Editing: Scratch That, Try This Instead

On the Power of Revision: Isaac Newton, J.K. Rowling, Ernest Hemingway, Joan Didion, Peter Drucker, Others

The subject of editing, revising, and correction can cause some writers to shudder. Rewriting presents a challenge some would forever forestall if possible. As an editor, I once worked with an author who delayed revisions for weeks, months, long after we sent him notes on necessary changes in his manuscript. He dawdled so long it threatened our release schedule.

Thankfully, while visiting the office for a marketing meeting, he finally produced an updated copy of the manuscript, printed entirely on goldenrod paper(!), covered in handwritten notes and strikethroughs. It was as though he couldn’t bring himself to sit with his computer and work on it any longer, as if the first time through proved traumatizing enough.

Instead, he required the distance afforded by real paper and a ballpoint pen and just hoped we would backfill the effort by implementing his changes in the file. God help the copy editor who had to decipher his handwriting.

When I think about this sort of agony, I wonder: Are we making this harder than it needs to be? For starters, aren’t we complicating matters by dividing these stages, writing and rewriting? Aren’t they much the same?

A Writer’s Work Is Never Done

The prefix “re” is unnecessary, possibly misleading. Have you actually finished writing if you’re now rewriting? Maybe it’s helpful to divide the process in two and assign different labels, but we might normalize revision for ourselves if we simply see it as part of the same continuous process.

In 1687 Isaac Newton published his Principia Mathematica, a book that revolutionized study of the natural world and the conceptual frameworks that support it. It was also full of errors and faulty expressions. In 1713 he issued a second edition with heaps of changes to the first, helped by an ambitious editor. Here’s a picture of Newton’s own copy of the first edition with notes for revision. Notice the scribbles and crossouts; there are revisions within the revisions.

The only thing weird about Newton’s revisions were how long it took him to actually make the changes and release the second edition: twenty-six years! Says A. Rupert Hall, writing an account of the revision,

It does not seem to be clear why the Principia was not re-issued in the 1690s, nor why in 1708 Newton decided to bring it out at last in a revised form. [Royal Society member and Newton colleague Richard] Bentley was the successful instigator of a new edition; the story has it that Newton allowed him to undertake it for profit “because he was covetous and wanted money.”

No judgment; money’s nice. Then in 1726—a full thirty-nine years after the first edition—Newton issued a third edition with additional refinements and updates. A mathematician’s work is never done. And that’s pretty much true for any serious writer.

Various Methods

Critic Darryl Pinckney has written about his relationship with fellow writer Elizabeth Hardwick. He mentions one encounter with his mentor, relevant to the subject at hand: “She talked about the joy of revision; she talked about the pain of revision, too, and said that anyone who couldn’t bring himself or herself to face it couldn’t be a real writer.”

“My first drafts always read as if they had been written by a chicken,” Hardwick told Pinckney.

For Italian journalist and novelist Italo Calvino revision was essential to his final product. New ideas emerged as he worked; only with multiple rounds could those ideas come to the fore. He talked about his writing process with the Paris Review:

I write by hand, making many, many corrections. I would say I cross out more than I write. I have to hunt for words when I speak, and I have the same difficulty when writing. Then I make a number of additions, interpolations, that I write in a very tiny hand. . . . My pages are always covered with canceling lines and revisions. . . . After the first draft, written by hand and completely scrawled over, I start typing it out, deciphering as I go. When I finally reread the typescript, I discover an entirely different text that I often revise further. Then I make more corrections. On each page I try first to make my corrections with a typewriter; I then correct some more by hand. Often the page becomes so unreadable that I type it over a second time.

Novelist Jasmine Guillory recently described her revision process in an exchange with Nicole Chung at the Atlantic. It’s a little more advanced than Calvino’s method; the variation just shows that every writer has to find their own process and there’s no one way to accomplish this essential task.

“I have a big revision spreadsheet,” Guillory said. “Each draft is in a different tab. I create a column for each chapter, and add notes about things I want to cut and change. By the time I get to the end of the first draft, I can visualize the entire book in the spreadsheet, and I have a record of a lot of the changes I want to make in the next one.”

J.K. Rowling also used a spreadsheet method for revisions to Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. It’s just that hers was entirely handwritten. You can find a transcription of her handwriting here. At least it’s more legible than Isaac Newton’s.

Drunk or Sober?

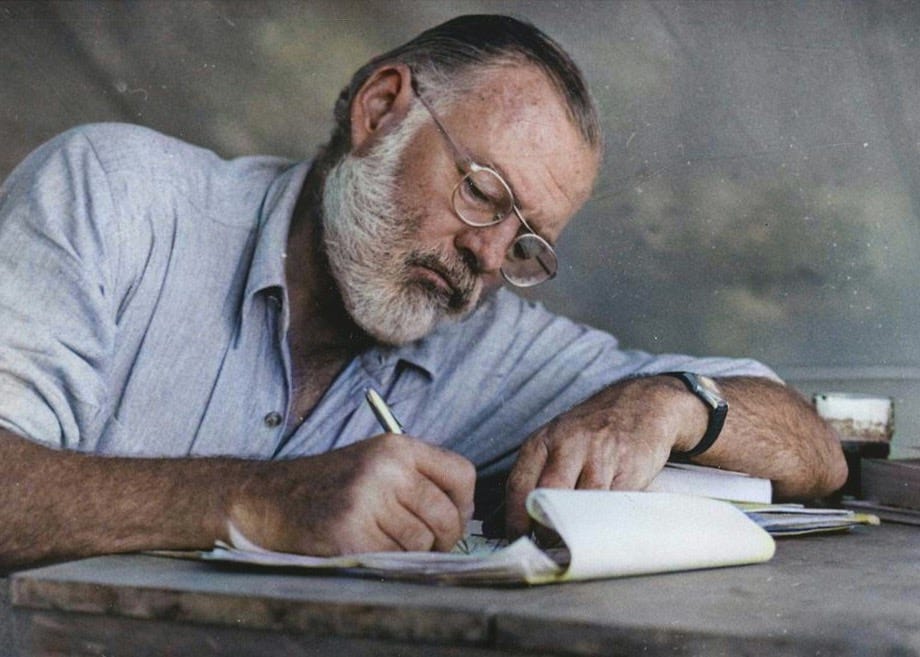

Are their any methods that don’t work? It’s probably best to avoid the advice misattributed to Ernest Hemingway: “Write drunk, edit sober.” For one thing, he actually advised against it. When asked if he took “a pitcher of martinis up into the tower every morning when you go up to write?” Hemingway objected:

Have you ever heard of anyone who drank while he worked? You’re thinking of Faulkner. He does sometimes—and I can tell right in the middle of a page when he’s had his first one.

Joan Didion recommended the reverse, writing sober and editing after a drink. “When I finish work at the end of the day, I go over the pages, the page that I’ve done that day, and I mark it up,” she said. “And the drink loosens me up enough to actually mark it up, you know. . . . Really, I have found the drink actually helps.” Didion rewrote every morning, retyping all her pages and changes from the prior day—as many as a hundred pages at a time.

The idea behind the Hemingway misattribution is that one should be free and associative when writing and clear-eyed and focused when editing. But, again, doesn’t that creates a bogus divide? Part of writing is looking for the right formulation, the exact phrase, in whatever state of mind you’re in. If you don’t get that on the first pass, you get it on the second, or the fifteenth, or the fiftieth. But it’s the same basic enterprise.

And the hunt for the right formulation is an elevated pursuit. “Revision teaches me how to push beyond the choices that come easily,” says poet Traci Brimhall. “It restrains me, challenges me, forces me back and back and back again to my failures. Process saves me from the poverty of my intentions.”

An Enjoyable Process

I actually find editing and revision something of a leisure activity. Pronounce me tetched, but I love it. I resonate with this bit from Peter Drucker. After wrestling through what he calls a zero draft, “the one before the first draft,” he says a writer is free to poke away at it, to dip in and out, to tweak and adjust as time and whim permit. After getting the zero draft, “one can indeed work in fairly small installments, can rewrite, correct, and edit section by section, paragraph by paragraph, sentence by sentence.”

Like any job, it’s all in how you conceive it. As YA writer N.D. Wilson says in The Dragon’s Tooth, “Everything gets harder if you start going on and on about how hard it is.” Then again, Hardwick did talk about the joy and pain of revision. Mileage may vary.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Seems like you have Stephen King's "On Writing" on your list this year? You'll love his advice for writing and rewriting.

There’s a delicate balance between revising and over revising—cutting too deep and not cutting deep enough. George Saunders wrote about this in his recent Office Hours newsletter. It’s worth a read: https://open.substack.com/pub/georgesaunders/p/office-hours-95a?r=6p55p&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post