Giving Thanks for C.S. Lewis

It’s the 60th Anniversary of His Death: Here’s to His Life and Ongoing Influence

November 22 this year marks the sixtieth anniversary of C.S. Lewis’s death. I can recall reading a newspaper obituary about Lewis my grandmother kept. She preserved the entire paper. The event was buried in the back—just a few inches of text. The rest of the paper, or at least the majority of it, was dedicated to reporting the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Both men died the same day. Coincidentally, they both answered to “Jack.” Though popular, this Irish author and academic couldn’t rival America’s departed head of state. Coverage of Lewis’s passing was swamped by pages and pages of copy about the death of Kennedy. Naturally, that’s why my grandmother kept the issue.

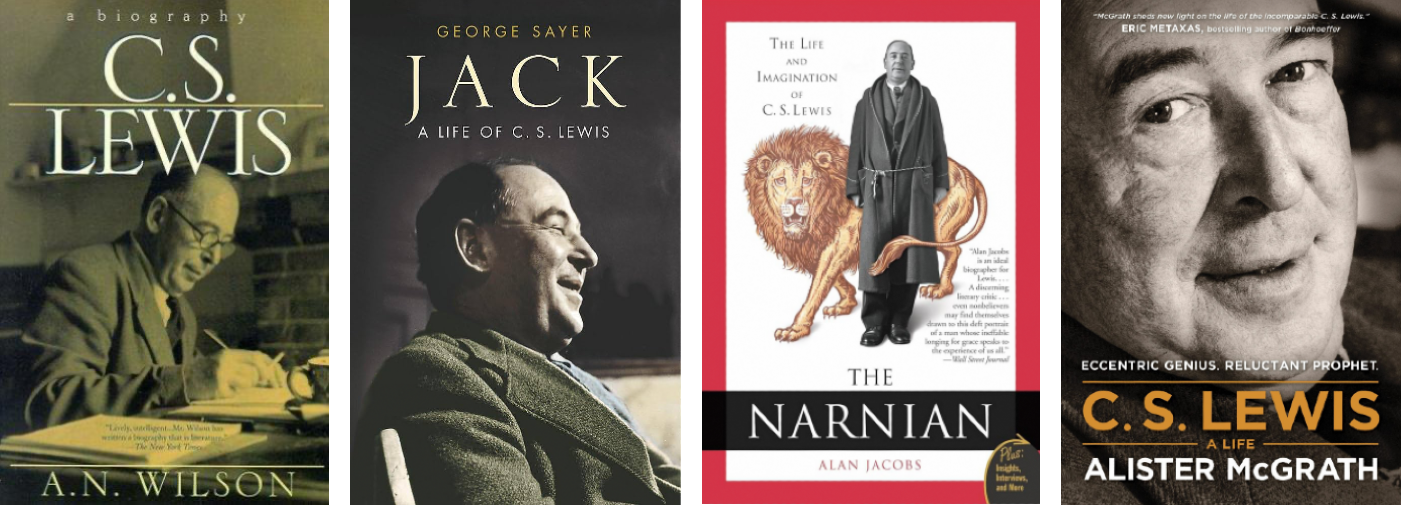

Reflecting on the date and what it signifies, I spent some time reading about Lewis’s final years. Biographies by A.N. Wilson, George Sayer, Alan Jacobs, and Alister McGrath offered helpful windows into his waning days.

Bad Health, Good Spirits

A bachelor until late in life, Lewis eventually wed, but the marriage was brief. His wife, the American Joy Davidman, died of cancer in 1960 after just four years of marriage. Following her death, the grieving Cambridge professor found himself a single dad to Joy’s two boys.

Then, some eleven months later, Lewis began experiencing difficulty peeing. Doctors concluded that his prostate was significantly enlarged and that his kidneys were infected, spreading toxins through his bloodstream and causing cardiac trouble. His condition didn’t go unnoticed by friends. One recalled that he looked “very ill.” Another said he appeared “unwell.”

Besides giving him blood transfusions—the only solution before dialysis—doctors put Lewis on a low-calorie diet and ordered him to quit smoking. He disobeyed. “If I did [comply], I know that I should be unbearably bad tempered,” he told George Sayer. “Better to die cheerfully with the aid of a little tobacco, than to live disagreeably and remorseful without it.”

Sayer says that Lewis “never lost his sense of humor.” Indeed, he was famously good natured, even amid dire circumstances. On July 15, 1963, he suffered a heart attack and slipped into a coma. Friends feared the worst; some came and prayed; a priest gave the sacrament of extreme unction. Amazingly, an hour after the sacrament, Lewis awoke, revived, and asked for a cup of tea.

True to form, he found a joke in it. “I was unexpectedly revived from a long coma,” he wrote Sister Penelope, an Anglican nun with whom he frequently corresponded. “Ought one honor Lazarus rather than Stephen as the protomartyr? To be brought back and have all one’s dying to do again was rather hard.”

The joke reflects a more serious poem Lewis had written a few years prior, “Stephen to Lazarus”:

But was I the first martyr, who

Gave up no more than life, while you,

Already free among the dead,

Your rags stripped off, your fetters shed,

Surrendered what all other men

Irrevocably keep, and when

Your battered ship at anchor lay

Seemingly safe in the dark bay

No ripple stirs, obediently

Put out a second time to sea

Well knowing that your death (in vain

Died once) must all be died again?

Though his health improved some, Lewis resigned his position at Cambridge and settled into life at his home, the Kilns.

Walls of Books

Though Lewis began suffering acute delusions at this time, Jacobs records another story that captures his humor and good spirits. Following his resignation, Lewis sent his recently engaged secretary, Walter Hooper, to collect his things from his rooms at Cambridge—including an extraordinary number of books for which the Kilns had little available room. Back at the house, writes Jacobs,

some comedy ensued when Lewis talked Hooper into building a wall of books around the sleeping body of Alec Ross, Lewis’s live-in nurse, who had chosen the wrong time and place to take a nap.

Books always formed a key part of Lewis’s life, just as Lewis’s books have now long formed a key part in the lives of many others. They’ve been part of my mental atmospherics for more than three decades now.

I read the Space Trilogy in high school and my first year in college, followed by Mere Christianity and The Screwtape Letters. I read Till We Have Faces then as well and have come back to it several times since. Somewhere in that period I also read Sayer’s biography, Jack, for the first time.

A friend’s dad was a minister and had a dust-jacketless hardcover of Lewis’s God in the Dock he’d given his son. In those dark days before Amazon and AbeBooks, this was a treasure of inestimable value. I traded my friend a nearly-complete set of Charles Williams’s novels to secure the all-important book of essays.

Williams was a close friend of Lewis and wrote a series of eerie novels, characterized as supernatural thrillers. One, The Place of the Lion, imagined Plato’s forms breaking into the material world and influenced Lewis’s creation of his most memorable character, Aslan.

Some years later I wanted to reread Williams’s novels. I lucked out and found the set at a used bookstore. I’ve since given them away again. But I had—and still have—the pearl of great price, Lewis’s God in the Dock, and have been able to make much use of it. In time I found and purchased many other Lewis volumes: The Four Loves, Christian Reflections, Studies in Words, Miracles, The Weight of Glory, Present Concerns, and more.

The Narnia stories actually came late for me. I only read them in my thirties. It’s the same story with Reflections on the Psalms and The Discarded Image, which I first read some thirteen or fourteen years ago.

I haven’t checked, but I would guess I quote Lewis more than any other single author. I have more books by him than any other (except maybe St. Augustine). And I keep returning to them. I’ve probably read Till We Have Faces five or six times at this point. I particularly enjoy rereading his essays.

Lewis was always a serious rereader. “I can’t imagine a man really enjoying a book and reading it only once,” he once wrote a friend. Rereading “is one of my greatest pleasures.”

Final Pages

Holed up at the Kilns in those final months, Lewis reread the Iliad and other books. Sayer lists not only the Iliad and the Odyssey but mentions that he read them in Greek, that he read the Aeneid in Latin. He also read “Dante’s Divine Comedy; Wordsworth’s The Prelude; and works by George Herbert, Patmore, Scott, Austen, Fielding, Dickens, and Trollope.”

Surrounded by his books, Wilson says that Lewis “remained . . . propped up in the very room where Joy had spent so many heroic hours suffering.”

And then he joined her.

It was Friday, November 22. Lewis was cheerful but had a hard time staying awake. He ate breakfast, got dressed, answered some letters. After lunch, his brother Warnie “suggested he would be more comfortable in bed, and he went there.”

Warnie took him tea at four. An hour and a half later he heard a crash. Lewis had collapsed at the foot of his bed. Unconscious, as Warnie recorded, “He ceased to breathe some three or four minutes later.”

Lewis wrote dozens of books, some of profound literary, cultural, theological, and psychological insight. He never imagined the lasting influence he would have. “After I’ve been dead five years,” he told his friend Owen Barfield, “no one will read anything I’ve written.” Indeed, after quitting his post at Cambridge, he worried about dwindling funds; he didn’t see how his royalties would last.

He needn’t have worried. Lewis’s books have long outlived him. There’s a story there, too, of course. I tell it here. In the meantime, there’s no better way to give thanks for Lewis’s life and work this time of year than pulling a favorite volume off the shelf and settling in between the pages.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

“Better to die cheerfully with the aid of a little tobacco, than to live disagreeably and remorseful without it.”

That alone was worth the price of admission. Thanks.

After speaking at Wheaton College, I headed over to the Wade Center that houses many things from the private collections of Lewis, Tolkien, et al. I asked to see some of the books Lewis read. They brought up three including one of my favorites: Paradise Lost by Milton. Lewis took tons of notes. His marginalia flooded the pages. He used a pencil and wrote in very neat lines. If a man who gained a triple-first at Oxford thought it was important to engage books in this way, it greatly encouraged me to continue to do so myself.