Bookish Diversions: Type-Oh, Dang It!

Typos in James Joyce, the Bible, and Recent Books; Interpretive Liberties; More

¶ Oops. James Joyce’s Ulysses turned hundred a couple of years ago. More than two thousand errors supposedly blighted the first edition, published in 1922 by Shakespeare and Company in Paris.

We can blame the French printer’s lack of familiarity with English for some of the mess. But when London’s Egoist Press released another edition later that same year using the same plates, Joyce and his editors assembled an errata sheet—actually seven—addressing only a tenth of the total mistakes.

Making matters worse, a bootleg edition in New York introduced fresh new errors in 1929. When the Random House finally released an authorized version of the book five years later, it used this bootleg edition for its text and thus perpetuated the mistakes. As late as 1975, scholars attacked Modern Library’s 1961 edition for omissions.

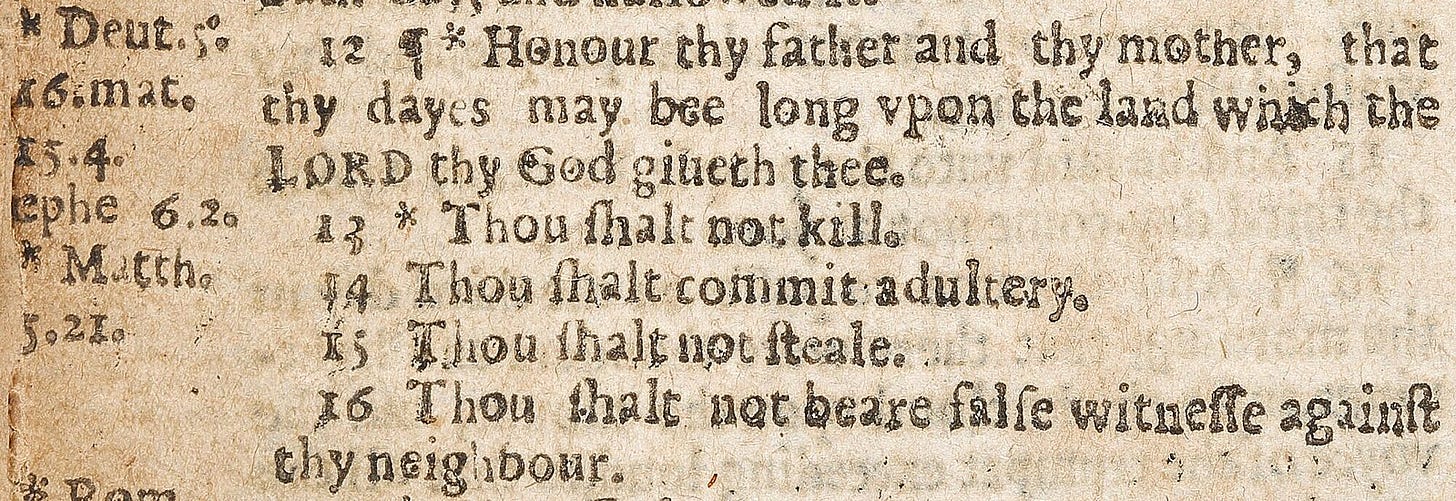

¶ Wicked Bibles. Typos are a regular part of publishing, always have been. Back in 1631, royal printers produced an edition of the King James Bible that inadvertently dropped the “not” from the command against adultery, rendering the verse “Thou shalt commit adultery.” The edition was subsequently dubbed the Wicked Bible or the Sinner’s Bible.

When the error was discovered, the printers lost their license, faced a massive fine, and were personally reprimanded by King Charles I. Imagine that scene. Most of the print run was burned, but as many as twenty copies escaped destruction and remain at large in the world today. A couple years ago one turned up in New Zealand. The Museum of the Bible keeps another on display.

The Wicked Bible contained an additional doozy. Deuteronomy 5.24 in some copies of this edition supposedly read, “And ye said, Behold, the LORD our God hath shewed us his glory and his great-asse.” That should have said “greatness.” The second error does not exist in surviving copies, but there’s evidence of its existence.

The appearance of two such monumentally embarrassing typos have led some experts to suggest that sabotage was afoot. But human error is all that’s necessary to bungle a line, or two, or more. Here are a few other famous Bible typos from other editions:

“Sin on more” instead of “no more”

“Let the children first be killed” instead of “first be filled”

“If the latter husband ate her” instead of “hate her”

“Out of thy lions” instead of “thy loins”

“Printers have persecuted me” instead of “princes”

Of course, that last one may be more accurate than it first appears.

In The Bible: A Global History, Bruce Gordon mentions John Baskett’s 1717 “elegant folio edition, so large that it was joked that it took a crane to lift it. . . .” Another distinctive? It was riddled with mistakes—so many that people referred to Baskett’s edition as “Baskettful of Errors.” Gordon mentions one: Baskett rendered the parable of the vineyard in Luke 20 as the “parable of the vinegar.” Says Gordon, “It is inviting to think what Jesus’s vinegar teaching might have been.”

¶ Portals of discovery? A wonderful article by Ed Simon on typos and misprints points to a few such pips, including “Blessed are the placemakers” instead of “peacemakers” from the Sermon on the Mount. But Simon goes beyond and looks at many modern cases as well, including when HarperCollins printed 80,000 copies of Jonathan Franzen’s novel Freedom with the rough draft of the manuscript instead of the final. They sold about eight thousand copies before anyone noticed.

Simon’s essay begins with a quote from Joyce’s Ulysses, ironic given the book’s many errors: “A man of genius makes no mistakes. His errors are volitional and are the portals to discovery.” Humorously enough, that very line has been misprinted and misquoted over the years.

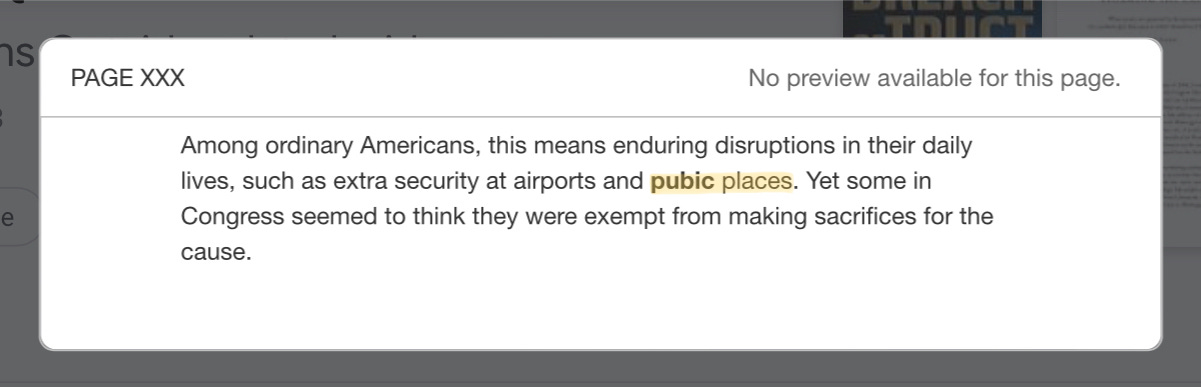

¶ My mistake(s). I have two typo stories that stick with me from my publishing days. Then-Congressman Tom Coburn’s book, Breach of Trust, referenced “extra security” at “pubic places” instead of “public places.” The fact that this goof occurred on page xxx made it all the more ridiculous. We fixed it on the next printing; the corrected file is in the Amazon preview, but Google still has the old file.

By far the most humiliating typo of my career was “countertearooms experts,” instead of “counterterrorism experts.” We published a book by David Bossie on President Clinton’s national security policies. Bossie argued that those policies paved the way for Bin Laden and the 9/11 attacks.

Famed political pundit Robert Novak agreed to write the foreword at the last minute—and I mean at the bleeding, pulsing, final seconds. We added Novak’s name to the cover and held space in the book to drop in the text, asking the printer to wait until we had it. A Novak foreword was certain to boost sales. But time was tight.

We’d already blown up the regular schedule, and now we were testing the patience of the printer. Just as they called to inform us they were bumping our place in line, the foreword hit my inbox. Hang on! I gave it a quick once-over and handed it to a colleague who proofed it. We then sent it to the typographer who set the pages and sent them to the printer. Amazingly, we slipped it in just in time.

Then Bossie called me about four weeks later.

He had just received his copies and was reading through Novak’s foreword with all the pride he might justly feel. And then he landed on “countertearooms experts.” God help me. Perhaps it’s good that neither Amazon nor Google have previews of the mistake to document my mortification. I think the best we were able to tell, the error was in Novak’s original file but my proofer and I both skated right past the mistake.

¶ Muphry’s Law. You’ve heard of Murphy’s Law. Muphry’s Law—note the intentional typo—applies it to the typographic. It states, “If you write anything criticizing editing or proofreading, there will be a fault of some kind in what you have written.” I’ve noticed several in this piece already and fixed them as I worked. I bet there are more.

According to Microsoft, their users punch backspace more than almost any other key on the keyboard. As a Mac user, for me it’s delete, delete, delete. All day long. But stuff still gets through. Why? Our brains are efficient. We don’t brute-force process everything we read. We utilize prediction to save energy and speed up our work; our brains take in just part of what the eyes scan and fill in the gaps.

But there are tradeoffs for this efficiency. I, for instance, expected to see counterterrorism in Novak’s draft; so, when my eyes spied countertearooms, my brain supplied the right word, though the wrong one actually stared back from the screen.

This problem is all the more bedeviling when it comes to our own words. The power of prediction amplifies. As Nick Stockton writes for Wired,

When we’re proof reading our own work, we know the meaning we want to convey. Because we expect that meaning to be there, it’s easier for us to miss when parts (or all) of it are absent. The reason we don’t see our own typos is because what we see on the screen is competing with the version that exists in our heads.

It turns out familiarity breeds gaffes as much as contempt, probably more so. Stockton continues,

This explains why your readers are more likely to pick up on your errors. Even if you are using words and concepts that they are also familiar with, their brains are on this journey for the first time, so they are paying more attention to the details along the way and not anticipating the final destination.

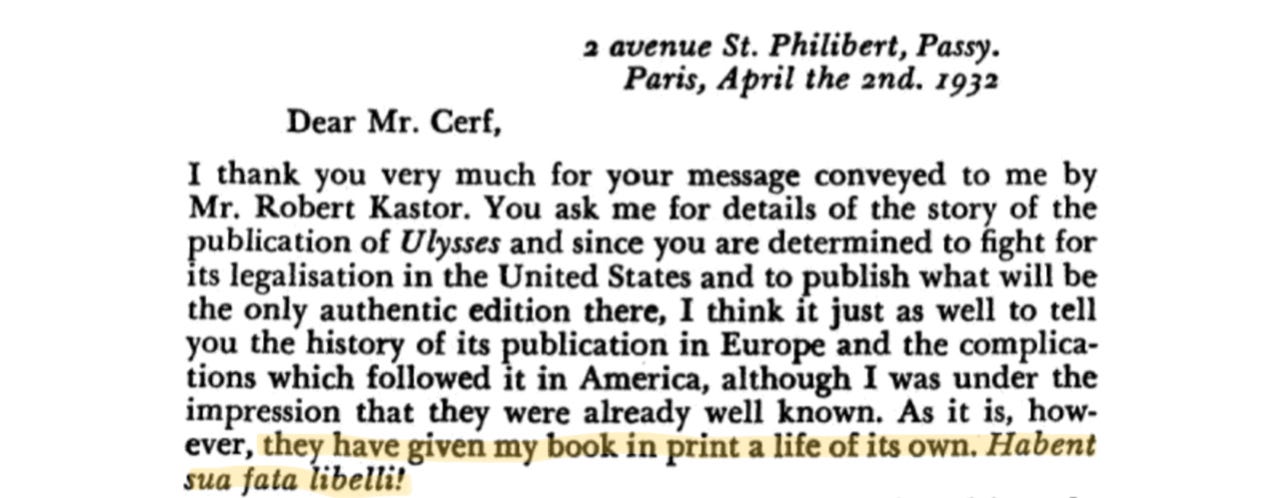

¶ Readers give books a life of their own. As seen briefly above, James Joyce’s Ulysses had a strange and troubled publishing history, including being banned in multiple locales—the U.S. among them—for obscenity. When writing Bennett Cerf at Random House for help in releasing an authorized version in the American market, Joyce mentioned that Ulysses had taken on a life of its own.

“They have given my book in print a life of its own,” he said, adding the Latin phrase, “Habent sua fata libelli”—“Books have their own destinies.”

The line goes back to the late third century and was first used in full by grammarian Terentianus Maurus in his book De Litteris, De Syllabis, De Metris:

Pro captu lectoris habent sua fata libelli.

Translation: “According to the capabilities of the reader, books have their destiny.”

I’ve always found this idea fascinating because it recognizes that a book is not merely a message from an author; it’s also an interpretive enterprise of readers and communities of readers. It’s one of the reasons typos matter—misprints might affect the message. Back to those portals of discovery. But even perfectly communicated messages can have meanings unintended by their senders. Three relevant quotes come to mind:

Gordon S. Wood, “Machiavellian Moments”:

Books belong to their readers, not their authors.

Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners:

It takes readers as well as writers to make literature.

Jerzy Kosinski, Passing By:

Books remain the most important means of expression because books are democratic in that they grant readers the freedom to interpret their meaning. . . . A book, like a culture, says to its reader: My dear, I’m yours. You are free to do with me what you will. I am your entrance into yourself and into history at the same time.

Terentianus seems to be focused on the limitations of a reader, according to this note in the James Joyce Quarterly. But it goes both ways: Readers bring new ideas to books as much as they might miss what’s already there.

It’s impossible to imagine, for instance, the divide between Christian and Jewish reading communities regarding the Hebrew Bible without factoring interpretive liberties. It’s also, as James Kugel points out in How to Read the Bible, impossible to imagine the divide between Jewish reading communities of different historical periods: same book, same readers, different understandings.

A book is always more than what the author intends.

¶ Portal to the Western canon. And why should we bother with James Joyce these days? Let me quickly admit I haven’t, though in my teens I was enthralled by a book on all the allusions in Ulysses. It was almost as long as the novel itself. Nathan M. Antiel hones in on these allusions as a major reason for picking up the novel today.

Joyce weaves so many elements together, he says, it’s a delight to tease them out and see how they work in the narrative:

Joyce simultaneously retells Homer, the Gospel of John, Dante, Hamlet, Paradise Lost, and more. . . . Ulysses is a book of many books: while the parallel with Homer is unfolding, we also see Stephen echo Hamlet and Milton’s Satan at turns. Thus the more you’ve read, the more you’ll find in Ulysses.

But the truly magnificent thing is the seamless way in which this is all woven together. Ulysses is a veritable encyclopedia, a bona fide microcosm of Joyce’s vision of the western literary tradition. And because of that, it just might change the way you read.

I quickly found I couldn’t escape Ulysses. . . .

But it’s not only the big texts in the western tradition which appear in some form or another in Ulysses. The text is so comprehensive it’s hard to say what it doesn’t engage or reference or rewrite. In fact, Joyce once joked, “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.”

Seen in this light, Ulysses becomes an introduction to—and eduction in—the western canon.

¶ Not misprints but beauties. All those typos bothered Joyce at first. “I am extremely irritated by all those printer’s errors,” he said looking at the page proofs. “Are these to be perpetuated in future editions? I hope not.” But then, curiously, he decided not to rectify them all.

Some he came to love. When fixes were suggested, he turned many of them down, saying, “These are not misprints but beauties of my style hitherto undreamt of.” Writes Sam Slote,

To claim that something is wrong, you have to know what is right, or, improving ourselves, you have to think you know what is right. There are several ranges of response to error, for example, one can be a pedant and criticise. This is the scholarly response, something academics are paid to do. There is obviously a place for such nit-picking. But it’s not necessarily an end in itself. In a human world, there has to be a place for human quirks and foibles and blunders. . . . This is perhaps the lesson of Ulysses, the affirmation of the messier parts of life, even typos.

Still, let’s triple check that file, shall we?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

While you’re here:

I always enjoyed the mistyped version of Bulwer-Lytton's ringing phrase 'The pen is mightier than the sword', after the printer ran the second and third words together.

And one of my favourite stories about an editor's error is the last line of Nabokov's short story 'Bend Sinister', which to his annoyance was turned from "A good night for mothing" into "A good night for nothing". What you might call the mother of all misreadings.

Miller's Book Review, "Typos in James Joyce") I can't help editing and proofing as I read anything and everything. It seems to be a mental tic with me. Advanced education in Latin, English and linguistics studies may be the cause. Hence in a long reading history I've (reluctantly) had to track (inevitable) evolutionary changes in the denotations of words. There's one of my least favourites in this piece - "honing in". Originally, "homing in". To hone: to sharpen a tool. To home in: to focus more closely on as target. Well, it's too late now to salvage that particular word. Thus a little more of the linguistic precision I treasure declines to fuzziness in everyday usage. (cf use of "to beg the question" when "to raise the question" is intended - very fuzzy).