The Little Girl Who Helped Beat the Nazis

Childhood Remembered: Reviewing Betty Smith’s ‘A Tree Grows in Brooklyn’

Francie loves to read. She remembers when her eyes fell on a word and, for the first time ever, it meant something. She’d been learning all her letters, their sounds, and how they fit together. Then one day “mouse” jumped off the page—and “horse” and “running” and countless more. “From that time on,” recounts the narrator in Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, “the world was hers for the reading.”

As an adolescent Francie determines to read every book in the world, one each day starting with the A’s in her local Williamsburg, Brooklyn, library and working all the way down to the Z’s. On weekends she permits herself one deviation from the regimen: She asks the librarian to choose a book for her—though the woman, who never glances up from her desk, alternates between the same two suggestions week after week.

Back at her tenement Francie pulls a rug out onto the fire escape, props a pillow against the railing, and sinks into her book—the sights and sounds of the neighbors filtering up through the leafy canopy of the Chinese sumac (Ailanthus altissima, or tree of heaven) growing alongside her apartment building and makeshift roost.

Originally published in 1943, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is not driven by plot so much moments like this, built on the interaction of its characters, setting, and the myriad details that make up life in the borough from the turn of the century through World War I, all centered on young Francie Nolan, her mother Katie, father Johnny, and brother Neeley, but reaching out to include aunts, uncles, and grandparents.

‘Brooklyn . . . as It Really Is’

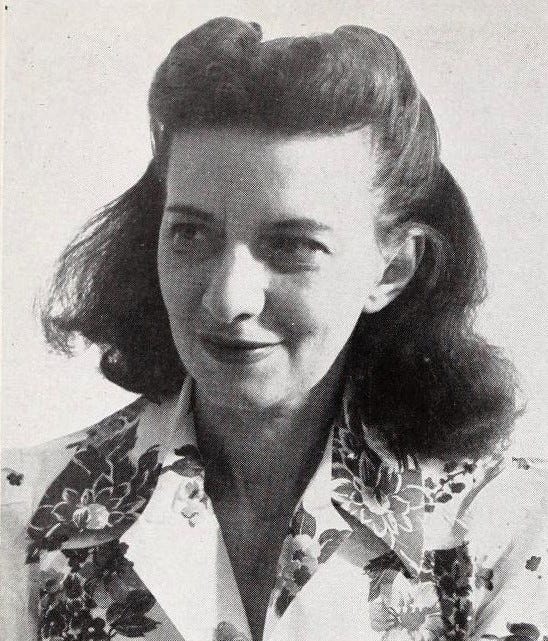

The book depicts fictionalized episodes and impressions of Smith’s own childhood in the neighborhood. Reading Thomas Wolfe’s short story, “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn” spurred her on. “I realized that he had caught the lost feeling of Brooklyn, but his stories weren’t authentic,” she said. “This challenged me to write what I know about Brooklyn, to show it as it really is.”

Smith scribbled an outline for what became A Tree Grows in Brooklyn on her copy of Wolfe’s autobiographical novel, Of Time and the River. Writing, as her daughter later recalled,

was all she did. . . . Often I’d get up at seven in the morning to get ready for school. . . . She’d be sitting in her bathrobe at the table she used as a desk typing away—she used a modified hunt and peck system, two fingers on each hand—that she'd taught herself. She was pretty fast at it.

There would be a cigarette in her mouth with an inch-long length of ash hanging from the end of it. She’d be so absorbed in her writing that she’d forget about the cigarette. Eventually the ash would just drop off and she’d absently brush it off her clothes.

Smith would rise an hour and half before the kids. She wouldn’t waste time getting the coal necessary to heat the freezing house. Instead, she’d lean her back on the side of the chimney to catch whatever residual heat was available from the prior night’s fire.

A novel wasn’t Smith’s original intention. Having moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in the middle thirties as part of the Federal Theatre Project, Smith edited books of plays and wrote dozens as well. She wrote and published more than seventy one-act plays, mostly for grocery money. But a couple of her plays won awards that paid $2000 in combined prizes, big for the day. Many of the passages and characters in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn started as material for her plays.

As she began reworking her material into a novel, Smith was convinced she had something special. Publishers disagreed. She sent lengthy passages to, among others, Random House, Houghton Mifflin, Scribner’s, and Little, Brown & Co. Rejection followed rejection until she entered the book into a nonfiction contest sponsored by Harper & Brothers in 1942—despite the book’s being a novel!

Elizabeth Lawrence, one of the first female editors at Harper, liked the book enough to treat it as a worthwhile submission in its own right. She eventually made an offer, and Smith accepted. Working with Lawrence, Smith brought the book into its final form and published it the following year.

A Family’s Story

The first part of the book introduces the Nolans and the their impoverished lives as the children and grandchildren of immigrants living in Brooklyn. Not that their poverty is completely apparent to the littlest of the bunch, Francie and Neeley. Their mother Katie transforms stale bread into a delicacy and turns going hungry into a game, pretending they’re exploring the North Pole, conserving their rations and awaiting resupply.

Part of the challenge? Francie’s father Johnny is an alcoholic. As a singing waiter he gets odd jobs but drinks too much to stay reliably employed. Katie must stand in the gap, cleaning three tenements top-to-bottom to cover their rent and pay for food. Johnny pitches in but keeps his tips for booze and drinks himself under a significant tab at his local bar.

Any extra money Katie and, later, the kids earn goes into a tin-can bank hidden in a closet. This strategy emerges in the second part of the book, which leaps back a decade or so to recount Katie and Johnny’s romance and early marriage. Francie’s grandmother encourages Katie to start stashing money to eventually buy land. It’s only one of her get-ahead strategies. Another? She recommends the kids read a page out of Shakespeare and the Protestant Bible—even though the family is devoutly Catholic—each and every day.

Education is paramount for the Nolans. That’s especially true for Francie who in part three enlists her dad in a scheme to transfer to a superior school in a better neighborhood. Francie’s grandmother is illiterate, same with her Aunt Sissy. But Francie not only learns to read, she becomes proficient, dreams of becoming a writer, and eventually works as a reader for a newspaper-clippings company—an analog predecessor of Google—though she’s only fifteen.

The reason for working so young? Johnny’s alcoholism causes his health to deteriorate. Shortly after hearing Katie is several months pregnant with their third child, he bolts the house, unable to imagine shouldering the new burden. He dies on the street of pneumonia a few days later. Suddenly, it’s all on Katie and the kids to make it work with a baby on the way and no help—however inconsistent—from Dad. The rest of the family rallies, and the Nolans’s fortunes begin to turn in parts four and five of the book.

All of this could feel melodramatic or sentimental in the hands of a less capable writer. But Smith pulls you so convincingly into the world you don’t question it for a moment. Her use of vivid description, unforgettable characters, and comedic episodes (such as when Johnny takes the kids fishing, knowing nothing about how it’s done, or when Aunt Sissy “got herself widowed, divorced, married, and pregnant—all in ten day’s time”) carries you along in utter fascination.

Remarkably, that fascination started before the book even released.

Immediate Success

Harper & Brothers editor Elizabeth Lawrence knew she had a hit on her hands but had no idea how big. Early enthusiasm meant the book went into a second printing prior to its official publication. I’m not sure how the publisher kept up with demand; within two weeks of release the book had sold 150,000 copies, eventually moving more than six million!

One reason for the ongoing success of the novel was the decision by the Council on Books in Wartime to release an Armed Services Edition for the benefit of American troops stationed overseas in WWII. It proved one of the most popular novels in the program, according to Molly Guptill Manning, whose history When Books Went to War recounts the story and impact of ASEs.

Soldiers loved it. Manning tells of servicemen reading the pocket-sized edition everywhere from Army hospitals to the front, flipping through pages between bursts of enemy fire.

They wrote Smith constantly. “I haven’t laughed so heartily since my arrival over here eight months ago,” said one. Many noted how much it made them homesick. One said it was like receiving “a good letter from home.” Another compared the book to “living my life over again.” Smith received several letters a day from servicemen—about 1,500 a year—and dutifully responded to most.

In many ways Smith’s book embodied the Allied powers’ civilizational struggle against the Nazis. Instead of a society purging its supposedly lesser elements, the American project welcomed all sorts (even if ambivalently) and incorporated them (even if imperfectly) into itself, as they busily contributed to the whole. Coming when it did and read in the context of war, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was both a rebuke and a declaration. And it resonated.

“In the end,” according to one account, “the novel grossed [Smith] about $1 million.” Not too shabby for the daughter of German immigrants—a juicy irony given the book’s role in the war. And, of course, it still sells well today.

What explains its impact and longevity? Unlike Thomas Wolfe’s Brooklyn story, Smith’s was authentic, largely because she lived so much of it. Just like the tree of heaven—that Chinese sumac growing tall outside Francie’s window—Smith’s characters, her neighbors, even her own family began as a foreign (some would say invasive) transplant but quickly took root, becoming thoroughly American.

And countless readers affirmed her compelling portrayal after seeing their own experience refracted through carefully crafted pages that still move readers today.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is the twelfth and final book in my 2023 classic novel goal. If you want to read more about that project, you can find that here and here. In all, I’ve read and reviewed:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (January)

Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (February)

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (March)

Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (April)

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (May)

Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (June)

Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy (July)

Zora Neale Hurston’s The Eyes Were Watching God (August)

Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (September)

Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (October)

Shusaku Endo’s Silence (November)

As soon as I finished Silence I jumped into Endo’s The Samurai, even though it wasn’t part of the original goal. It wasn’t the only bonus book.

I ended up including a few other classic novel reviews this year: John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids, plus a roundup of several others by Wyndham, along with Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

And I may not be done yet! There are several weeks left on the year. Turns out classic novels are a bit addictive.

It's a great, great book, which I define in part by the surprises it has, such as the segment in which the reader dreads that Francie is about to be raped, but the young man turns out to have no ulterior motive, after all.

Anytime anyone mentions that book, good citizenship and a love of art ( 99% the latter ) obligates me to mention that the book was turned into a musical by Arthur Schwartz and Dorothy Fields in 1951. As one Broadway historian has said, it's a canonical cast album, and it's unfortunate that the show itself was not a success. The producers had the coup of getting the great actress, Shirley Booth, to play Aunt Cissy. Things would have been fine if this hadn't prompted a rewrite ( not at Shirley Booth's request ) to enable Miss Booth to show off more of her delightful and unique persona. This unbalanced the show, which twenty years earlier wouldn't have been a problem, but the Rodgers and Hammerstein revolution of the completely integrated musical ( each of the elements - cast, scenario, songs, dancing - serving the whole ) had spoiled critics if not audiences. "A Tree Grows in Brooklyn" wasn't a glaring critical failure as a musical. I'd call it a modest unsuccess with a lot of great songs and a peerless star. One of the songs written for Shirley Booth, "He Had Refinement," is one of the funniest and cleverest songs in Broadway history.

I never knew anything about this book before, just the name. Definitely planning to read it in the coming year.