A Monster’s Wish: The Friendship Missing from ‘Frankenstein’

Reviewing Mary Shelley’s Classic Novel

Stoicism has benefited from a recent wave of renewed popularity. Want to learn how to order your life? Read the Stoics—or at least their updaters. But economist Adam Smith would like to object. His recommendation? Read novelists instead.

Smith pits writers such as Samuel Richardson, author of the epistolary novels Pamela and Clarissa, against the founders of Stoic thought. “The poets and romance writers,” he says in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, “who best paint the refinements and delicacies of love and friendship, and of all other private and domestic affections . . . are, in such cases, much better instructors than Zeno, Chrysippus, or Epictetus.”

It’s a safe bet that Smith would have adored Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, originally published in 1818, not quite three decades after his death, especially for its profound thinking on friendship. We’d all benefit from letting Shelley’s masterpiece pass beneath our eyes at least once—and probably many times more—not only for its surprising narrative force but for its moral power.

Shelley grounds the entire story in themes of friendship and companionship—what humans need from, and owe to, each other.

For Want of a Friend

The novel takes its shape from a series of confessions. First, the letters of Robert Walton, then the revelations of Frankenstein, and then those of Frankenstein’s Creature. From there it moves back to Frankenstein and then again Walton, like so:

Robert Walton

↳

Frankenstein

↳

Creature

↲

Frankenstein

↲

Robert WaltonThe story begins with Walton on an Arctic journey, traveling to where humans have never been. “I shall satiate my ardent curiosity with the sight of a part of the world never before visited, and may tread a land never before imprinted by the foot of man,” says Walton in a letter to his sister Margaret. “These are my enticements, and they are sufficient to conquer all fear of danger or death. . . .”

So we have our stalwart adventurer. But then, curiously, in his next letter Walton laments his loneliness. “I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy,” he says, “and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil. I have no friend, Margaret. . . . I desire the company of a man who could sympathize with me; whose eyes would reply to mine. You may deem me romantic, my dear sister, but I bitterly feel the want of a friend.”

He finds one soon enough—or at least he finds a man he hopes might become his friend. After Walton’s northbound ship gets trapped in the ice, the men aboard catch sight of a gigantic man driving a sledge pulled by dogs, vanishing in the distance.

Soon after they rescue another man near death on an ice floe, the bedraggled Victor Frankenstein. “I have found a man who, before his spirit had been broken by misery, I should have been happy to have possessed as the brother of my heart,” writes Walton to his sister.

Frankenstein has been broken by misery, and he proceeds to tell Walton his woes. It all begins well enough. Raised in a loving home, he finds solace in friends, particularly the young Elizabeth Lavenza, his adopted sister and near-fated fiancée, and Henry Clerval, a companion that would have Walton jealous—a counterpart who tries at all adventures to salve his friend’s troubled spirit.

And what troubles the young Frankenstein? His studies to begin with.

Selfish Pursuit

Rejecting the mild but dismissive cautions of his father, Frankenstein dives headlong into crackpot alchemical theories masquerading as science. These are challenged when he attends university but, despite a brief detour, that rejection only drives him deeper into himself in an effort to reconcile the ancient mysteries with the burgeoning natural sciences. The pursuit drives him mad—or at least obsessed beyond all reason.

“Two years passed in this manner,” he says, “during which I paid no visit to Geneva [home], but was engaged, heart and soul, in the pursuit of some discoveries which I hoped to make.” Frankenstein shuts out the world, including family and friends, to serve his obsession.

Instead, he says, he spent his time among the dead. “Darkness had no effect upon my fancy,” he says,

and a churchyard was to me merely the receptacle of bodies deprived of life, which, from being the seat of beauty and strength, had become food for the worm. Now I was led to examine the cause and progress of this decay and forced to spend days and nights in vaults and charnel-houses. My attention was fixed upon every object the most insupportable to the delicacy of the human feelings. I saw how the fine form of man was degraded and wasted; I beheld the corruption of death succeed to the blooming cheek of life; I saw how the worm inherited the wonders of the eye and brain.

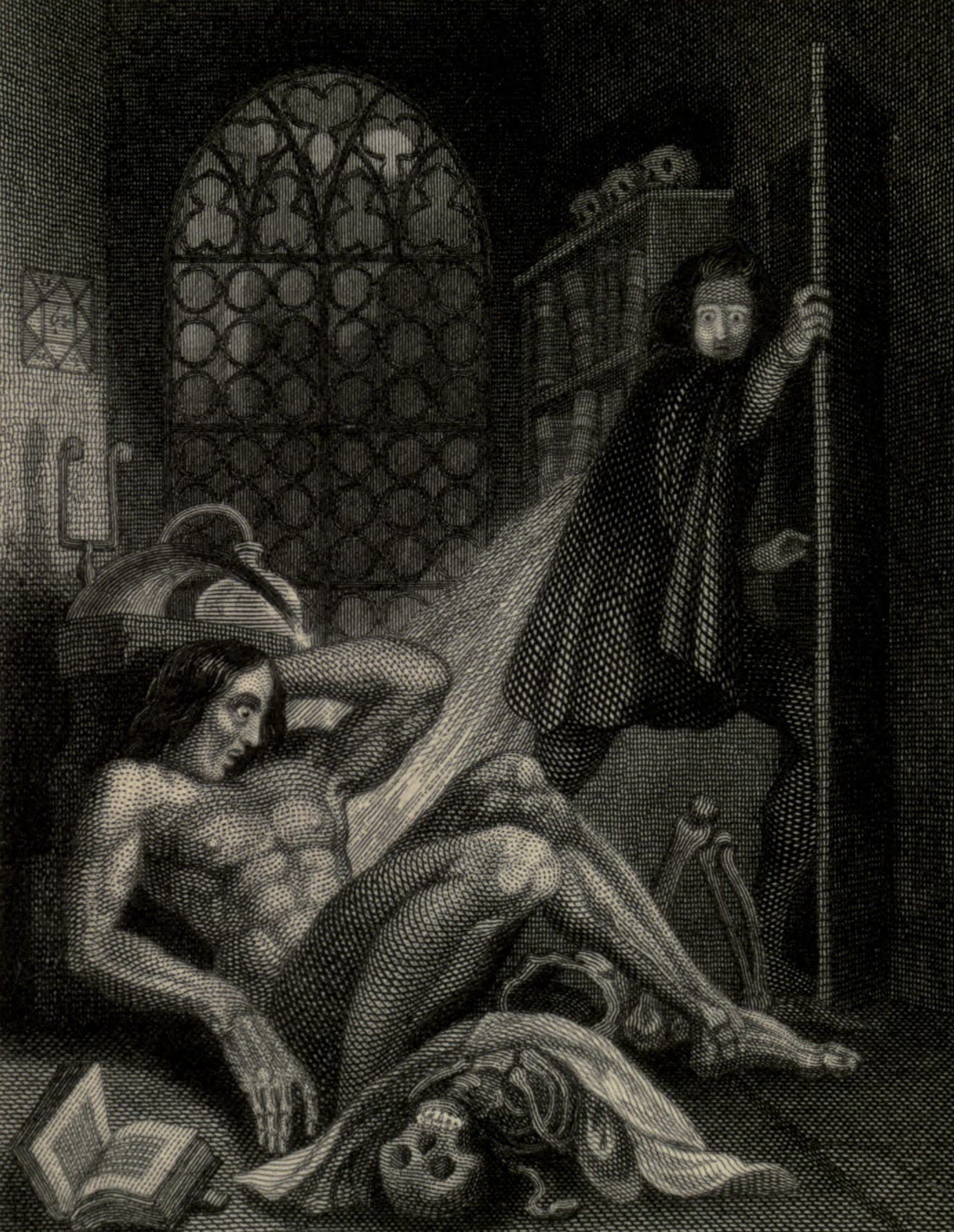

It’s during these morbid hours of self-isolation that Frankenstein believes he now finally understands how to conjure life from death. He gathers the necessary materials—body parts, though Shelley is purposefully vague—and beavers away until one day “I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open.” The triumph is ghastly. Frankenstein, horrified by his awakening creation, flees the room.

Later that night, after the creature looms over his sleeping creator in bed, Frankenstein jolts awake and runs out of the house. When he later encounters his friend Clerval, who he hasn’t seen in now two years, Frankenstein returns home to discover the creature has fled and is no longer there. He’s relieved. He’s elated! What’s more, Clerval carries a letter from his dear Elizabeth.

With the horrid creature gone God-knows-where and Clerval and Elizabeth back in his life, Frankenstein feels as though this terrible chapter of his life—“this selfish pursuit” that had “rendered me unsocial”—is finally closed.

Months pass in relative bliss and Frankenstein plans to return home. But that’s when he receives a dreadful missive from his father. William, Frankenstein’s little brother, has been murdered. A woman in the home who cares for the child has been accused, but Frankenstein suspects something different; he knows his horrid creature has robbed the tender boy of his life.

Meanwhile, the creature has a perspective of his own.

Rejected and Alone

Having retreated on an Alpine vacation, Frankenstein decides to summit a certain peak alone, but there amid the sharp ice and treacherous terrain the creature confronts him. And his complaint? Abject loneliness.

“Remember, that I am thy creature,” he implores.

I ought to be thy Adam; but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Every where I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. . . . Believe me, Frankenstein: I was benevolent; my soul glowed with love and humanity: but am I not alone, miserably alone?

At every level of the narrative, Shelley works in her theme: first, friendless Walton writing home from the icy North, then Frankenstein vacillating between companionship and isolation as he pursues his obsession, and now the creature himself. The crux of his complaint? He’s friendless, and it’s Frankenstein’s fault for abandoning him.

After the creature fled, as he tells Frankenstein, he eventually found shelter with a family in the countryside. Though he remained hidden from view, it was largely from observing them he learns the ways of the world—language, kindness, and the viciousness of humankind.

“I longed to join them,” he says. He finds human society baffling but feels shame from his exclusion. As his loneliness grows acute, he finally hazards contact. Alas, he’s rebuffed. The family finds his appearance shocking and, assuming him to be a threat, drive him away. Is there no one he can call friend?

Rejected by humankind, he rejects humankind. “From that moment I declared everlasting war against the species, and,” he says, “more than all, against him who had formed me, and sent me forth to this insupportable misery. . . . I bent my mind towards misery and death. . . . Inflamed by pain, I vowed eternal hatred and vengeance to all mankind.”

Shortly thereafter, he claims his first victim by force, then a second by mischief. But he’s not entirely ready to destroy his creator—not yet. First, he demands Frankenstein go back to the lab and create him a partner by the same means he coaxed the creature’s life from inanimate flesh and bone.

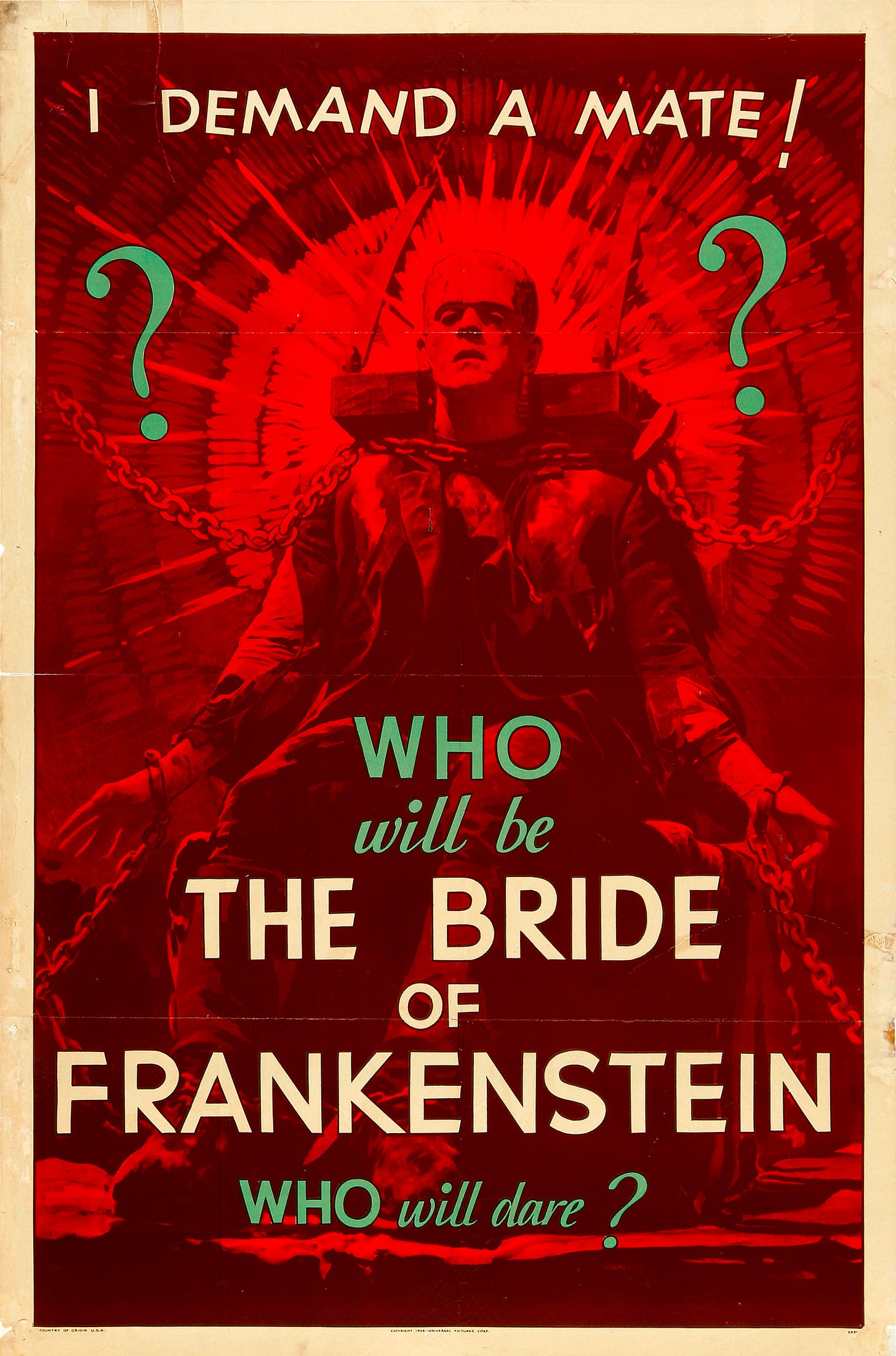

“You must create a female for me,” the creature says, “with whom I can live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being. This you alone can do; and I demand it of you as a right which you must not refuse.”

Promise and Betrayal

The creature’s appeal, says Frankenstein, “had a strange effect on me.” He agrees to do it, agrees to fashion an Eve for his monstrous Adam. “I consent to your demand, on your solemn oath to quit Europe for ever, and every other place in the neighbourhood of man, as soon as I shall deliver into your hands a female who will accompany you in your exile.”

Up to this point, Frankenstein has thoroughly reconnected with his family, with Clerval. He dreams of marrying Elizabeth. But now he must absent himself again for his ghoulish task. “Company,” he says, “was irksome to me.” In a novel where isolation has only spelled disaster, such a statement comes preloaded with dread for what’s to come.

Frankenstein finds an island off the coast of Britain where he gets to work fashioning a second creature. He’s far underway when doubts begin to surface. Just as the first creature had free will, so will his second. And that presents a problem. What if this female wants nothing to do with the plan concocted by the creature? “They might even hate each other,” Frankenstein realizes and then rips apart the second creature he’s in the midst of making.

But the creature lurks nearby and observes. He knows of Frankenstein’s betrayal. With this final breach of faith by Frankenstein, the creature vows revenge and targets him directly where Frankenstein has just wounded him. “I will be with you on your wedding night,” he vows. He could have killed him right there but instead plans more cruel and calculating reprisals.

Before Frankenstein knows what has happened, a fresh tragedy strikes—one that cuts him to the quick. He knows exactly who’s at fault but can’t help but blame himself. Going all the way back to little William, he can see the bright red rope of culpability slowing cinching around is own neck.

In a final act of defiance, he decides to marry Elizabeth despite the creature’s grim promise. But, as with every other of his vain exercises, Frankenstein fails to count the cost.

He relates all this before passing the narrative back to Walton, who conveys it all to his sister—along with the final outcome of the story, which I leave for you to discover if you haven’t read it already. (Please do!) Suffice it to say, there’s a final misery inflicted upon Frankenstein which might double as a relief from a life soured by selfishness and solitude. That is one of Shelley’s many themes in the novel: Frankenstein creates in isolation and produces a creature of isolation—and thus also of desolation.

Returning to the opening point, you can find plenty of helpful advice about friendship in Seneca’s letters and other Stoic writings. But, believe me, you can’t find anything like Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon, share it with a friend, and 💬 discuss it in the comments below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

See also:

And make sure to tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, and discover the preorder bonuses!

I read this for the first time a couple of years ago and noticed how unlike popular culture portrayals of Frankenstein the book is - no lair-like lab where a mad scientist laughs maniacally over his creation, no bolts of electricity animating an assembled corpse. The book is actually much stranger than the familiar pop-culture caricature. Shelley's literary style has more in common with the writing of Austen and the Brontes, and her portrayals of domesticity are familiar to anyone who has read 19th century novelists. So the contrast is all the more stark in the scenes of desolation whenever the creature makes an appearance.

It’s more fun to read it as a prototype of The Talented Mr. Ripley, where there really is no monster except Victor himself whose incapacity to establish meaningful relationships manifests in closeted sexual frustration and homicidal reactions to recurrent shame. Otherwise, after some 17 years of teaching this novella, I’d have to admit it’s amateurish and overwrought, yet so emblematic of the zeitgeist and its contemporary analogues that it has become a must-read in spite of its deficiencies.