Undoing the Damage We Do Each Other

Persistent Love, Determined Hope: Reviewing ‘Cry, the Beloved Country’ by Alan Paton

Calamitous news comes at varying speeds. For some, as in the story of the patriarch Job, it strikes like a storm. Four harbingers of grief successively arrive and inform Job his livestock has been stolen or killed, his servants slain, his children flattened in a falling building. While one messenger still talks, the next arrives, until their staccato delivery of disaster is through.

For others, the woes creep out one at a time. Miseries pile up as one ravaging revelation lumbers slowly to the next. Such is the story of Anglican Zulu priest Stephen Kumalo in Alan Paton’s classic novel of South Africa, Cry, the Beloved Country.

When a letter arrives at his village church, Kumalo learns his sister is in trouble in Johannesburg. Gertrude first traveled to Johannesburg to locate her husband, gone missing amid its twisting streets and peripheral boroughs.

Kumalo has had no word from his sister since she arrived. Nor has he heard from his own son, Absalom, who went to look for Gertrude. Nor, for that matter, has he heard much from his brother, John, who relocated there many years before. The country’s biggest city seems to swallow alive any who enter.

Now that he has definitive news of his sister, Kumalo determines to go help her. He leaves his parish and travels to the city. Upon arriving, he’s immediately snookered out of money by a con artist. Not until he locates the man who sent the letter, another Anglican priest named Theophilus Msimangu, does he gain any sort of footing in the strange and dangerous place.

If Kumalo is Dante descending into the Inferno, then Msimangu plays his Virgil. And as the revelations of the netherworld shock and dishearten Dante, so the disclosures greeting Kumalo darken at every turn. His sister survives by prostitution and runs a brew house. She has a son, but the boy has no father. Kumalo’s own brother has abandoned both his Christian faith and his wife and taken up with political activists against the South African government. And the most brutal revelation of all: Absalom, working an ill-planned, botched robbery with his cousin, John’s son Matthew, has killed a white man in his home. Everyone is looking for the fugitive, not least his own father.

Compounding the grief and impossibility of the situation, the man Absalom kills, Arthur Jarvis, is someone diligently working for the equality and freedom of South Africa’s black citizens, a good guy who leaves behind manifestos testifying to his zeal and commitment to the cause—along with a wife and two kids, a girl and a boy. Of course this string of disasters isn’t quite finished; it turns out the victim’s father, James, is a neighbor of Kumalo, a rancher who lives on land near his parish.

What’s the path out of such a mess? How is it possible to undo the damage done by and to all these people, including the populace of the entire country whose black citizens live amid segregation, suffering, and oppression—conditions about to worsen?

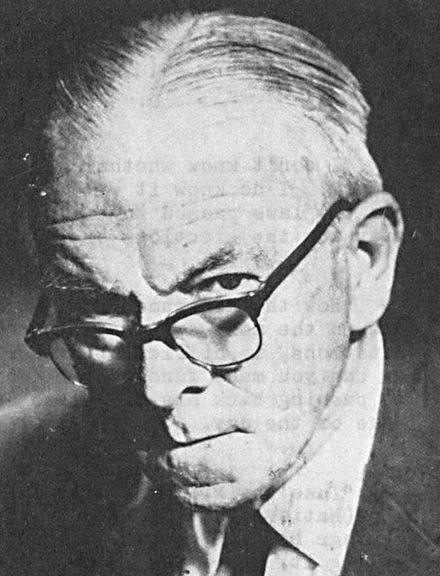

Paton was born in 1903 in South Africa. His faith drove his longstanding interest in racial justice and reconciliation. Raised a Methodist in a strict household, he veered toward Anglicanism in his twenties, eventually joining the fold in 1930. By then Paton was working as a teacher. In 1935 he was appointed the head of reformatory for young, black prisoners and began instituting liberal reforms including home visitations and open dormitories.

While touring Europe and North America in 1946, learning about prison-reform efforts, Paton began writing Cry, the Beloved Country. He began the book in Trondheim, Norway, and finished in San Francisco. It was published two years later in 1948. The policy of apartheid officially began that same year.

An activist at heart, Paton felt pushed in to politics. He became a founding member of the anti-apartheid Liberal Party in 1953, over which he presided from 1955 until the South African government outlawed multiracial parties in 1968. He regularly inveighed against apartheid, including while traveling abroad.

In 1960, he was granted the annual Freedom Award for his activism by the anti-totalitarian American organization Freedom House, an honor mentioned by the New York Times. As backhanded validation, the South African government seized his passport when he returned and denied him exit for a decade. Despite such setbacks, Paton soldiered on, writing all the while.

“I could have made better use of my life,” he once said, “but I did try hard to do one thing. That was to persuade white South Africa to share its power, for reasons of justice and survival.” As he said this there seemed little chance of prevailing. “In a country like South Africa,” he said, “there are many things that must be undertaken without any hope that the ventures will be successful, and there are many ventures in which one must persevere in spite of this lack of success.”

Of course Paton did ultimately succeed. It was the concerted, self-sacrificial struggle of South Africa’s black and white citizens against apartheid, along with pressure from the wider world, that eventually brought an end to the authoritarian regime. Paton died in 1988. Six years later, South Africa had a black president.

Paton wrote more than twenty books in all, some quite successful. But none captured the public’s imagination like Cry, the Beloved Country. By the time of his death, it had sold over 15 million copies.

He wrote the book to soften white society to the plight of their black neighbors. Any success that direction was paved by the towering figure of Kumalo. He is, as I mentioned, like Dante. He is also like Christ; having descended into Johannesburg to retrieve the lost, he later ascends up a forbidding hill to endure the agony of his son’s execution. But he is also like us all: crushed by cares and the burdens of an unjust, fractured planet.

Yet even in his trials Kumalo experiences grace that validates his love and buoys his hope. He befriends the boy of the man his own boy murdered. And the father of the victim, who could never understand his son’s advocacy for native Africans, adopts his his mission. He meets Kumalo in their mutual suffering, as reconciliation forms the only path out of the pain.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country is the sixth book in my 2023 classic novel goal. If you want to read more about that project, you can find that here and here. So far, I’ve reviewed:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (January)

Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (February)

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (March)

Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (April)

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (May)

In July, I’ll be reading and reviewing book one of Sigrid Undset’s historical Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy, The Wreath.

I read this book for the first time last year and was floored by it. I didn’t know much about Alan Patton, so I appreciated your background information. He lived a life that feels very Tolkien-that there are some tasks you must undertake regardless of the potential for success and failure, because it is right and just to do so, and it is what you have been called to.

I've always intended to read this book. This has whetted my appetite again. Thank you for an excellent review.