Just Like Yourself, Perhaps

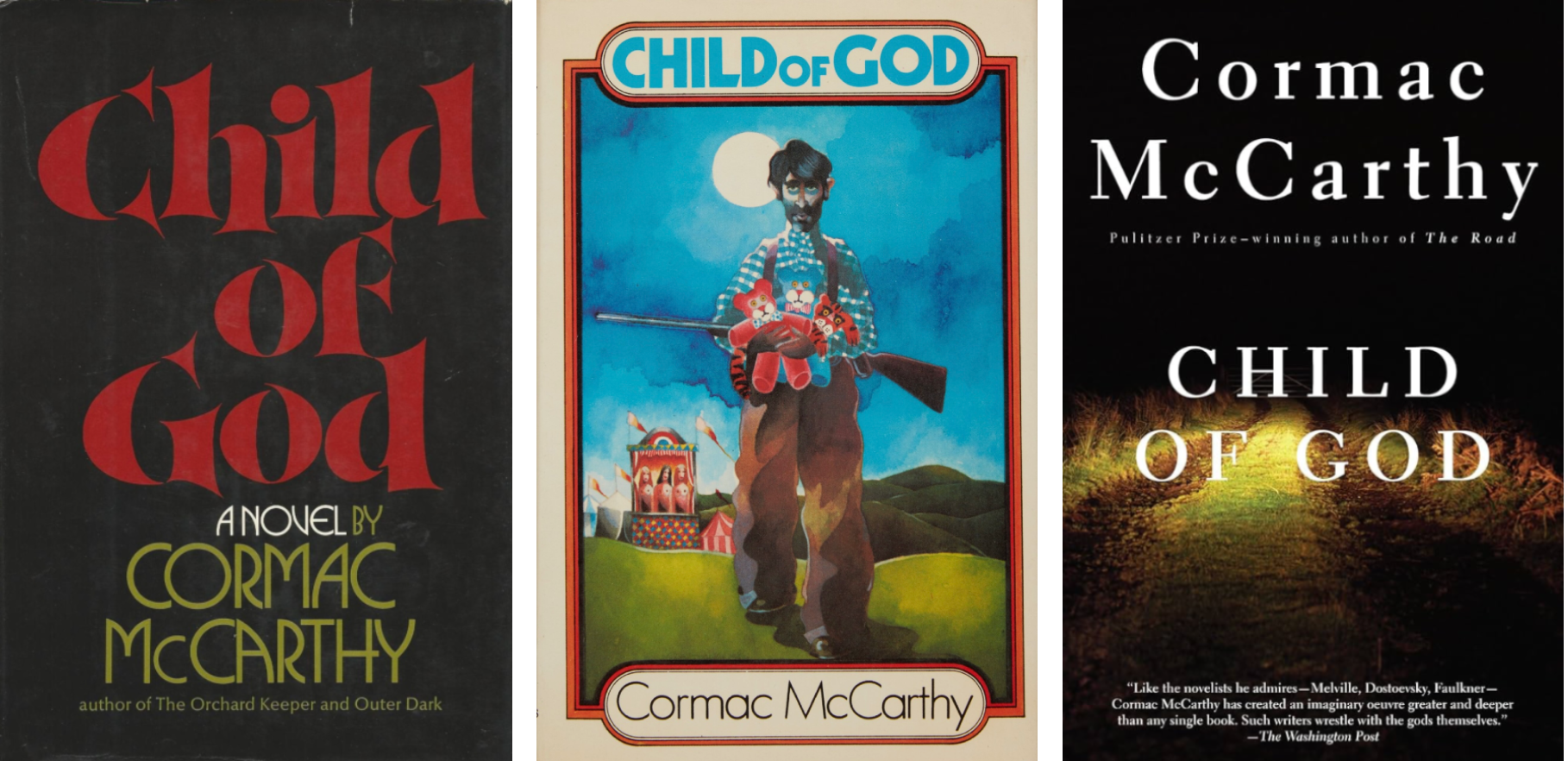

Hopefully Not! Reviewing Cormac McCarthy’s Gothic Classic ‘Child of God’

Cormac McCarthy’s gothic classic Child of God begins with a jab. When introducing the protagonist, Lester Ballard, McCarthy identifies him as “a child of God much like yourself perhaps.”

Better hope not.

Struck by the Jab

Within moments of meeting Ballard, we find him threatening a man tasked with auctioning away his family farm, nestled in the East Tennessee hills. Authorities intervene and give Ballard a beating from which, as the narrator tells us, he never fully recovers:

Lester Ballard never could hold his head right after that. It must of thowed his neck out someway or another. [Lest you flag my typo, McCarthy thows in plenty of Appalachian dialect, phonetic spelling, and grammatical quirks.]

Now homeless and edged from town, Ballard squats in an abandoned shack and tries to eke out an existence with no income, a complete deficit of social skills, and only one talent: the use of his rifle. Having squeezed every cent of credit and charity he can find, Ballard is left with nothing. Forced to the margins, he takes what he wants and hides in the hills.

The townspeople assume he’s capable of little better and assume he’ll do much worse. “What sort of meanness have you got laid out for next,” asks the sheriff after releasing Ballard from jail on a rape charge too flimsy to stand.

I figure you ought to give us a clue. Make it more fair. . . . I guess murder is next on the list ain’t it? Or what things is it you’ve done that we ain’t found out yet.

The taunt is part of McCarthy’s opening jab, the sheriff’s mix of cynicism and accusation easily fitting within that provocative perhaps, a capacious adverb that contains the entire drama to come: If we are children of God, like Ballard, what might this unhinged imago dei do?

The Spelunking Ghoul

McCarthy pushes Ballard—and those of us following his unspooling narrative—along a tightrope. Does social alienation drive Ballard’s sins, or do Ballard’s sins drive his social alienation? What of the traumas he’s endured, such as his father’s suicide? All these crosswinds blow through the story as Ballard descends into madness, murder, depravity, and bestial horrors some readers will want to avoid.

He’s already indulged one of those horrors when his shack burns down, forcing him to relocate to a cave—a descent both literal and figurative. Like an animal burrowing deeper into the earth, Ballard sheds layers of his humanity with every new crime and fills underground caverns with the evidence like a spelunking ghoul.

As the missing-person tally rises, the townsfolk suspect Ballard yet possess no genuine proof of his wrongdoing. Even after he’s finally injured and arrested for an unrelated attack, he denies any knowledge of the previous crimes.

When a lynch mob rousts him from the hospital and forces him to reveal the whereabouts of the bodies, Ballard begrudgingly agrees to help but then loses his captors in the twisting tunnels he made his home. Worming his way through the belly of the mountain, Ballard finally emerges after three days in a distorted resurrection, leaving his secret in the grave. Not until he finally dies does the truth at last emerge.

Yourself, Perhaps?

McCarthy reports Ballard’s crimes in stark and vivid language. Most readers will have no trouble ducking the jab: Much like myself? Definitely not. But McCarthy never fully deprives Ballard of his humanity, nor robs us of reason to sympathize with him.

In a comic scene at a carnival, Ballard uses his marksmanship to win three massive stuffed animals from a shooting gallery before the proprietor runs him off. Ballard cherishes the stuffed critters and carries them along from shack to cave. When a flood threatens his subterranean home, he rescues his prizes only to have them swept away, bobbing in the stream of a swollen creek. You can’t help but feel sorry for him—or laugh at the absurdity of a serial killer crying over his lost stuffies.

Then there’s the way Ballard’s treated by nearly everyone around him, from childhood on. His social ineptitude means his every exchange is negative, some especially so. Ballard is pathetic—pitiable, as a friend says—and you can feel your heart going out to him. Except for the killings. And worse.

No, he’s not like you, not like me. Not even close. Not even perhaps. Except. . . .

Slippery Slope

As the flood waters swamp the town, a sheriff’s deputy asks an old-timer about a violent episode in the area’s history. After hearing the tale, the deputy asks, “You think people was meaner then than they are now?”

“No,” the old-timer says after a moment’s thought. “I don’t. I think people are the same from the day God first made one.” If it’s uncomfortable contemplating our similarities to Ballard, it’s doubly so imagining that God created Ballard in his state of depravity—and that we share the same state: bad from the start, rotten at the root.

But does Child of God actually argue for such a grim anthropology? It’s better to contemplate our shared humanity, fallen from an elevated perch toward which we might again look, hope, and strive.

If we object to being compared to Ballard—whatever individual responsibility he bears for his crimes—McCarthy seems to say we have some communal obligation in pointing him back toward the possibility of elevation, rather than letting him slip further, or worse: giving him the final shove.

Special thanks to Derek Holser for the invitation to re-read this classic.

And thanks to you for reading! If you enjoyed this post, make sure to hit the ❤️ below and also share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Want more McCarthy? Check out these posts:

What a thoughtful and precise review. I read CMcC a long while back, and you have made me want to read him again, as a much older man. Blood Meridian scared the wits out of me. I expect it will do all the more now.

Wanted to thank you for this recommendation. I picked it up and read it after reading your post. It is dark, but his writing is compelling and "honest," and, as you say, it leads you along until you find yourself somehow rooting for Lester to survive. I suppose that's what makes McCarthy one of the greats -- he tells a dark tale so honestly that you can't help but get swept up in it. Peering at the world through the eyes of someone you'd loathe and fear in real life but who you can't help but find sympathy for in the pages of his books.

At any rate, always appreciate your recommendations and enjoy your reviews. Thanks for taking the time to share.