Would You Take Life Advice from a Zombie?

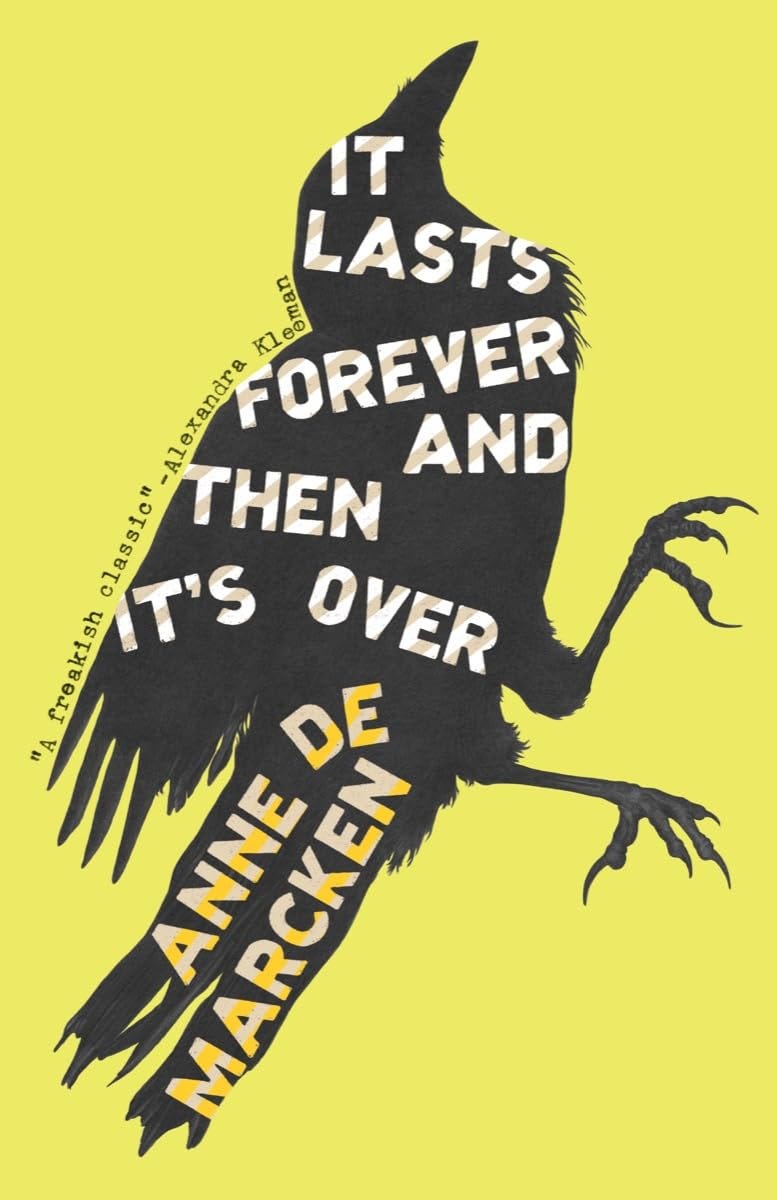

Reviewing Anne de Marcken’s ‘It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over’

How much of your life could you lose before you lose yourself? She lost her arm, the left one. She tries to keep it for a while but eventually has to give it up. Like her name. And her life partner. And almost everything else. Anne de Marcken’s unnamed narrator in It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over is dead.

But not entirely so.

She remembers loving someone and speaks to them often, communicating what few memories she retains, such as that time on the beach or trying to have a child. But they are long gone, inaccessible, and she plods on in a strange life after life.

Several others, all in the same condition, find themselves in a hotel, trying to reestablish a semblance of society among the residents. At some point they concoct a ceremony for the parts of their bodies they lose. The narrator at last parts with her arm. Having found a dead crow, she opens up a cavity under her ribs and packs it away like a prosthetic heart. The crow speaks to her, though she can do little with its terse opinions and pronouncements.

Bedeviled by hunger, she occasionally feasts on human flesh, though the experience leaves her feeling unsettled. She’s dead. She doesn’t need to eat. She recognizes that hunger masks a deeper need. “It is not hunger,” she says. “It is grief. . . . Hunger is only ravenous hope.” Arriving at this realization, she determines to fast. “I will no longer eat.”

She leaves the hotel and her companions, heading west. Why? Toward what? She doesn’t really know, but she moves, relentlessly, determinedly, all the while reflecting, thinking, puzzling on her existence. “We hold things in our bodies,” she says. “The earth holds things in its body. In clay. In ice. The real. The unreal. Time. Each other. All the chances we had.”

She meets no one on the road, eventually stopping at a ruined home with an abandoned outbuilding and an overgrown garden. While she reclines among the green, a scrub jay

lands on my forehead and tilts its head se we are eye to eye, and in that meeting a clue is conveyed that reveals a mystery that wasn’t a mystery until there was the clue. Not the kind of mystery that can be solved. Not a mystery of what happened or who did it or even why. This has all been known for so long. The kind of mystery that is a sacrament.

There is something of life, true life, conveyed in the exchange. She feels as though she’s holding onto the earth and that if she lets go she’ll spin off into space. And yet she decides to let go. But the feeling itself persists; she feels as though she’s both let go and still needs to. “This—this—is what it feels like to be undead,” she says. “And this is what it felt like to be alive.” The insight frees her to keep moving; westward she goes.

She abandons the few things she continues to hold, including her prosthetic heart, the crow which has kept her company for her journey. In the abandonment, she’s finally free to let her grief go as well, the grief of irretrievable loss—the lover now gone, the baby never born, the life that wouldn’t, couldn’t materialize—that has haunted her all along.

Though she reunites with the undead crew from the hotel, she departs again and now encounters the living who seek to dispatch the undead. Escaping their clutches, she meets a living woman with an undead child. She thinks to help but being self-aware decides not to offer advice: “I want to tell her that she doesn’t have to feed the boy. That maybe she shouldn’t. But you can’t tell other people how to parent, especially when you don’t have kids yourself.”

It’s one of many amusing moments in a grim but fascinating book. Should a zombie give parenting advice? Would you take it if they offered? Of course, if you found a meditative, metaphysical one like our narrator, you could do worse for parenting advice or any other sort, really. Consider these thoughtful questions and observations posed by our undead guide:

“Which comes first, the believer or a religion?”

“Maybe Mitchem is right about beauty. He says it persists because it was one of the few real things.”

“I never trust it when someone says ‘therefore.’”

“Grief is a time machine.”

“It was only after we had already resigned ourselves to the heartbreak that we realized it was just that we hadn’t gone far enough.”

“What is unbearable is already too much. How can there be more?”

Unless we’re talking about a mortuary manual, most books about death are really meditations on life, what makes it special, precious, and livable. It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over is that sort of book, a soft thriller, a slow-motion firecracker, a gradual revelation about the persistence of loss and the undying nature of love.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

While you’re here, check out these:

Phenomenal book title!

This is the best kind of review, which reveals the flavor without being the entire dish, so that one reader can comment that she is intrigued and another reader, me, can confidently say, “Not for me at this time,” in much the way that someone might be tempted to try a cilantro citrus salad that they otherwise would not have considered, while I can be happy to choose something else.