She Wrote Her Way to Freedom

The Mystery of America’s First Black Female Novelist: Reviewing ‘The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts’ by Gregg Hecimovich

When the celebrated African American science fiction author Octavia Butler first showed interest in the genre as a young woman, she saw none like herself in the novels she read. “I certainly wasn’t in the science fiction,” she told the New York Times in 2000. “The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway.” So what did she do?

“I wrote myself in,” she said, “since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing. I can write my own stories and I can write myself in.” More than 140 years before, an anonymous enslaved woman did something similar, only she wrote herself out—out of slavery. Furman University professor Gregg Hecimovich tells that remarkable story in The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts.

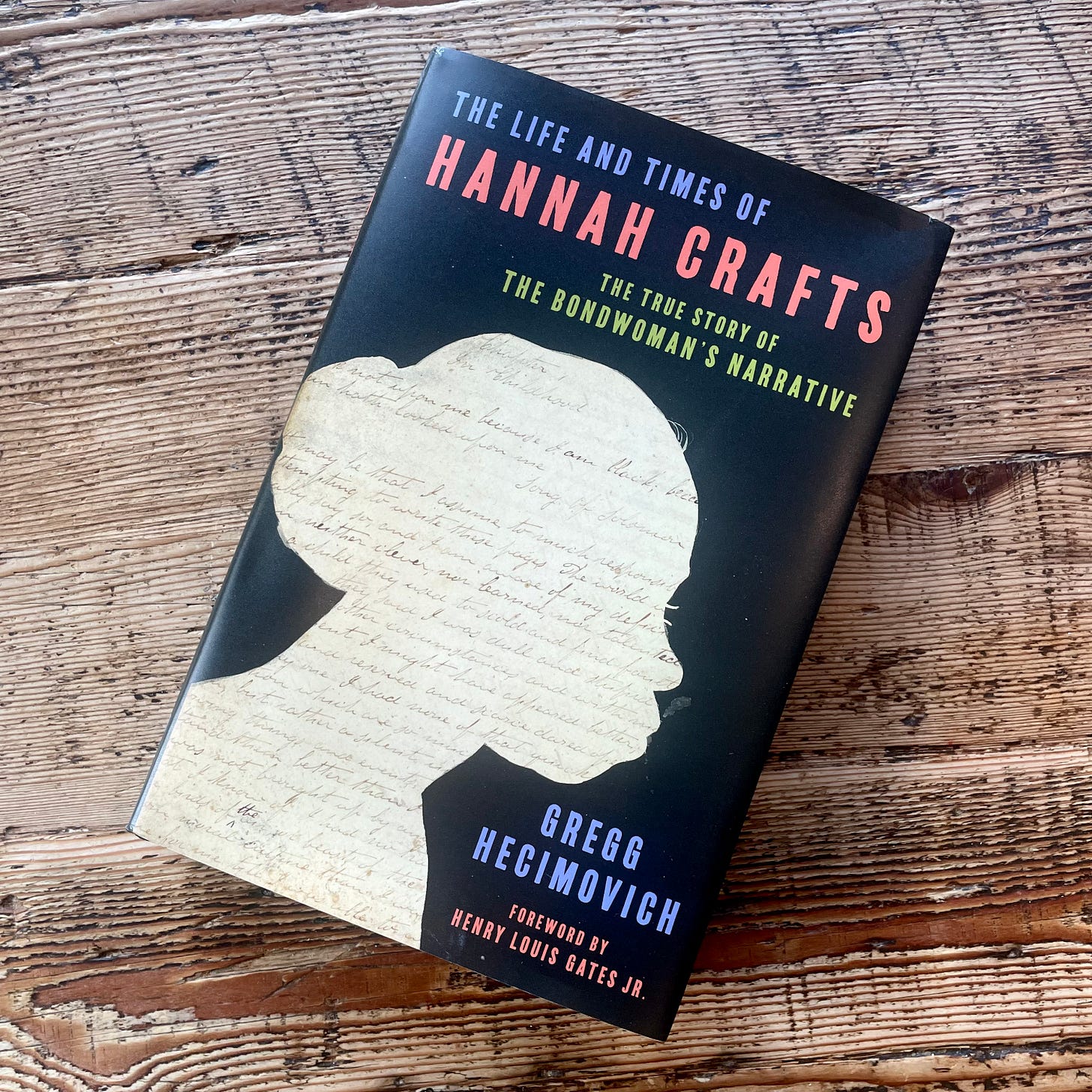

The story begins with a mystery. Sometime in the middle nineteenth century an unnamed author penned a semi-autobiographical novel about her ordeal in bondage and eventual escape. Though unpublished when written, the manuscript finally found its way into the hands of Henry Louis Gates Jr., who authenticated it, floated theories about its authorship, and saw to its publication—whereupon The Bondwoman’s Narrative became a New York Times bestseller after a century and a half of quiet hibernation.

But countless questions persisted, not least who wrote the book for certain. Gates invited scholars to pick up the work where he left off, and many answered the call, including University of Utah humanities dean Hollis Robbins, who we’ve interviewed before, and Gregg Hecimovich.

Hecimovich doggedly pursued the mystery for two decades, examining archives and papers, visiting sites, crosschecking family recollections and documents, census records, log books, personal journals, regional histories, library holdings, and the revelations of the manuscript itself until the true picture came into view.

And what a picture: A light-skinned black woman, the child of plantation rape, serves in a well-heeled and politically connected home in North Carolina, follows her enslavers to Washington, D.C., is handed off as a gift between family members, suffers sexual abuse by the nephew of her owner, and captures it all in a manuscript she secrets away until her break for freedom.

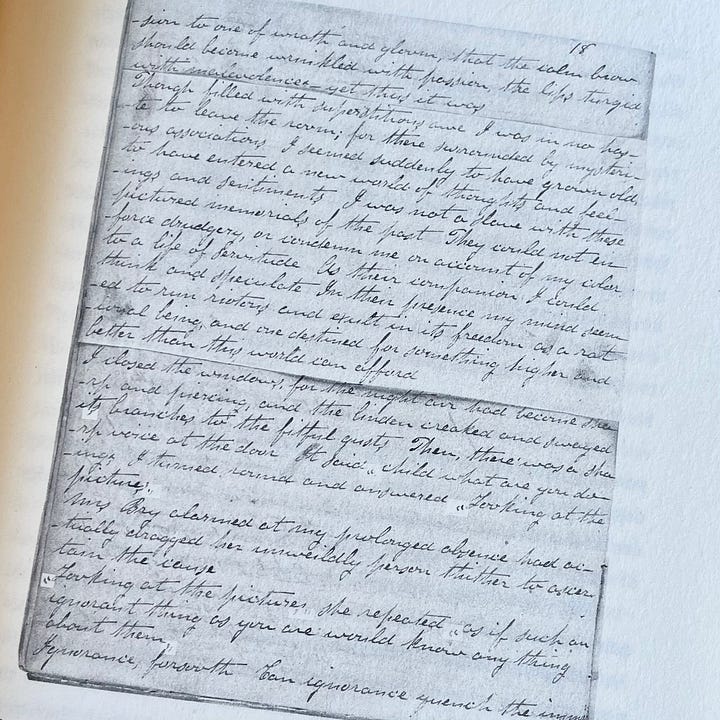

Unlike slave narratives sponsored and published by white abolitionists pursuing their own meaningful but narrow interests, the author’s narrative was solely hers and reflects no outside interests or agendas but her own. Considering she never identifies herself in the book, nor seems to have sought its publication, we can only assume it was written for personal, emancipatory purposes—a woman asserting her humanity against a dehumanizing, oppressive institution for the sake of her own dignity.

Read in the context of the accumulated evidence, the manuscript itself teems with identifying details, including personal and familial anecdotes fictionalized and repurposed for the narrative—for instance, a vindictive moment in which an enslaved woman and her dog are both hanged from a tree until dead by her owner.

Such corroborating instances show up in official and unofficial archives and triangulate back to one authorial candidate, a woman named Hannah Bond Crafts Vincent—each of those names reflecting a distinct stage in her life’s journey.

There are other candidates, but Hecimovich not only dismantles the case for each, he builds up the case for Crafts and takes it further than anyone had done before, including following the evidentiary trail to her life of freedom in the North, her years as a school teacher, her marriage and death in old age. From there he follows the path of the Hannah’s manuscript through its various but few owners until Gates acquired and published it.

Crafts’s life, as Hecimovich painstakingly reconstructs it, is one shaped by self-determination from her earliest years. Separated from her mother at ten years old, Crafts was forced to find her way in her master’s world largely on her own. Though formal education was denied, she surreptitiously learned to read and developed a love for literature and a devotion to its composition—evidenced by her adaptation of tropes and scenes from such books as Charles Dickens’s Bleak House in her own narrative.

While grounded in her own life, everything in The Bondwoman’s Narrative is refracted through the lens of gothic fiction, sometimes with with a satiric edge. In one instance, the wife of Craft’s owner pleads with a government official for an appointment on behalf of her husband, to whom she later recounts the moment:

“I gave your name as that of my husband, and when Mr. Cattell said ‘by courtesy perhaps’ I said ‘No, by law’ when they all burst into a titter.”

“Then you really asked Cattell for the office?” said Mr. Wheeler. . . .

“Certainly I did.”

“And what did he say?”

“That it was no customary to bestow offices on colored people. . . . ‘Then you positively refuse this office to my husband’ I said going down on my knees.”

What the woman failed to realize while she affirmed Mr. Wheeler as her husband and begged for his job on her knees? She offered her plea—thanks to a cosmetic mishap—entirely in blackface! Such a scene would be considered delightfully subversive for a modern black author. How much more so for a woman raised in slavery and writing on paper stolen from her master?

Such literary confidence shows how thoroughly Crafts had appropriated her role as author and used it to, as Hecimovich says,

wrest back a life otherwise stolen from her. . . . [S]he yearned to transcend her world by living intimately within a story she could help form. And, in many significant ways, the reimagined journey to freedom she portrays in The Bondwoman’s Narrative helped her realize the life she came to possess.

Crafts wrote herself out and followed her pen with her feet, disguised in men’s garb on her way up north. And every bit as astonishing as the tale of her escape is the fact that her book exists at all—and that a scholar such as Hecimovich, working a century and half later, could piece together the author’s life and identity: the earliest black female novelist in America.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

What a tale. I definitely want to read this now!

Adding to the list for sure!