Hunger for Connection: Being Known by Finding Your Voice

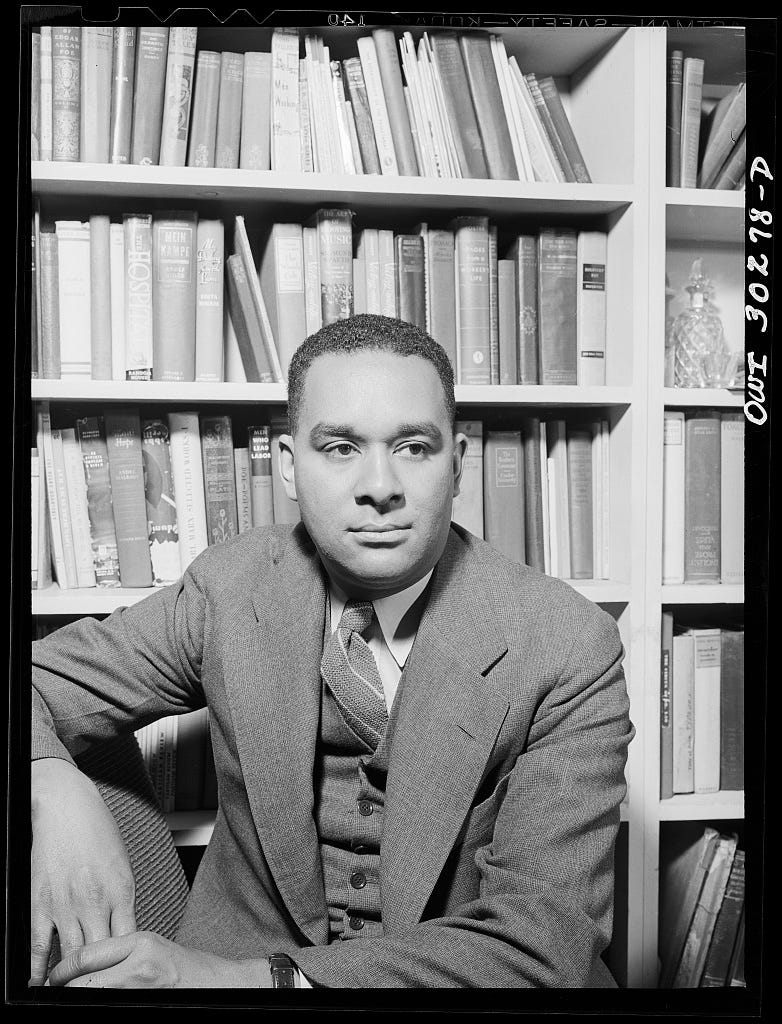

Fighting with Words: Reviewing Richard Wright’s Classic Memoir, ‘Black Boy (American Hunger)’

A nineteen-year-old Richard Wright thumbed a copy of the Memphis Commercial Appeal, landing on an editorial denouncing the famous—or infamous—newspaperman and critic H.L. Mencken as a fool.

“I felt a vague sympathy for him,” said Wright. The only people denounced in southern newspapers, as far as Wright knew, were people who looked like him: black. But Wright knew Mencken wasn’t black. He earned the editor’s vitriol from his ideas alone, and Wright instantly knew he wanted to read those for himself.

Just one problem: As a black person, Wright was barred from borrowing books at the local library. No worries; he had a plan.

Wright approached a coworker. Being Irish Catholic, the man was socially marginalized like Wright. But he was white—and that meant he could get a library card. In fact, Wright had picked up books for the man before. He could do so again, but this time he’d just keep the books to read for himself. His friend agreed.

Armed with a borrowed library card and a forged request, Wright secured a copy of Mencken’s A Book of Prefaces and also his Prejudices. “I was jarred and shocked by the style, the clear, clean, sweeping sentences,” he said.

This man was fighting, fighting with words. He was using words as a weapon, using them as one would use a club. . . . Occasionally I glanced up to reassure myself that I was alone in the room.

Wright was smart to be worried. Entertaining such thoughts in the presence of southern whites was likely to end in violence. Social structures and strictures had evolved to keep blacks in check, and those who didn’t play along found themselves subject to shocking brutality. In Mencken’s rowdy, irreverent prose, Wright found a space where he could push back, even if only in his mind.

Reading the World

Born in 1908 to poor parents with a doomed marriage that ended when he was young, Wright’s upbringing was marked by deprivation. He had little to eat and schooling was catch-as-catch-can. He was almost a teenager before he ever had a regular year of class.

He learned to read, regardless. Neighborhood kids would play in the streets after class, leaving their books on the curb. “I would thumb through the pages and question them about the baffling black print,” he said. “When I had learned to recognize certain words, I told my mother that I wanted to learn to read and she encouraged me.” The two would sit and read the Sunday paper together, Mom nudging and guiding him down the columns of text. “Soon I was able to pick my way through most of the children’s books I ran across,” he said.

With their father having abandoned them, the little family found their financial situation unsustainable. Mom, son, and younger brother moved in with the family matriarch, a harsh Seventh Day Adventist born in the days of slavery, whose economic condition was only marginally better than their own and who possessed no appreciation for Wright’s budding love of literature. On the contrary, Grandma was vitriolic in her opposition.

There in her Jackson, Mississippi, home Wright’s grandmother boarded a school teacher. One day while sitting on the front porch, the teacher read him Bluebeard and His Seven Wives at Wright’s prompting. Before she could finish, the old scold interrupted. “You stop that!” she yelled. “I want none of that Devil stuff in my house!” When Wright protested, she backhanded him.

While physical hunger plays a recurring theme throughout Wright’s two-part narrative, his more fundamental hunger was the desire to be seen and known as his genuine self. Unfortunately, his family and the wider community denied him that understanding throughout his trying childhood and teen years.

What connection he did experience was often violent. He never could quite accept the faith of his family, nor could he avoid getting on the bad sides of his grandmother, aunts, and uncles. He struggled to know how to act toward whites, some of whom threatened his life. He could read a book, but it took him longer to learn how to read people.

Still, reading—and then writing—would form a way out.

Finding a Wider World

As an adolescent Wright took a job selling newspapers to make money. He loved reading the stories in the fiction supplement. Unfortunately, the news section printed pieces supporting the KKK. When a neighbor pointed out the problem, Wright quit the paper and found other ways to make money.

He hoped to get a job at local black newspaper, though regular work never came. What did come was encouragement. Wright submitted a piece of fiction he’d written, and the editor decided to run it.

Maybe he could become a writer? Not if his family had a say. Grandma considered fiction mere lies, and no one in his impoverished circle shared any interest in supporting his aspiration. Instead, that dream faded until he finally left town and found his way to Memphis where, years later, he read those fiery words of Mencken.

The Sage of Baltimore cracked open a fissure in the wall of Wright’s familial and cultural prison, and a different world came pouring in, one populated by strange persons with stranger names.

Who were these men about whom Mencken was talking so passionately? Who was Anatole France? Joseph Conrad? Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, Dostoevski, George Moore, Gustave Flaubert, Maupassant, Tolstoy, Frank Harris, Mark Twain, Thomas Hardy, Arnold Bennett, Stephen Crane, Zola, Norris, Gorky, Bergson, Ibsen, Balzac, Bernard Shaw, Dumas, Poe, Thomas Mann, O. Henry, Dreiser, H.G. Wells, Gogol, T.S. Eliot, Gide, Baudelaire, Edgar Lee Masters, Stendhal, Turgenev, Hunker, Nietzsche, and scores of others? Were these men real? Did they exist or had they existed? And how did one pronounce their names?

Mencken was the gateway. And the fissure that allowed new beams of light inside also allowed Wright the means of looking out—and eventually walking out.

I had somehow overlooked something terribly important in life. I had once tried to write, had once reveled in feeling, had let my crude imagination roam, but the impulse to dream had been slowly beaten out of me by experience. Now it surged up again and I hungered for books, new ways of looking and seeing. It was not a matter of believing or disbelieving what I read, but of feeling something new, of being affected by something that made the look of the world different.

Wright began chipping away at the fissure, widening it by his own effort. He read novelists Sinclair Lewis, Theodore Dreiser, and others, often reading on the sly to avoid the curiosity and suspicion of those around him. As he read, his waking reality became less tenable by the day. The racial repression, the enforced servility—once exposed to a wider world of seeing and feeling, it all felt impossible to bear any longer.

Black Boy ends with Wright escaping Memphis for Chicago, but it’s not the end of the story.

Writing the World

Mencken used words as a bludgeon, and Wright wondered if he might, too. “Maybe, perhaps, I could use them as a weapon?” he wondered. “No,” he said. “It frightened me.” But here we are, reading Wright’s autobiography, written years after and amid many other books, including his wildly popular 1940 novel, Native Son. How exactly Wright found his voice is contained in a second book, American Hunger.

Originally, they were one. Wright began working on his autobiography in 1943, then titled Black Confession and later American Hunger. The following year, he submitted the manuscript to Harper for publication.

While preparing the book for publication Wright’s editor, Edward Aswell, sent it to the Book-of-the-Month Club. They showed interest but only in the first part, which Wright retitled Black Boy—the section that ranged from Wright’s childhood to his departure for Chicago. But it was in Chicago that Wright became a writer.

He moved there in 1927 with his aunt Maggie in hopes of helping his mother and brother move next. He found work soon enough but also found the adjustment challenging. Economically the situation only worsened as the Great Depression arrived two years after they did. Thankfully, the literary impulse that inspired his move provided him purpose amid the difficulty.

Before long Wright discovered a community of writers in the John Reed Club, a national literary society sponsored by the Communist Party. With his talents finally nurtured, he developed his skill and showed the kind of promise that drew attention from higher-ups in the party. That had drawbacks of its own.

While Wright remained in ideological sympathy with the party, he found the organization and its goals stifling, and the group suffused with paranoia. When he decided to write profiles of leading local communists, party members grew suspicious of his motives. As he objected, he found himself marginalized.

Backhanded again.

Wright fled the South to escape domineering structures and isolation and found the same among his comrades in the North. He would need to look elsewhere to be seen and known.

Hunger for Connection

When it was published in 1945, Black Boy was an astonishing success, selling over a half a million copies between Harper’s trade edition and the Book-of-the-Month Club edition. But it’s almost impossible to imagine the book now without the second half.

While bits were published in magazines (e.g., “I Tried to Be a Communist” in Atlantic Monthly and “American Hunger” in Mademoiselle), part two of Wright’s original narrative wasn’t published in full until 1977, thirty-two years after Black Boy and seventeen years after Wright’s death in 1960.

While Black Boy begins with an epigraph from the Book of Job referring to the confused and benighted state of the culture in which he was raised, American Hunger begins with the lyrics of a Negro folk song about the hunger to be known: “Sometimes I wonder . . . if other people wonder . . . just like I do!” It closes on a note of reserved hope that writing might offer a path to connection:

I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all, to keep alive in our hearts a sense of the inexpressibly human.

Black Boy (American Hunger) was the third book in my classic memoir goal for 2024. Here’s what I’ve reviewed so far and what’s in store for the rest of the year:

January: Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

February: Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

March: Richard Wright, Black Boy

April: Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

May: Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland

June: John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

July: Stephen King, On Writing

August: Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

September: Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

October: John Stuart Mill, Autobiography

November: C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

December: Beryl Markham, West with the Night

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

You're an excellent writer and your reviews are always evocative and engaging. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for this review. Wright’s autobiography and novels are part of my library. Did you know later in life, when he was sick & dying, and living in Paris he wrote hundreds of Haiku? His daughter compiled his Haiku into a book.