No Easy Money, But What If?

Everybody’s Got an Angle: Reviewing Chester Himes’s Noir Classic ‘A Rage in Harlem’

What if someone told you they’d perfected a process that would turn ten dollar bills into hundred dollar bills? Would you fork over your stash in hopes of becoming instantly wealthy? Unfortunately, I’m afraid the lovelorn, naive Jackson isn’t as smart as you.

I had no idea what to expect with Chester Himes’s 1957 noir classic A Rage in Harlem. “Reading the Harlem crime novels of Chester Himes is such a vivid experience,” says one critic, “that certain passages have found their way into my dreams, and it’s a 50-50 chance whether I wake up laughing or screaming.” Meanwhile, novelist S.A. Cosby labels him “the songwriter of the downtrodden.”

I can’t say I found anything in Rage that matches Cosby’s description, nor anything that left me screaming in the night. I did, however, laugh like a fool and flip the pages as fast as I could to keep pace with what that first critic referred to as Himes’s “escalating calamities” and “almost demented slapstick violence.”

Action Jackson

Jackson, as it happens, is a bigger fool than me. Himes drops us into the middle of the money “raising” scam. Jackson’s girlfriend Imabelle can’t quite escape her violent con-artist husband, Slim. He’s convinced her to lure Jackson into the scheme whereby bills are supposedly altered chemically to boost their denomination. “If you are not drunk, you is crazy,” one woman tells Jackson when listening to him explain the plan.

Insane, but the crooks give Jackson a demonstration and he falls for it. Jackson’s in for every penny of the $1,500 he’s painstakingly saved up.

When the scam blows up—literally—Slim’s crew skedaddles with Jackson’s money, Imabelle too, and Slim, while posing as a US marshal, shakes down Jackson. But Jackson doesn’t have a dime to his name any longer. So Slim drives Jackson to his employer’s, H. Exodus Clay’s funeral parlor, where Jackson steals $500 from the company safe. Jackson pays off the phony marshal with $200 and pockets the remainder. Still believing in the scam, he hopes to find the runaway scam artists, “raise” the $300 to $3,000, and pay back Mr. Clay before his employer notices the money’s missing. What could go wrong?

The story is already surreal, impossibly zany, and it we’re only getting started.

When the nearly pious Jackson can’t find Imabelle or the guy who knows the secret to raising his money, he visits his pastor and hopes prayer will help. Rev. Gaines questions Jackson about his plight and begins to pray. But when the reverend’s housekeeper says lunch is served, he abruptly ends his heavenly petition, says, “The Lord helps those who help themselves,” and runs off to eat.

So Jackson does the next best thing and hits the dice tables, hoping to win enough money to cover what he owes his boss. If only. He loses the rest of the money and is reduced to calling on his twin brother, Goldy, a petty criminal who cross-dresses as a nun and scams donations from the gullible with misquoted scripture and tickets to heaven.

What is even happening here?

An Unlikely Rise

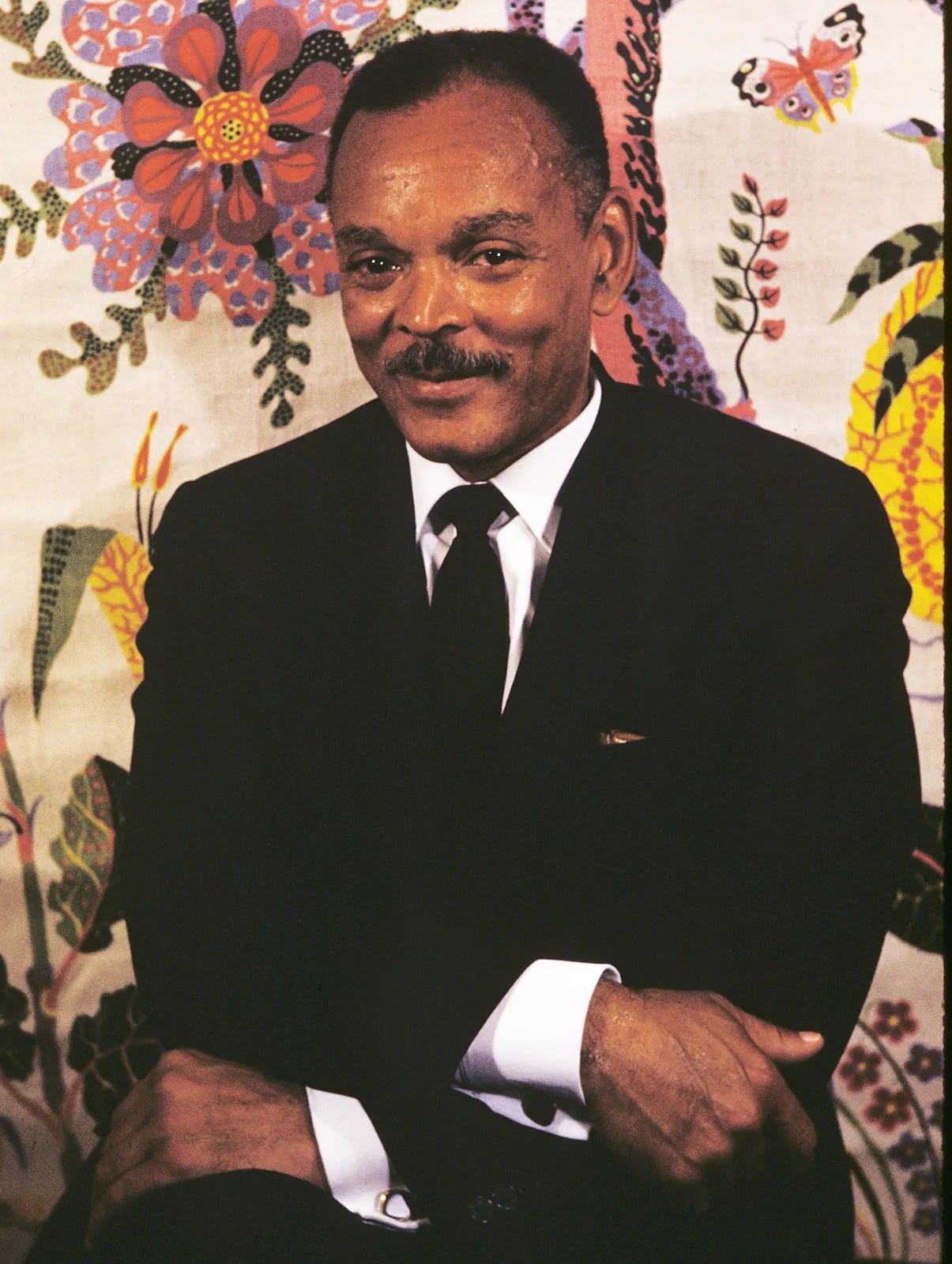

Born into a middle-class black family in 1909 amid domestic strife, Chester Himes struggled to find his way forward. So he went backward, eventually landing in prison for armed robbery at age nineteen.

While in the clink, Himes began writing, first submitting stories to smaller journals and then eventually Esquire magazine. What else was he going to do? “I began writing in prison,” he recalled. “That . . . protected me against the convicts and the screws.” Besides, the exercise helped him process some of the horrific experiences he endured, including a fire in 1930 that killed more than three hundred inmates.

Released in 1936, he eventually met Langston Hughes who introduced him to literary life and circles. But he couldn’t focus solely on his writing; he had to work to survive and struggled with that. “Over a period of three years, he held a total of twenty-three jobs,” writes Hilton Als, “most of which involved manual labor.”

Himes was unhappily married by then, a situation no doubt complicated by his womanizing and alcoholism. Still, he made time to write and by 1945 had published his first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go. The book was critically acclaimed and paved the way for a few additional novels, none of which performed as well as the first. These early stories, steeped in realism, race rage, and despair, later helped win him the “the songwriter of the downtrodden” label, but they didn’t sell much at the time.

In 1953, he left his wife and moved to Paris, where he chummed around with James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and other expat writers. It was also where he got lucky. In 1956, French editor Marcel Duhamel approached him about writing crime fiction. “Duhamel published American crime novels for a French audience . . . obsessed with the form,” explains Nathaniel Rich, “and he offered Himes a large advance to write one.” Bingo.

A year later France went nuts for A Rage in Harlem, inaugurating a string of commercially successful Harlem-based detective stories that transformed Himes’s professional prospects and introduced his two most enduring characters, the black police officers Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. Despite their later prominence, this unlikely duo of skull-crushers play second fiddle in their Rage debut to Jackson and his cross-dressing brother, Goldy.

Gold for the Taking

Sitting here with my copy in hand, I find summarizing it challenging. “Escalating calamities” and “almost demented slapstick violence” remain apropos. But cataloguing the narrative twists and turns, when every cockamamie detail seems to help explain the criminal circus conjured by Himes, is impossible, laughable. You’re better served if I simply hand you a copy.

The entire story is ludicrous, and yet you give yourself over to every page because it’s masterfully written, amusingly plotted, deviously zany, and laugh-out-loud hilarious—including how he plays with his character’s religion. “If Christ knew what kind of Christians He got here in Harlem,” says Jackson’s landlady, “He’d climb back up on the cross and start over.” When Jackson flees one of his many crises in a taxi, he tells the young driver he’s in a hurry. After the driver flips a reckless U-turn and pounds the gas, Jackson clarifies, “I ain’t in no hurry to get to heaven.”

“We ain’t going to heaven,” says the driver.

“That’s what I’m scared of,” says Jackson.

As Jackson reads Goldy in on his problems—the money, the girlfriend, all of it—the brother spots a possible angle for himself. Imabelle is sitting on a trunk full of gold, Slim’s gold, supposedly mined from hole in Mexico. The scheme they’re planning to run includes giving high-dollar Harlem residents preferential, insider treatment on buying shares in the mine. What a deal!

Goldy wants to get his hands on it. The trouble? It’s not real. The successive predicaments in which Jackson and Goldy find themselves trying to chase it down, however, are almost lethally real. At one point Jackson finds himself in the middle of a shootout between Slim’s hoods and Grave Digger and Coffin Ed. He escapes with his life, evading police pursuit, and finally makes a painfully slow getaway by stealing a junkman’s wagon pulled by a “mangy, purblind, splay-legged horse that would ever eat grass again.” For Goldy, you can drop the “almost.” The street-smart nun pushes his luck one too many times.

Just when the situation can’t get worse, it does. Jackson has returned to his employer, not to pay back the money, but to steal a hearse so he and Goldy can haul off the gold trunk. They get the trunk, but Goldy gets knifed by the hoods and stuffed in the back of the car while the weary Jackson nods off for a catnap. A moment later Jackson finds himself back behind the wheel with a trunk of stolen gold and the body of his dead brother—in a hearse!—now racing from the law.

Turn of Luck

Thankfully, Jackson is a better driver than he is a judge of character, at least insofar as maneuvering the hearse down busy roads to evade arrest. He flies down the streets, dragging the eyeballs of onlookers as he goes. When the Saturday-morning Harlem Market comes into view—vendors unloading their wares and setting up their booths—Jackson points his car toward whatever opening he can find and pushes through, “like trying to thread a needle with a heavy piece of string.”

It’s a clumsy but effective effort:

The right wheels of the hearse had gone up over the curb and plowed through crates of vegetables, showering the fleeing men and the store fronts with smashed cabbages, flakes of spinach, squashed potatoes and bananas. Onions peppered the air like cannon shot.

“Runaway hearse! Runaway hearse!” voices screamed.

The hearse ran into crates of iced fish spread out on the sidewalk, skidded with a heavy lurch, and veered against the side of the refrigerator truck. The back doors were flung wide and the throat-cut corpse came one-third out. The gory head hung down from the cut throat to stare at the scene of devastation from is unblinking white-walled eyes.

Exclamations in seven languages were heard.

Along the way? The back doors of the hearse fling open again and the trunk slides out of the back onto the street. Jackson realizes the trunk is gone when he comes to stop in front of his preacher’s house. He runs inside and confesses the whole twisted story to the reverend. The preacher sits there listening to the recital with his mouth open and eyes widening.

“The Lord won’t get you out of that kind of mess,” he finally says.

Thankfully, Mr. Clay does. I won’t say how—or what was really in that trunk—but suffice it to say Jackson proves a lucky man in the end. He even gets his girl back, though how long Imabelle will hang around is another question.

France went nuts for the story, but so did readers in the U.S. “The applause from France grew so loud that American critics were compelled to join in,” says Michael P. Jeffries, “and Himes eventually earned the status he had craved for so long back in the United States.” That status has dimmed since his death in 1984, but Himes’s publishers and fans have kept his work alive for anyone willing to keep pace with those escalating calamities.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

And while you’re here, check out:

"...the black police officers Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson..." Those are cold-blooded handles! (On film, they would be portrayed, respectively, by Godfrey Cambridge and Raymond St. Jacques in "Cotton Comes To Harlem" and "Come Back Charleston Blue", both directed by Ossie Davis.)

Sounds like a great read! Thanks.