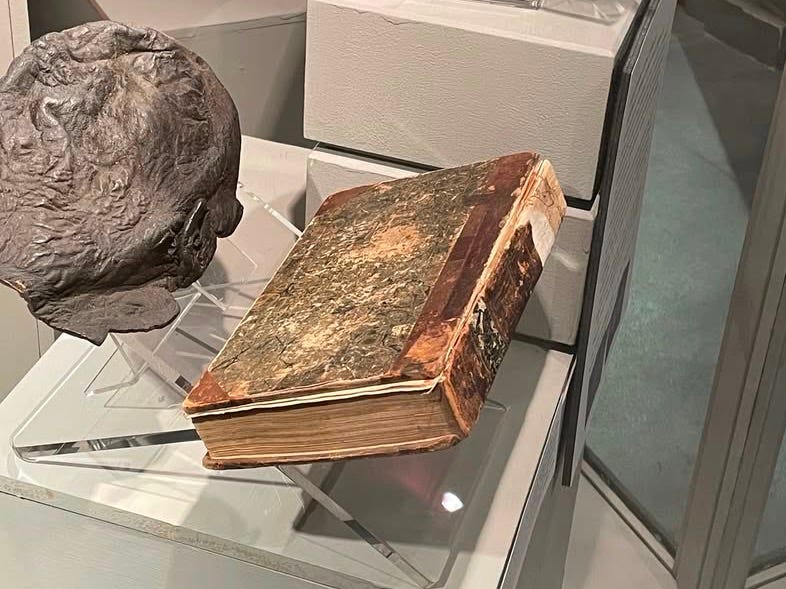

When the crime was revealed, the public couldn’t get enough of the story. It came to be known as the Red Barn Murder, named after the location of the killing and the place where Corder disposed of Marten’s body. William was convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged in 1828. But the strangest bit of all? When the account of the murder was compiled, they bound the book in William Corder’s own skin. It’s been on display at the Moyse’s Hall Museum since 1933.

Wanna see it?

If you killed someone in nineteenth-century England, there was a better than zero chance you’d end up flayed, tanned, and stretched around an account of your misdeeds.1 The same thing happened to John Horwood, hanged at Bristol Gaol in 1821 for the murder of Eliza Balsum. “Following his trial and execution,” reports the BBC,

Horwood’s corpse was dissected by surgeon Richard Smith during a public lecture at the Bristol Royal Infirmary. Smith then decided to have part of Horwood’s skin tanned to bind a collection of papers about the case. The cover of the book was embossed with a skull and crossbones, with the [Latin] words “Cutis Vera Johannis Horwood,” meaning “the actual skin of John Horwood,” added in gilt letters.

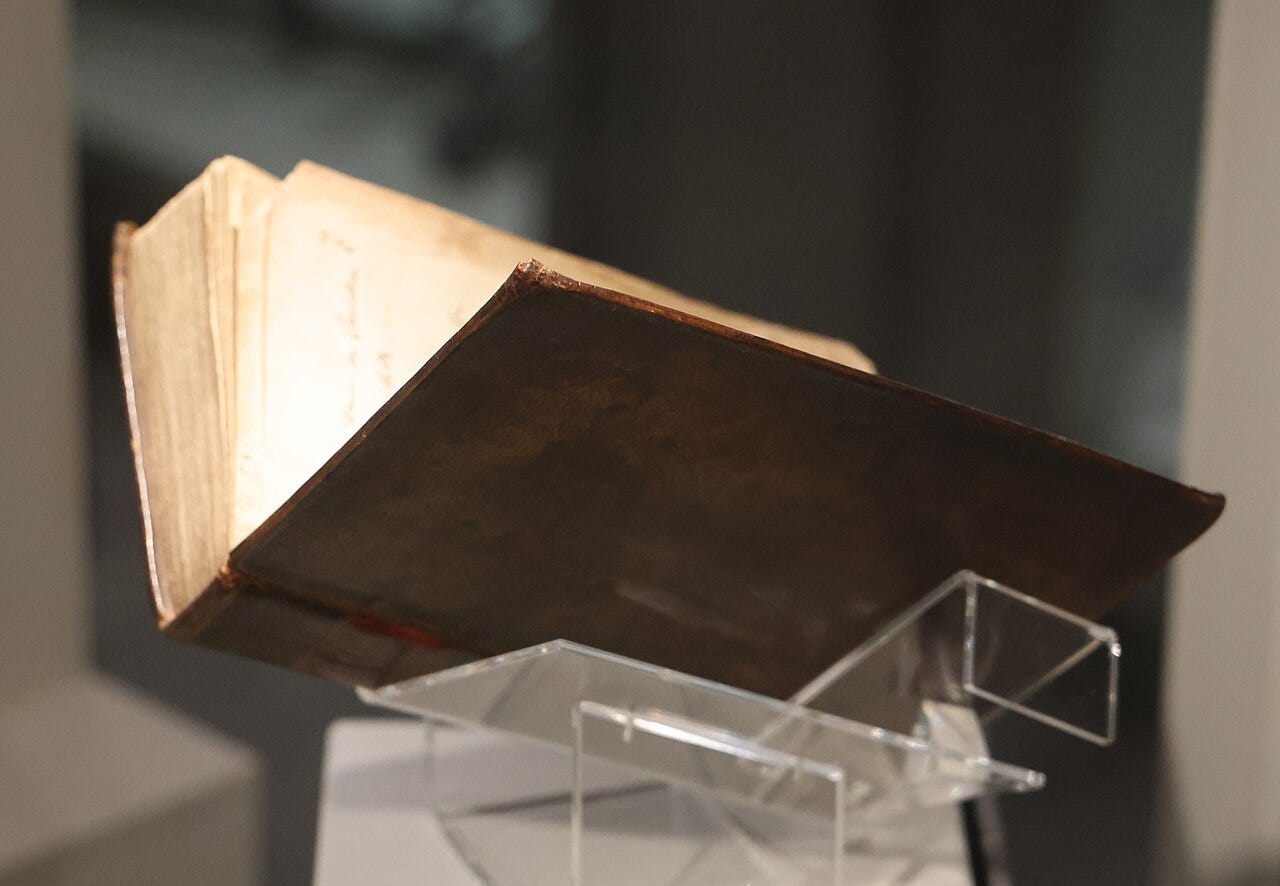

Last year, a second Red Barn Murder volume turned up, also bound with Corder’s hide. In this case, it wasn’t the entire thing, just the spine and corners. The book had been donated to Moyse’s Hall Museum about twenty years before by someone with a family connection to the doctor that skinned Corder back in 1828. Somehow, the book got lost in the shuffle. Once it was located, the book went on shudder-inducing display earlier this year, alongside Corder’s scalp. Yikes!

¶ Yes, there’s a word for that. As a practice, binding books in human skin goes back at least as far as the thirteenth century. It’s called anthropodermic bibliopegy, but according to an article in Popular Mechanics, the practice didn’t take hold until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. “By the 19th century, some doctors were binding anatomy books with human skin, considering it a ‘fitting gesture.’” Why?

There is much discourse among researchers as to why anyone did this. Some argue that it was a memorializing gesture, similar to keeping a loved one’s ashes. Others argue that doctors felt contempt toward their patients, feeling that the deceased did not survive society during life, and so must be useful in death.

The argument about contempt seems odd for medical patients but tracks for murderers like Corder and Horwood—one final step to ensure they got what was coming to them. Vindictive, yes, but it makes its own sort of sense.

But if the practice of binding books in human skin, especially for vindictive purposes, was grisly and gruesome in its day, what does that say about keeping them now and even putting them on display?

¶ Human remains. “These are two books I’d like to burn,” said Horrible Histories author Terry Deary about the Corder volumes. “I know you’re not supposed to burn books but quite honestly these are such sickening artifacts. What was worse than the hanging was the thought that their body would be dissected after death, and this is an extension of that.”

Burning the books seems extreme, but possessing such books does pose ethical puzzles. Harvard University made news when it decided to remove the human skin on one book in its possession, despite the glaring contradiction of simultaneously possessing some 20,000 other human remains. Critics aren’t happy.

Destroying the binding, said book scholar Eric Holzenberg, quoted in the New York Times, “accomplishes nothing” except advertising contemporary virtue over and above “the acts of people long dead.” I think that’s probably right. It’s more like moral grandstanding than anything. And it destroys the artifact, however it came to be.

¶ Are you even sure? One challenge, it turns out, is verifying that suspected books are actually bound in human skin. Sometimes a library or archive might believe human hide covers a book but doesn’t, as was the case of this volume once owned by Christopher Columbus; the actually binding turned out to be from the humble swine. This is where the Anthropodermic Book Project comes in.

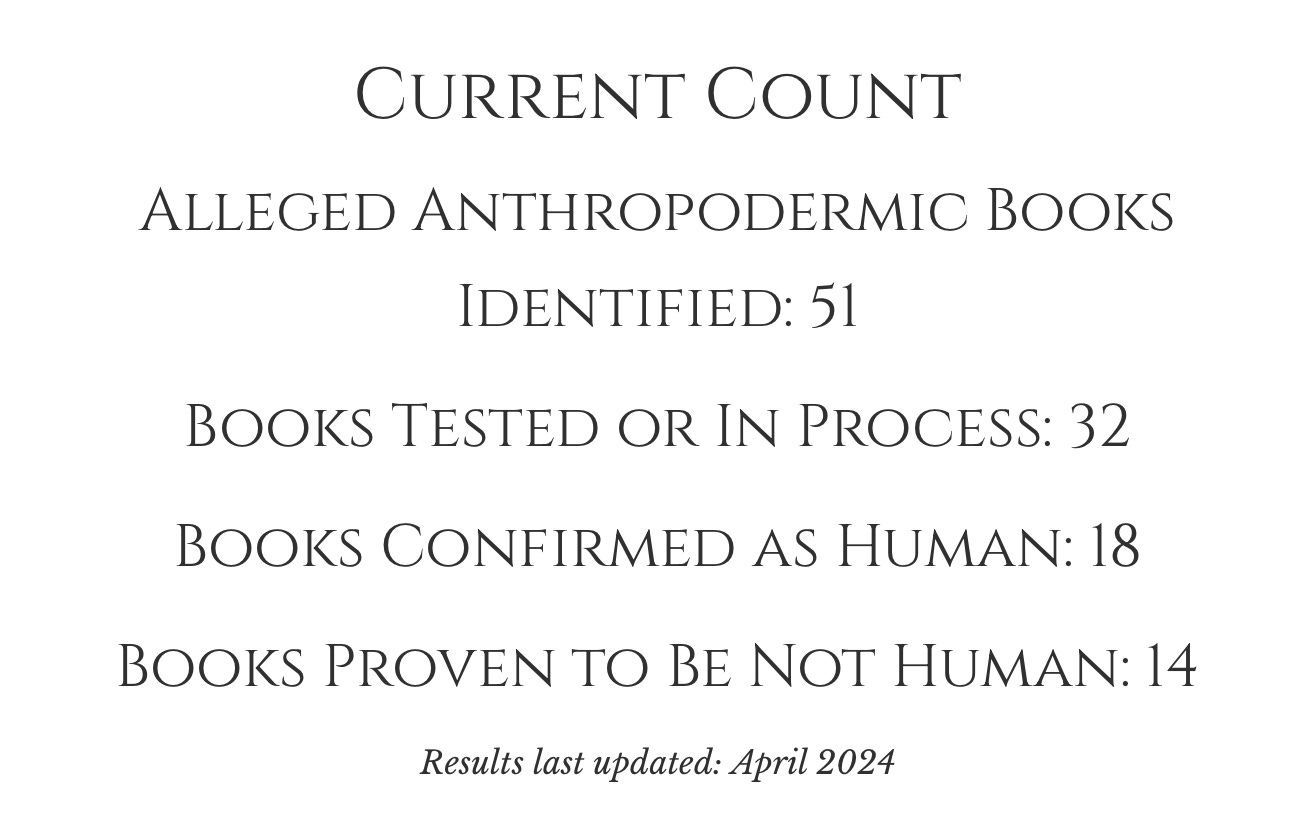

While their work is currently on hiatus, the Anthropodermic Book Project employs a method known as peptide mass fingerprinting to single out the species used in making leather, parchment, and book coverings. As of 2024, they’d tested 32 volumes assumed to be bound in human skin and confirmed 18 of those.

Mental Floss has compiled a list of eleven books confirmed as bound in human hide, including two copies of the poems of Phillis Wheatley: “It’s not known whose skin it is, who did the binding, or why they did it.”

What’s interesting is that out of 51 total books identified as possibly human-bound and the 32 tested, some 14 were not! Whatever reaction people have to possessing such books, their response might literally be—ahem—overkill.

¶ “Don’t lick your green book.” Books bound in human skin are grisly and gross, but otherwise harmless. That’s not true for the lovely emerald green books of the Victorian era, which owe their vibrant verdancy to . . . arsenic. In one analysis of 350 green clothbound books from the period, 39 contained the potentially lethal heavy metal.

The problem is that the color was hugely popular at the time and so arsenic potentially affects untold thousands of books on library shelves, in archives, and even gracing the shelves of collectors. From the Washington Post:

Curators [at the University of Delaware] use a method called X-ray fluorescence to investigate the chemical makeup of book covers. “It’s a device that looks like a ray gun tethered to a computer,” [Melissa] Tedone says. “Basically, you point the ray gun at the object, and pretty quickly the computer tells you what’s in it.”

About 50 percent of the books that have been analyzed have tested positive for lead, which is present in multiple pigments as well as pigment enhancers. Chromium has shown up in Victorian yellows, and mercury in the era’s intense reds. Arsenic, the most toxic of these chemicals, has been found in 300 books, including those with benign titles such as “The Grammar School Boys” and “Friendship’s Golden Altar.”

How likely will such tomes lead to tombs? Arsenic can irritate the skin but ingesting it is the real threat. “You probably have more dangerous things under the kitchen sink,” says Tedone. “You wouldn’t drink tile cleaner; don’t lick your green book.”

¶ The meaning of the macabre. All of this puts me in mind of the macabre. Where did that word come from? The Bible as it turns out. Says Dot Wordsworth (and is that name real?),

The French slang macchabée and the English macabre both originate in the danse macabre. There was a fourteenth-century French book called La Danse Macabré, with an accent, and Macabré seems to be an alteration of the Old French Macabé, a version of the biblical name Maccabaeus.

¶ The reason for the season. Naturally, you saw where this was heading: toward Halloween! A holiday I’ve never quite loved but have come to admire for its unapologetic flirtation with the ghastly and the ghostly. In truth, I’ve developed a deep respect for the literature of the macabre.

I’ve written about several works, mostly classics, that stop short of horror yet still unsettle the imagination. There’s something both valuable, curiously uplifting, and weirdly entertaining about that discomfort. Here’s a selection of several of those books I think are worth your time.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula;

Charles Williams’s many novels, including (appropriately) All Hallow’s Eve;

Shirley Jackson’s many novels, especially We Have Always Lived in the Castle and The Sundial;

Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes;

Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw;

Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; and

Anne de Marcken’s It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over.

It’s impossible to go wrong with any of those, and all of them can help frame the challenge of being human in unexpected ways. Come on! This is a world where they might use your skin to bind a book, and books can even kill. Best to be prepared.

¶ A 14,000-page book on a wheel? Of course, there are other options for binding books than arsenic and your grandmother. Here’s a video that recounts one surprisingly fun approach. What if you could take the 40 volumes of a beloved book series (Terry Pratchett’s Discworld), bind them all together, and place them on a circular-rotation device? This lady here did exactly that. Enjoy.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon, share it with a friend, and 💬 discuss it in the comments below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

Which naturally reminds me of the lyric from Rolf Harris’s novelty number, “Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport”:

Tan me hide when I’m dead, Fred

Tan me hide when I’m dead

So we tanned his hide when he died, Clyde

And that’s it hangin’ on the shed

I'm reminded of an old joke:

A man dies and his wife has him cremated, brings the ashes home, and carefully puts them into an hourglass. She puts the hourglass in a prominent place on the living room mantel, sighs contentedly, and says, "At last, you useless bum, you're going to work."

This is such a fascinating read! Thank you for sharing.

I was writing about the use of human skin to make a pair of shoes in Wyoming (that the doctor later wore to his Gubernatorial swearing in when he was elected to the post in Wyoming in the late 1800s) in a historical note for my historical fiction story (called The Sheepherder) on my Substack. It's such a weird bit of Wyoming history, but I had no idea that human skin was used at any point to bind books.