Liberation Narratives: Out from Slavery

Exemplars of Pioneering Texts: Frederick Douglass’s ‘Narrative’ and Harriet Jacobs’s ‘Incidents’

Americans have pioneered much the world enjoys: jazz, blue jeans, the lightbulb, airplanes, basketball. And, though non-American precedents exist, because of the peculiar fact of our peculiar institution we’ve also led the way in the literary genre known as the slave narrative.

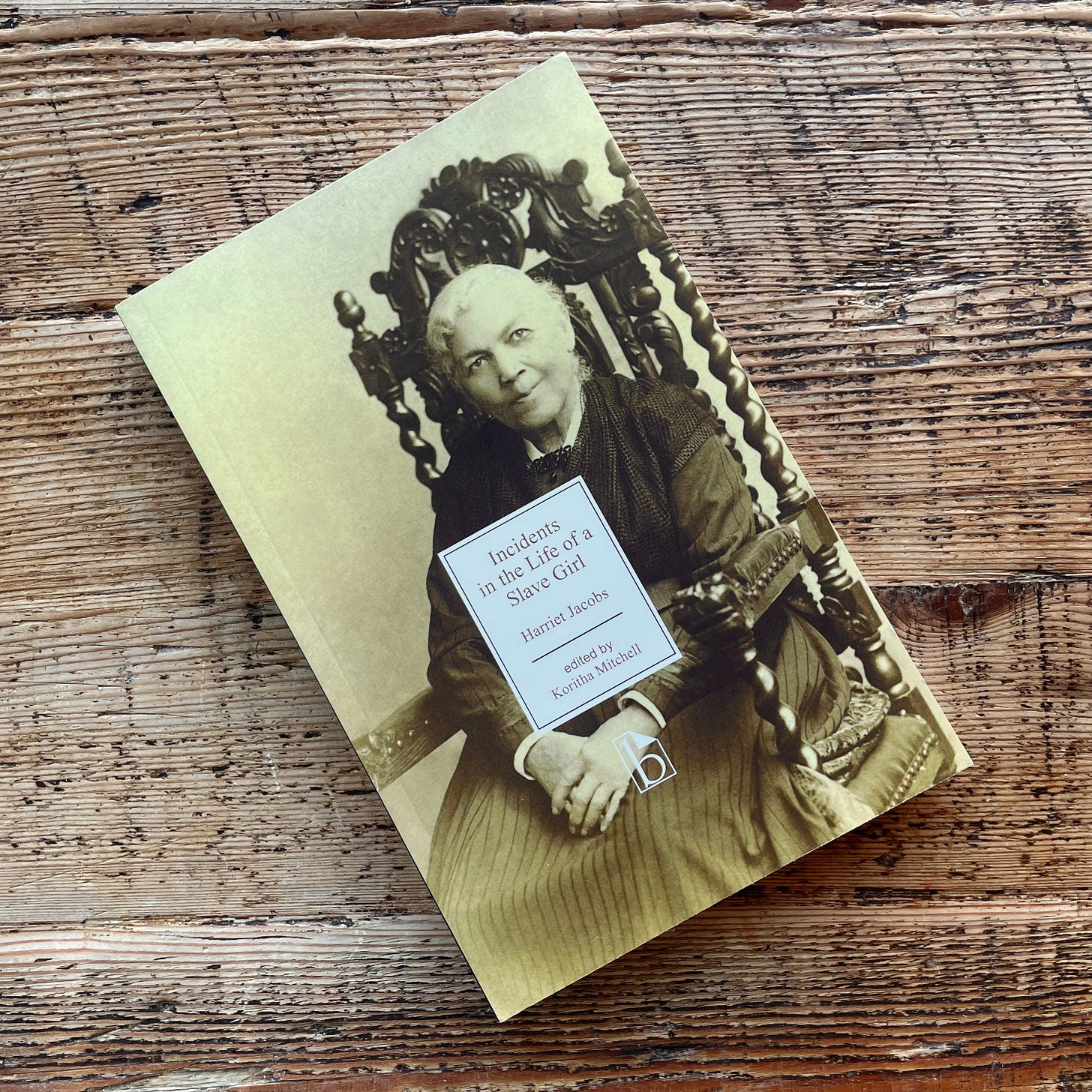

I recently read two exemplars of the form, Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. But, having done so, I’d like to float an objection: I think the genre is misnamed. These aren’t slave narratives; they’re liberation tales.

I decided to read both Douglass and Jacobs after asking author Gregg Hecimovich what books written before the modern era by black American authors he would recommend to better understand both their world and our own. The pair formed his first two suggestions and, having now read them, I can see why.

Both accounts paint a portrait of life once experienced by the vast majority of black Americans, characterized by enslavement, violence, and deprivation. They also reveal the special resilience, fortitude, and daring that marked the lives of many in spite of the repressions they experienced on a daily, even hourly, basis.

Visitations of Violence

Douglass published his narrative in 1845, beginning the story at his birth in 1818. He barely knew his mother. They were separated while he was still an infant, as was generally the practice; why, Douglass didn’t know but speculated it served to prevent children’s attachment to their mothers. His father? Likely his white master, though Douglass only knew so from rumors.

Violence came often. While Douglass was “quite a child” he witnessed his master scourge his Aunt Hester. Her crime? She’d been seeing a neighboring man against the master’s command. When the master found out, he was livid. “Had he been a man of pure morals himself, he might have been thought interested in protecting the innocence of my aunt,” said Douglass; “but those who knew him will not suspect him of any such virtue.”

He stripped the woman naked, tied her arms, and stood her upon a stool while he hooked her arms to the roof joist. “Her arms were stretched up at their full length, so that she stood upon the ends of her toes,” Douglass described the scene. “He then said to her, ‘Now, you d—d b—h [Douglass’s excision]. I’ll learn you how to disobey my orders!’ and after rolling up his sleeves, he commenced to lay on the heavy cowskin [whip], and soon the warm, red blood (amid heart-rending shrieks from her, and horrid oaths from him) came dripping to the floor.”

How does a mere child respond to such a scene? “I was so terrified and horror-stricken at the sight, that I hid myself in a closet, and dared not venture out till long after the bloody transaction was over. I expected it would be my turn next. It was all new to me.” Not any longer—though, fortunate for him, young Douglass’s situation soon changed for the better.

Hunted at Home

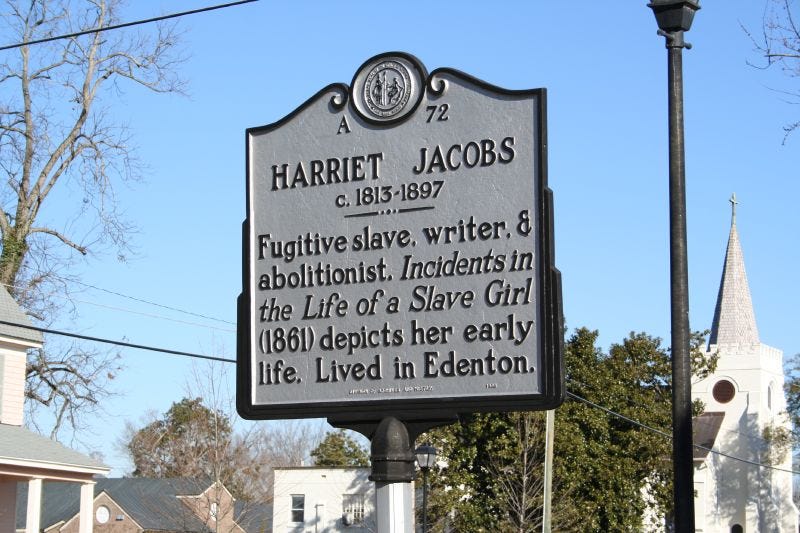

Like Douglass, Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in 1813, though she was unaware of her circumstances. “I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise,” she said in her memoir, published pseudonymously in 1861 just months before the outbreak of the Civil War. Domestic bliss ended when she was six and her mother died. Her protection was gone.

She discovered her true precarity upon hitting puberty, when she inadvertently began drawing the eye of her lascivious master. He started making lurid advances early on, as Jacobs tells it, shocking her young ears with solicitations scandalous enough she wouldn’t repeat them in print decades later as full-grown woman.

Underneath the nose of her mistress—though not beyond her suspicions—her master doggedly pursued her for years, attempting to either win her apparent consent or take full advantage of her powerlessness. Circumstances prevented him from having his way, but he never let up.

When Jacobs became pregnant by another white man—this relationship being consensual—she tried playing the angles against her master. To no avail. Eventually she brought two children into the world and worked to free not only them but herself.

Life of Servitude

As Douglass and Jacobs’s stories unfold, the inherent vulnerability and danger of their position proved constant, pressing, and palpable. The enslaved lived by the leave and whim of their supposed owners. Masters sundered relationships, selling family members; they physically threatened and acted on those threats; they deprived their “possessions” of anything they might consider their own—their time, their labor, or any increase from the investment of either.

As a young man, Douglass was farmed out to work for another master. He was later freed to work on his own in the shipyard but was required to remit his earnings to his master. Douglass worked alongside free men who pocketed the full sum of their wages, while he was forced to watch the fruit of his labor fatten the purse of man who did nothing to earn a penny and yet demanded an accounting right down to the penny.

“I was now getting one dollar and fifty cents per day,” said Douglass.

I contracted for it; I earned it; it was paid to me; it was rightfully my own; yet, upon each returning Saturday night, I was compelled to deliver every cent of that money to Master Hugh. And why? Not because he earned it,—not because he had any hand in earning it,—not because I owed it to him,—nor because he possessed the slightest shadow of a right to it; but solely because he had the power to compel me to give it up. The right of the grim-visaged pirate upon the high seas is exactly the same.

And masters could compel handing over much more. Though Jacobs bore her children, her master technically owned them and could hold their fate over her head to demand whatever he wanted of her. He could, after all, sell and send them away if she ever displeased him—a constant threat because he wanted the one thing she would never give him.

To Be Free

As both Douglass and Jacobs’s stories reveal, this sort of unchecked power over other humans not only degraded their own lives, it also corrupted the lives of those who exercised the power, amplifying the danger under which the enslaved lived. At some point, both realized they must escape to freedom.

For Douglass, it started early. His mistress taught him the rudiments of reading as a child before she was warned that literacy would ruin him as a slave. Too late. Douglass had a taste and mastered the skill by trading food for lessons from poor white children in his Baltimore neighborhood.

He had to read on the sly, but kept up the practice whenever he could. Eventually, he landed on a copy of The Colombian Orator which contained two passages that changed his life. “I found in it,” he said in a bit worth quoting at length,

a dialogue between a master and his slave. The slave was represented as having run away from his master three times. The dialogue represented the conversation which took place between them, when the slave was retaken the third time. In this dialogue, the whole argument in behalf of slavery was brought forward by the master, all of which was disposed of by the slave. The slave was made to say some very smart as well as impressive things in reply to his master—things which had the desired though unexpected effect; for the conversation resulted in the voluntary emancipation of the slave on the part of the master.

In the same book, I met with one of Sheridan’s mighty speeches on and in behalf of Catholic emancipation. These were choice documents to me. I read them over and over again with unabated interest. They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance. The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over the conscience of even a slaveholder. What I got from Sheridan was a bold denunciation of slavery, and a powerful vindication of human rights. The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery. . . . The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers.

The book gave Douglass the language he required to shape thoughts of his own freedom. It would take years before he could act decisively on that personal evolution, but he eventually did, escaping to the North, where his skill with words made him one of America’s greatest orators and advocates for human liberty.

Her Own Person

Jacobs was also taught to read by her mistress. She called it a “privilege, which so rarely falls to the lot of a slave.” At points her literacy prompted the consternation of whites. But reading also kept her sane during an extraordinary period in the slow adventure of her escape.

In a plot to free her children, Jacobs staged her flight north. But instead of actually going, she hid in a tiny, cramped cubby in her grandmother’s house. She hoped her flight would prompt her master to sell her children and thus allow her lover to buy them and secure their freedom when they came to market. But her master was too jealous and angry to take the bait, and Jacobs was forced to spend seven years(!) in her cubby. She could read by the light filtering through the chinks in the wall, but was otherwise more confined than ever.

Finally, her children found their freedom—though it was tenuous—and she hers. Opportunity to truly escape finally arrived and, through the kindness of many, Jacobs made her way north.

Jacobs also read abolitionist literature then. She reunited with her brother who had similarly escaped, and the two temporarily ran an anti-slavery reading room in Rochester, New York. But she was never safe. Jacobs’s master pursued her, using whatever means he could manage to have the fugitive returned. People attempted to purchase her freedom, but she recoiled. “The more my mind had become enlightened,” she said, “the more difficult it was for me to consider myself an article of property.”

At last, however, a transaction was negotiated on her behalf. “I was sold at last!” she said with mixed emotions.

A human being sold in the free city of New York! The bill of sale is on record, and future generations will learn from it that women were articles of traffic in New York, late in the nineteenth century of the Christian religion. It may hereafter prove a useful document to antiquaries, who are seeking to measure the progress of civilization in the United States. I well know the value of that bit of paper; but much as I love freedom, I do not like to look upon it. I am deeply grateful to the generous friend who procured it, but I despise the miscreant who demanded payment for what never rightfully belonged to him. . . .

Jacobs was free, finally recognized for what she always was: her own person.

From our vantage point in the twenty-first century, it’s hard to contemplate the realities described by such testimonies as Douglass and Jacobs’s. All the more reason to read them.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass was the second book in my classic memoir goal for 2024. Jacobs’s Incidents was a bonus read. Here’s what I’ve reviewed so far and what’s in store for the rest of the year:

January: Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

February: Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

March: Richard Wright, Black Boy

April: Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

May: Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland

June: John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

July: Stephen King, On Writing

August: Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

September: Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

October: John Stuart Mill, Autobiography

November: C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

December: Beryl Markham, West with the Night

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Hey Joel,

My interview with the Pulitzer winning biographer of Frederick Douglass:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHflpxDG-Ow&t=2540s

From what I understand, even under southern state chattel slavery laws Harriet Jacobs should never have been enslaved in the first place, as her grandmother had been freed and thus her descendants should have been free. Also, I'm not sure it could be said that Harriet's relationship was entirely consensual. As she describes, the only way she could see to counteract her master's advances was by accepting the advances of another powerful white man in the community, and the necessity of the relationship was clearly a source of grief and shame to her.