When the Rules No Longer Apply

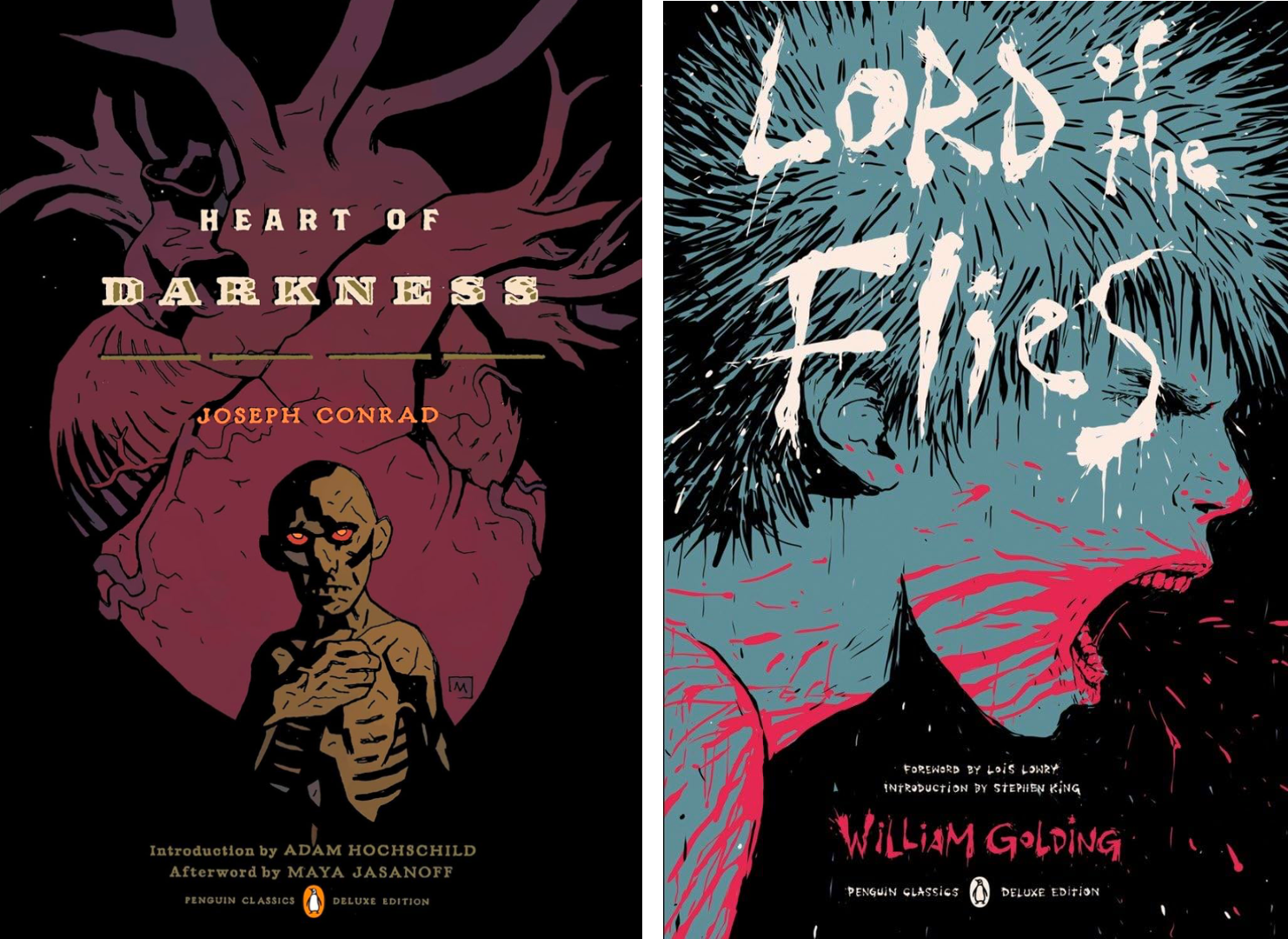

Reviewing Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ and William Golding’s ‘Lord of the Flies’

What happens when the rules no longer apply? That question nudged me toward Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. I read them back-to-back over a couple of days last week; as I closed first, I opened the second.

Both explore the darker side of human nature—if such a thing even exists; I’m not always sure it does. Thankfully, human history is less ambiguous; riffle its pages, and you’ll find moments that have drawn people toward the good, the elevated, the praiseworthy, and others that have summoned terrors.

Conrad and Golding are interested in the latter: What happens when constraints slip, when civilization recedes, and we discover what we are without them?

A Soul Gone Mad

Heart of Darkness, published in 1902, came during the height of the Scramble for Africa, as European powers invaded and sliced up the continent. Golding’s novel appeared half a century later, in 1954, darkened by the shadow of two world wars. The difference in mood is palpable. Lord of the Flies emerged from a world that had seen the worst of what humans can do to one another—not in far-off lands, but in the heart of Europe.

Both stories ask what happens when law disappears. I don’t mean mere legislation, statutes, or codes. Golding once said Lord of the Flies was about what happens when people find themselves without law, by which he meant the full range of external constraints to which we willingly submit: norms, expectations, shared assumptions, what Jonathan Rauch calls “hidden law.”

Conrad plays with the same idea. There’s a moment where the narrator, Charles Marlow, reflects on the small, civilizing nudges of life at home: the neighbors, the policeman, the fear of reprisal or scandal. Take those away, and we fall back on whatever inner reserves we have left—if we have any at all.

“These little things make all the great difference,” Conrad writes. “When they are gone, you must fall back upon your own innate strength, upon your own capacity for faithfulness.” After briefly thumbing those aforementioned pages of human history, we know that mileage may vary.

Both Marlow and Conrad’s antagonist, Kurtz, are drawn away from the tethering norms of their homeland into the Congo—where Kurtz cracks. “His soul was mad,” says Marlow. “Being alone in the wilderness, it had looked within itself, and, by heavens! I tell you, it had gone mad.”

Willingly Scrapping the Rules

You get the sense that Kurtz’s descent was unintentional, accidental; separated from the constraints of civilization, he succumbed to his own demons. The boys in Golding’s Lord of the Flies are different. Ralph, Piggy, Jack, Simon, Roger, and the rest are stranded on an island by chance, true, but what happens next is intentional.

They know there’s an expectation to hold it together. “We’re not savages,” says Piggy. “We’re English.” They even codify it. The conch shell serves as more than a call to assembly; it’s a symbol of who has the right to speak. It marks the boys’ mutual agreement to remain civilized. And when it’s dashed to pieces—when Jack and his tribe destroy it—Piggy dies. The symbol shatters, and with it a person is shattered, too, along with any remaining illusions.

“Bollocks to the rules!” says Jack. “We’re strong,” a claim he backs with force.

Violence plays differently in the two stories, and I can’t help but think this is informed by Lord of the Flies’ later composition—one that had seen the devastation and human cruelty of the two world wars, especially the rise of the Nazis.

In Conrad, violence is often incidental, offhand. Marlow doesn’t even realize he’s under attack until someone points out that the flying sticks whizzing overhead are arrows. When he finally gets a chance to confront Kurtz alone, the moment fizzles; even the idea that he might kill Kurtz passes with a sigh. There’s a strange anticlimax to the violence, a kind of shrug, as if it’s all for nothing and meaningless anyway.

Not so in Lord of the Flies. There, the threat builds with every chapter. What starts as playground jockeying for position whips and builds into a literal firestorm of terror. Simon is killed in a moment of frenzy and madness, Piggy as a victim of contempt, and Ralph is hunted like an animal.

Whither Human Nature?

The two books diverge sharply in their endings. Conrad’s closes with a lie, Marlow choosing to shield Kurtz’s fiancée from the truth. Even after all he’s seen, even after observing Kurtz consumed by his own depravity, he withholds the truth. Marlow lets her remember Kurtz as noble; we’d rather deceive ourselves than reckon with what people can become—what we can become.

In Golding’s world the boys are rescued from the island but not from themselves. When a naval officer arrives on the shore, they all collapse in tears—including the monsters—undone by their own deeds. And that undoing offers the slimmest chance of hope; once we’re undone, there’s a chance to repent. That’s better than a lie.

Some might point to a real-life Lord of the Flies story in which a group of stranded boys pulled together, cooperated, and were ultimately rescued unharmed. It’s often held up as proof that Golding got it wrong. And if we’re comparing outcomes—imaginary boys killing each other versus real boys surviving in solidarity—we might be tempted to agree.

But this isn’t a contest between competing narratives where the happier, or even actual, ending wins. The point is not whether Golding’s story always happens, but that it can happen—and does. Same with Conrad’s. After all, don’t forget those history books. But, no, go ahead and put that aside as well: The real plausibility question is one only the individual reader can answer.

Can we imagine ourselves in such circumstances? What kind of person are you without the neighbors, the policeman, the fear of reprisal or scandal? The modest cover price is a small fee for two thought experiments as exquisitely rendered as this pair of enduring classics.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please share it with a friend. Or an enemy. I’m not choosy.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe. It’s free and will boost both your IQ and EQ inestimably!

Thanks for that, Joel. Both great books, read them years ago.

As to, “What happens when constraints slip, when civilization recedes, and we discover what we are without them?”

Well, I think of people like Luigi Mangione, Antifa, BLM mobs, those sorts. They’re all mostly young folk. Young people are being programmed to believe that violence is acceptable if the person dishing it out is ‘right.’ Young people are being programmed to believe that they can do anything, and be whatever they want, simply by saying they are that thing.

The movie, Apocalypse Now borrows one of the themes of The Heart of Darkness. The Congo’s Kurtz descends into savagery in his pursuit of ivory, becoming the most ‘successful’ ivory hunter. The Vietnam War’s Kurtz, descends into savagery in his pursuit of dead Viet Cong. Both Kurtz’s also embody Jack’s pronouncement, “Bollocks to the rules! We’re strong.”

Apocalypse’s Kurtz adopts the rules (savagery) of the communists Viet Cong, taking names and heads. He becomes better at the madness and mayhem of war than the Cong and any of the perfumed princes of the Pentagon.

All three of these stories (The Lord of the Flies, Heart of Darkness, Apocalypse NOw) mine this rich and important (to understand) vein.

Others say, Law is our Fate;

Others say, Law is our State;

Others say, others say

Law is no more,

Law has gone away.

And always the loud angry crowd,

Very angry and very loud,

Law is We,

And always the soft idiot softly Me.

W.H. Auden - from "Law Like Love"