All the Authors We Forgot Along the Way

C.S. Lewis’s Bad Prediction, Finding Zora, Losing Ursula, Saving Gatsby, and What Publishers Can Do

C.S. Lewis never imagined the lasting influence he would have. “After I’ve been dead five years,” he told his friend Owen Barfield, “no one will read anything I’ve written.” Proving the old don wrong, this year marks the sixtieth year of his passing, and Lewis is read today perhaps more than ever.

Still, it’s a reasonable hunch. Books are not immortal. They rarely live beyond the generation of their author and earliest readers. Usually, they die much sooner than that.

The blood and breath of books are the thoughts and words of readers, the people who animate the pages once an author has let them go. Almost inevitably readers stop thinking and talking about them. When that happens, they fall out of mind and die. Just scan the winners and finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction or the No. 1 New York Times bestsellers through the years and see how many names you recognize.

Only a handful of special books bridge the generations and find readers to breathe life between their leaves one decade to the next, books like—despite his humble self-assessment—Lewis’s. But it didn’t have to go that way.

Their Eyes Were Reading Something Else

I recently read Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God as part of my classic novel goal for August. The novel is now a mainstay for high-schoolers and college students around the country and regularly hits lists of greatest American or English-language novels.

Today, it’s sold millions of copies but went out of print shortly after it was first published in 1937. None of Hurston’s books stayed in print long, and she was mostly forgotten even before she passed away in 1960.

So how do we know about her work today? Two words: Alice Walker. The Pulitzer-winning poet and novelist had read a short story of Hurston’s and wanted to know more. She soon became a champion for Hurston’s work and helped spark a revival of interest in her novels and short stories in the 1970s. Then, as University of Utah dean of humanities Hollis Robbins points out, Henry Louis Gates Jr. continued the effort, publishing most recently an acclaimed collection of Hurston’s nonfiction, You Don’t Know Us Negroes.

We read Hurston today largely because Walker’s advocacy gave her a second chance and scholars like Gates joined in the effort. Not every forgotten author gets that.

Early Success, No Guarantee

Unlike Hurston, Ursula Parrott had significant early success. Her Jazz Age novel, Ex-Wife, sold over a hundred thousand copies after it was published in 1929. What’s more, says Parrott biographer Marsha Gordon, “It was translated into multiple languages and reprinted in paperback editions through the late 1940s.”

And yet I bet most of us hadn’t heard of Parrott or Ex-Wife until this moment. Speaking solely for myself, nope. The novel follows the life of a Manhattan divorcée struggling to make her life work as a single woman—a struggle full of sexual risk, financial difficulty, alcohol dependency, and other challenges Parrott knew personally and which seem to have got the better of her in later years.

She died penniless in 1957 after a stint of homelessness, forgotten by most but the fans of Walter Winchell’s syndicated gossip column—likely not members of the literati.

Gordon compares the trajectory of Parrott and her successful novel with that of a book that initially sold just a quarter the copies. Parrott and Ex-Wife went from popular to obscure. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, on the other hand, went from meh to marvelous! What’s the difference?

Sex Sells, Except When It Doesn’t

One partial answer for Parrott’s decline relative to Fitzgerald’s rise is her sex. Gordon notes that books by women tended to get labeled as romance and thus marginalized. Meanwhile, despite unmistakable features of the story, there has been, she says, “what can only be described as a collective refusal to categorize The Great Gatsby as a romance novel. . . .” This bears directly on the subsequent success of Gatsby compared to Ex-Wife.

Fitzgerald died a bit of a washout in 1940. While his initial novels, This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and the Damned, sold like crazy, Gatsby was a letdown. What’s more his entire catalogue had long-since cooled by the day of his demise. “The grand total of his royalties at the time of his death,” says Cristina Hartmann, “was $13.” There was no reason in 1940 to imagine The Great Gatsby would rise to its current stature. Nevertheless, as Fitzgerald died, Gatsby was reborn.

During World War II, the Victory Book Campaign solicited book donations for American servicemen serving overseas. Books would boost morale through both entertainment and reminding the soldiers, sailors, and airmen what they were fighting for. Millions of books were donated. Publishers included cheap backlist paperbacks like Gatsby; it proved a second lease on life.

Meanwhile, “books . . . primarily intended for children or women” were discouraged. Gordon notes that in a list of “Don’ts for Donors” Parrott was mentioned by name as someone whose books did not warrant inclusion.

We can’t understate the impact WWII had on Fitzgerald’s posthumous fortunes. Selected for inclusion in the Armed Services Editions program, more than 150,000 copies of The Great Gatsby traded hands. “Authors whose books were selected as ASEs were rewarded with a loyal readership of millions of men,” writes Molly Guptill Manning in When Books Went to War.

Word spread quickly about the titles that were perennial favorites, even reaching the home front. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, which was written in 1925, was considered a failure during Fitzgerald’s life-time. But when this book was printed as an ASE in October 1945, it won the hearts of an army of men. Their praise reverberated back home, and The Great Gatsby was rescued from obscurity and has since become an American literary classic.

Had Gatsby been written by a woman and shunted off to romance, that would have likely never happened.

Parrott is far from alone in this disregard. In his study of forgotten authors, Christopher Fowler dedicates a chapter to “forgotten queens of suspense”—women authors who never received their due for pioneering psychological thrillers. Of course, as Fowler also notes, there are other factors at play.

Saving Gatsby

Authors who fail to convincingly self-promote have tended to see more decline when compared to those who advocate for their books. According to Fowler’s research, those who undervalue their work or avoid the public eye, or whose genres are either overlooked or whose subjects don’t age well have found readerly attentions fleeting.

Proper management also plays a role. “It is true that Parrott did not publish during the last, difficult decade of her life,” admits Gordon. “After a series of public scandals, missed deadlines, ongoing battles with alcohol and financial missteps, she tried to write herself back into literary society, to no avail.” Hurston had similar troubles.

But even this wasn’t enough to hit the dimmer switch. Beyond the surge of popularity aided by Gatsby’s circulation among U.S. servicemen, Gordon points another factor: posthumous critical support. Fitzgerald and literary critic Edmund Wilson had been friends since college, and Wilson helped Gatsby find its way back into print in 1941, along with several of Fitzgerald’s short stories and an unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon.

Other critics jumped aboard to praise Gatsby’s genius: Lionel Trilling, Malcolm Cowley, William Troy, and others. These critics, says Gordon, made all the difference.

After Trilling, a parade of writers took up Gatsby’s cause, praising it for precisely the same traits that might also have been found in Ex-Wife, had anyone bothered to look: its use of contemporary language, its critique of hedonistic behavior, its rich attention to period detail and its depressing portrayal of aimless, unmoored characters trying and failing to find meaning in modern America. . . . The real difference, in my view, is that Parrott had nobody to tend to her legacy—no Trilling or Wilson or Cowley in her corner to bring her writings back into circulation or make a case for her genius or her novel’s importance.

Hurston’s decline was much the same. It’s possible her sex worked against her, compared to rivals such as Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison. But it seems truer to say Hurston’s idiosyncratic focus distanced her from the voices in the critical establishment that would champion her work. She was happily out of step, but she paid a price for her independence—at least at the time.

If the blood and breath of books are the thoughts and words of readers, lasting books require advocates to bring them into the public’s consciousness and keep them there. Fitzgerald had that. Eventually, so did Hurston. Parrott, no.

But it’s more than critics who do this work.

Don’t Forget the Publishers

I often think of this line from economist Israel M. Kirzner’s 1973 treatise, Competition and Entrepreneurship:

Because the participants in [the] market are less than omniscient, there are likely to exist, at any given time, a multitude of opportunities that have not yet been taken advantage of. . . . To discover these unexploited opportunities requires alertness.

Unevenly distributed knowledge creates the drama of business, the adventure of enterprise. Why? What you know that I don’t is the start of a business plan.

Much to the bafflement of outsiders—and many insiders—publishing is fundamentally a business concerned with profitably trading in the cultural product called books. The relative success of a publishing program depends on publishers and editors being alert to the “multitude of opportunities that have not yet been taken advantage of.”

A forgotten author can present such an opportunity. Have you, for instance, ever heard of Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis and his 1881 Portuguese classic The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas? Neither had I. But Dave Eggers read a translation in 2019 and loved it. If Eggers would stump for the book, a publisher might have a shot bringing it back from the dead.

Lo and behold! In 2020 Penguin republished the book in translation with a foreword from Eggers, who also helped promote it. “These unexploited opportunities require alertness.“ Similarly, Virago Books and the Booker Prize are currently attempting to goose the memory of forgotten author Elizabeth Mavor, shortlisted for the prize in 1973. I wish them luck.

This alertness for opportunity is a critical component of Fitzgerald’s rebound in the forties and Hurston’s in the seventies. Thanks to the factors we’ve already described, publishers spotted an opportunity and assumed the risk. And this takes me back to C.S. Lewis, who wrongly assumed his books would drift into obscurity.

Why We Know Jack

Given Lewis’s current status as anything but forgotten and obscure, it might seem strange to imagine such a fate. But oblivion is the usual, so we should actually be surprised by his staying power.

When he died, Lewis possessed what we would today call a successful brand and a decently managed literary enterprise. But, critically, he also had advocates—in his case, his secretary Walter Hooper, who managed the posthumous publication of his books, and legions of fans for his fiction and religious work.

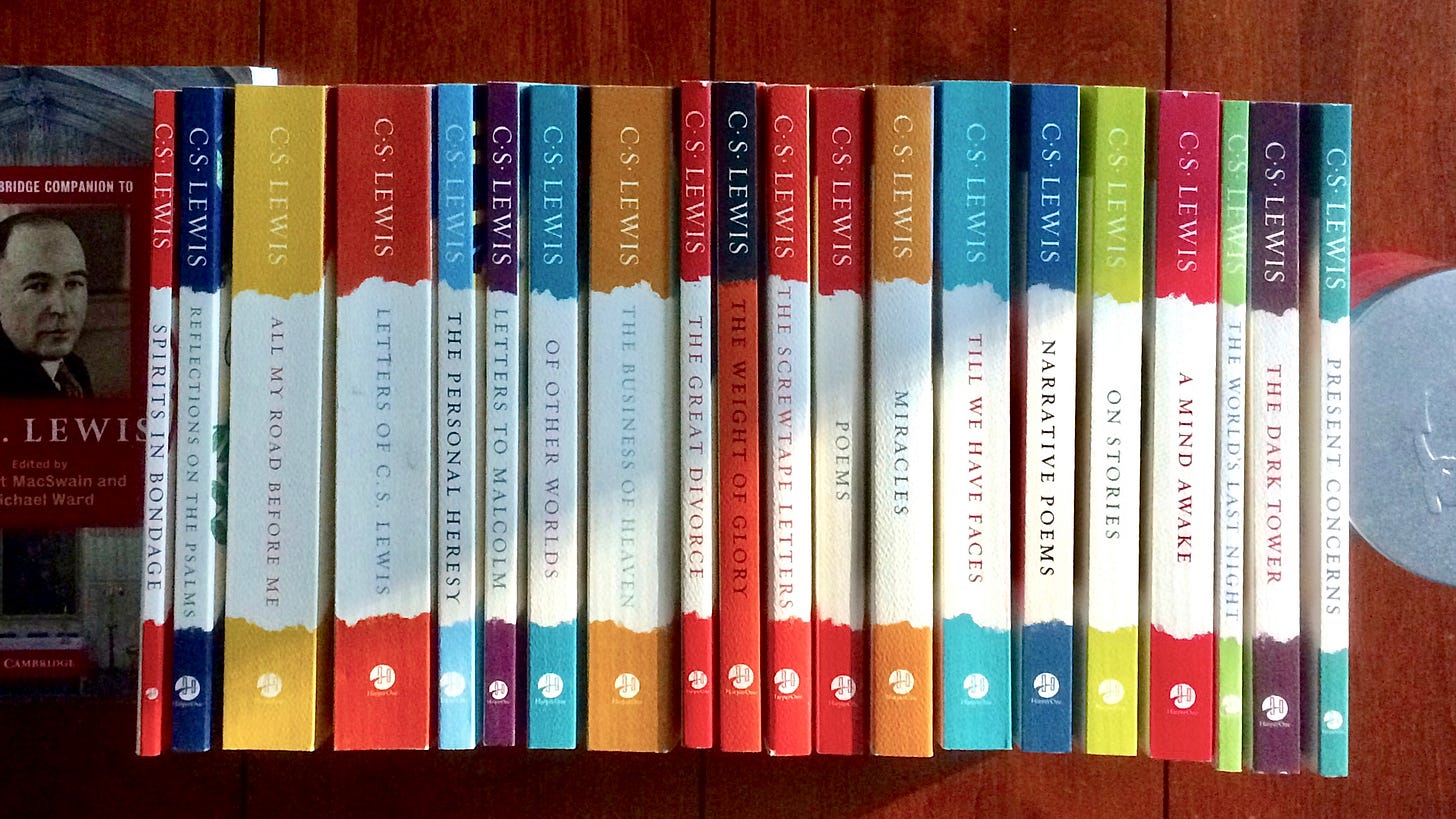

That kept his legacy humming through the seventies and eighties. But the majority of his books were published by a handful of random publishers—Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Touchstone (Simon & Schuster), Eerdmans, Macmillan, and others—and many of his books, especially the academic titles, weren’t available at all. There was no concerted effort to elevate Lewis’s work.

In stepped HarperCollins in the early aughts. In March 2001, the publisher announced an exclusive, worldwide deal with the C.S. Lewis Company, an outgrowth of the author’s literary estate. Stephen Hanselman, then the publisher of HarperSanFrancisco, went into gear designing a unified brand look for Lewis’s packaging, expanding the company’s line of books, and creating new offerings, including the daily Lewis reader, A Year with C.S. Lewis (a format Hanselman would use again with Ryan Holliday, The Daily Stoic).

Despite anxiety among evangelical fans that the secular publisher would somehow dilute Lewis’s Christianity, the concerted editorial, marketing, and merchandizing efforts did nothing but expand Lewis’s reach and ensure his glum prediction would prove spectacularly false.

A decade after the deal, Lewis had never been bigger. The Chronicles of Narnia remained the biggest books on the list, but repackaged classics like The Screwtape Letters and Mere Christianity were selling 150,000 units a year. “I would say in the last 10 years, C.S. Lewis has sold more books than any other 10-year span since he started publishing,” said Harper executive editor Mickey Maudlin. “He’s not only not declining, he is in his sweet spot.”

That speaks not only to the power of Lewis’s writing, but more besides: No successful author shoulders his or her legacy alone. It’s held aloft by a host of readers, critics, advocates, and publishers—without whom the authors we love would simply, inevitably disappear.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post:

We might also say that Evangelicals saved Lewis. Wheaton College, the Notre Dame of Evangelicalism, houses a good bit of his work and artifacts, along with other early/mid-century Brits like Sayers and Tolkien. I discovered Lewis as a student at Gordon-Conwell, a Reformed, well, non-denominational (but definitely Reformed) seminary.

PS: I've always found that a Evangelical-Lewis connection a bit ironic given his prominent emphasis of the Ransom Theory of the atonement.

Some writers are so ahead of their time and talented in prose it takes decades for the masses to catch up to their immense talent.