Unraveling Narnia’s Genetic Code

C.S. Lewis’s Foreign Parts: Reviewing ‘East of the Wardrobe’ by Warwick Ball

If you’ve read any books in C.S. Lewis’s beloved Chronicles of Narnia series, you’re probably aware of the wild mashup of ideas, scenes, and characters that comprise the stories: fauns, dwarfs, talking animals, Fathers Christmas and Time, giants, and more. How did all those disparate elements come together—and where did they all come from?

To the extent we think about the question, the answer likely involves random bits of European myths and fairytales. The hodgepodge always bothered his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, who took far more care with his Lord of the Rings source material. I suspect the purist Tolkien would be bothered all the more to realize how far afield Lewis ventured for his stories.

Where Do Ideas Come From?

For his part, Lewis tended to push off questions about the sources of his creativity or feign ignorance. “Making up is a very mysterious thing,” he explained to Radio Times readers in 1960, several years after the Narnia books were finished. “When you ‘have an idea’ could you tell anyone exactly how you thought of it?”

He described his process. All seven books “began with seeing pictures in my head,” he said. But then he muddied the water:

A man writing a story is too excited about the story itself to sit back and notice how he is doing it. In fact that might stop the works. . . . And afterwards, when the story is finished, he has forgotten a good deal of what writing it was like. . . . So you see that, in a sense, I know very little about how this story was born.

Lewis had pleaded ignorance before. “Facts and influences and even turns of expression find a lodging in a man’s mind, he scarcely remembers how,” he said in his preface to Allegory of Love in 1936.

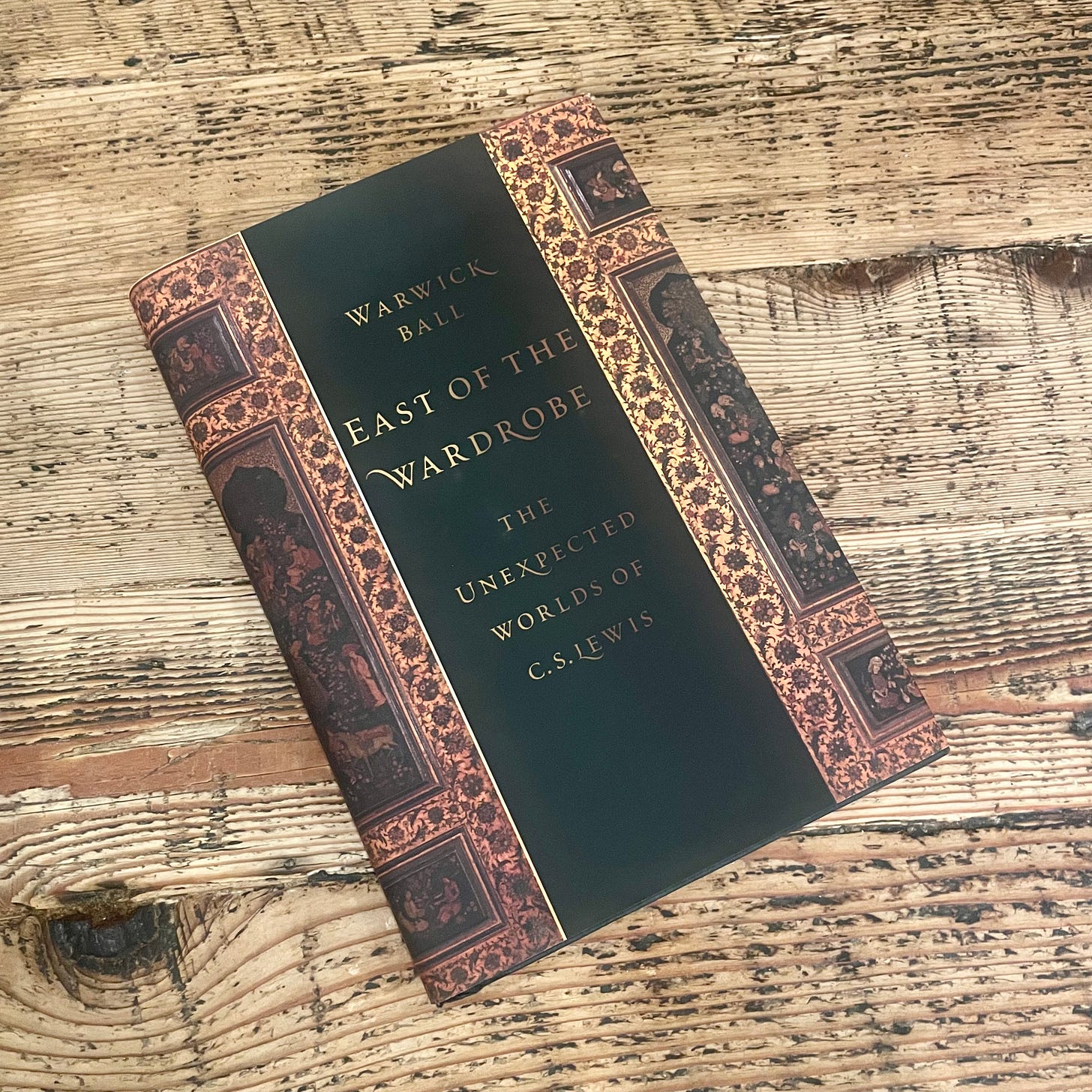

No one faults the magician for keeping the secrets to the trick, of course. But that hasn’t—and doesn’t—stop people from trying to crack the code themselves. Over the years many Narnia fans and Lewis scholars have leapt to the task. Among the most striking of recent attempts? Warwick Ball’s East of the Wardrobe: The Unexpected Worlds of C.S. Lewis.

Looking Eastward

Ball is a Near Eastern archeologist by profession. “I have,” he explains,

lived, worked, and travelled extensively throughout the lands of “the East” from the Mediterranean to China in the course of my work over the past fifty years or so. . . . An archaeological approach, together with an intimate knowledge of “the East,” has meant that it is possible to pick up on aspects [of the Narnia stories] that others might have missed.

That’s a little odd, no? Lewis traveled very little. He was injured on the front in the Great War and visited Greece late in life. Otherwise, he was mostly stationary—unless we’re talking about his imaginative life. As a reader, Lewis ranged all over creation, all through time, in and out of epics, myths, and philosophies.

As Ball demonstrates, Lewis’s mental adventures encompassed images, themes, and traditions of the geographic and cultural East—most of which he gathered from his extensive reading, though some came from conversations with travelers and other experts. Encountered over decades, these inputs and impressions served as the largely overlooked and understudied raw ingredients for the Narnia stories.

Consider The Magician’s Nephew. At the very moment Digory—standing in an Edenic, mountaintop garden—contemplates the forbidden act of taking a magical apple for himself, he looks up.

There, on a branch above his head, a wonderful bird was roosting. I say “roosting” because it seemed almost asleep; perhaps not quite. The tiniest slit of one eye was open. It was larger than an eagle, its breast saffron, its head crested with scarlet, and its tail purple.

The same bird and tree reappears in The Last Battle, where at the center of the garden it sits “in a tree and look[s] down upon them all.” A bird in a tree is not remarkable, but an all-seeing bird atop the central tree in a paradisiacal garden? We could identify the tree as the Tree of Life from the Genesis, and we’d be right about that. But there’s more.

From Persia, with Love

Other eastern traditions beside Genesis utilize magical trees. One, as Ball points out, features a bird. “This,” says Ball, “appears to be the Saēna Tree of Zoroastrian tradition: the Tree of all Trees, the Tree of all Seeds, where rests the great mythical bird, the Senmurv. The Senmurv is the great all-seeing, all-knowing bird of Persian mythology.” Islam later adapted the story from the Persians.

Notably, the Saēna Tree was considered the Tree of Life, imbued with healing powers (same as Digory’s tree), and the bird was imagined to hold all in its gaze (same as Digory’s bird). If it walks like the Senmurv and quacks like the Senmurv. . . .

Does this mean that Lewis was secretly a Zoroastrian? It’s a silly question but worth raising and dismissing early on because some well-meaning readers take The Chronicles as para-religious texts, given all their Christian symbolism. If so, we might as well say Lewis was also secretly Manichean and Sufi—Ball points to plenty of elements plucked from those traditions as well. Better to say Lewis was simply employing resonant images from his reading to likewise resonate with his readers.

In some cases he borrowed more than images. Robert Byron’s 1937 Road to Oxiana contained some of the most popular travel writing of the period. One episode provided Lewis the basic plot of The Last Battle. An Afghan legend, related by Byron, tells of a jackal who convinces a donkey to don a lion’s skin and lord it over the other animals as a pretend king. Lewis swapped the jackal for ape, but even that had precedent. The Sufi mystic Rumi wrote about the “tricksy ape,” and Lewis presents apes as dishonest in The Horse and His Boy. The creature’s inherent mendaciousness is right there in his name: Shift.

What’s in a Name?

Recently Michael Ward has shown that Lewis structured aspects of the Narnia tales around the Ptolemaic and Medieval view of the cosmos, with each of the seven books corresponding to the sun, moon, and five anciently known planets. Similarly, the twelfth-century Persian poet Nizami of Ganja, whose lyrics found their way into English in the decades before Lewis wrote the Narnia stories, employed the planets in his Haft Paykar, or The Seven Beauties. But that is just the beginning of the similarities.

At one point Nizami’s hero Bahram disappears into a cave while hunting a mysterious onager (wild donkey), just as Peter, Edmund, Susan, and Lucy disappear into a wardrobe while hunting a white stag at the end of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. And in the opening section of Haft Paykar, Nizami praises his patron, whose name was Aslan, by comparing him as a ruler to a lion!

Lewis would have come across this connection in other places as well. The name Aslan means lion in Turkish, but, as Ball points out, the typical form is actually Arslan, which

would have been inappropriate for a children’s book, sounding as it does slightly rude (reading out “arse” in children’s bedtime stories would have resulted in uncontrollable giggles—although Lewis himself was not above such bawdy humour), so the more correct Turkish form would not have been the origin for Lewis’s greatest character.

In James Morier’s 1895 novel The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan, informed by the author’s travels through Iran, the hero runs across a Turkoman chief named Aslan Sultan, or chief lion. As with Nizami’s prefatory pun, Morier’s story offered Lewis the right form of the name with its leonine association. Heightening the connection, Morier also recounts another version of the Afghan donkey-in-lion-skin story, only in his telling the skin is a tiger’s.

Nectar from Eastern Flowers

The strength of Ball’s study lies in his own vast awareness of Eastern stories and elements. He, for instance, complicates even simple borrowings like Lewis’s use of Father Time by showing how his depiction as a giant who awakens at the end of time is drawn from the Zoroastrian story of the giant Karshasp who similarly awakens at the eschaton.

These and a hundred more connections came from a lifetime of Lewis’s reading. Some of these links are speculative and conjectural, but others are easily spotted in books Lewis was known to have read, such as The Arabian Nights, which not only provided the ancestry of the White Witch Jadis, but several other plot points, including Digory’s apple, Shasta’s royal lineage, the Witch’s living statuary, and Lewis’s depictions of the Calormen.

Eastern travel writing also provided the origins of the Marsh-wiggles, as well as the raw ingredients for Jadis’s destroyed city of Charn with its echoes of Petra, Persepolis, and Palmyra.

What do we make of all this borrowing and appropriation? Ball favorably compares Lewis to a literary magpie, collecting bits of this and that. Following Seneca, however, I prefer to see him as a literary bee distilling and transforming the nectar from a million flowers into his own singular concoction. “We also,” explained Seneca,

ought to copy the bees, and sift whatever we have gathered from a varied course of reading . . . then, by applying the supervising care with which our nature has endowed us . . . we could so blend those several flavors into one delicious compound that, even though it betrays its origin, yet it nevertheless is clearly a different thing from that whence it came.

Lewis said his creative process started with pictures in his mind’s eye. What Ball convincingly demonstrates is that the shapes and colors of those images were informed by decades of voracious reading far beyond Western horizons.

Ball’s East of the Wardrobe works on at least two levels: If you’re looking for a study in creative adaptation, it provides dozens of fascinating examples and rewards reading with a pen in hand. If, on the other hand, you’re looking to go further up and further in to Narnia and the vast world of its creation, East of the Wardrobe offers a rare and illuminating perspective sure to expand the scope of one’s appreciation and the reach of one’s imagination.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Readers of Spenser's Faerie Queene, a great favorite of Lewis's, will find a likely origin of his method in the Narnian books. Spenser freely mingles Classical and Northern European mythology and folklore, and elements of Western history. As for the Calormenes, they are "Paynims," idolaters.

Lewis writes enjoyably about Spenser in Selected Literary Essays ("On Reading 'The Faerie Queene'" is a good one to start with), a portion of English Literature in the 16th Century, and, for last, Spenser's Images of Life.

I'm afraid that, where the FQ is taught at all any more, teachers burden the student with bosh about "critical lenses" of postcolonialism, gender issues (Britomart!), etc. and allusions by Spenser to contemporary politics. For most readers these are not good ways to make acquaintance with this poem, which should be read largely for pleasure. Anyway that's what I aimed at when I taught Book I, using the very reader-friendly edition published by Canon Press, Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves. There is wisdom there that doesn't require the tools of today's scholarship to perceive.

Lewis said ideally one would meet the FQ as a young person in a copiously illustrated edition. Get hold of the Dover paperback of Walter Crane's drawings for the FQ and enjoy them as you read Spenser.

This info is kind of a relief to me, actually. When I moved to London in my 20's to work among "people of the East" (the East End of London, actually, but also originally much much further East), I reread both Narnia, and I remember being stunned at the glimpses of culture I was encountering in real life, especially in the Horse and His Boy. But I was also disquieted that it seemed like most of that cultural/literary borrowing got applied to Narnia's "villains." I'm rather happy for the revelation that some of those Eastern literary devices, etc, were also woven into the Narnian Paradise and other places. (And I did know about the name Aslan. That always helped!)