How Stories Work, Especially the Spooky Ones

Henry James, Ghost Writer: Reviewing ‘The Turn of the Screw’

As I assembled the books I would read month by month for my classic novel goal this year, I knew I wanted something spooky for October. I’m not much for horror or the macabre, so I didn’t really know where to start. I asked around, and a friend recommended The Turn of the Screw by Henry James.

“It’s perfect,” she said. “You’ll love it.”

Did I?

There’s something necessarily disorienting about classic fiction, especially the further back you go. When, for instance, we read Jane Austen’s delightful Pride and Prejudice, we’re asked to inhabit a world vastly different than our own with strange conventions and assumptions. “The past is a foreign country,” as L.P. Hartley says, opening The Go-Between: “they do things differently there.”

To one degree or another, this was true for all the classic novels I’ve read so far this year. Each one pulls contemporary readers out of the moment and asks them to entertain life unlike our own; this is one of the virtues of reading, broadly speaking. But of all the novels I’ve read for this project, the one most alien—and alienating—was The Turn of the Screw, first published in 1898.

Written at the end of the nineteenth century and set a generation or so before, the story concerns an unnamed governess tasked with overseeing two preadolescent orphans. Flora and Miles’s parents have died and their rich uncle wants little to do with them; so, he sets them up in his massive, mostly empty country estate with a small staff to see to their needs.

Above all, he wants not to be bothered with them. The governess is given carte blanche in their upbringing. And she’s thrilled because the children seem perfect—the most beautiful, innocent creatures she’s ever encountered. Of course, not all is as it seems.

The first inkling? Miles has been expelled from school. Problematically, the reason is unclear from the headmaster’s letter. More problematically, the governess hesitates in asking the child. So begins a feature of the novel calculated to frustrate the reader’s penetration of the story.

The Turn of the Screw is a study in ambiguity with characters talking around, beside, over, beneath, and generally at any angle but directly about the subject at hand. This proves especially tricky when the subject includes a pair of ghosts.

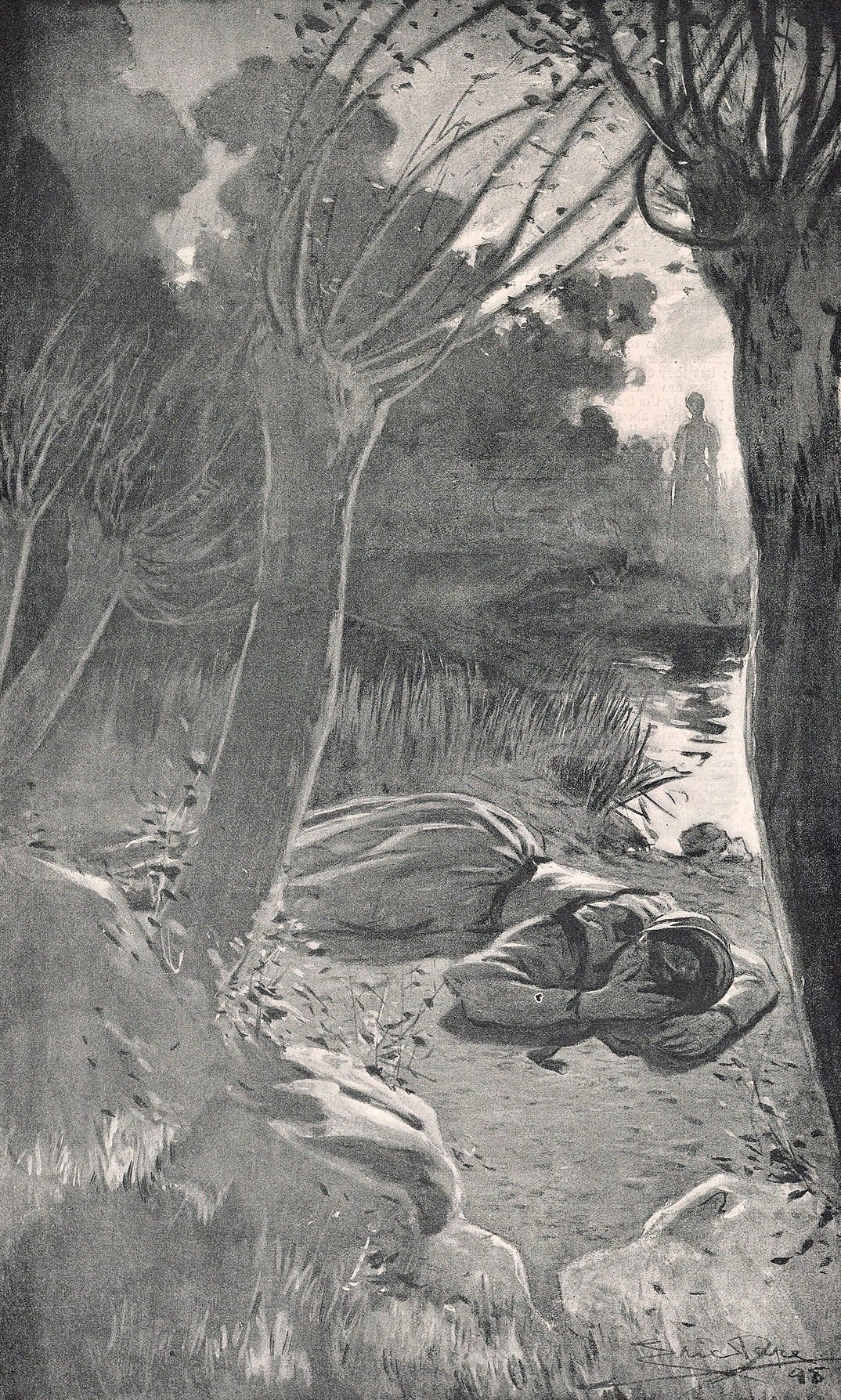

The governess encounters the male ghost first, then the female. After talking with housekeeper Mrs. Grose, she identifies them as Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, the uncle’s former valet and the children’s prior governess. Quint and Jessel carried on an entanglement that resulted in her ruin, after which Quint stumbled drunk from a pub house and died one night on an icy road. And now? Why are they hanging about?

The governess is convinced the ectoplasmic couple is intent on corrupting the children. Quint had always been a corrupting influence, according to Mrs. Grose. Worse, the governess believes they’re already partway toward their frightening goal: One night Miles sneaks out to converse with Quint; another time Flora runs off to be with Jessel.

But do they?

Based on the testimony of the other characters, no one else actually sees these ghosts except the governess. At least, it’s not clear they do. James’s roundabout narration and his characters’ reticent dialog keep us guessing about what’s actually happening and who really sees and knows what. The governess can’t ask a straight question, and no one else can provide a straight answer.

As the story builds towards its climax, the governess’s obsession with the ghosts drives Flora away. Mrs. Grose takes her to be with her uncle, while the governess and Miles stay to have it out with Quint. Miles finally admits to his wrongdoing at school, after which Quint appears—or does he?—and brings the story to its fateful, tragic close.

Readers lapped it up, which was good news for James. He needed a hit. After the initial popularity of novels such as Daisy Miller (1878) and The Portrait of a Lady (1881), he’d written a string of unsuccessful plays and found himself in a bit of a slump. The Turn of the Screw gripped audiences from the start, reading bit by bit as it was serialized in the pages of Collier’s Weekly.

Published in book form later in 1898, the story has captivated readers ever since—in large part because no one can agree on what the story is about, what it means, or even what happens. Hence its overriding alienating quality.

But there’s something alluring in the elusive, isn’t there? It’s a powerful reminder of what a book is capable of. More than relate events or ideas, a narrative creates an experience for the reader. By withholding clarity, even resolution, James invites a sort of restless engagement that amplifies the tension like . . . the turn of the screw.

Did I love it? No. Will I read it again? Most definitely. I still want to know what happens.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw is the tenth book in my 2023 classic novel goal. If you want to read more about that project, you can find that here and here. So far, I’ve read and reviewed:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (January)

Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (February)

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (March)

Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (April)

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (May)

Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (June)

Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy (July)

Zora Neale Hurston’s The Eyes Were Watching God (August)

Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (September)

I also snuck in a couple bonus classic novel reviews: John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

In November, I’ll be reading and reviewing Shūsaku Endō’s Silence.

I bought this, knowing you were going to review it. I have read quite a lot of classic literature, so I'm used to the flowery, old-fashioned writing style. But this...THIS...I struggled so hard with! The writing style was so long-winded and comma-filled, oh my goodness. The story kept bobbing up and down between the waves of his prose. The interesting bits pulled me through it and I'm glad I had the experience, but boy... I drowning there for a bit, hahah!

James’s language is challenging. If he can find a roundabout and complicated way to write a sentence, you can be sure he’ll do it. All that aside, the story carried me, increasingly so toward the end, which I had to re-read twice and then ponder.