Bookish Diversions: Lewis and Tolkien, Pen Pals

Their Creative Fellowship, New Explorations, New Discoveries, New Projects, More

¶ Pen pals. Does it strike anyone as strange that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien both lost their mothers when young? Lewis was just nine, Tolkien twelve. It’s at least curious—especially when you add other coincidences: Both men were injured in the Great War; both also loved the philological, mythological, and medieval. Stranger still, the pair ended up in Oxford at the same time and together helped inaugurate the literary genre we call fantasy. Neither were born in England yet rose as towers of English letters. The circles of their Venn diagram? Overlapping almost entirely.

We’re all perhaps somewhat familiar with the tale today, but a couple of recent biographical projects warrant attention: Award-winning illustrator John Hendrix’s new graphic novel The Mythmakers explores the friendship of Lewis (known to his intimates as Jack) and Tolkien (who Lewis dubbed Tollers).

My copy arrived last week. Sadly, I’ve only had time to browse. Still, others are raving. Here’s Meghan Cox Gurdon at the Wall Street Journal:

Mr. Hendrix has done an admirable job of explaining what went into the making of these two colossal figures and why we all still get so much out of the “portal of wonder” their writing opened.

And Lev Grossman at the New York Times:

makes a powerful case that if Tolkien and Lewis had never met, they would never have written their greatest works, the world would be a significantly less elfish place and 20th-century popular culture might have taken an entirely different course.

Hendrix subtitled his book “The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis & J.R.R. Tolkien.” The noun intentionally calls back to Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring, the first third of The Lord of the Rings. Another biographical project does the same. Angel Studios is in the early stages of production with Fellowship, a film which “tells the story of friends C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien as they write their classic novels.” News is otherwise sparse, but the release is currently slated for winter 2025.

As side note, it’s worth mentioning Philip and Carol Zaleski’s magisterial study, which earlier employed the noun to positive effect, The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams.

¶ Faith and place. Interest in Tolkien and Lewis ebbs but mostly flows, and we seem to be in a particularly flush time for various studies and projects concerned with both men. Lee Oser recently reviewed Holly Ordway’s religious and literary treatment, Tolkien’s Faith, as well as Simon Horobin’s new book, C.S. Lewis’s Oxford.

Oser seems particularly taken by Ordway’s scholarship and eye for convincing details coloring Tolkien’s independent and resolute character. “Tolkien, like a successful Gatsby, won [his future wife] Edith back after she became engaged to another,” says Oser.

He defied intense social pressure to enlist in order to complete his Oxford degree, before “bolting” into the army. He succeeded as a Catholic at overwhelmingly Protestant Oxford. He delayed the publication of The Lord of the Rings by several years, by “insisting that his epic be issued alongside another huge and unusual work (still incomplete), The Silmarillion.” He gave the responses “loudly in Latin” after the liturgy changed to English. If we turn to his astonishing lecture “On Fairy-Stories,” we find him standing up to Shakespeare, who gets mentioned by name, and to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who does not.

If Ordway focuses on how Tolkien’s faith shaped his life, Horobin’s book focuses on how place—especially the titular locale—shaped Lewis. It turns out, for instance, reluctance to leave his Oxford home and complicated extramarital relationship with the mother of a fallen brother-in-arms delayed an advantageous move to Cambridge University at Tolkien’s urging. Others have eagerly engaged with Horobin’s fascinating thesis.

¶ Jack be nimble. “Without Oxford, and the friendships it provided, there would have been no C.S. Lewis,” says Micah Mattix in his review of Horobin, expanding his scope to include how Lewis’s commitments at Oxford shaped his professional and personal life. Lewis, for instance, kept an insane schedule:

Lewis gave 24 hours of tutorials every week in addition to regular lectures (the standard at Oxbridge today is 8) and filled the rest of his schedule with literary and philosophical clubs.

His literary club the Inklings—which included Tolkien and at which the two shared works in progress with writers of similar sympathies—met twice a week, but that was only one of Lewis’s many groups, says Mattix.

He was a member of an Old Icelandic reading group for a time, and the Cave, “a group of English dons who gathered to discuss literary topics and School politics.” He went to a biweekly philosophical supper, ran an Elizabethan drama reading group every Tuesday night for students, hosted first-year undergraduates every Wednesday for “Beer and Beowulf,” and attended the biweekly Michaelmas Club, an undergraduate club that read papers on philosophy and literature.

Lewis attended chapel on weekday mornings on campus, dined with faculty in the evenings, and sometimes stayed on campus until the early morning hours. Amazingly, he somehow found time to tutor students, compose lectures, and write books—all the input and stimulation apparently necessary to do so.

It didn’t always serve him, of course. Lewis had no talent for the administrivia demanded by all the committees, meetings, finances, and departments he oversaw at various times. Lewis’s imaginative strengths dwarfed his followthrough and attention to detail. Predictably, he proved, as one colleague said, a “hopeless failure.”

At least he had a sense of humor about it. Lewis was, says Armand D'Angour in his review of Horobin for The Critic,

required to write an official account of his term, and did so as a five-act drama in blank verse entitled “The Tragi-Comicall Briefe Reigne of Lewis the Bald.” It survives in the college archives, as does a large corpus of his letters and book drafts written in his neatly slanted handwriting. . . .

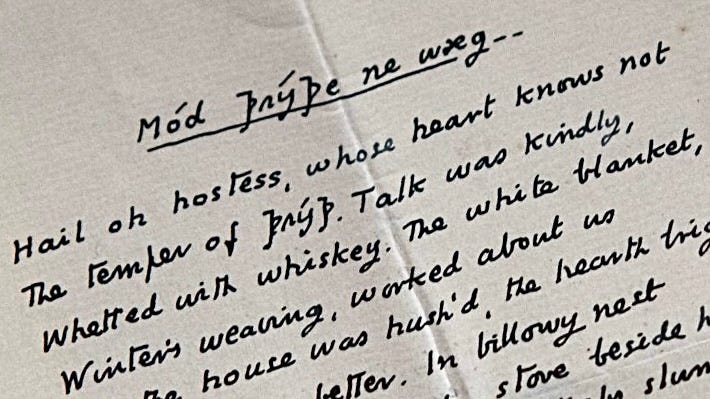

¶ Booze, blankets, and Beowulf. Given the duo’s massive popularity and all the decades over which enthusiasts might comb and sift their archives, it’s remarkable that new discoveries still come to light. But they do. While recently conducting some research in the Tolkien-Gordon Collection at Leeds University Library, scholar Andoni Cossio noticed a previously undiscovered poem by Lewis.

The twelve-line, thank-you verse acknowledged the hospitality of friends Ida Lilian Gordon and E.V. Gordon following a wintertime stay by Lewis’s at their home, likely in 1935. “The discovery of this hidden treasure made me feel elated,” said Cossio. “I was astonished to find that this poem doesn’t appear in any of [Lewis’s] collected works.”

The Gordons were both medievalists and would have appreciated Lewis’s playful but otherwise obscure use of Old English in the poem, titled “Mód Þrýþe Ne Wæg” and written on Magdalen College stationary. Tolkien likewise counted the Gordons as friends and co-edited his popular Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with E.V. Gordon.

“Hail oh hostess, whose heart knows not/The temper of Þrýþ,” Lewis begins. Says Cossio,

Þrýþ, according to Lewis and Tolkien, is the name of Offa’s evil queen in the Beowulf poem. . . . Mód Þrýþe Ne Wæg is translated very poetically within the poem by Lewis as “whose heart knows not the temper of Þrýþ,” which means that Ida Gordon is the exact opposite of Þrýþ, that she was a good human being.

More on the poem here and here.

Writing in alliterative verse known from such Anglo-Saxon poems as Beowulf, Lewis praises Ida Gordon’s hospitality with reference to whiskey, blankets, a hot stove, bright fire, and a quiet night. The poem is unsigned, but Lewis refers to himself as the author under the name “Nat Whilk,” a pseudonym he employed when publishing poems in Punch magazine. The name’s a tease, Old English for “I don’t know who” or “anonymous.” Lewis also used the initials N.W. when first publishing A Grief Observed.

It’s worth saying Lewis wasn’t always so kind.

¶ “Loud-mouthed bully.” As part of his research, Simon Horobin made discoveries of his own, including seven previously unknown poems by Lewis, six written inside his personal copy of H.C. Wyld’s 1921 book, A Short History of English, and final one in another book by Wyld. Lewis was no fan. He penned the poems in modern English, Old English, French, Latin, and Greek and singed the page as he wrote.

In one he refers to Wyld as a “loud-mouthed . . . bully,” describing his way of browbeating those who spoke the King’s like rogues. Translated from Latin, another reads:

Like the peace of God that keeps our hearts and minds, this book “passeth all understanding.”

¶ Different song, different verse. Anyone who’s read The Hobbit or Lord of the Rings knows Tolkien also wrote poetry. What they might not realize? He saw himself as something of a poet, desired to be regarded as such, and wrote piles more than intermittently appears in his fiction. Now, thanks to the editorial ministrations of Christina Scull and Wayne G. Hammond, all those verses have finally been collected in one three-volume set.

You can tell by the dates covered by the volumes he was most active in his earlier years: Vol. 1, 1910–1919; Vol. 2, 1919–1931; and Vol. 3, 1931–1967. Holly Ordway, author of Tolkien’s Faith mentioned above, has a helpful review here. See also Dalya Alberge in the Guardian and Tom Emanuel in The Conversation.

¶ Inside and outside the Boxen. While Tolkien and Lewis continue to see major screen adaptations of their work—most recently Amazon’s Rings of Power and Greta Gerwig’s upcoming Narnia reboot—smaller opportunities exist for the plucky.

Chalkdust, a startup animation studio in Atlanta, Georgia, drew attention when it announced plans to animate Boxen, the imaginary world C.S. Lewis and his brother Warnie created when they were children. Variety reports the first season has been successfully financed.

Nor are we near the end of what the more creative among us might take as inspiration for their next project. Choreographer Silas Farley and composer Kyle Werner found the idea for a ballet hiding within the pages of Lewis’s book The Four Loves. “The text,” says reporter Emily Belz,

examines four classically Greek categories: storge (familial love), philia (friendship), eros (romantic love), and agape (divine love). Werner and Farley thought the four loves mapped well onto a traditional four-movement symphony, so that’s what Werner composed in the space of a few months.

In Farley’s ballet, the storge movement depicts a mother-daughter relationship, the philia movement depicts two male friends, the eros movement depicts a male and female couple, and the agape movement depicts the Trinity, bringing the loves from the other movements together.

Ironically, perhaps.

¶ Philia broken. Sadly, the philia between Lewis and Tolkien cooled and the Venn diagram eventually pulled apart. Relational and religious differences played a big part, possibly artistic differences as well; they certainly had them. One example: Lewis assumed the world of Narnia was flat, not spherical like a globe. Tolkien played with the idea for his own world but rejected it because it was “astronomically absurd.” Lewis found such absurdities amusing.

The two old friends remained mutually supportive, even though the distance between them proved both real and seemingly unbridgeable. Still, while the two remained close, they were a force.

“Most don’t realize how essential their fellowship became,” says John Hendrix in an interview with Print. “Each man gave the other the precise gift needed to complete their own story. Tolkien gave Lewis the freedom to love his imagination. Lewis gave Tolkien sheer encouragement, without which he never would have completed the 17-year journey of writing Lord of the Rings.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

A very helpful update; thank you. I have just read most of Lewis's religious works (having consumed Narnia as a child more times than I recall). I very much recommend A.N. Wilson's biography, which is beautifully written, fair minded, and not fawning. Had it not been for Tolkien, it is very likely that Lewis would not have become a Christian - or perhaps the conversion would have been much later and quite different. Lewis and Tolkien actually met late in life once more - the Venn diagram did recompose itself for a brief afternoon - though it was evidently a difficult coming together. One thing that baffles me is that the pub where the Inklings often met - The Eagle and Child, in the middle of Oxford - has been closed since COVID. Given the vast amount of money sloshing around, courtesy of their works, and given that tourists would happily queue up to sit and have a beer there, I cannot understand why the premises haven't been snapped up. It would be a licence to print money...

What an absolutely awesome and inspiring read. Thank you SO much. It caught my attention because I had randomly mentioned Lewis and Tolkien in a conversation yesterday. I told my husband I needed less of “The Diplomat” (a show he loves) and more of the fairy fantasies of George MacDonald as I work on my own novel. 😃