C.S. Lewis: Before Narnia

When We Didn’t Know Jack. Reviewing ‘C.S. Lewis in America’ by Mark Noll

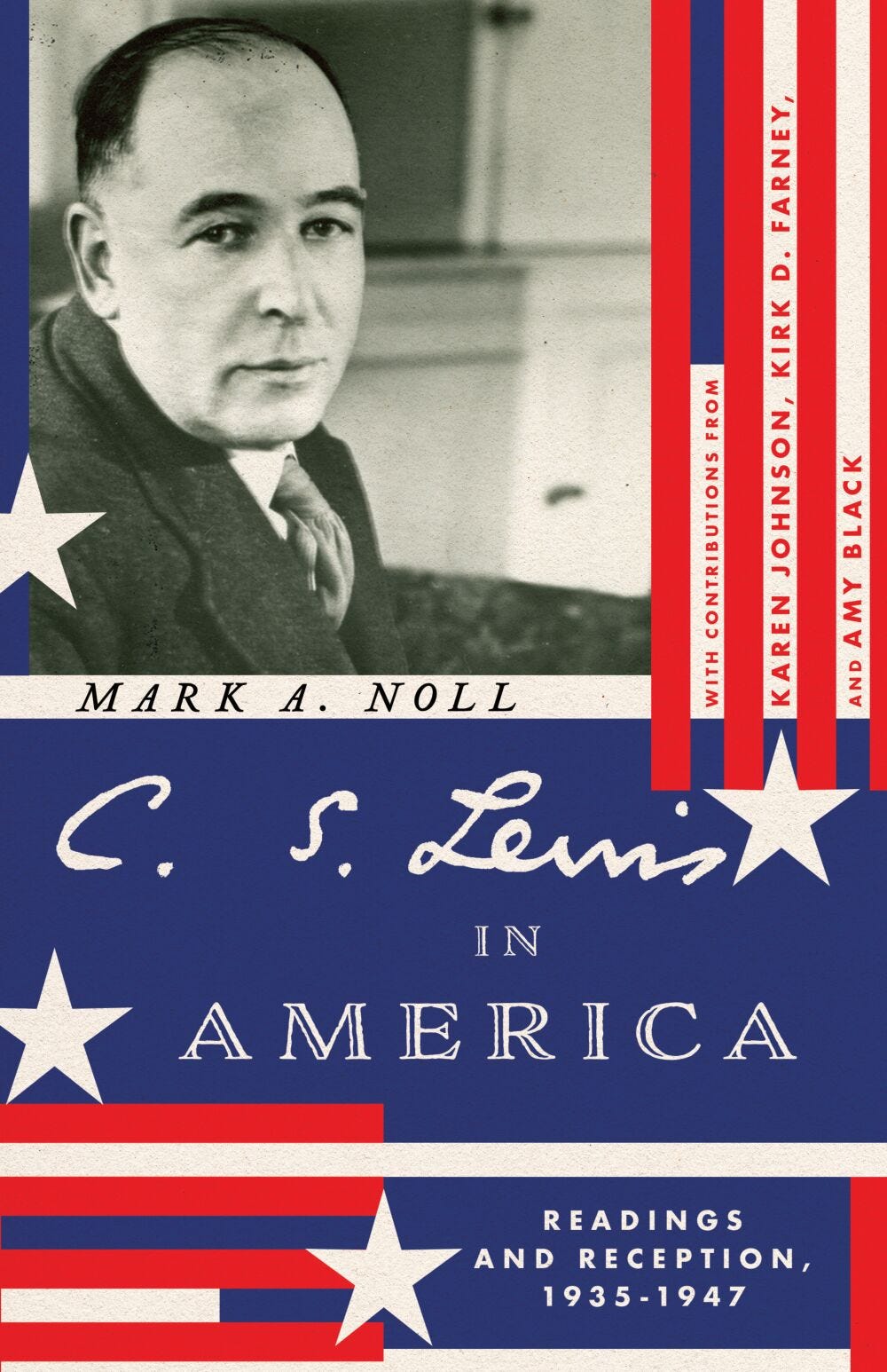

All told, his books have sold something like 200 million copies. Hundreds of books have been written about him and more are constantly added to the pile. One of the most recent? A slender volume by historian Mark A. Noll revisiting a time before C.S. Lewis’s gargantuan reputation became unavoidable.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the first book in the Chronicles of Narnia series, wasn’t published until 1950, Mere Christianity not until 1952. Meanwhile, Lewis had been publishing for nearly two decades—longer still if you count his pseudonymous work. What did people think of him? Specifically, what did they think of his work an ocean away from his homeland?

Based on new and extensive archival research, Noll answers that question in C.S. Lewis in America: Readings and Reception, 1935–1947. He does so by exploring three different genres in which Lewis wrote and three different audiences who read and reviewed his books.

Initial Readers

Noll divides Lewis’s books into three categories: literary scholarship, imaginative writing (fiction), and Christian exposition. And the primary audiences for these books? Noll looks at the reaction to Lewis by American Catholics, secular and mainstream readers, and Protestants—both mainline and evangelical.

During this period, the prolific Lewis published seventeen books, though not all were available in the U.S. market on the same schedule as in England. In 1935, for instance, The Pilgrim’s Regress hit American shelves, garnering only passing interest, mostly from Catholic reviewers and lonely review in the New York Times. By then, the British edition had been available for two years (though the allegorical novel was hardly a bestseller in either country).

The geographical discrepancy was more pronounced with The Allegory of Love, an academic work on medieval and Renaissance love poetry. The book saw British publication in 1936 but only twenty-two years later in America. Despite its limited distribution, it was read and reviewed stateside, as were his other academic titles; before his vocation as a monastic, Thomas Merton(!) reviewed The Personal Heresy (1939) for the New York Times.

Early on, the primary interest in Lewis and his work came from scholarly, secular quarters, though not enough to spark wider interest. Evangelicals—who would later become a key constituency, with some affectionately and ironically referring to Lewis as St. Jack—gave him virtually no love in these years, even though he had published explicitly Christian material.

No, the real breakout for Lewis came only after he made a deal with the devil.

Screwtape Opens Doors

The Screwtape Letters created Lewis, or at least the popular perception of him as an author. An epistolary novel that he confessed discomfort writing for all the difficulty of inhabiting the character of a senior demon, Screwtape, mentoring his newbie nephew on the ruination of souls, it became the one book for which he was best known until Narnia.

There’s a visual nod to the novel’s reputation-forging power on Time magazine’s September 8, 1947, honorific cover at the end of the period covered by Noll. An angelic figure hovers out of frame with just the hint of halo and the spread of single wing. Meanwhile, Old Scratch stands proud in full devil regalia: pitchfork, horns, tail, and goatee, amusingly pushing Lewis off-center. It’s as if Lewis is being edged over to make room for Satan.

No worries: After Screwtape, everyone began making room for Lewis. You can see this in the publishing history. Noll provides a table of the UK–U.S. market split of Lewis’s books published from 1935 to 1947. In England Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet came in 1938, The Problem of Pain in 1940. Then came Screwtape in 1942, along with Broadcast Talks (better known as The Case for Christianity) later that same year.

It took another year for Macmillan to release their U.S. edition of Screwtape, but once the public responded so enthusiastically they rushed several more titles to press. Outside a few academic titles published by Oxford University Press, Lewis published nothing in the U.S. from 1936 until 1943. Then, all this came in a flood:

February 16: The Screwtape Letters

September 7: The Case for Christianity

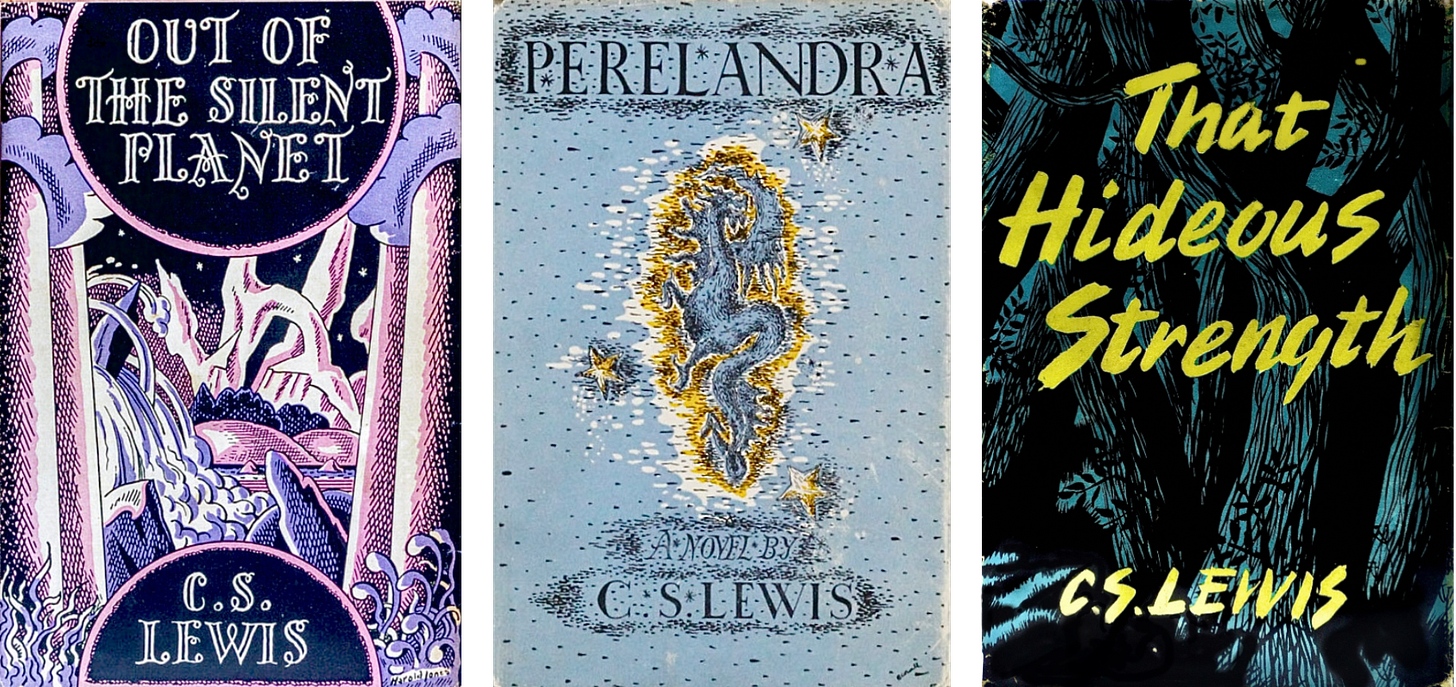

September 28: Out of the Silent Planet

October 26: The Problem of Pain

And it kept coming. Macmillan released two more Lewis titles in 1944 (Perelandra and Christian Behaviour), two more in 1946 (The Great Divorce and That Hideous Strength), and three in 1947 (The Abolition of Man, Miracles, and George MacDonald). 1945 was the outlier with a single title (Beyond Personality).1 Lewis went from being a fairly obscure if interesting Oxford academic to a publishing phenom.

‘Startling Wit’

While Catholics and academics demonstrated the first real attraction to Lewis in America (his only publishers in the U.S. until Macmillan released Screwtape were the Catholic house Sheed & Ward and Oxford University Press’s New York office), mainline Protestants joined the chorus. Though some criticized his more conservative tastes and takes, most granted his work earnest attention, as did secular media—especially where his fiction was concerned.

Publications that reviewed Screwtape, The Great Divorce, Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength included the New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Atlanta Constitution, and the Los Angeles Times. While Alastair Cooke was unimpressed (“a minor prophet, pressed into making a career of reassurance”), Lewis found himself favorably compared to G.K. Chesterton, Aldous Huxley, and H.G. Wells.

Lewis, said Leonard Bacon, covering Perelandra for the Saturday Review of Literature,

has a powerful, discriminating, and, in the proper sense of the word, poetic mind, startling wit, an overwhelming imagination, a charming and disarming naiveté, and the capacity to express himself. . . . In so short a notice it has been impossible to give a notion of the freshness and clearness, the unpretentious nobility of the fable and the thought.

American Catholics were similarly impressed with Lewis’s fiction. Their complaint lay with his nonfiction, though not all of it, nor even most. Catholics were particularly irked by what otherwise favorable reviewer Anne Jackson Fremantle referred to as Lewis’s “picayune view of the Church” emerging from his doctrinal books. Not surprising, really. Lewis was a mid-church Anglican with little formal interest in ecclesiology. His pre-Vatican II Catholic readers were rather more sensitive to the issue.

For their part, evangelicals were sensitive to far more, though Lewis’s increased notoriety in this period eventually made him impossible to ignore.

Evangelicals Come Around, Slowly

While the Protestant mainline demonstrated early and eager interest, evangelical attentions were both sparse and mixed.2 Lewis’s first review came in 1936 from the Presbyterian Guardian for The Pilgrim’s Regress. While praising aspects of the novel, the reviewer expressed concern over Lewis’s high ecclesiology, owing to the book’s references to “Mother Kirk,” and misidentified Lewis as a Catholic—humorous because contemporary Catholics criticized Lewis for exactly the opposite concern.

As Noll notes, after this single review it was crickets for Lewis among the evangelical press for seven years.

In 1943, Screwtape raised eyebrows but not many. The Christian Herald gave it a few approving lines, along with his other novels as they came out. Same with The Case for Christianity, which Moody Monthly gave a mixed review at the end of 1943. Even after Screwtape, however, most of the engagement Lewis received came from critical, conservative Presbyterians.

These reviewers showed no interest in Lewis’s fiction. Rather, they had various theological bones to pick with his doctrinal books. They thought, for instance, that Lewis underplayed the effects of the Fall, that he “misunderstood the creator-creature relationship,” and that his appeal to natural law was misguided. (Ironically, the Catholics loved Lewis for that appeal. Can’t win ’em all.) Westminster heavyweight Cornelius Van Til derisively referred to Lewis’s position as “the gospel according to St. Lewis,” as opposed to the real thing.

To Noll’s point about Lewis’s reputation, historically speaking, what’s fascinating is that these unhappy Presbyterians represent, in Noll’s words, “the only evangelical Protestants in the 1940s to engage with Lewis at any depth.”

Acceptance, even enthusiasm, began to ferment, however, slowly bubbling up, especially from Wheaton College outside Chicago, Illinois. Professor Clyde Kilby became a booster, as did Wheaton sophomore Elizabeth Howard, better known by her married name Elliot (recently written about in depth by Lucy S. R. Austen).

Howard’s private praise of Screwtape (“clever”) and Perelandra (“tremendous”) to the family who edited the Sunday School Times eventually garnered Lewis a favorable hearing in the paper. From humble and stumbling beginnings Lewis’s reputation grew. As Noll points out, this lagging acceptance reflects a cultural shift underway among America’s conservative Protestants. In fact, one of the most intriguing aspects of C.S. Lewis in America is how Noll uses the various receptions of Lewis to mark the cultural evolution in the U.S. between the 1930s and ’40s.

Index of Cultural Evolution

The Catholic response, for instance, demonstrates a growing lay movement engaging in American public life before the Second Vatican Council, one with an ecumenical outlook. The fact that Sheed & Ward, a Catholic publisher, was the first to bring Lewis’s nonacademic work to an American audience is telling on this point. Pilgrim’s Regress wrestled with philosophical aspects of modernity; the fact that it came from an Anglican was incidental to its usefulness to Catholics, or Christians of whatever stripe.

The willingness among Catholics to circle around Lewis with mainline Protestants and eventually late-comer evangelicals, also reflects the growing secularity of the period, as Christians were increasingly apt to soften distinctives and think of themselves as “mere” Christians, allowing both a publicly facing faith and privately practiced version with solidarity in the public sphere and differences at the altar rail.

“A text, just like existence itself, cannot exist without conditions,” says Eugene Vodolazkin in his novel, Solovyov and Larionov. The history of Lewis’s reception from 1935 through 1947 underscores this point in fascinating ways. Reviewers saw Lewis indirectly addressing Nazism in both Out of the Silent Planet and The Abolition of Man, published in the U.S. in 1943 and 1947, respectively. Reading under different conditions, modern readers likely spy other threats in Lewis’s characters and arguments.

But encountering Lewis in his own time through the eyes of his first readers tells us something valuable beyond Lewis himself. It sheds light on the lives and concerns of those first readers and the world they inhabited. Texts exist with conditions; the conditions of America before the second half of the twentieth century reflect anxiety about increased secularity, relativism, and atheism, all of which Lewis addressed in one way or another.

Though cynical, Alastair Cooke’s assessment holds: Lewis was, by his readers, “pressed into making a career of reassurance.” And once Screwtape found its audience Lewis’s American publisher, Macmillan, was quick to facilitate. To the ongoing delight of both publishers and readers, the surprise is that Lewis’s response to the exigencies of his day remains interesting and adaptable to the present.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Lewis wrote Mere Christianity (1952), his most famous work alongside Screwtape and the Narnia series, by compiling and expanding three books published in this period: The Case for Christianity/Broadcast Talks, Christian Behaviour, and Beyond Personality.

Some fundamentalists outright doubted the sincerity of Lewis’s Christianity, as evidenced by the apocryphal story about Bob Jones II meeting Lewis and saying in spite of his assumptions, “That man smokes a pipe . . . and that man drinks liquor . . . but I do believe he is a Christian.”

It would have been interesting to include Fundamentalist Christian American views of Lewis. I grew up closely adjacent to Fundamentalism - never totally immersed because my parents were far too moderate. But growing up in that milieu, outsiders to our family made us children feel very guilty for reading even Christian fantasy authors like Lewis and Tolkien, much less secular fairy tales. To these people, the presence of magic in a book automatically made it demonic and its author must perforce also be Satanic, no matter the author's own stated faith.

'Out of the Silent Planet' is one of my favorite Lewis novels, next to 'Till We Have Faces'. Lewis perfectly captures the tone of the great early science fiction authors like Verne and Wells, and tips the genre on its head to make some profound statements about the impact of the Fall and the Incarnation on the created universe without ever losing the sense of curious wonder that made early science fiction novels literary classics. While the two successive Space Trilogy novels also have profound statements to make, Lewis makes the mistake of letting the message drive the narrative rather than vice versa, making them lesser works, though still well worth reading.

When the Narnia films came out in Germany the press warned their readers that this is the work of a Christian (fundamentalism! Danger!) and might include Christian symbolism -- as an American who was transported by Narnia as a kid I was outraged and frustrated at this concerted effort to destroy such a great work if fantasy before German kids could even get to know it.

This excellent article reminded me that Lewis originally known and controversial as a religious thinker and now I think that’s what stodgy German critics were thinking of.

It was too bad. Not only Narnia has so much to offer but his Christian philosophy works too. Thanks for this review I didn’t know how he was received in Ameriprise to Narnia.