The Books You Come Back To

What Are the Titles That Become Part of the Furniture of Your Mind and Alter Your Whole Attitude to Life?

I spent half a recent Saturday organizing my library. I’ve always had an unwieldy number of books, more volumes than space. It requires a fair amount of shuffling, reordering, and culling to get them shelved in a way useful to me and tolerable to my wife.

It’s pure joy.

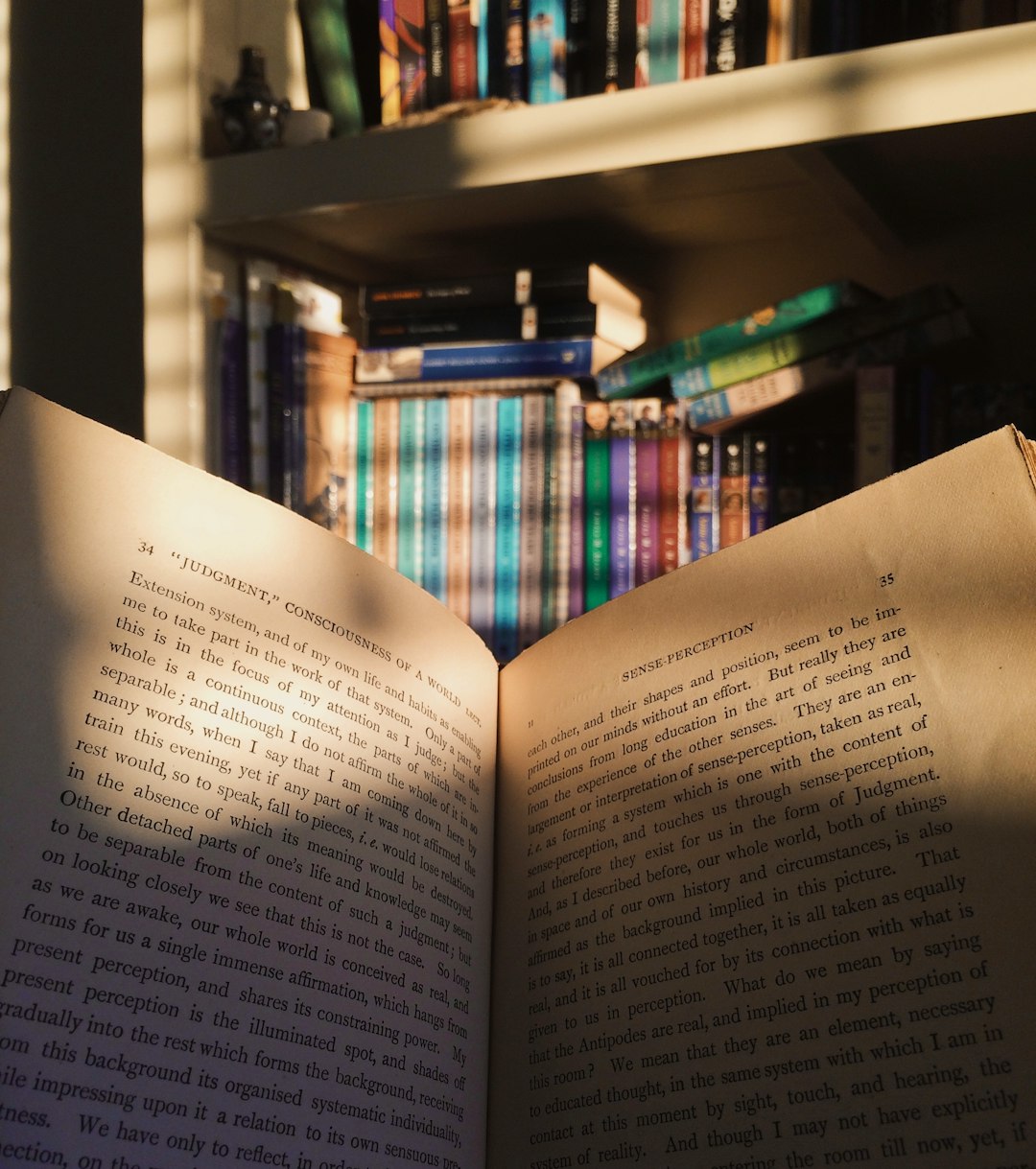

Sorting through my library is therapeutic. There are few things more enjoyable and restorative than a casual browse of books you love. A journey through the shelves allows me to get reacquainted with old friends and relations, books that might have long ago triggered a line of thinking that still holds me today.

In his 1946 essay, “Books v. Cigarettes,” George Orwell called such books those “that become part of the furniture of one’s mind and alter one’s whole attitude to life.” They are like signs indicating an altered course, intellectual and emotional bread crumbs on the trail of life. I have several titles like that. Some I may never read again, but I will never be the same again for having read them just once.

Then there are the books you come back to, the books we read over and again. These are titles we recommend but rarely lend—and sometimes regret when we do because they rarely return. They are usually improved with underlines and marginalia. And they typically migrate and meander around the house: the living room, the bedroom, the bathroom, the kitchen, wherever. There’s never a bad time or place for books like these.

I had a conversation with a friend about the books he comes back to. He regularly revisits Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. You could hear the joy in his voice as he talked about it. Another friend used to reread Thomas Howard’s Evangelical Is Not Enough. It had a profound influence on his life when he first read it many years prior. He descrbed his annual return like a guy recalling an old mentor.

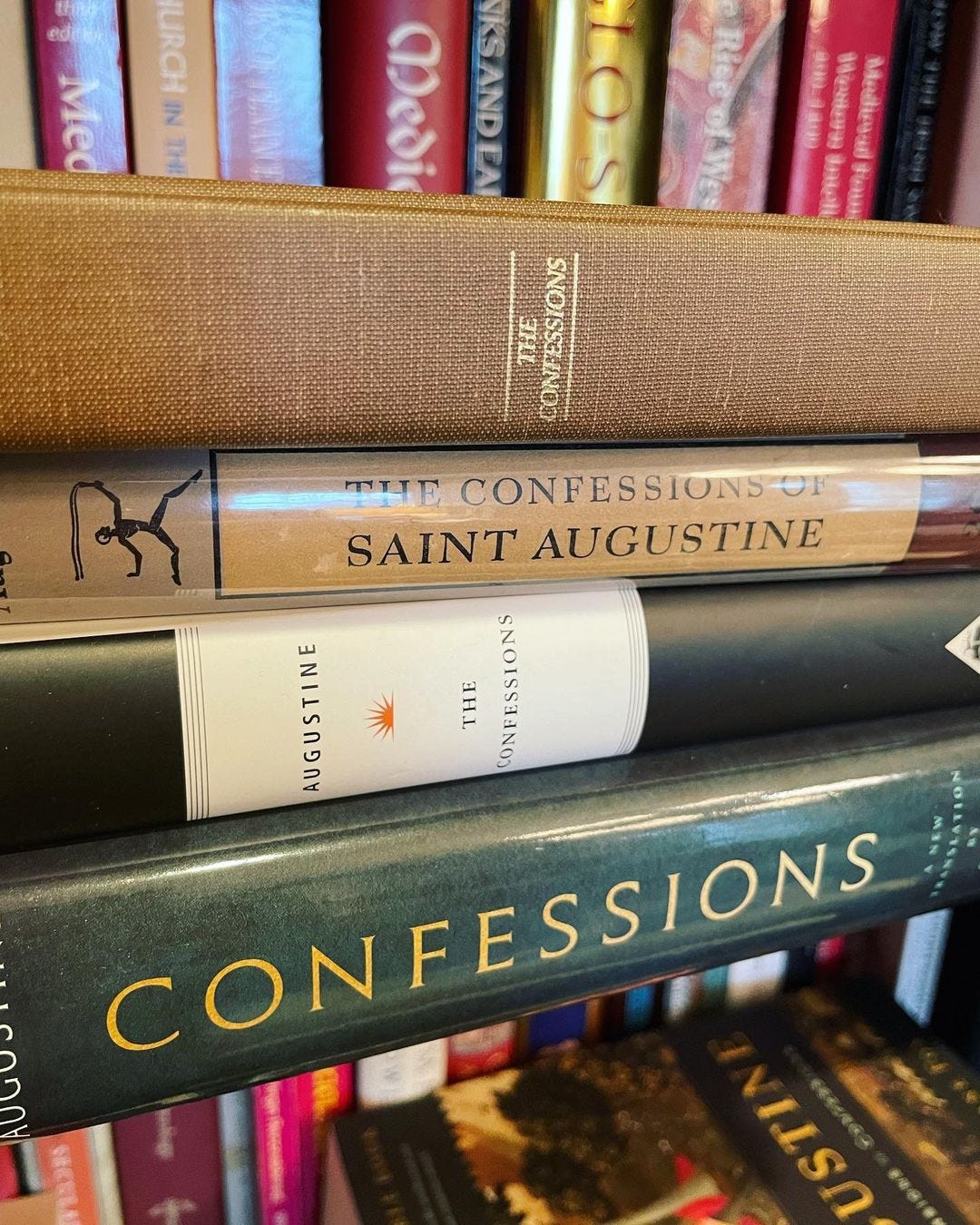

Oftentimes these books sit on our shelves a little more worn than their neighbors. Other times those neighbors are crowded by extra copies of the beloved title, different editions and treatments. At last count, I’ve got four copies of Augustine’s Confessions around here and two copies of A Mencken Chrestomathy, a much different book enjoyed for much different reasons.

What I find in conversations is that people usually have at least a few titles like this. Rereading books is one of life’s joys, and for many of us it’s a necessary part of our literary experience, even our growth as human beings. “I can’t imagine a man really enjoying a book and reading it only once,” wrote C.S. Lewis in a letter to his friend, Arthur Greeves. Greeves was apparently not much of a re-reader, but Lewis confessed it “is one of my greatest pleasures.”

One of the volumes to which I make frequent pilgrimage is Lewis’s own Till We Have Faces. It’s a stark and beautiful novel about all the good stuff—love, pride, jealousy, self-delusion. I don’t know how many times I’ve read it now, but I just can’t stop.

Montaigne’s Essays are like that for me as well. My copy follows me from room to room over the year as I pick it up and casually read a few essays here and there. I find him funny, shrewd, thoughtful, deeply feeling. I don’t know how many times I’ve read the Essays; it’s more accurate to say I’ve never stopped reading it. If someone were to ask me what I want to be when I grow up, I might say Montaigne.

And that’s partly why we read and reread in the first place. We see something of ourselves in these volumes and add their words to the sentences that describe ourselves. They are like mirrors that help us glimpse our own hearts and hopes, which might otherwise remain unknown, even hidden from ourselves.

Some books are like lamps. When a part of our experience lies half-shaded in a corner, the right book can illumine the rest. Sergei Fudel’s Light in the Darkness did that for me. Same with Our Thoughts Determine Our Lives, a collection of counsels and insights from a Serbian monk, Thaddeus of Vitovnica. If I could credit any two books for whatever spiritual maturity I possess, it would be those two.

Both men speak the faith from a cultural stance so different from my own, their every word is jarring and arresting. And yet, as I reconcile their words with my experience, I move closer their direction upon each rereading.

Other books have humbler but still important callings. Perhaps it’s a value they extol, a character we admire, an adventure we wish we could join, or a joke that just plain explains all the crazy in the world. Whatever the particular reasons for the particular book, we identify with the perspective on offer and simply can’t do without.

In that same essay, “Books v. Cigarettes,” Orwell also talked about “books that one dips into but never reads through.” I read a blurb for Barbara Brown Taylor’s book, An Altar in the World, calling it not a page-turner, but a page-lingerer.

For such books it hardly matters if you never read the whole thing. Even a few pages does you good and widens your soul. As mentioned, that’s Montaigne for me. Finishing isn’t the point; it’s all about spending time with someone special. Poetry is wonderful for such moments, as are essay collections. Humor can be the same. I’ll never tire of P.J. O’Rourke or exhaust Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary.

Some books are disposable. They leave little mark on the mind. It could be a shallow novel, something someone insisted was brilliant but wasn’t, or a book a friend recommended but you feel guilty about disliking. Don’t sweat it. Some books are more foam than beer. If and when you are faced with reducing your library, don’t hesitate giving these ones the shove.

But weigh the decision. Books that cut a new groove are almost always worth keeping. I’ve been overzealous in culling my library in the past and had to repurchase a few books over the years.

All of these words and ideas—alter, become part of you, soul-widening, and cut—say something about what books do to us. They make invitations to us and obligations on us. They force certain reckonings. And we are different after the encounter, sometimes only marginally so, other times substantially.

We always see something of ourselves in any books that matter to us. Don’t be alarmed if it’s an old version of yourself. We are continually growing and developing, and the books we read are part of that development.

That means that your library says less about your intellectual identity than it does about your intellectual development. It’s a record of your journey, the underlines and marginalia like scribblings on a vast, meandering map of the soul, every damaged spine on the shelf the record a way station on the road to you—and, hopefully, a pointer toward what might be next.

Now to you. What are some of the books you come back to? What books have left their mark on you? Share in the comments.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend. Thanks!

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. You’ll get new reviews and essays like this one each week. Thanks again!

I have several Lenten reads that I rotate through: Death Comes for the Archbishop, The Power and the Glory, and Laurus. Last year I read Graham Greene and before that it was Vodolazkin, so that means that Cather is up. I also reread Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture a lot — as well as Makoto Fujimura’s Culture Care. And I reread a bit of C. S. Lewis non-fiction like A Grief Observed, The Abolition of Man, and The Four Loves. I do like to pick up some random fiction from time to time… but more often than not I read my favorite parts of books. Like sections Lord of the Rings, East of Eden, Shakespeare’s plays (certain monologues I could just reread over and over again). Probably one of my most favorite things to read though is the first part of Luke in the Bible. The account of the birth of Christ is one I still get emotional about. I don’t know why and I suppose it makes me look like a religious nut, but it is true. Certain religious stories shock me or give me such peace.

Since I am a poet I think that it is much easier to reread my poetry collections. They are so much shorter than fiction, but there are compelling narratives in them too. Frost is wonderful for a variety of characters and ideas, and he is a joy to read aloud. Emily Dickinson was a true master, and I think everyone should have a book of all her poems.

Good post.

The book I come back to again and again is The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin, which rearranged my head, and particularly my notions of gender, and of what science fiction can be, the best part of fifty years ago.