Bookish Diversions: Reading as Help for Living

Making Decisions, Novels as Practice, Theaters for Self-Reflection, Dark Books, Measuring ‘Narrativeness,’ More

¶ Decisions, decisions! Steven Johnson’s 2018 book Farsighted presents a method for processing decisions—not the easy kind (cherry pie or apple?) but the tough, Russ Roberts–y, wild kind, with all the considerations and contingencies that spool out like thirty-seven balls of yarn rolling downhill. Do I:

marry Sally?

put Dad in the nursing home?

change a policy that affects my coworkers’ retirement?

move to Montreal?

chuck it all and go into the car-wash business with my cousin Earl?

Good luck!

Wild problems often involve simple, binary choices—yes or no—but they contain countless concerns and consequences. Sally, Dad, coworkers, Montreal, Earl: to one degree or another, the variables multiple as we consider them and ramify in ways we can’t fully corral.

To decide, says Johnson, we must manage to map the variables and then predict the outcomes. We’ll do so imperfectly, and we’ll get more wrong than right—whether the extent of our errors proves material or not. (The future ain’t easy, friends.)

One help in this fraught and feeble process? Surprisingly, Johnson suggests novels, pointing to George Eliot’s Middlemarch as his primary example. The tortured decisions with which Dorothea and Lydgate contend involve multiple dimensions and layers, and Eliot takes us inside their minds as they messily try mapping the variables and predicting their outcomes. Novels are for their readers, in other words, practice. “When we read those novels,” says Johnson, “we are not just entertaining ourselves; we are also rehearsing for our own real-world experiences.”

But the practice extends beyond personal considerations.

¶ Thinking across dimensions. I recently returned to Johnson’s Farsighted because Johnson did. In an essay here at Substack he mentioned reading a tweet in which Stripe CEO Patrick Collison recounted the experience of reading ten classic novels during the year:

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Middlemarch by George Eliot

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

Portrait of a Lady by Henry James

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann

Why would a Silicon Valley tech exec read these sorts of books? Collison admits skepticism about fiction’s power to improve our personal morality but says they can elevate our appreciation of intellectual excellence.

What about improving our understanding of human nature more broadly? “There is almost certainly some extent to which this argument is valid,” says Collison, “though I always wonder: do they help you better understand humanity, or better understand the kind of people who write books like these?”

I don’t know if novels help us better understand abstract humanity. But I’m convinced as theaters for self-reflection they do help us better understand ourselves and what we think about the world around us; that might generalize to the whole species, but it needn’t do so to be valuable for the individual reader.

Revisiting his argument in Farsighted, Johnson offers two explanations of why, one more obvious, the other less so. First, the obvious one:

Novels (and fictional narratives in general) [are] extensions of the human mind’s marvelous aptitude for building simulations of potential events. It’s something we do so effortlessly that we rarely stop to think about how nuanced a skill it really is: creatively projecting forward into our possible futures based on our previous experience of the world. Narratives of all sorts allow you to parachute into other simulated experiences, which ultimately give you more data for your own simulations. But novels, I would argue, give you the richest simulation of the interior life of other people’s experiences: you get a ringside view of all that emotional and cognitive action. . . . It seems fairly obvious to me that there is practical utility in running these simulations. We accumulate wisdom that we can apply to our own lives by watching other people live theirs.

But, says Johnson, great novelists can push us further, past the mere interiority of their characters’ mental and emotional experience. They can take us across the many dimensions a character’s thought process might travel, all of the external pressures and factors that could come to bear.

“They show us,” says Johnson,

how those private moments of emotional intensity are inevitably linked to a broader political context; how technological changes rippling through society can impact a marriage; how the chattering of small‑town gossip can weigh on one’s personal finances.

These and other dimensions form the texture of real-life decisions—which is why novelists who manage to thread all these beads can render depictions of life that resonate so deeply. Writers recruit our imagination, our hopes, our reticence, our problem-solving abilities, our moral frameworks—everything that makes up our cognitive toolkit—to inhabit the characters and worlds they build. As readers, we don’t simply observe their characters’ choices; we vicariously participate in them. We imagine how we would perform given the same variables, if barred one choice, if offered another. And as we orient ourselves within these fictional worlds, we find firmer footing in the real.

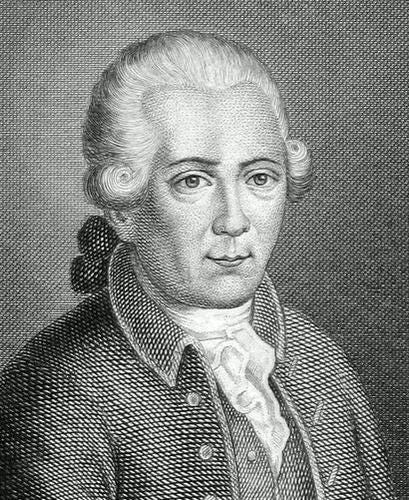

¶ Don’t rule out moral improvement. What about Collison’s doubts about the moral utility of fiction? He’s not alone in doubting its efficacy. “A book is like a mirror,” said German scientist and satirist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. “If a donkey looks in, you can’t expect an apostle to look out.” Expectations aside, can a book transform an ass into a saint? Maybe—because of a simple but intriguing dynamic.

Philosopher Martina Orlandi notes that participating in the life of a character (or several) in a story can “bypass rational reasoning,” making fiction “a useful tool for gaining insight into personal flaws.” I can’t speak for you, but if someone confronts me about my objectionable behavior, I often get defensive and marshal arguments for my innocence, even my righteousness. But a story sneaks the accusation around my defenses.

Because it’s another person (the character) I can be objective about what’s objectionable. At the same time, by participating in the simulation, I can come to acute moral awareness. It’s happened to me many, many times; in reading about others’ shortcomings, I’ve indirectly glimpsed my own.

Reading a story “doesn’t confront you with reasoning,” explains Orlandi,

but rather transports you into a narrative world, where you can temporarily mute your self-related beliefs and desires as you adopt a character’s perspective instead. This immersion could be what undercuts the defensiveness that rational criticism might trigger. It puts us, for a moment, on the same side as the person who would criticise us and makes it easier to see why. . . . Empathising with a character seems to lower our guard, essentially, making us more receptive to learning about ourselves.

Of course, if we’re determined to defend our righteousness, the donkey will renew its gaze. But if we’re open, a novel might nudge something better into view.

¶ Mentored by the classics. Part of the equation? How far we submit to the experience itself. A book is like any relationship: If we engage in order to judge, we’ll likely be worse for the experience. Instead, says Kittie Helmick, we should read both slowly and humbly—as if we have more learn than to offer.

“If the style or context of a great literary work does not suit our taste, perhaps the fault lies not with the literature,” she says. “As [Winnie the Pooh author] A. A. Milne said of The Wind in the Willows, ‘You don’t judge it; it judges you.’”

It’s possible our taste is deficient, our background knowledge incomplete. Or is that possibility new to us? Admitting the gap could be with us, not the book, offers another step toward moral improvement—no lighting-bolt insights required.

¶ A source of consolation. We can probably overstate the healing powers of books, but bibliotherapy has its practitioners and its grateful patients; educator Peter Leyland shares stories of successful sessions with his students. I tend to think same sort of openness and humility required for moral improvement through books is required for effective bibliotherapy, but we probably know from our own experience how consoling the right book can be.

Cody Delistraty describes how reading helped him navigate the death of his mother:

In reading . . . the apparent specialness of my grief began to wane. . . . The most intense kind of grief can feel unprecedented because, when it happens to us, within our own perception, it really is unprecedented (at least the first time). But countless works of history, literature, and philosophy have reckoned with grief.

The same can be said for making sense of the world on the other side of natural disasters, such as fire.

¶ Over to the dark side? Of course, if books can have this sort of positive effect on us, it’s probably fair—only honest, in fact—to say they can have negative effects too. A young man named Werther could tell you all about it, except he’s dead: suicide. What’s more, his fictional death supposedly led many flesh-and-blood readers to embrace the same fate; it’s been called the Werther Effect.

Like many supposed effects that acquire capital-letter names there are plenty of reasons to doubt the scope of the effect, but it’s worth considering. A thoughtful response on Werther:

As for the broader effect of being negatively influenced by a book, that’s not only possible, it’s even probable from time to time. If a book is, among its many other wonders, a means of conducting a relationship from afar, then surely we can all vouch for ideas we’ve received—ideas which have even haunted us—from both people and pages.

“At its most fundamental level, to read is to put our selves at risk, to make ourselves vulnerable by welcoming the presence of an other into our psychic space,” says Tara Isabella Burton in a fascinating piece for Aeon. “This can be a radically transformative experience, challenging us to reformulate our own self-understanding.” But that’s not the only possibility: At worst, says Burton, a book can arouse latent vices, such as violence, or leave us feeling threatened.

“That doesn’t mean we should . . . ban novels altogether,” she says. “Rather, it means respecting that the power of the novel lies precisely in the potential it has to destroy us.” Overstated? Perhaps, but Burton is getting at something important:

To acknowledge that textual narratives have as much capacity to be truly dangerous as they have to be truly illuminating is to acknowledge that books, like people, are not inherently moral or immoral. Only by respecting the potential of books to destroy us—terrifying as it might be—can we have an authentic faith in their ability to put us back together again.

¶ Measuring “narrativeness.” Given all these potentialities of literature, it might be tempting to regard the humanities as inherently more virtuous or somehow of greater benefit than the sciences. That would be a mistake. At the very least, it’s a false dichotomy; the sciences are a necessary part of the humanities. But the sciences aren’t sufficient to understand ourselves or the world; neither, for that matter, are Dickens and Dostoevsky.

Thankfully, Johnson can help us out again. In an endnote in Farsighted, he points to a concept from literary critic Gary Saul Morson called “narrativeness,” which describes how much a particular phenomenon requires a narrative to explain it.

“Although one could give a narrative explanation about the orbit of Mars,” says Morson, “it would be absurd to do so because Newton’s laws already allow one to derive its location at any point in time.” But what about Sally, Dad, my coworkers, Montreal, and Earl? Those orbits are different. Locating Mars has “zero narrativeness,” says Morson, but

the sort of ethical questions posed by the great realist novels have maximal narrativeness. When is there narrativeness? The more we need culture as a means of explanation, the more narrativeness. The more we invoke irreducibly individual human psychology, the more narrativeness. And the more contingent factors—events that are unpredictable from with one’s disciplinary framework—play a role, the more narrativeness.

In other words, narratives are how we process the complexities of life. If there’s an equation, no story needed. If there’s a mystery . . . well, then, tell me more.

¶ Life and fate. For what it’s worth, Patrick Collison wasn’t the only one who read Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate last year. In fact, I’d bet money he read along with the aforementioned Russ Roberts and Tyler Cowen; the pair, both economists and podcasters, invited their listeners to read along with them. Here’s their discussion.

Literature is for all of us and can speak to all of us. And as Johnson, Orlandi, Helmick, Leyland, Delistraty, and Burton all show, its magic can be both deeply practical and unnervingly mysterious.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please share it with a friend. Or an enemy. I’m not choosy.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe. It’s free and will make you a hit at all the right parties.

Insightful piece, as always! I especially resonate with the moral improvement via bypassing rational reasoning. Encountering the perseverance, steadfastness, and longsuffering of characters in many classic novels helps me to put daily trials into perspective. At the end of a long day I long to dive into these other, slower worlds and bathe my brain in long-winded conversations and a different pace of time, which in turn helps to reshape my pace.

Greetings from Boston. I just did a short video on Franklin and theological debates. And I do think it relates to something from your very fine post.

In my theological tribe of Protestant Evangelicals many read to extract a moral point or make a practical application. Nothing wrong with those things as many of them are commendable things to think and do.

The downside is that the Bible gets read in a wooden and overly simplistic way that dulls us to the complexities of living east of Eden.

Literature sensitizes us to the complexity and mystery of life. It then helps us to see that our Bibles, though having many accessible and practical things, is full of mystery and complexity as well!