The Stranger Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

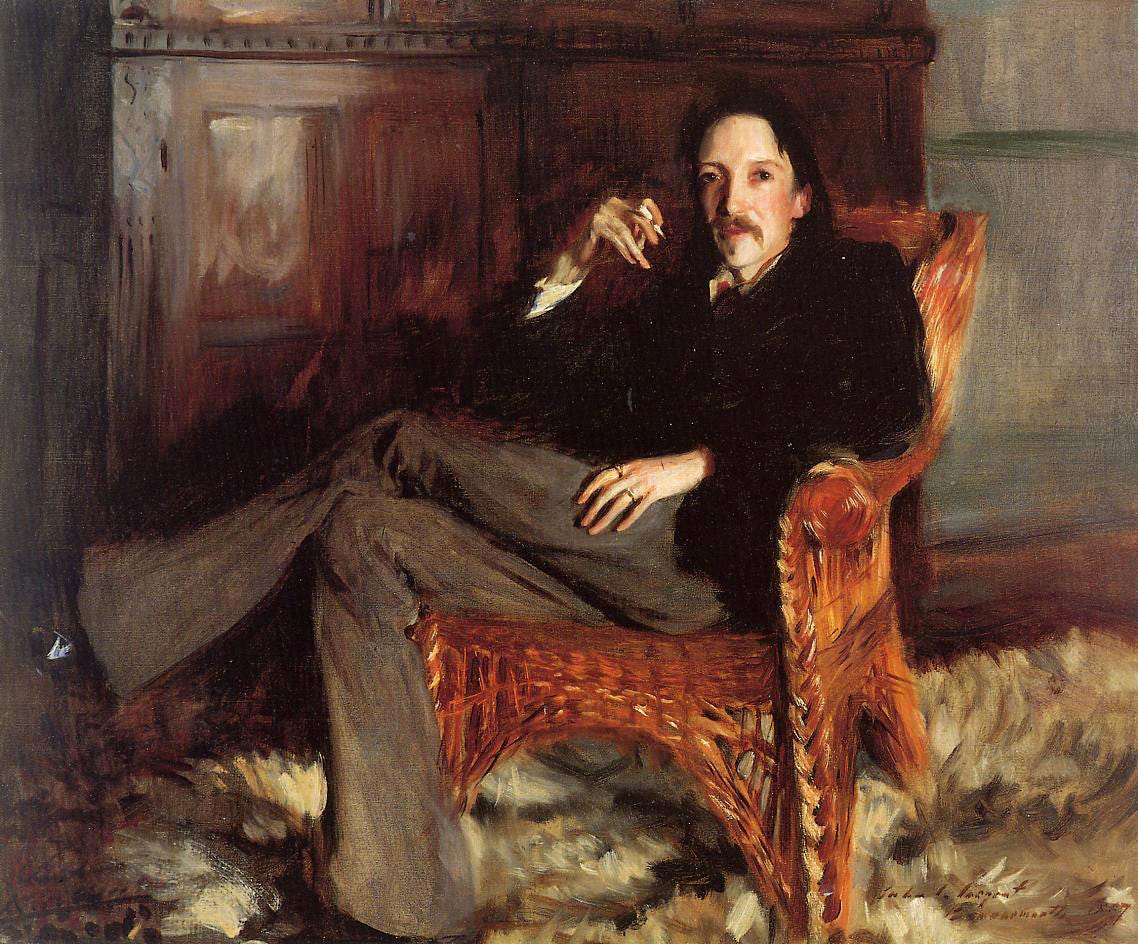

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Gothic Horror Story and the Possible Source of His Remarkable Powers

My first exposure to Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde wasn’t reading the gothic horror story for myself. I imbibed it indirectly, watching Looney Tunes as a kid. Those of a certain age will already have scenes flashing through their minds.

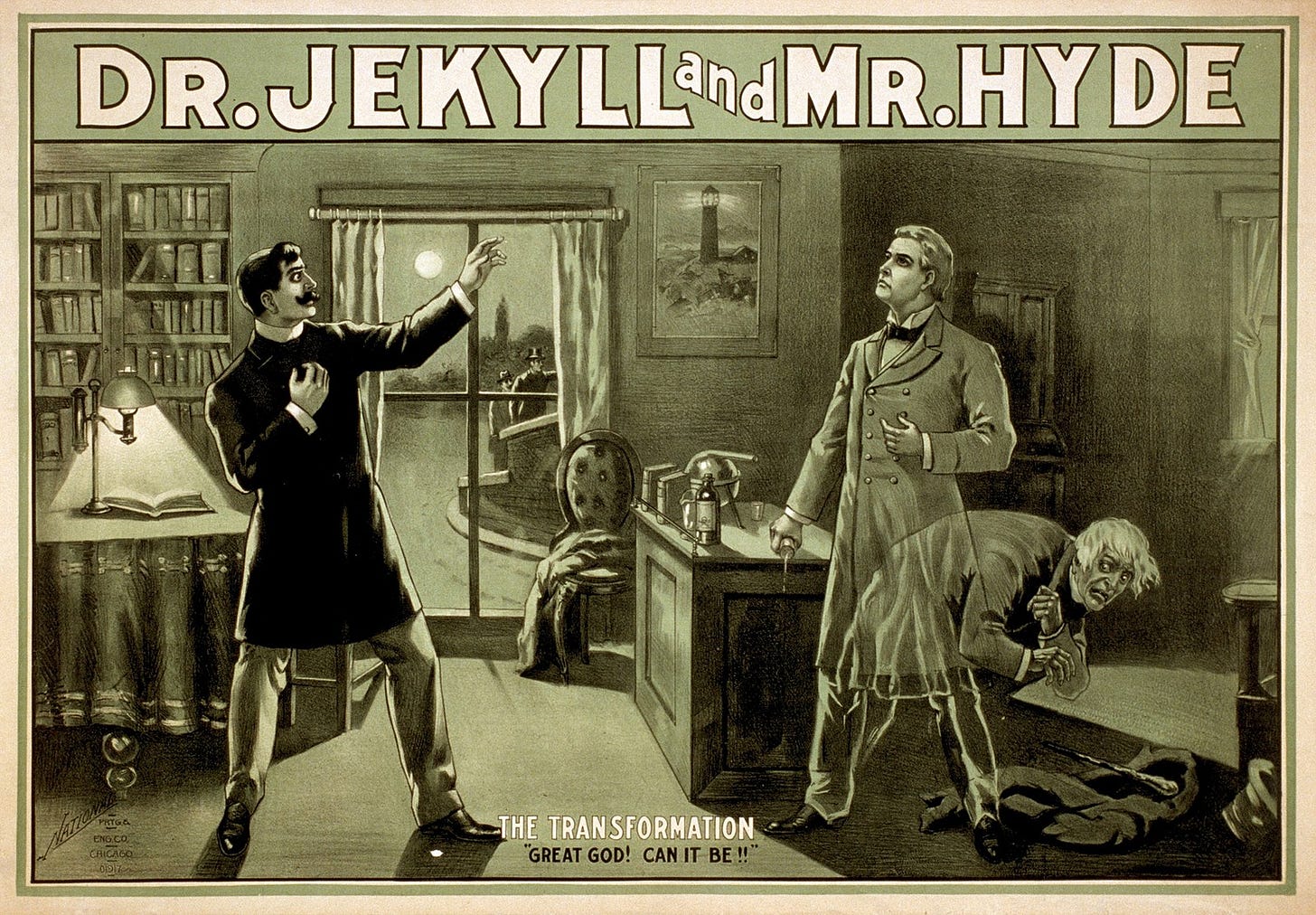

The creators put the novella’s idea of a potion that transforms a mild-mannered person into a monster to comedic effect in 1955 with “Hyde and Hare,” a short in which Bugs Bunny meets Dr. Jekyll in a park and returns home to his laboratory, whereupon the sheepish doctor turns into the knuckle-dragging brute, Mr. Hyde. Bugs eventually drinks the potion himself and suffers his own transformation.

Looney Tunes returned to this particular poisoned well several times. In one version Tweety becomes a monster; in another Sylvester goes feral. The Looney Tunes adaptations were just a few among countless others. By then, Stevenson’s story had long since burrowed itself into the public imagination, spawning endless variations and versions.

Written in October 1885 and published in January 1886, the novella was an instant sensation. In England it sold forty thousand copies by summer and God knows how many pirated copies in America. It still sells today. But the real strange case might have been the book’s initial composition.

Written in a Flurry

The story came to Stevenson in a dream. “I dreamed about Dr. Jekyll,” he told an interviewer. “One man . . . swallowed a drug and changed into another being.” His wife, Fanny, apparently woke him when she heard him screaming in his sleep. “Why did you wake me?” he complained. “I was dreaming a fine bogey tale.”

No matter. The rest of the story soon fell into place. “As I again went to sleep almost every detail of the story, as it stands, was clear to me,” he said.

He began writing feverishly, working day and night for three straight days without sleep. When he was finished, Stevenson presented the manuscript to Fanny. She dutifully read through it and rendered her verdict: No good. She thought it should be more allegorical and later reported she “wrote several pages of criticism pointing out that he had here a great moral allegory that the dream was obscuring.”

Stevenson retreated upstairs to ponder his options. Half an hour later Fanny found her husband staring at a pile of ashes in the fireplace. He’d burnt the entire thing, all thirty thousand words of it. Maybe. It’s also possible Fanny torched it. In a letter to one of the couple’s friends, she said Stevenson had written “a quire full of utter nonsense” and added, “I shall burn it after I show it to you.”

Regardless, Stevenson began rewriting the book from scratch, somehow managing the same brutal schedule as before—ten thousand words a day for three straight days with no sleep, after having just run the same punishing marathon.

What’s more, he performed this feat in diminished physical condition. Stevenson suffered from tuberculosis, was often bedridden, and lived on morphine. Recalled Fanny,

The amount of work this involved was appalling; that an invalid in my husband’s condition of health should have been able to perform the manual labour alone of putting 60,000 words to paper in six days seems incredible.

He was motivated. Stevenson was trying to get the book into print for the Christmas buying season. As mentioned above, he just missed it—but not for lack of trying. Working under a rushed publishing schedule, he was still making edits on the printer’s page proofs.

Confined to bed after the feat, he told his doctor, “I’ve got my shilling shocker.” He certainly did, and it’s that product of inhuman endurance that went on to become a category-defining, bestselling classic.

Split Personality

Stevenson had wanted to write on the duality of people’s nature and character. He just needed a device to pull it off. The dream provided it. But the teasing art of his unfolding narrative ensured the book’s success.

The primary character is neither Jekyll nor Hyde, but Jekyll’s attorney, Gabriel John Utterson. Out walking with his cousin, Utterson hears the story of how a man named Edward Hyde had, while running down the street, trampled a little girl. Passing the same house into which Hyde retreated prompts the memory.

But the key detail? Utterson’s cousin had pressed Hyde to pay damages, which he did, forking over a check signed by none other than Dr. Jekyll. Most troubling of all, Jekyll has recently named Hyde as the beneficiary of his will. What could be the relationship between his client and this brute?

Utterson attempts to find Hyde and speak to him for himself. After staking out the house, he finally encounters Hyde and confronts him. Little comes from the exchange except heightening Utterson’s suspicions that something is amiss. For starters, Hyde’s very appearance is offputting. “The man seems hardly human! Something trogladytic. . . . If I ever read Satan’s signature upon a face, it is on that face of your new friend,” says Utterson, speaking as if Jekyll were there with him.

When Utterson finally gets a chance to talk with Jekyll about Hyde, his client tells him not to worry. Everything is fine. What’s more, if Hyde is ever in need of help, Jekyll asks Utterson to see to it. Utterson reluctantly agrees and the mystery recedes—until Hyde is spied one night on an empty street clubbing an elderly pedestrian to death.

Sought by authorities, Hyde goes missing, and Utterson visits Jekyll to confront him about his rogue beneficiary. At this meeting Jekyll’s opinion of Hyde has changed. “I’m quite done with him,” he says. But a curious clue emerges: samples of Hyde’s handwriting which ominously matches Jekyll’s.

The curiosities mount from there. While Jekyll temporarily returns to his jovial, sociable self for a while, he eventually retreats to his laboratory and refuses to see a soul. Meanwhile, he sends his servant on futile errands to chemists for compounds to make drugs, none of which meet his standards.

Afraid for his master, the servant finally contacts Utterson for help. Returning to the laboratory, the pair break through the door and find Hyde, dead on the floor. And here at last the story finally falls out, thanks to a document trail left by both Jekyll and his estranged friend Dr. Lanyon.

We all know the gist, thanks to the story’s ubuiquity: Jekyll, an upstanding member of the community, concocts a potion that allows him to give liberal rein to his baser nature. When he consumes the draught, he transforms into Hyde and is free to act on any impulse he desires—but soon finds he has lost control.

Having loosed Hyde, Jekyll can’t manage him. Or if he could, those days quickly pass. Soon the transformations happen unbidden. Increasingly desperate and unable to find a remedy, Hyde suicides, letting the terrible truth finally emerge.

Stevenson leaves much unsaid in the story, permitting readers wide interpretive berth. And the tale invites many angles of analysis and appreciation: psychological, theological, spiritual, social, literary, and more. It’s no mystery why it became a bestseller and adapted into every sort of production, including kid’s cartoons. What is mysterious? That Stevenson managed to write the novel at all.

Fueling the Flurry

As mentioned, the writer suffered from tuberculosis. Beset and bedridden, he hadn’t produced anything of merit in a while. He lived in a house paid for by his father with Fanny and his stepson and couldn’t otherwise afford to live. He wrote a friend,

I have been nearly six months (more than six) in a strange condition of collapse when it was impossible to do any work and difficult (more difficult than you would suppose) to write the merest note. I am now better, but not yet my own man in the way of brains and in health only so-so.

He mentioned his “substantial capital of debts” and his work “still moving with a desperate slowness.” That was October 22. Some weeks before—though the letter is undated—he’d written another friend, “I am pouring forth a penny (12 penny) dreadful; it is dam dreadful. . . .” Pouring forth is an interesting expression for a writing spree.

By the end of the month, he’d finished not just one draft of Jekyll and Hyde, but, owing to his or his wife’s immolatory rashness, two. How did he do it? Financial straits can certainly motivate a man. But it hardly explains his frantic, energetic pace of composition. One suspicion? Cocaine.

Stevenson suffered from a hemorrhage, and cocaine—then touted as a wonder drug—was known to constrict blood vessels. Fanny regularly scoured the British medical journal, the Lancet, looking for any treatments that would help her husband, and cocaine was touted in the Lancet and elsewhere a miracle cure for all manner of illnesses.

As Dominic Streatfeild recounts in his history, Cocaine: The Unauthorized Biograpy, that winter the Lancet ran more than twenty articles on cocaine, and Stevenson’s stepson reported that his mother was “glued . . . to it.” We also know from a later letter Stevenson used cocaine to ward off colds.

It goes a long way to explain how an “invalid” who could barely “write the merest note” could manage to stay awake and write 10,000 words a day for six straight days. Its powerful effect, as Streatfeild wonders, might have even influenced Stevenson’s conception of Jekyll’s life-altering potion.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

While you’re still here . . .

Cocaine is a stimulant, and before the age of antibiotics, it was used medically to help those fighting deadly infections. TB is a bacterial infection, so it would make sense that Stevenson might be temporarily helped by the stimulatory effects of cocaine. The trouble is, and this was and is the danger for any patient using cocaine, it would also serve to more quickly wear out a heart that was already under great stress.

It would also have been very dangerous to mix cocaine with opium - overdose deaths are more likely to occur when a stimulant like cocaine is mixed with an opioid. A TB patient would use opium, not just for pain management, but to suppress that terrible hacking cough which is so exhausting and could exacerbate hemorrhaging. Stevenson, like all TB patients in that era, lived on a constant knife edge between life and death. No wonder so many of his works feel like nightmares. I speed read 'Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde' in adolescence, but that was enough to engrave all the gruesome scenes into my horrified brain and I have never read it again.

Very cool. Also anything with John Singer Sargent paintings is going to be worthwhile.