J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Against the World

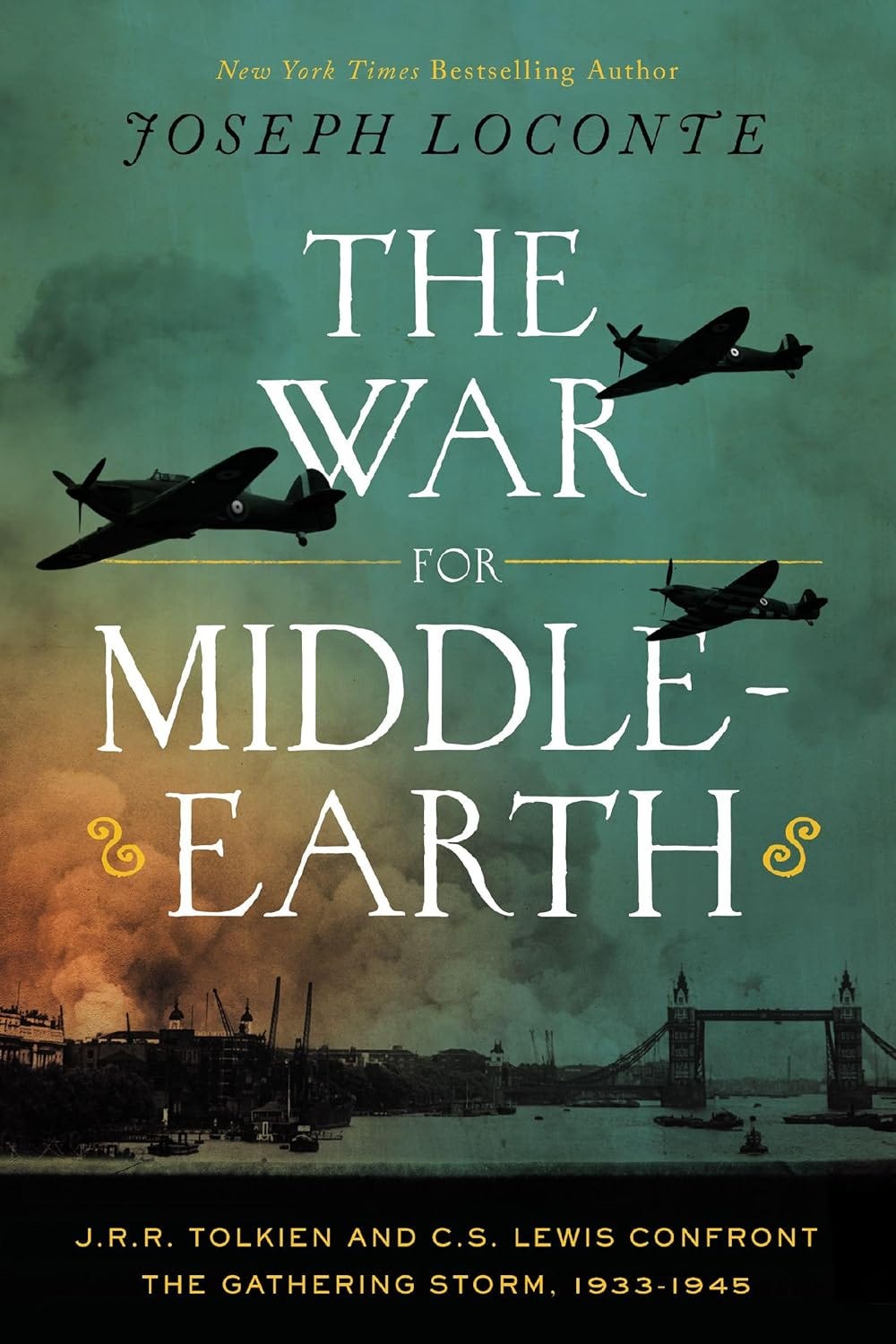

Reviewing Joseph Loconte’s ‘The War for Middle Earth: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Confront the Gathering Storm, 1933–1945’

As Nazi bombers sailed over the London skies, raining destruction upon the ground below, one of the countless buildings hit housed the second printing of The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien’s first foray into popular literature, neatly bound and awaiting new and eager readers. Book sales suffered along with everything else.

Books are, as I say in my new book The Idea Machine, bodiless teachers. They remind the learned, teach the ignorant, travel far, and cheat death. Authors, on the other hand? Death always wins, and authors are caught up in the exigencies of the moment, same as anyone else—cultural trends, economic changes, political upheaval, sometimes bombs.

Authors don’t outlive their times; rather, they are usually prisoners of it. Some, however, are brave and enterprising enough to stage a jailbreak. I give you Tolkien and his brother in arms, C.S. Lewis: products of their time but not its captives. And to make this introduction—not that they need it—I give you historian Joseph Loconte and latest book, The War for Middle Earth: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Confront the Gathering Storm, 1933–1945.

While they may need no introduction, Tolkien and Lewis do need this book to help us situate them in their own time and explain what motivated their writing.

A World Torn to Pieces

One of the last books I edited before leaving Thomas Nelson was Loconte’s prequel to this volume, A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914–1918. It helps answer the question: What happens when a whole way of life disintegrates before your eyes? World War I had that effect.

Loconte takes us into the wartime lives of Tolkien and Lewis. More importantly, he takes us into their postwar lives as well. How did they cope? How did they rebuild? And how did they help others do the same?

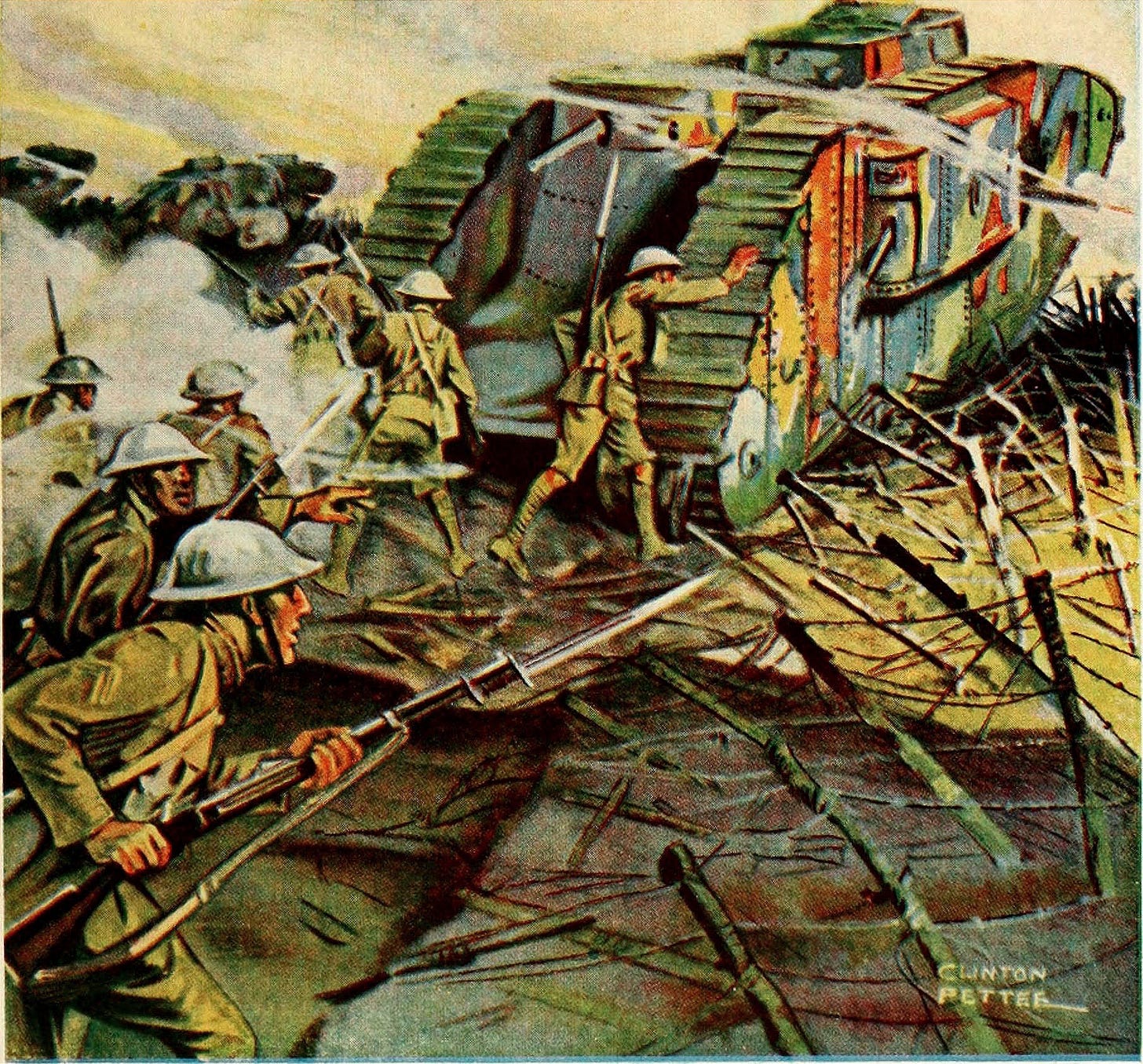

The trauma of the Great War is almost impossible to comprehend. More than 16 million were killed. That again plus another 5 million more were wounded. And those who recovered physically were often irreparably scarred in other ways. Shell shock, what today we would call PTSD, had longterm and devastating effects. Suicide and alcoholism often finished what bullets and bombs could not.

According to one contemporary study of shell-shocked Americans, “Seven years after the war less than 40 percent were regarded as functioning normally, and nearly 20 percent were found to be a burden to society.” Of that 20 percent, half were unemployable, and the rest weren’t much better. Michele Barrett recounts these and other statistics in her 2007 book Casualty Figures, noting that the British government paid over 2 million pounds a year to prop up those who could no longer prop up themselves—this at a time when social services were far less ambitious than they are in our day.

The whole enterprise was, as Loconte says, a “theft of youth.”

But the far-reaching crisis of faith may have surpassed all others. For those that endured it, the cataclysm and its aftermath was like the end of the world. What was left to believe in? Writes Loconte,

For the intellectual class as well as the ordinary man on the street, the Great War had defamed the values of the Old World, along with the religious doctrines that helped to underwrite them. Moral advancement, even the idea of morality itself, seemed an illusion.

Disillusionment and New Illusions

In a previous book The Searchers, Loconte contemplated the virtue of disillusionment, how it can serve—even with brutal and terrible imperfection—to sever us from harmful fantasies. In surveying the damage of World War I, he returns to that theme with the example of the pre-war Myth of Progress. This myth, says Loconte,

was proclaimed from nearly every sector of society. Scientists, physicians, educators, industrialists, salesmen, politicians, preachers—they all agreed on the upward flight of humankind. Each breakthrough in medicine, science, and technology seemed to confirm the Myth.

Christian ministers and theologians got swept along, baptizing and proof-texting all manner of bogus utopianism. And then it all went to hell. The preachers looked like fools or, worse, charlatans. When the survivors looked up from the devastation, many mistook the Myth for Christianity itself and tossed it in the garbage bin.

But the Myth of Progress didn’t die outright. With Christianity and its supposed virtues dead in the trenches, it took different shapes. Pointing to the failures the Old Ways, atheism, psychoanalysis, scientism, materialism, eugenics, socialism, fascism, communism, and disarmament all picked up the carcass of the Myth and tried invigorating its flaccid limbs with new energies. Each ism promised to clear the rubble of the Great War and lead its followers into a new and glorious future.

The promises failed to impress a couple of backward academics at Oxford, Tolkien and Lewis, both of whom served in the recent war and found the proposed remedies noxious and likely to bring more harm than health. Their rearguard action against these forces of “progress” comprise the story Loconte takes up in The War for Middle Earth.

It started, simply enough, by reforming the English syllabus at Oxford.

Common Cause

Education has long presented the narrow edge of whatever wedge activists seek to shove into society. Opposing modernism and hoping to rejuvenate earlier voices, especially those of the Middle Ages and early modern period, Tolkien and Lewis gathered likeminded Oxford faculty and drew a line in the sand at 1832. “The Old and Middle English parts of the curriculum were made more appealing to undergraduates, but the study of Victorian literature effectively fell by the wayside,” writes Loconte. “Jane Austen and Percy Shelley made the grade, but authors such as Emily Brontë and Charles Dickens were rejected.”

If that strikes us as somewhat arbitrary and overly conservative, maybe it was. But the dons felt they needed to draw the line somewhere so they could reinvest student energies in the riches of the English tradition fast being abandoned—such as Tolkien’s beloved Beowulf—and which they felt spoke to the modern predicament precisely because they stood so far outside it.

This was true for the classics more broadly and especially, of all things, fairy stories.“There is indeed no better medium for moral teaching than the good fairy-story,” Tolkien once said, holding aloft a copy of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. But both Tolkien and Lewis knew that teaching the old stories wasn’t enough. Was it a contradiction given their curriculum battle? Regardless, they also knew they must write their own.

“Tollers,” Lewis told Tolkien near the end of 1936, “there’s too little of what we really like in stories. I’m afraid we shall have to try and write some ourselves.” Tolkien agreed to write something on time travel and Lewis on space. Tolkien had already written The Hobbit; it was published a year later. Its astounding success derailed the time travel narrative; instead he would begin The Lord of the Rings. Lewis began work on the Space Trilogy, starting with Out of the Silent Planet.

All of this is known to anyone who picks up the books and looks at the copyright dates. What Loconte does is contextualize these and other writerly initiatives against the rise of Nazism across the Channel and bellicose Japan in the East. Tolkien and Lewis saw themselves as writing in defense of a Western and Christian tradition under attack from within and without. To them, the intellectual trends of the day—atheism, psychoanalysis, scientism, materialism, and the rest—all represented either well-meaning or malign misunderstandings of the world, posing a direct threat or making it impossible to respond to those threats.

In some sense, all work is a response to a problem. This was the problem the two dons faced, and it explains why they took up the work they did, both academically and for the popular press. On the academic side, for instance, Lewis sought to rehabilitate John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, beginning as a series of lectures, culminating in a book in 1942 (A Preface to Paradise Lost) while World War II raged. Why? “We have all skirted the Satanic islands closely enough,” he said, “to have motives for wishing to evade the full impact of the poem.” These earlier voices forced a reckoning in the present.

But what good would fairy stories do amid bombs and devastation?

The Resources Required

Tolkien responded to that question in a lecture, later expanded into an essay, “On Fairy Stories.” “Fairy stories,” summarizes Loconte, “offer Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, and Consolation.” No small things. These are, he says, “the resources required to live a fully human life.”

Fantasy allows the storyteller to flesh out “truths about the human story.” They awaken longing within the human soul and point us beyond ourselves—hence the need for Recovery, our “need to retrieve something of value that has been lost.”

Escape poses a problem for some. Isn’t it refusing to face reality? But Tolkien rejected escapism. “The writers of fantasy are,” says Loconte quoting Tolkien,

“acutely conscious of the ugliness of our works, and of their evil.” They look at the “progressive things” of twentieth-century European society—like factories, machine guns, and bombs—and properly reject them. They discern the patterns of the world that conspire to enslave us—and they point us toward freedom. Prisoners should not be scorned for trying to go home, he said, or for talking about topics other than jailers and prison walls.

That need for escape points us toward Consolation.

The oldest and deepest desire of mankind, Tolkien explained, is the Great Escape: to escape from death. Herein lies perhaps the greatest gift of a good fairy tale, the Consolation of the happy ending, what Tolkien called the eucatastrophe. It involves the undoing of a catastrophe, the reversal of a great evil. It is “a sudden and miraculous grace” that brings about deliverance, restoration, and renewal.

As powerful as these four features of fair stories may be, how could they oppose the forces arrayed against them? For Tolkien it came down to who told the more compelling story. Fascism and communism were, after all, nothing but false fairy stories. “They have made false gods out of other materials,” said Tolkien, enumerating the evils: “their nations, their banners, their monies; even their sciences and their social and economic theories have demanded human sacrifice.”

The archive of the Western tradition could be mined, as the Nazis had done, to present their fantasy. But they could also be marshaled against these vain imaginings. Better, truer stories were needed.

The moral cynicism of the day had, says Loconte, “produced a longing for moral beauty.” And this, says Loconte, “is one of the great achievements of The Lord of the Rings: to make the qualities of courage and fortitude deeply attractive to an otherwise skeptical generation.”

“When we have finished,” Lewis said about the narrative’s power, “we return to our own life not relaxed but fortified.”

The same could be said for Lewis’s Space Trilogy and The Screwtape Letters, books that exposed the inner workings of delusion rampant in their time. And that’s the gift that Loconte has given. These books still speak today in part because they spoke so powerfully then. Lewis and Tolkien took what was best in the Western tradition—what they fought at Oxford to preserve—and used it to critique and oppose the point-blank threat of what was worst in the Western tradition, its malformations and disfigured developments, prevalent in their day.

Can we manage the same today?

Thanks for reading! Want to add thoughts of your own? Comment 💬 below.

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Joel, a thousand thanks for your generous words here: You've captured, with rhetorical grace and power, the essence of what I set out to achieve with the book. Bravo!

Great reviews. "The Gathering Storm" in the title of one of these books is obviously a nod toward Churchill, whose 6-volume first-person history of WWII has that title. I'm nearly through Volume Two (Their Finest Hour) and I see Churchill's work as the other prong in the two-pronged look at what was happening to men's minds and actions during this time. (The other prong, what you are addressing.) Churchill was not an overt Christian, although he repeatedly referred to the importance of what he called Christian civilization. (I guess if you take Tolkein's and Lewis's fiction just on the basis of the words/vocabulary, they're not overtly Christian either.) Highly recommend Churchill's Pulitzer-Prize winning work with its deep insights and majestic language. I also highly recommend the book, God and Churchill, written by his theologian grandson.