Why Build a Personal Library?

5 Reasons Besides Being ‘Smug and Middle Class’ to Collect Books for Yourself

When Bruno Schröder died at 88, the retired German engineer left an enormous mystery. Emphasis on the world enormous. Behind the doors of his small house in the northwest German town of Mettingen, he assembled a library of 70,000 books—one of the largest personal libraries in the entire country.

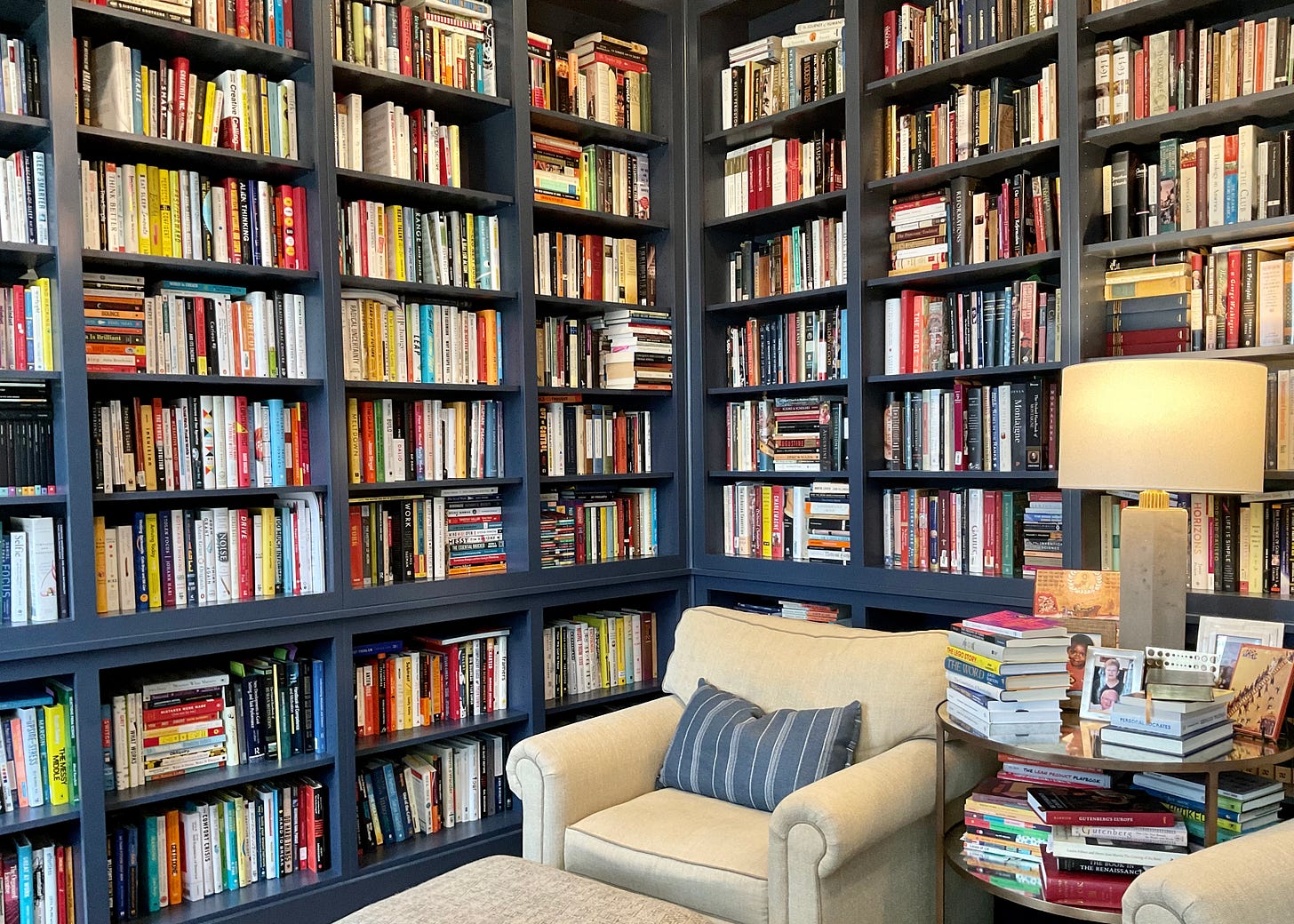

Few of his neighbors knew what he’d built. Had they crossed the threshold, however, they would have seen floor-to-ceiling shelves—some ingeniously built into the ceilings themselves—filled with pretty much everything but romance novels, which Schröder disliked.

“Schröder’s home has something labyrinthine about it,” reported Guido Kleinhubbert for Der Spiegel. From the basement to the attic, entire walls of books divide rooms filled with more books.

Schröder designed and built the shelving himself. “The most amazing pieces of furniture,” said Kleinhubbert, “can be found in the attic. . . . Schröder has equipped the sloping ceilings with shelves, which now contain around 12,000 books, all neatly sorted by publisher.” How do the books stay up while facing the ground at an angle? Shelf-wide strips of bracing prevent the tomes from tumbling. Follow the link to see for yourself.

What compelled the man to build such a massive library? No one knows, not even his wife. But, then, why does anyone collect books? You can find opinions on the question; some are better than others.

‘Smug and Middle Class’

Writing in the Guardian, Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett recently took aim at “everything that is smug and middle class about the cult of book ownership.” She clarified, “I don’t mean reading. . . . No, I specifically mean having a lot of books and boasting about it, treating having a lot of books as a stand-in for your personality, or believing that simply owning a lot of books makes one ‘know things.’”

But, seriously: Who does that? I know plenty of people who own plenty of books. Most are, admittedly, middle class. (Is that supposed to be a bad thing?) Only one is smug. And none possesses books to brag about them, or as a replacement for their personality, or on the mistaken belief they might magically accrue knowledge by osmosis.

I’m sure there are people who do own books to make themselves look smart. You can buy books by the foot if you need. But just think of all the book owners you know. If there are any who fit that bill, I bet they’re few in number.

No, I’d wager most of the book owners you know are like those I know, and probably like you or me: They own books for practical reasons any serious reader would recognize. I count at least five off the top of my head.

1. To See How You Got to Now

Seeing a book is like hearing a song. Music can transport us through time to significant moments and periods of personal pain and joy, struggle and growth. When I hear Tom Petty’s “Runnin’ Down a Dream” I’m suddenly behind the wheel of my first car, a 1977 AMC Hornet, tooling around Northern California. It’s the same with glancing down my shelves.

A personal library is, among other things, a map of where we’ve been, a track through time that helps us understand the way we’ve come. This is all the more so because books are very often the catalysts for the very turns and transitions to which they testify. “There are,” as legendary Johns Hopkins professor Richard Macksey once said, “little bits of yourself that are scattered around the library.”

When I see, for instance, Virginia Postrel’s The Future and Its Enemies, I recognize a formative voice in my intellectual development, one that helps explain my current attitudes about innovation, free inquiry, and economic growth. When I see Giles Milton’s Nathaniel’s Nutmeg or Barry Cunliffe’s The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek, I see moments that opened my imagination about trade and world history, which remain passions to this day.

Books trigger transformation in our lives, and keeping a copy allows us to access those moments for all sorts of reasons: self-exploration, renewed excitement, gratitude, ongoing curiosity, and more. You’ll never reread that old book for the first time, but revisiting a copy on your shelf can help you recapture a memory—just like finding an old photo or replaying a favorite song.

Several years ago the Christian public intellectual, Russell Moore, gave his readers a tour of his substantial home library that demonstrates this point. As he walks us past one shelf and then another, he can’t help but explain how particular books and authors played into his intellectual and spiritual development.

Anyone with a home library probably has some version of this. “Sometimes I stop in the center of my own home like a bird arrested in flight, entranced by the books that line my walls,” says actress and writer Leslie Kendall Dye. While her New York apartment is small, Dye has crammed the living room, hallway, closets, and bedroom with books.

“I marvel that the complexity of the human heart can be expressed in the arrangement of one’s books,” she says, speaking of the psychological power of her collection:

Inside this paper universe, I find sense within confusion, calm within a storm, the soothing murmur of hundreds of books communing with their neighbors. Opening them reveals treasured passages gently underlined in pencil; running my hand over the Mylar-wrapped hardcovers reminds me of how precious they are. Not just the books themselves, but the ideas within, the recollections they evoke.

If you’re looking to better understand yourself, look back at the books you’ve read. Assembling a personal library of whatever size is an act of self-revelation. “No matter what a person studies,” says novelist Eugene Vodolazkin in Solovyov and Larionov, “above all he is studying himself. . . . Accidental topics do not exist.”

(I, by they way, cover this idea in additional detail in “5 Reasons to Write In Your Books.”)

2. To Do Your Job

In a real and practical sense, as philosopher Andy Clark argues, a bookcase is an extension of our cognitive workspace; our books are part of our mind. If you’re in any sort of knowledge work, books are among the essential tools of your trade.

A couple doors down, my neighbor has shelves of books by English Puritans. Why? He’s a pastor with thing for Reformed theology. That’s what’s going on with Moore’s collection, as well: It’s part of how he does his job.

To the right of my desk, I have a wall of books, about half of which are related to my business interests and which I consult on a regular basis while developing content at work. I’ve got everything from neuroscience to motivational research, economics, productivity, innovation, and some relevant biography and history all within easy reach.

Books allow knowledge workers access to the ideas that make their work possible. First, as reference for one-to-one uses like citations. Second—and vastly more important—for one-to-endless uses in triggering new thoughts. A working library allows us to build a baseline of knowledge in one or more fields. But it also facilitates recombining and extending that knowledge in novel ways. A good library is an idea machine.

Richard Macksey, quoted above, moved into his Baltimore, Maryland, house in 1962. For the next fifty-seven years, he added to his personal library, finally hitting 51,000 volumes by the time of his death. You’ve probably seen an image of it on social media.

Macksey passed away in 2019. And while his library certainly fits Reason No. 1 above, it was a working library above all. He conducted seminars in his home, and he and his students used the collection in their work. Many of those students mentioned his prodigious learning and library upon his passing. Here’s Hollis Robbins, now dean of humanities at the University of Utah:

Johns Hopkins prepared a video showcasing Macksey in action, surrounded by his books. It’s worth watching for the inspiration alone.

If you trade in ideas, you rely on books to one degree or another. Building a library is part of how you do your job, and building a great library is how you excel at your job. I suppose saying so risks causing Cosslett some involuntary wincing; stressing the virtues of a working library sounds thoroughly middle class. Of course, there are still other reasons besides.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about reading and books.

3. For Personal and Professional Development

Do you ever marvel that you can pick up an idea first expressed in writing 2,500 years ago, try it on for size, and apply it to your life today? Books are disembodied teachers that speak across centuries and cover geographical distances we could never traverse in person.

If books map our prior evolution, they also provide trajectories for future growth. Bookcases serve as both catalogs of inspiration and programs of aspiration.

“If the books on my first bookshelf were once signals for who I wanted to be,” said Bryan VanDyke about moving into a new apartment with enough books to disgruntle the movers, “then the books on those Brooklyn shelves were reminders of what I still needed to do. . . . The rows of books were long lines of dares, double dares, triple dares. Get to it, boy, their spines all read.”

Books represent agendas for living, creating, designing, and building. By assembling a personal library we’re creating an intellectual board of advisors, a committee of consultants that might include everyone from Aristotle to St. Augustine, Montaigne, and—who knows? You choose. It’s your library!

Gaining the insights you need from personal relationships alone is limited to your context and your network. But you have nearly unlimited access to authors—at least to their published thoughts. And maybe that’s best. After all, as Raymond Chandler said, “If you liked a book, don’t meet the author.”

Both personal and professional development emerge from the stacks of Macksey’s library. With a mentor like him, surrounded by the wisdom and folly of the ages, who wouldn’t imagine diving in for a lifetime? A good book calls us to itself and hints where to next.

4. Everyone Needs a Hobby

Schröder filled his final days with work on his collection. “The old man probably tried to complete and archive his collection until the end,” said Kleinhubbert, who reported seeing notes and paperwork on his desk.

Medical professionals had urged him to enter a retirement home, but Schröder chose to stay with his collection. “Schröder lived for his books,” said Kleinhubbert, “he refused to leave them.” This is not a simple case of hoarding. Schröder was meticulous about records and organization and methodical about acquiring and displaying his books.

However extreme, this points to another, simpler answer. It was his hobby, a project the consumed his mind and available time. Who’s to judge? “Prod any happy person,” says economist Richard Layard, “and you will find a project.” Book collecting was a harmless activity that seems to have brought Schröder joy.

This rationale forms a natural rejoinder to Cosslett’s tsk-tsky ethic of library liquidation. Books bring joy for reasons we’ve already covered and others besides. There’s something rewarding about collecting particular titles and authors with personal significance.

My friend Gabe has a marvelous collection of rare first editions of Southern authors, such as novelist Walker Percy, poet Allen Tate, and the Fugitives, all wrapped in Mylar like Dye’s hardbacks. These books represent part of his intellectual and psychological formation. He honors and their role in his life by finding choice examples of their work.

My collection is more workaday by far, despite some early interest in collectible editions of Percy, Cormac McCarthy, and a few others. I still seek to fill out holes in my C. S. Lewis shelf—I think I’ve got most everything at this point—and, especially, my shelves of book history. Those needs are purely in the domain of the hobbyist. And they’re every bit as valid a reason to assemble a personal library as the other reasons already offered.

I think you can see Reason No. 4 poking out from behind an apparent appeal to Reasons No. 1–3 in this bit from professor David Henkin on books as time machines:

Students entering my office sometimes inquire whether I’ve read all the thousands of books that line its walls. . . . I might expect them to ask whether I aspired to read all these books. But whether books represent our past experiences or our dreams for the future, the way we showcase and arrange them seems interesting in an age in which databases and search engines have eclipsed books as tools for looking things up. Displayed books gesture forward and backward to acts of reading and rereading; of purchasing, posing, moving, and unpacking; of passing time and dropping into its folds.

Displaying books here transcends the professional reasons. It’s a meaningful activity unto itself, what philosopher Kieran Setiya would call an atelic activity. And the joy obviously doubles when taking down books from the arrangement—“passing time and dropping into its folds.”

Maybe Schröder thought he was buying himself time, “dropping into its folds,” as he built his exhaustive inventory and browsed his neatly ordered spines. I bet there’s little more to the mystery than that.

None of us has to go to his extreme to find the same sort of temporary relief, even joy, in the face of time’s relentless pace. Assembling a small collection of books and authors you love is all you need. Nothing culty or smug about it.

Cosslett recommends reading what you want and then giving the books away. I certainly don’t recommend keeping them all. But passing along most every book you read renders it nearly impossible to gain the benefits we’ve covered so far. And the same is true for my final reason, as well.

5. To Find Solace in the World

When Machiavelli found himself exiled from Florence, his productive life was practically over—so he assumed. He spent his days managing a rundown farm and playing cards with local peasants. But at night, things changed. As he wrote in a famous letter to a friend,

When evening comes I return home and go into my study. At the door I take off my everyday clothes, covered with mud and dirt, and don garments of court and palace. Now garbed fittingly I step into the ancient courts of men of antiquity, where, received kindly, I partake of food that is for me alone and for which I was born, where I am not ashamed to converse with them and ask them the reasons for their actions. And they in their full humanity answer me. For four hours I feel no tedium and forget every anguish, not afraid of poverty, not terrified by death. I lose myself in them entirely.

Those ancient courts were the pages of books. This sounds very much like Reason No. 3. But notice it’s more. He doesn’t just ask his committee of classical authors their advice so he can immediately go do what they suggest. He has no power to do anything. Instead, their words salve his wounded pride and his doctor the injury done his career prospects.

He turns the pages and his trials vanish: “I feel no tedium and forget every anguish, not afraid of poverty, not terrified by death. I lose myself in them entirely.”

Montaigne, who built himself a tremendous working library to which he repaired in his retirement, said something similar a generation later. “To be diverted from a troublesome idea,” he said in his Essays,

I need only have recourse to books: they easily turn my thoughts to themselves and steal away the others. . . . I cannot tell you what ease and repose I find when I reflect that they [books] are at my side to give me pleasure at my own time, and when I recognize how much assistance they bring to my life. It is the best provision I have found for this human journey. . . .

When I went through my divorce in 2006 all I did was read fiction. Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses was a balm to me. Mario Vargas Llosa took my mind to different places with people whose lives were worse off than mine. And T. C. Boyle did whatever it is that T. C. Boyle does; The Tortilla Curtain still strikes me as a perfect novel.

Of course, Machiavelli and Montaigne’s libraries were nowhere near as large as the average acquisitive person can manage today. Books are remarkably cheap and abundant. That leads to a natural question:

How Much Is Too Much?

It’s hard to fathom 70,000 books. Same with 51,000. Even smaller libraries defy comprehension and complicate management. But those are individual determinations—or should be. Here’s a rule of thumb: If the size of your library is too large to receive the benefit of the five reasons above, it’s probably time for some culling. Outside of that, I don’t see the problem of a library growing as large as you like.

As alluded to above, I used to dabble more seriously with collecting for the sake of collection. It was a phase. I love books, and I can appreciate a rare first edition of something. But my personal library these days is mostly a working library, even the hobby side. If I can’t find or use the books in it, I’m happy to let some go to keep it a manageable size. I regularly donate books to my local library to clear them out when I need.

I’ve got about 1,500 books right now, most of that in my study. At the moment, that’s about all I need or want. Ask anyone who knows me: I’m a minimalist. My entire wardrobe fits in one corner of our walk-in closet. I don’t like owning much. Possessions require upkeep, libraries included. Washington Post critic Michael Dirda offers a case study in what happens when a collection grows too large to manage. No thanks.

There’s one more consideration, of course, mentioned in Bryan VanDyke’s story above: moving. Literary agent Lynn Johnston recently tweeted:

Humorist Fran Lebowitz keeps about 12,000 books. “I am unable to throw a book away,” she told Washington Post reporter Karen Heller. “To me, it’s like seeing a baby thrown in a trash can.” Moving apartments is a chore, but Heller says Lebowitz hires specialty book movers to convey her collection from Point A to Point B.

Sometimes that moving is permanent. Libraries only last as long as people find them useful. Personal libraries, then, possess one sobering vulnerability. Someday their owner will die, and then what? You can find pictures online of Macksey’s empty house, all the books gone. Most carefully assembled collections end up dispersed to who knows where.

Rehoming Schröder’s books won’t be easy. Virtually no one is prepared to take on a collection like that, as Kleinhubbert reported, even to process it for sale. Johns Hopkins was able to absorb about 35,000 volumes of Macksey’s library. But finding an institutional partner with ample capacity isn’t easy; in Macksey’s case it’s only his long-standing connection to the university that made the accession possible. Lebowitz hopes three bibliophilic friends will take her collection when she dies.

All of the above reasons, and certainly this final consideration, are personal and must be weighed accordingly. Cosslett has run the cost-benefit analysis for herself and has decided to get rid of most of her books. Personally, I think that’s a terrible decision. But who cares? It’s a big world, and she’s free to do what she likes.

So are you, naturally. And there are many reasons beyond these five to build a personal library of your own, even if you’re smug and middle class.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please share it with a friend.

More reviews and bookish diversions are on the way. Don’t miss out!

Since I started reading your Substack two months ago, this is the best post you’ve published (all the others were good too, of course). I started building a personal library in college over 17 years ago and I haven’t looked back. Now, I’ve got roughly 3,500 books, and I love them all. The biggest ongoing fight between me and my wife has been the amount of money I’ve spent -- and continue to spend -- on books. That, and the adjacent problem of not having enough space to keep them all.

What’s ironic about my obsessive love for books and reading is that, as a child and adolescent, I struggled to learn to read. My parents sent me to several special tutors as a child, but nothing seemed to help. Then, one day my freshmen year of college, I had this deep pull to pick up a book and start reading. From that moment 17 years ago until today, I’ve mostly lived with my face planted between the covers of a book. Books have changed my life. They’ve opened doors of opportunity I never imagined were possible for me as a struggling student. Looking back, I firmly believe reading was an unexpected gift given to me by God. I have no clue why He did it, but I’m grateful every day that He did. I can’t image my life without books.

Thanks for writing this; reading it has made my day.

What a joy it was to read this post! I am a lover of tangible books - one my favourite places was a recycling depot that had a wall of shelves filled with books that were destined for garbage, but were given a short reprieve in case anyone wanted them. As a homeschooler this was a treasure trove for our family; my children would joyfully return to those shelves every week and would come across incredible finds (one was an original1867 civil war poetry book, and my favourite was a 1st edition Count of Monte Cristo).

We continued to add to our library over the last decade from various book and garage sales and have 17 book shelves in our home. Each comes with a different flavour: classics, children's books, history, reference, modern classics, Tolkien and Dickens get their entire own shelves....

We also built a small library box outside our house, where people can take and bring books:)

One of the reasons for building a personal library I would add to your list is that tangible books do not change; they don't get altered, censored, or deleted. I noted that the selection in public libraries is getting more and more narrow, focusing in modern or trendy topics, leaving classics in the dust because they might contain a theme or phase that is fallen out of favour. Thus having our personal library preserves access to tradition and history that is fading away from public view.

Thanks again for your post!