Daughter and Bride: The Story of Kristin Lavransdatter

Inside a Medieval World: Reviewing Nobel Laureate Sigrid Undset’s Classic Trilogy

“In skillful hands, the novel can give us greater insight into history than history itself does,” says writer Joseph Epstein in The Novel, Who Needs It? “One could, for example, put together a list of novels that would tell more about the history and psychological condition of the United States than a general history of the subject.”

Replace “United States” with “Medieval Norway” and Epstein’s line inevitably leads to a discussion of Kristin Lavransdatter, a trio of historical novels now a century old. So skillful were author Sigrid Undset’s hands she won the Nobel for literature in 1928 “principally for her powerful descriptions of Northern life during the Middle Ages,” and the three books in the Lavransdatter series—The Wreath, The Wife, and The Cross—anchored the committee’s judgement.

When I chose the titles for my 2023 classic novel goal I wanted a broad mix of male and female authors from different times and places. I’d heard great things about Kristin Lavransdatter. That would fit the bill. But the length! Taken together the trilogy exceeds eleven hundred pages. Maybe I could just read the first novel?

Nope. Once I finished The Wreath a few weeks ago I realized I’d be in for the duration. I couldn’t stop.

Undset grew up in a home steeped in antiquity. Her father was an archeologist and university lecturer, her mother an illustrator. The pair worked together until his premature death in 1893. Sigrid, one of three daughters, was just eleven at the time.

Financial straits placed university education out of reach, and at just sixteen Undset trained as a secretary and went to work for the German Electric Company in Oslo. She served there over the next decade but wanted something more; she saw herself as an artist and began writing novels on the side.

Undset began with medieval tales but, according to writer Brad Leithauser, was discouraged from further endeavors by an influential editor. “Don’t attempt any more historical novels,” he said. “You have no talent for it. But you might try writing something modern. You never know.“

Undset did write something modern, a novel about a woman in an adulterous relationship. Marta Oulie sold well when it released in 1907, as did her followup stories. But Undset couldn’t resist the pull of the historical. After a short medieval project in 1909, she was determined to dive completely into Norway’s past. But first to Rome for an affair.

Winning a grant to study abroad, Undset traveled to the Eternal City and interrupted a temporary marriage. It’s unfair to call her a homewrecker, but the bond between Norwegian artist Anders Castus Svarstad and his wife was sundered and Undset married the captivating, maddening man. “Our marriage did not turn out a success,” she later wrote a friend; “he had a gift for making other people, and himself, unhappy, and to turn friends and admirers into enemies. . . .”

While her fraught marriage slowly disintegrated and while surrounded by children, Undset began work on Kristin Lavransdatter, published between 1920–1922. No surprise the entire enterprise turns on marriage difficulties.

The first book in the trilogy, The Wreath, is set in early fourteenth century Norway and follows Kristin from her childhood until her marriage. Headstrong from the beginning and dotted on by her daddy, Lavrans Bjørgulfsson, Kristin is determined to marry for love. The man her father has selected for her, Simon Darre, is perfect—except Kristin feels no affection for him.

More problematic, while visiting a convent to suss out her feelings, she falls for a man who rescues her along the roadside, Erlend Nikulaussøn, a ravishing rake—noble and rich but living under a cloud with a mistress, two children, and a ban of excommunication. Kristin gives herself to her seducer before she knows the details but feels helpless once bound to him.

Then, after finagling her way out of her betrothal to Simon, she enlists her jilted suitor in a coverup of the affair, trying to prevent the worst of it from hurting her father, who she loves as much as he cherishes her.

I came to the story cold, and as it unfurled page by page The Wreath struck me as a fairly conventional romance—not a genre I tend to read. What did I think of it? I wasn’t quite sure how I was going to review it. Was there enough here? But then I hit the end, where a complication flies into view so momentous I realized I had to read on. Perhaps my take would emerge as I read more of the story. I was hooked.

There are plenty of complications in the first novel, but most revolve around Kristin wanting Erlend and her fears of being thwarted. By the time we hit Book 2, The Wife, the complications spin out in a thousand variations. Everything falls apart.

If Book 1 was a coming-of-age story, Book 2 is a killing-of-dreams story. Kristin and Erlend possess an undeniably powerful bond, but their life begins to unravel in ways small and big. Her headstrong attitude can turn to pettiness and meanness with her husband; his willfulness in love turn to weakness and aloofness in other endeavors. Rifts and chinks begin to show.

One thing Undset’s readers universally mention about her work? The plausibility of the world she conjures. We may be seven hundred years removed from the action, but her intimate knowledge of the period pulls us in like spectators standing just an arm’s length from the drama. These people and their lives feel palpably real: We all know people in similar relationships and might have been in one ourselves.

Of course, it’s not all bad. As Kristin moves into what we could call middle age, she experiences many satisfying and positive turns along with all the negative twists and ruts. The bond between Kristin and her parents, damaged by her lies, mends. Remarkably, a friendship forms between Erlend and his betrayed father-in-law Lavrans. Erlend even begins to redeem himself for Simon, who has since married Kristin’s little sister. The rivals are now brothers—and none too soon.

Erlend, a military commander in the king’s service, plays politics and finds himself embroiled in a scheme that claims all his property and nearly his life. Simon steps in and negotiates his release from the king’s tower where Erlend has been tortured to reveal the names of his conspirators. Through it all, Kristin’s desperate love for Erlend deepens, despite the peril into which he plunged himself and his family.

Go back to Joseph Epstein’s point: The daily life of medieval gentry and peasantry, farmers and monks, swordsmen and pilgrims, housewives and nuns sets the stage for all this drama. H. L. Mencken once joked that historians were failed novelists, but Sigrid Undset was a successful historian. Footnotable features of medieval life—everything from food, farming, and hunting, to medical remedies, church law, and superstitions—create the breathable atmosphere of Undset’s world.

But it’s more than history. Through all their difficulties, Undset’s characters reveal their interior lives—not just the history of the period but, as Epstein says, the “psychological condition” of the time. That means in part an inescapable religiosity. The struggle of Kristin and Erlend’s marriage is not simply the clash of personalities; it’s also an awareness of their sins and betrayals, their pride and bitterness, and how those moral and spiritual failings shape their behavior toward themselves and others.

They are not like us, and yet we are them.

For modern, secular readers the religious dimension of the novels might feel as foreign as the rest of the era. Time bends around the church calendar, characters keep the alternating fasts and feasts of the seasons, and they attend mass, confess their faults, consult with monastics, and deal with the judgement of the bishop in matters like adultery.

Kristin’s married life begins in sexual scandal and ends there as well. In Book 3, The Cross, Kristin and Erlend’s union finally ruptures—or nearly so. Estranged, the two nonetheless meet again and conceive a child. But Erlend refuses to rejoin her at their home through the pregnancy or birth of their son. He instead waits for her at a small ancestral holding to which he has retreated and to which she refuses to return.

When the husbandless Kristin is accused of adultery by the community, Erlend comes to her defense, but a fracas turns fatal and he succumbs to his wounds. The widowed Kristin then becomes another sort of bride. After undertaking a pilgrimage she joins the cloister.

She knelt during the high mass, when the archbishop himself performed the service before the main altar. Clouds of frankincense billowed through the intoning church, where the radiance of colored sunlight mingled with the glow of candles; the fresh, pungent scent of incense seeped over everyone, blunting the smell of poverty and illness. Her heart burst with a feeling of oneness with these destitute and suffering people, among whom God had placed her; she prayed in a surge of sisterly tenderness for all those who were poor as she was and who suffered as she herself had suffered.

And then she says, quoting the Prodigal Son, “I will rise up and go home to my Father.” It’s there at the convent where Kristin faces her final challenge, a heroic act of selfless love in the midst of the Black Death, which ultimately claims her life.

Love and loss, hazards and hopes, desire and death: It’s all there in those thousand-plus pages. Kristin’s life starts small, swells with her growing family, and recedes again as misfortune pares it all back to the one thing she has left to offer, the sacrifice of herself.

Turns out Undset had a talent for historical fiction after all.

Readers resonated with Kristin Lavransdatter from the first. Not only did the Nobel committee take notice and extend their coveted prize, but publishers around the world began translating and releasing editions in local markets. At the time of the prize Undset had already sold a quarter million copies in Germany.

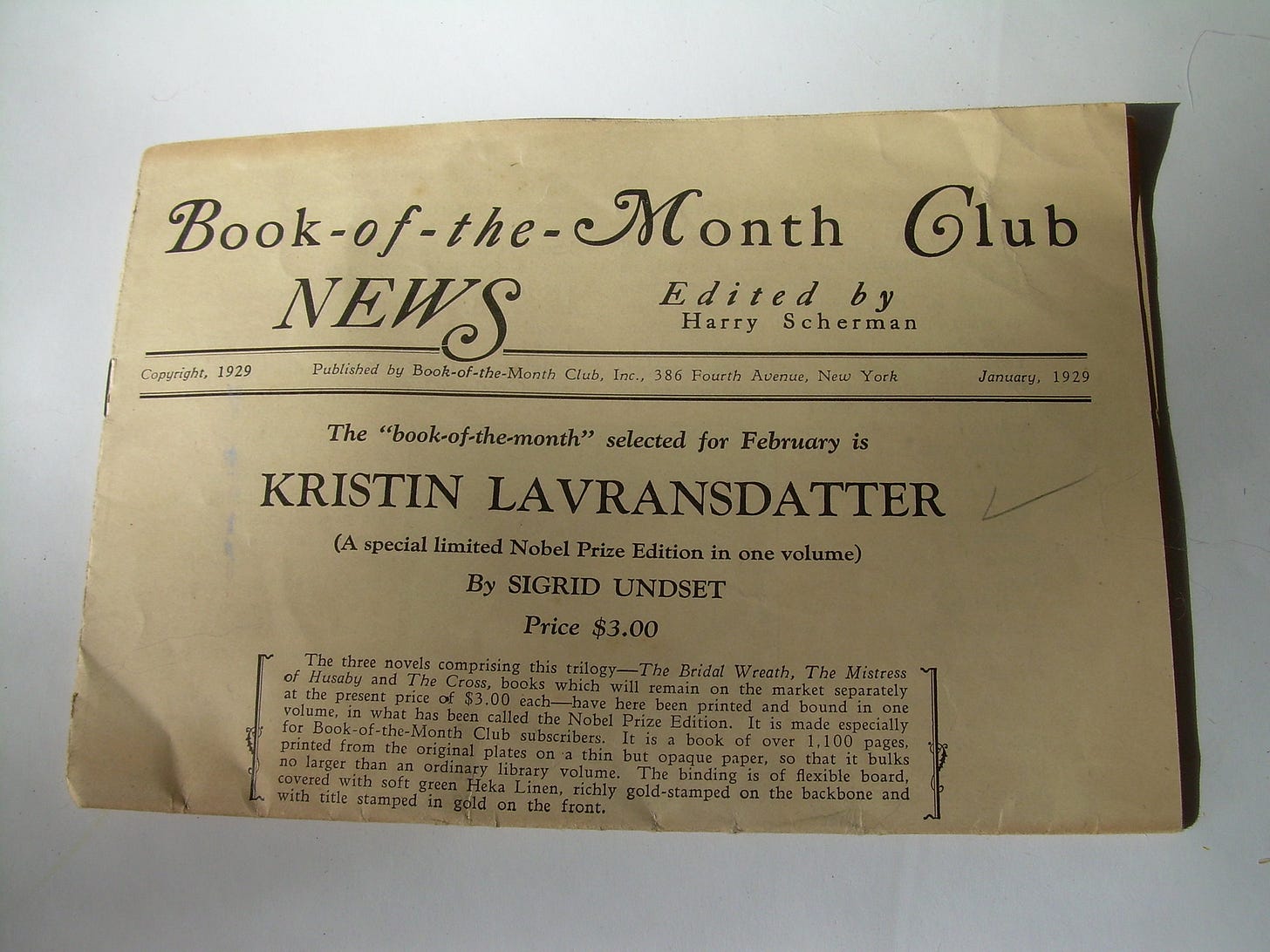

A year after the prize, the Book-of-the-Month Club in America selected a special three-in-one volume of Kristin Lavransdatter for its hundreds of thousands of members. Almost a century later a similar edition in Tiina Nunnally’s modern translation is available from Penguin. At this point, it’s found its way into eighty other languages as well.

“If you peel away the layer of ideas and conceptions that are particular to your own time period,” Undset once said, “then you can step right into the Middle Ages and see life from the medieval point of view—and it will coincide with your own view.”

In Sigrid Undset’s skillful hands, it’s impossible to imagine any other outcome.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends. And please hit the 🔄 below to restack it.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy is the seventh book in my 2023 classic novel goal (I know it’s three, but we’ll count it as one). If you want to read more about that project, you can find that here and here. So far, I’ve reviewed:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (January)

Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (February)

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (March)

Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (April)

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (May)

Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (June)

In August, I’ll be reading and reviewing Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

It's really satisfying to hear you say that the "entire enterprise turns on marriage difficulties"--I once described the trilogy as "about marriage" at an extended family dinner, only to be told that the scope of Undset's work was so much deeper than that (rigorous historical research that reveals the tensions between Christianity and Nordic myth in medieval Norway and whatnot...)

Don't see why it can't be both.

It's the best book about marriage I've ever read.

The review is steeped in the love of literature so carries that dimension too. Catnip! I certainly want to read The Story of Kristin Lavransdatter. Reading the review I was continually drawn back to Laurus, another historical novel with religious currents set in the Medieval period. That alone makes me want to read it.