Tour My New Book, ‘The Idea Machine’

An Imaginary Exhibit: The Big Idea, Engines of Progress, Self-Creation, Generative AI, More

How might a museum curator design an exhibit around my new book, The Idea Machine, and what would it be like to visit? Step inside and find out.

What follows is a walkthrough of my book about books—the underrated information technology that built our world and shapes our future. As we grapple with slumping reading rates, increasing social discord, and the rise of generative AI, the history of the book has tons to teach us. It’s also pretty fun.

Entrance Hall: The Big Idea

Every museum has a lobby where you pop in, get your bearings, and pique your curiosity about what’s ahead. In The Idea Machine that lobby is the argument itself. My contention is that books represent more than containers for words. Rather, they’re humanity’s first great information technology.

A book is a machine—and one far more consequential than the steam engine or the digital computer. It doesn’t just store thoughts; it shapes them, orders them, and then unleashes them in the world. “If we equate the book with a machine,” write Carla Bozzolo, Dominque Coq, Denis Muzerelle, and Ezio Ornato,

it’s because this word evokes the concept of a “functional mechanism”: an arrangement of parts whose interaction tends to achieve a deliberately pursued result.

And what is that deliberately pursued result? “A book,” says I.A. Richards, “is a machine to think with.” Without books we have no history, no science, no law. Literature, philosophy, and religion are impoverished. Civilization depends on this humble contraption for preserving words. More importantly, cultural evolution relies the book as a principal engine of change.

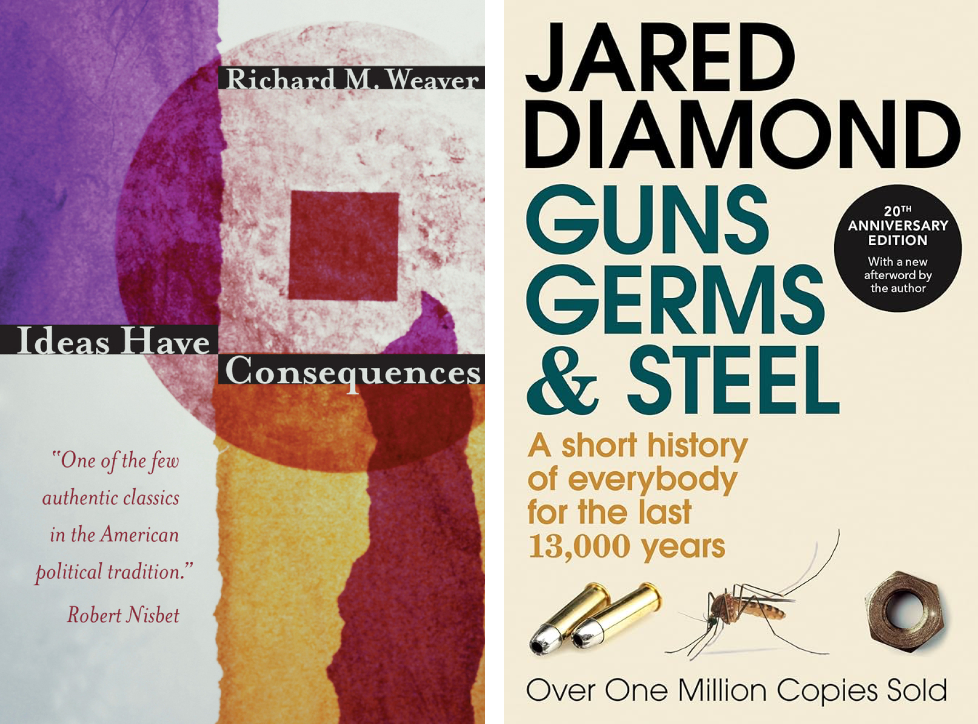

Scholars have sometimes focused on ideological answers for how we became modern. Spotting flaws in this approach, others have stressed material causes: economics, tools, even diseases. Compare, for example, Richard Weaver’s Ideas Have Consequences with Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel.

But I say it’s both; specifically, it’s the interplay of book content, format, and use that gets credit for how we thought and believed in the past and think and believe today.

The Idea Machine is a history of the book focused on how books have changed us—and how they continue to do so. A stroll through the five galleries ahead will help sketch the picture.

1st Gallery: Origins of the Book

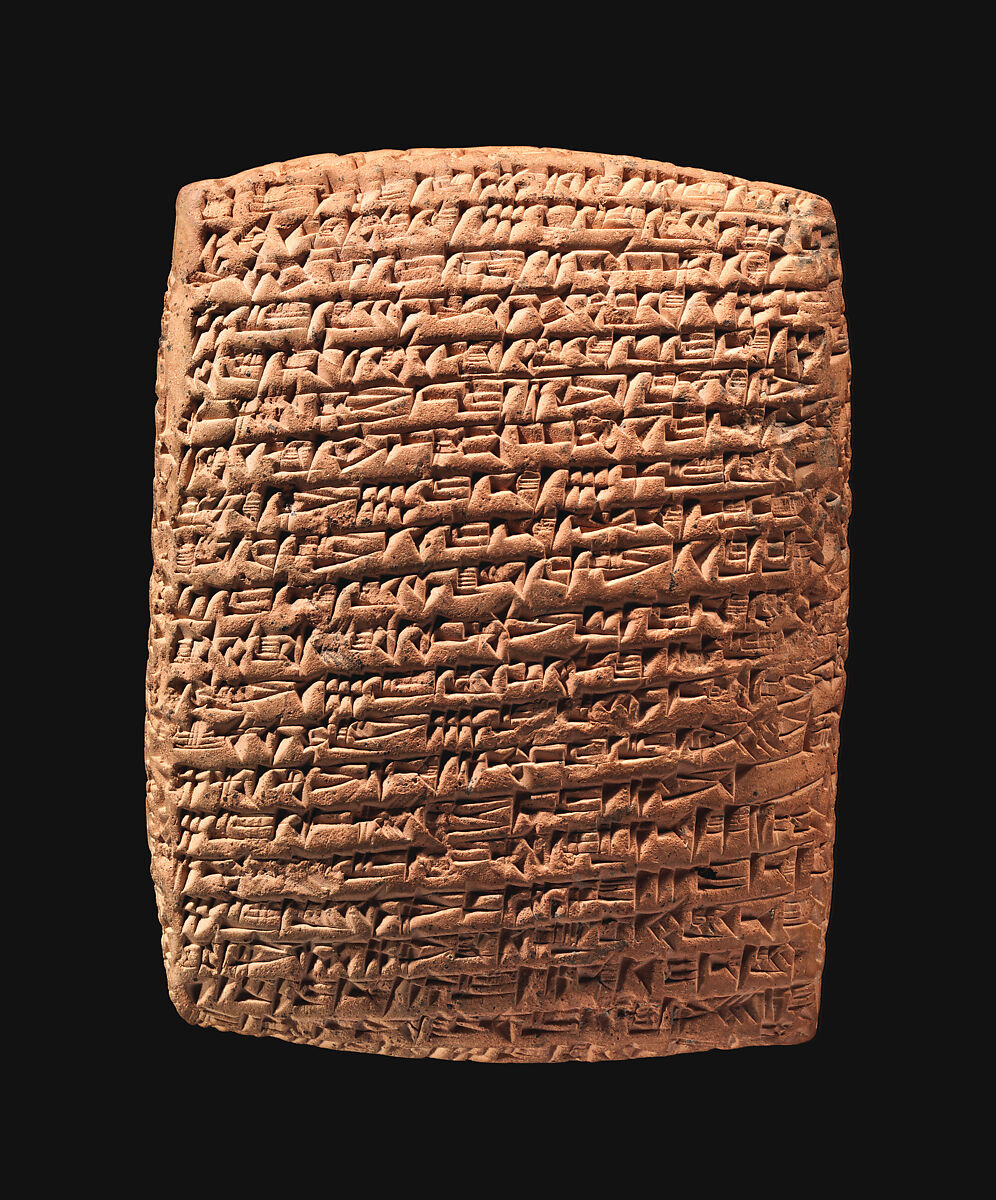

Our first gallery takes us back to the earliest implements of inscription—clay and wax tablets, papyrus scrolls, parchment codices. Forget the poets and shamans for a moment; writing began as a way to manage accounts, to add up who owed what to whom. Boring, I know. But writing had an exciting side effect; it facilitated the exteriorization of thought, serving as a prosthesis for the mind.

Socrates wasn’t a fan.

The philosopher complained that once words were fixed in a scroll, memory would atrophy. He was partly right. But everything comes down to tradeoffs: What did humanity gain with the shift to writing and books? Greater cognitive capacity—something from which Socrates actually benefitted himself, despite his protestations to the contrary. (We can even go so far as to call him a hypocrite.)

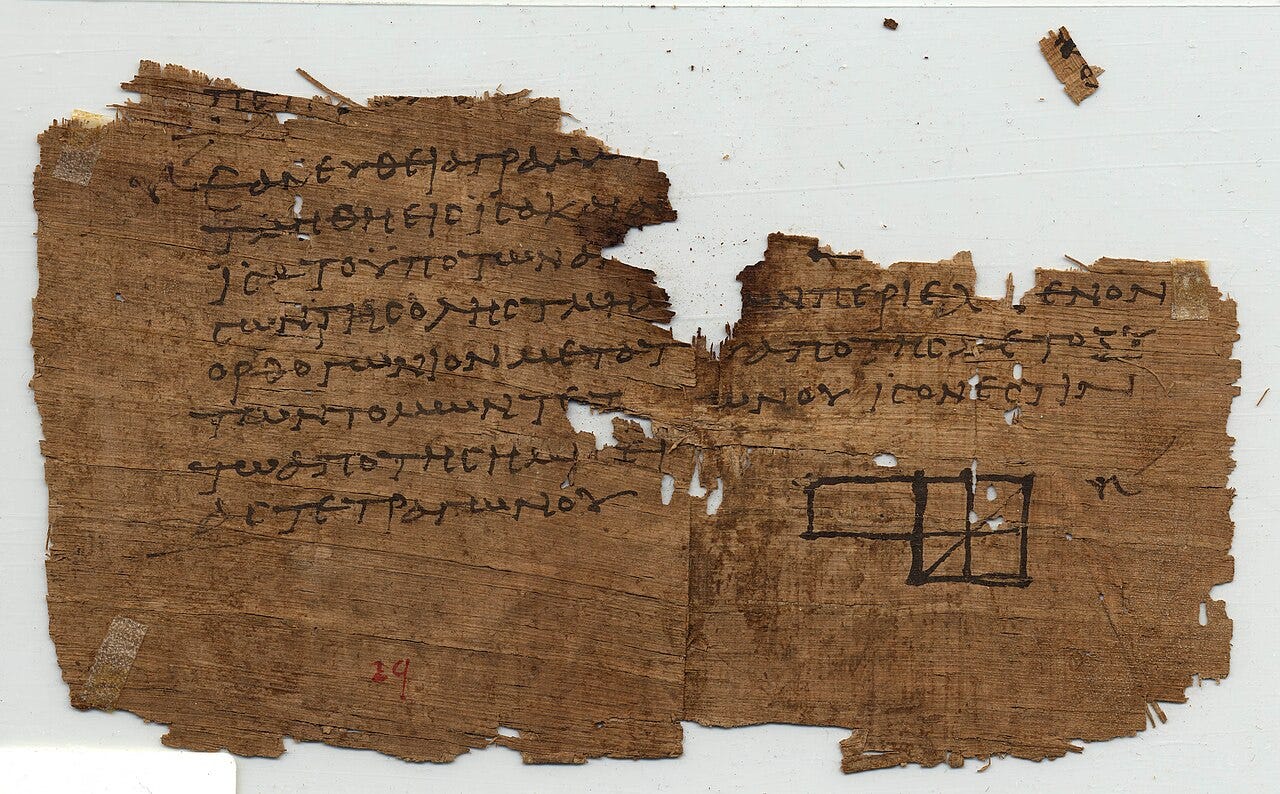

When captured on a page, language becomes objective, quotably precise, and subject to review, analysis, and revision. These sorts of gains compounded as the codex eventually displaced the scroll. Ancient Christians adopted the new format to gather letters and other writings into single volumes. Codexes offered increased capacity over scrolls, and the format slowly revealed other affordances as well: random access by flipping pages, indexing and cross‑referencing, visual organization of pages to structure data and guide attention, more functional marginal annotation, and plenty more besides.

These and other developments all served to advance human intellectual capabilities, which had a direct bearing on our cultural evolution. Every upgrade in hardware—from tablet to scroll to codex, from scripta continua text to spaced and punctuated lines—reshaped the possibilities of reading and writing, and with them the horizons of thought and action.

2nd Gallery: Engines of Progress

Excuse the commotion; this gallery gets noisy. Presses cycle, ink splatters, protests ring, and muskets fire. All that racket? It’s the sound of cultural acceleration—of civilization suddenly sped up by a device that not only copied texts but also multiplied their consequences, transforming books from rare artifacts into ubiquitous instruments, amplifying their reach across religion, science, and politics.

Start with religion. The publication of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses could have remained a minor spat in Wittenberg. Instead, the former monk’s masterful use of the press and emergent markets for religious literature catapulted his ideas across Europe, rattling Christendom to its foundation. The counterexample? At the same time Islam banned the use of the printing press for Muslims, keeping a tight grip on doctrinal orthodoxy—while inadvertently creating centuries-long cultural stagnation in the process.

Science similarly surged under the influence of print culture. Observations and arguments were no longer trapped in manuscripts. They could be tested, replicated, and contested by distant peers at scale. The scientific revolution involved print as much as epistemology; why else would Tycho Brahe equip his observatory with a press and paper mill? Newton’s Principia and Darwin’s Origin not only built on the work of predecessors and contemporaries—available thanks to commercial print networks—but those same networks opened them up to scrutiny, critique, and advancement.

Politics followed the same trajectory. Pamphlets armed revolutions. To highlight just one example, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense mobilized America’s political imagination toward independence. And Paine wasn’t alone. While the founders and their peers may have squabbled over any number of issues, they possessed more in common than their differences might suggest. Jefferson, Madison, Adams, Franklin, Washington, Hamilton, Rush, Henry, Mason, and so many others shared what historian Forrest McDonald called “a common matrix of ideas” shaped by English history and the transatlantic Enlightenment as accessed through “the printed word.”

Progress is a loaded term, and I use it—ahem—conservatively. But it’s worth saying that the revolutions that produced our modern world, however we regard them, wouldn’t have happened without the book. Ideas alone don’t change the world, but nobody changes the world without ideas.

3rd Gallery: Books and the Self

Quieter than our last stop, this room is no less revolutionary. Here the roar of presses gives way to the hush of slowly turning pages. The book’s influence shifts from public upheaval to private interiority.

In antiquity, reading was largely oral and communal, a performance staged before others. But as the technology of the book evolved with spaces between words, punctuation to clarify sense, and pages designed for easy navigation, reading turned inward. This shift reshaped both individuals and communities.

In the privacy of the page, readers could explore thoughts and feelings with a richness and depth otherwise inaccessible. Sequestered within this paper chamber of self-reflection, they could challenge accepted assumptions and entertain dissenting ideas. Scriptures such as the Torah and Gospels shaped collective identities, but because interpretations multiplied in irreconcilable ways, the same texts also fractured those identities.

And this was—is—only the beginning.

“Reading is,” says Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, “a technology for perspective-taking. When someone else’s thoughts are in your head, you are observing the world from that person’s vantage point.” Literature brings us into the orbit of other lives. If only for a few hours, we can appreciate their motivations and values; we can see what drives them, inspires them, and repels them. We can take the place of someone radically different from ourselves and engage the world as that self. As thriller writer Andrew Klavan once said, “It’s intellectual sex.”

It’s also, said C.S. Lewis, part of our moral enlargement. “Every act of justice or charity,” he said, “involves putting ourselves in the other person’s place and thus transcending our own competitive particularity.”

Books do that. And they do even more.

4th Gallery: From Gutenberg to Generative AI

In 79 CE Vesuvius smothered the library at Herculaneum in volcanic gas and ash, instantly reducing the scrolls to charred clumps of illegible carbon. Illegible, that is, until today when advanced imaging tools and AI can virtually pry apart the scrolls, tease out patterns of ink, and recover sentences lost for nearly two millennia.

But the connection between AI and the book? It runs much deeper than these miracles of restoration. At first glance, artificial intelligence looks like a hard and sharp break from the book, a foreign technology with its own logic. Step closer, however, and a surprising continuity emerges.

The human struggle has always been the same: not just too much to know, but too much knowledge to keep track of. From Ashurbanipal’s library at Nineveh—an attempt to capture and catalog the world on clay tablets—to monastic archives and scriptoria and the card catalogs of modern libraries, we’ve built tools to domesticate data, to manage the unmanageable. The internet was our latest grand attempt, a sprawling networked library, and generative AI is its companion: a system built to navigate, order, and re-present the flood of written material.

Large language models are the offspring of libraries, trained on millions of volumes, articles, and other documents. The book once extended human memory and refashioned thought; AI now confronts us with a similar expansion of capacity. It can summarize and compare across vast archives in moments. It can retrieve, recombine, and even propose ideas in ways that mimic and extend the operations of books themselves.

AI is best understood as a continuation of the idea machine’s long trajectory. To treat it as alien is to misunderstand it. Books were humanity’s earliest information technology, designed to preserve, organize, and transmit knowledge. AI is not a rupture but an extension of that project—with all its attendant promises and perils.

5th Gallery: The Bias of Books

This final gallery is about what books themselves encourage—not only by the arguments they contain but especially by their very existence, what they are and how they function. A book arrests language. It fixes words in place, and by doing so it allows readers to pause, return, compare. That permanence makes analysis possible. A sentence can be revisited; a paragraph can be dissected; memory no longer has to carry the whole burden of recall and argument because the page holds it all steady for inspection.

And because books can be read again, they invite criticism. They provoke the habit of questioning, of weighing one reading against another. Multiply the copies, and the effect grows: rival interpretations circulate, individuals within communities debate, societies learn to manage disagreement. Over time the result has been the cultivation of habits we now take for granted: free inquiry, toleration, even secularism. These were not natural outcomes of human goodwill but responses to the clash of interpretations in a world saturated with texts.

As a tool, books exert a bias of their own. By their very structure they lean toward openness, toward argument, toward imagination. They did not determine secularism or freedom of speech, but they have curved our culture those directions. As I demonstrate in The Idea Machine, the medium itself—content, format, and use—helped generate the dispositions that define modern intellectual and political life.

Gift Shop

Every museum tour ends with a stop in the gift shop. The best possible souvenir for this little jaunt? A copy of the book! If the concept of The Idea Machine resonates with you, if you love books about books, if you love history, if you love the story of ideas, the story of tech, the story of cultural change and cultural heroes, consider ordering a copy today.

Interintellect founder Anna Gát calls it “the best . . . gift you can get for anyone you know who loves books and ideas” (I bet that includes you). I’m as biased as they come, but I agree!

Thanks for participating in the community here at Miller’s Book Review 📚. If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe below.

Book nerds unite!

Fantastic peek into the book, Joel!I actually just read Nicholas Carr’s book “The Shallows” and there’s a great history of the technology of the written word/books in it that dovetails quite nicely with yours. I’m looking forward to reading it!