First Draft, Last Draft: How Hemingway Became Hemingway

Reviewing the Celebrated Novelist’s Classic Memoir, ‘A Moveable Feast’

Near the end of his life, Ernest Hemingway cracked open a time capsule from its beginning. In 1928 he left two small steamer trunks in storage at the Ritz Hotel in Paris. He never retrieved them. Almost thirty years later in 1956 hotel staff asked him if he might finally take them off their hands. He did—and uncorked the past as he opened the lids.

Old clothes waited within, along with newspaper clippings, books, pages of stories, and notes on his debut novel The Sun Also Rises. Also inside? Memories of those gestational years in Paris, beginning in 1921, where he developed as a writer, matured as man, and made fateful decisions that shaped his future.

Hemingway had considered writing about the period before, but receipt of the trunks provided the impetus he needed to begin what he called his “Paris Sketches.” He started in 1957 but never quite finished before his suicide in 1961.

Helped by editors at Scribner’s, Hemingway’s widow Mary prepared the final manuscript and published the book under the title A Moveable Feast in 1964, leaving out several sketches. You can read those in the restored edition of Hemingway’s classic memoir, prepared by his grandson Sean Hemingway, published forty-five years later in 2009. As the label suggests, the new edition is in some ways older than the original, containing many emendations and supplements that make whole the work as Hemingway left it—at least as Sean Hemingway understood the archival materials.

Of course, if you’re looking for an understanding of the experiences and relationships that shaped Hemingway’s life and work, either edition will do. As I read, I was particularly interested in three facets of that work: his methods, his relationships, and their interplay.

Methods

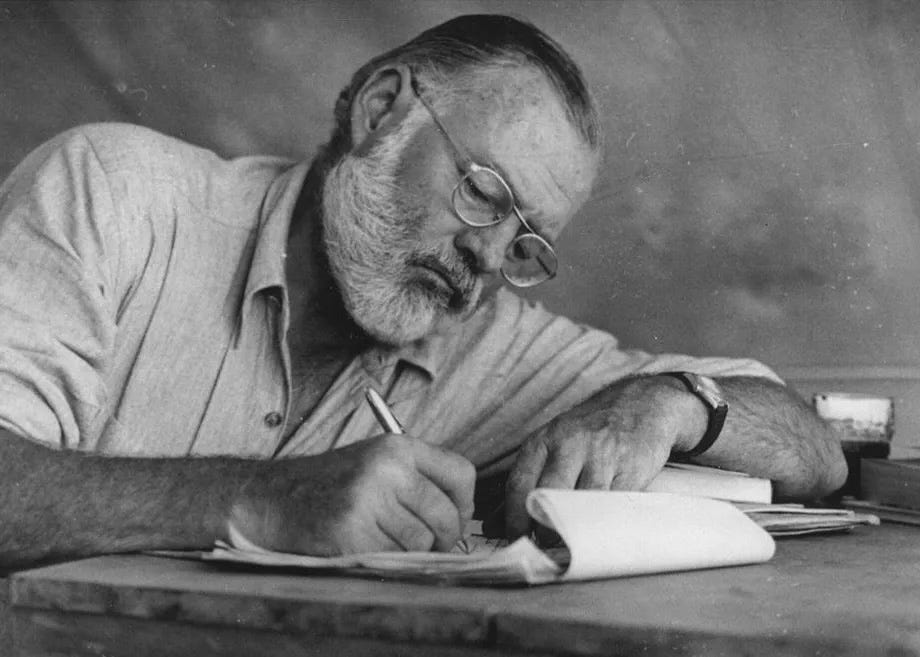

The memoir begins in a Paris cafe with Hemingway doing what he did most days, writing a story, scribbling away in a notebook with a pencil and just enough coffee and then rum to keep the words flowing. For a stretch the work proves easy. “The story was writing itself and I was having a hard time keeping up with it,” he says.

The further into the story he travels, however, the more like work it becomes. The energy changes: “I was writing it now and it was not writing itself and I did not look up nor know anything about the time nor think where I was nor order any more rum. . . .”

Upon finishing, he closes his notebook. “I was very tired,” he says. He orders a dozen oysters and a half-carafe of wine and reflects:

After writing a story I was always empty and both sad and happy, as though I had made love, and I was sure this was a very good story although I would not know truly how good until I read it over the next day.

The episode reveals aspects of his process that also come out elsewhere in his repeated mentions of stopping and starting work. Hemingway compartmentalized his writing. While he would, for instance, read over this story the following day, he wouldn’t think about it in the meantime. Instead, he ordered dinner to clear his mind. He might also read books or gamble on horses, the winnings of which he hoped could supplement his small earnings.

He never exhausted the work; he saved something for later. “I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next,” he explained. “That way I could be sure of going on the next day.” It’s a curious tension: He would finish the day by leaving something hanging but then intentionally distract himself from thinking about it. “That way,” he said,

my subconscious would be working on it and at the same time I would be listening to other people and noticing everything, I hoped; learning, I hoped; and I would read so that I would not think about my work and make myself impotent to do it.

Elsewhere he says, “When I was writing, it was necessary for me to read [books] after I had written, to keep my mind from going on with the story I was working on.”

In several passages about writing he mentions other peculiarities of his approach, writing, for example, sentences unadorned by “scrollwork and ornament,” but also

carrying a rabbit’s foot for luck when writing;

never reading unfinished work aloud (“much more dangerous . . . than glacier skiing unroped before the full winter snowfall has set over the crevices”); and

only writing about certain subjects in French because the associated vocabulary employed French terms.

Hemingway liked showing up at a cafe shortly after opening and beginning work in with the morning smells and quiet. If someone who knew him came through the doors and spoke, however, he was done for. “Your luck had run out and you shut the notebook,” he said, addressing such a crisis in the second person. “This was the worst thing that could happen.” From the rest of the memoir, it seems as though these interruptions would have been a common occurrence. After all, Hemingway knew a lot of people.

Relationships

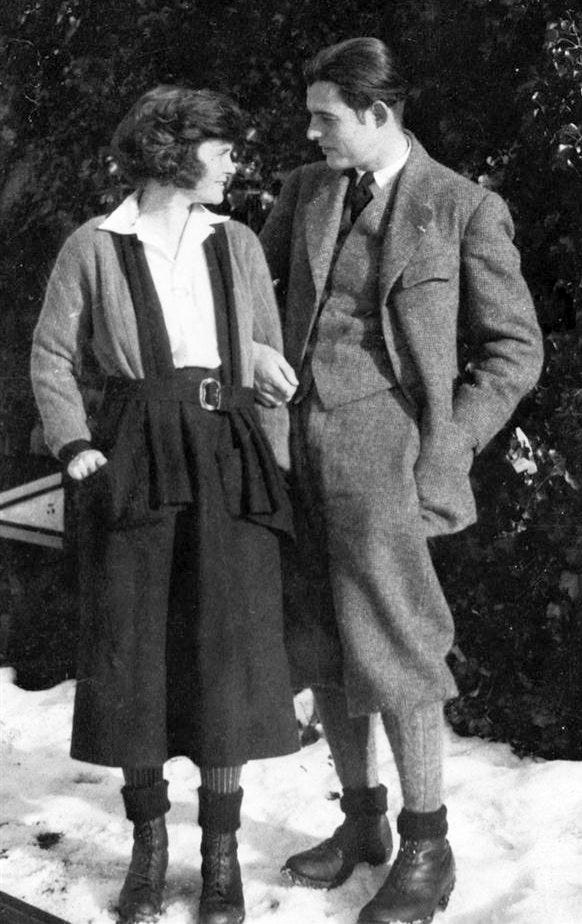

Hemingway’s narrative is populated by an array of people of varying levels of intimacy. Though eight years his senior, Hemingway’s first wife Hadley captivated him early on, and the relationship forms a foundational bond in the narrative. While he offers little in the way of an arc to the story, their marriage also creates the beginning and end of this chapter in his life, which closes because of his infidelity. They divorced in 1927, and though writing about the event three decades later his regret is palpable.

It’s safe to say Hemingway’s life as an author would have taken much different shape without her. The couple moved to Paris on his pay as a reporter shortly after marrying. But Hemingway, networking with writers while there, wanted nothing more than to focus exclusively on fiction. Though money was extremely tight, Hadley encouraged him to do so. She gets a few great lines in the book, too, including: “There are many sorts of hunger. . . . Memory is a hunger.”

The two endured hunger of a real sort on Hemingway’s reduced pay, but appetites of all sorts form a theme in his relationships. For instance, Hemingway portrays F. Scott Fitzgerald as consumed by his alcoholism, but his friend possessed destructive appetites of many kinds—not least his fixation on pleasing his jealous, manipulative, and mentally unstable wife, Zelda, who in Hemingway’s telling actively undermined her husband’s work and prevented him from writing.

Fitzgerald gets more “screen time” than most anyone in the book, and a few of the episodes and escapades are truly amusing—such as when he and Hemingway head out of town to retrieve a car, the zany roadtrip spoiled by Fitzgerald’s many unchecked personal quirks, including hypochondria, dipsomania, and general flakiness.

But Hemingway is gracious with his friends’ faults, Fitzgerald’s and others’. He seems free with blunt characterizations and yet still softens the blow—in most instances. The only person who comes in for unreserved insult is Ford Madox Ford, for whom Hemingway guest edited an issue of Ford’s literary journal Transatlantic Review.

Describing a moment Ford interrupted his evening at a sidewalk cafe:

I had always avoided looking at Ford when I could and I always held my breath when I was near him in a closed room, but this was the open air and the fallen leaves blew along the sidewalks from my side of the table past his, so I took a good look at him, repented, and looked across the boulevard.

It’s just a glimpse of a thoroughly unflattering portrait.

Hemingway is far more gentle with Gertrude Stein, who served as something of a mentor and with whom he later had a falling out. He seems to have tried to like Wyndham Lewis for the sake of his friend Ezra Pound, but couldn’t resist a few zingers, including comparing his eyes to those of “an unsuccessful rapist.”

Pound escapes unscathed, as does the gracious Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company and who loaned Hemingway books when he was hard up for cash. It’s worth adding how important that was considering his need for reading material while he was writing (“it was necessary for me to read after I had written”).

How did Hemingway become Hemingway? Writing all those years after the events he describes, he never says it; but you can see it.

Interplay

We develop as individuals in relation to others, defining ourselves by degrees of distance to their ideas, loves, commitments, and more. Working amid Lost Generation expat writers in Paris, and younger than most if not all of them, Hemingway was learning to be himself. He listened to his elders, people like Stein and Pound, and he developed his own opinions in reaction to theirs. His values took shape as he witnessed and experienced life created by theirs.

For instance, Hemingway criticized Fitzgerald for writing magazine short stories instead of buckling down to write a serious novel. He considered it “whoring.” Hemingway praised The Great Gatsby and was annoyed his friend couldn’t get back to what he considered real work. “If he could write a book as fine as The Great Gatsby,” he said, “I was sure that he could write an even better one.” But what did he know of it?

Hemingway had only written one novel then, the manuscript which was stolen and which he didn’t consider very good; he counted it a blessing the book was lost. It wasn’t until the end of this period that he wrote his debut novel, The Sun Also Rises. I take his criticism of Fitzgerald to be a mix of personal aspiration and vicarious disappointment: If I could write a novel like that, I wouldn’t be messing around with short stories. Hemingway also took close note of Fitzgerald’s vices—for instance, booze—because he was prone to the same and could see how they interfered with staying productive.

That is to say, Hemingway became Hemingway amid complicated friendships, small jealousies, and creative rivalries. Gertrude Stein was, on the one hand, a mentor; he desired her approval. But as Hemingway developed his own artistic vision, and as it markedly diverged from Stein’s, their relationship cooled. He wanted what Stein could offer as a literary gatekeeper; he didn’t want to be her acolyte.

Hemingway discovered his artistic identity within a dynamic environment full of camaraderie, admiration, encouragement, competitiveness, and, in the case of figures like Ford and Lewis, scorn. Though he possessed his own creative vision, his talent and ambition would not have flourished or taken the shape they did without the influence of this complex social landscape.

A Moveable Feast was the ninth book in my classic memoir goal for 2024. Here’s what I’ve reviewed so far and what’s in store for the rest of the year:

January: Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

February: Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

March: Richard Wright, Black Boy

April: Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

May: Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland

June: John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

July: Stephen King, On Writing

August: Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

September: Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

October: John Stuart Mill, Autobiography

November: C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

December: Beryl Markham, West with the Night

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Before you go . . .

Wonderful! I’ve never quite forgiven Hemingway for that last scene in A Farewell to Arms, but this essay helps.

Fittingly timed, since Hemingway's 125th birthday was earlier this year. Thanks for the write-up.