We’ve Been Reading ‘Dracula’ Wrong

The Gospel According to Mina Harker

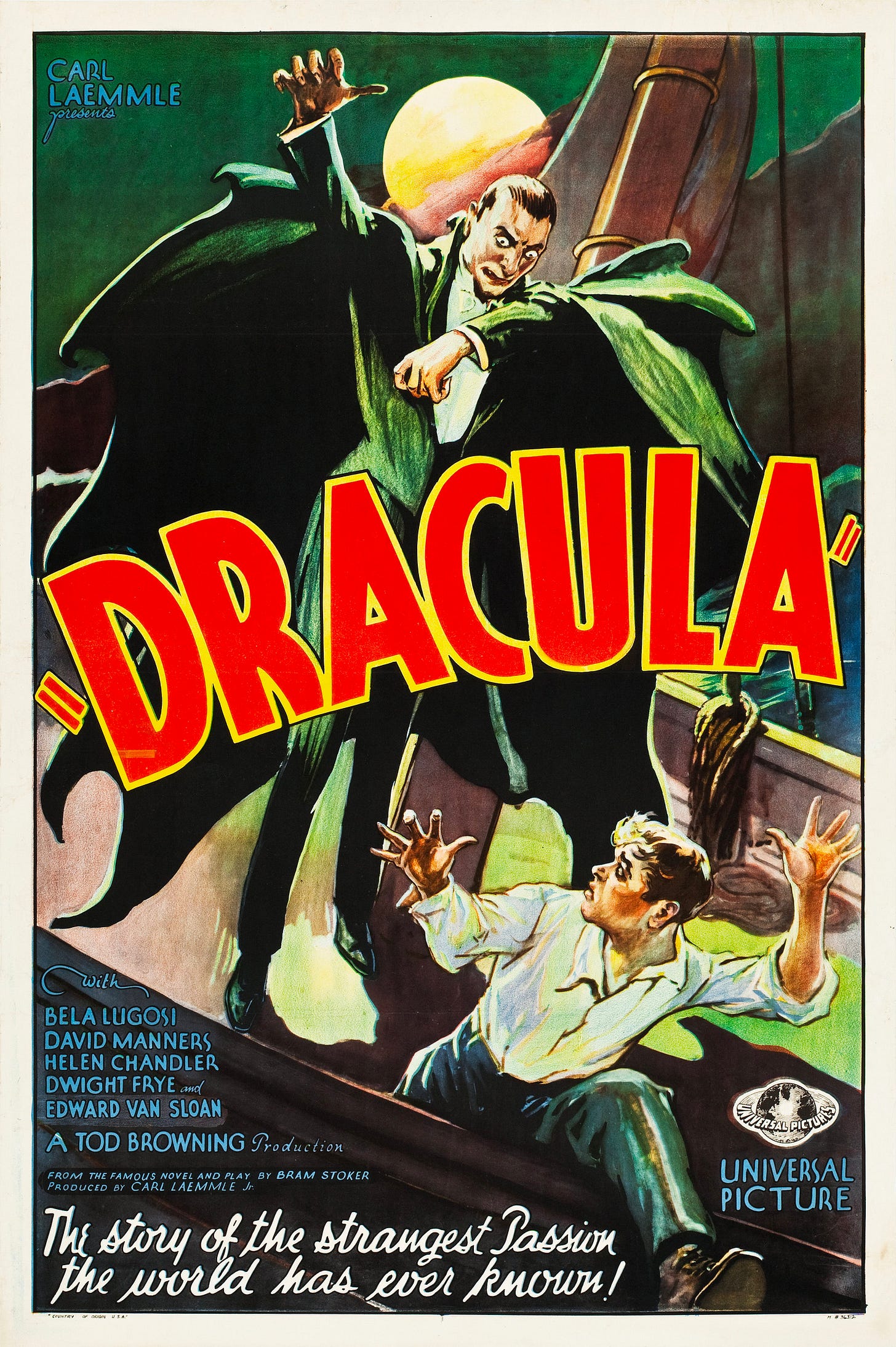

The name Dracula conjures a thousand caricatures, from the bloodcurdling to the comedic. I picture Gary Oldman’s sinister count in Coppola’s film—and also the becloaked villains of Looney Tunes and the pointy-toothed mathematician from Sesame Street. All of them are derivative; even Nosferatu’s Count Orlok exists only because the filmmakers couldn’t secure the rights to Bram Stoker’s original. Stoker didn’t invent the legend of the vampire, but the Irishman did almost single handedly ensure its fame.

The story, published in 1897 when Stoker was fifty, opens with the English solicitor Jonathan Harker traveling to Transylvania to finalize a real-estate deal for an aging nobleman named Count Dracula. From the first pages, the novel feels eerie and otherworldly—savage landscapes, superstitious villagers. When the denizens discover Harker’s destination, they cross themselves and warn him away. An old woman offers him her crucifix “for your mother’s sake.”

A good Anglican, Harker hesitates to accept what he sees as a bit of idolatry. Yet her fear unsettles him. “Whether it is the old lady’s fear, or the many ghostly traditions of this place, or the crucifix itself,” he writes in his journal, “I do not know, but I am not feeling nearly as easy in my mind as usual.”

Harker’s unease only deepens. The Count greets him with chilling politeness, but something is off: there are no servants in the castle, no other inhabitants, and Dracula never eats or drinks. Harker soon realizes he is a prisoner and the full horror of the situation stuns him—as, for instance, when he looks down from his window and sees the Count scaling the wall: “My very feelings changed to repulsion and terror when I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over that dreadful abyss, face down, with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings.”

Or worse, when he violates the Count’s prohibition and enters a forbidden part of the castle where he’s seduced and nearly killed by a trio of female vampires: “I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the supersensitive skin of my throat, and the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching and pausing there.” Dracula intervenes to save Harker’s life, but not for the sake of mercy; the Count has other plans for his guest.

All of this Harker records in shorthand in his journal. Stoker’s Dracula is told entirely through “found documents”: diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, a ship’s log, even transcribed phonograph recordings. Stoker modernized the epistolary form just as he reimagined the vampire myth. Instead of a framing device (such as, ”I discovered these letters in an old trunk”—yawn), he constructs the story from fragments the characters themselves compile. Mina Harker, a typist, gathers and transcribes the materials, shaping them into a single chronicle.

The method creates a pinprick immediacy. Using this narrative method, Stoker turns the reader into an active participant, holding the pieces and perspectives together and interpreting the story from the fragments left behind by its witnesses.

When Harker escapes and returns to England, the novel’s focus shifts. His fiancée Mina nurses him back to health, while her friend Lucy Westenra begins to waste away under mysterious circumstances. Dr. John Seward, who runs a mental asylum, consults his mentor Professor Van Helsing. The two men analyze Lucy’s strange case, gradually realizing science alone cannot explain her decline. Despite their efforts, Lucy dies—but not really, not fully. She has become one of the “undead” and escapes her tomb to prey upon local children.

A colorful posse of vampire hunters forms to stop her—Harker, Mina, Seward, Van Helsing, and others, including a Bowie-wielding Texan—and then turns to Dracula himself, now established in England. The Count requires his native soil to rest, shipped from Transylvania in large crates. The team tracks down and sanctifies the soil in each box, cutting off his means of regeneration. But Dracula strikes back, attacking Mina and forcing her to drink his blood. Unless he is destroyed, she too will become a vampire. The hunt leads from England across Europe and climaxes back in Transylvania.

Much of Dracula’s enduring power lies in a collision between ancient and modern worlds. The Count embodies the “old centuries,” as Harker puts it, with “powers of their own which mere ‘modernity cannot’ kill.” Dracula’s adversaries are doctors, lawyers, scientists armed with typewriters, phonographs, and telegrams. But when their data and analysis falter, they must resort to garlic, wooden stakes, crucifixes, and consecrated hosts. The novel becomes a confrontation between superstition and science, faith and empiricism—with a surprising resolution.

Amid all these crosscurrents, Mina Harker emerges as the true hero of the ensemble, the novel’s moral center. While Van Helsing dominates the popular imagination, Mina holds the narrative—and the intrepid crew of vampire hunters—together. Her discipline, intelligence, and compassion help keep the men focused. At one point she rebukes their thirst for vengeance, insisting that even Dracula deserves pity:

“I know that you must fight—that you must destroy,” she says,

but it is not a work of hate. That poor soul who has wrought all this misery is the saddest case of all. Just think what will be his joy when he, too, is destroyed in his worser part that his better part may have spiritual immortality. You must be pitiful to him, too, though it may not hold your hands from his destruction.

Jonathan won’t hear it. “If . . . I could send his soul for ever and ever to burning hell I would do it!” But Mina recognizes both the stakes and the deep solidarity of human suffering. Her reply is astonishingly compassionate:

Don’t say such things, Jonathan . . . perhaps . . . some day . . . I, too, may need such pity; and that some other like you—and with equal cause for anger—may deny it to me!

In that moment, Mina articulates the novel’s hidden theology: mercy over judgment. In Dracula Mina sees a mirror of her own corruption and appeals to grace rather than wrath. Dracula endures not only becuase it’s the source of so much popular media of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries but because it dramatizes profound human tensions: the mind divided between the ancient and the modern, and the soul torn between vengeance and mercy.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon, share it with a friend, and 💬 discuss it in the comments below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

While you’re here, check out:

And make sure to tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, and discover the preorder bonuses!

What a fine essay on Dracula. Stoker himself was immersed in the world of the Theatre and had divided feelings over Henry Irving (his model for Dracula). That Mina is the moral center had not occurred to me, but I think you are right.

Yesss all of this! 100% on point!

Have you listened to the podcast series on "Dracula" from House of Humane Letters? SOOOO good.