Bookish Diversions: Down the Memory Hole?

Not if We Can Help It: Tom Wolfe, Orwell’s Forgotten Wives, Jorge Luis Borges, Digital Preservation, More

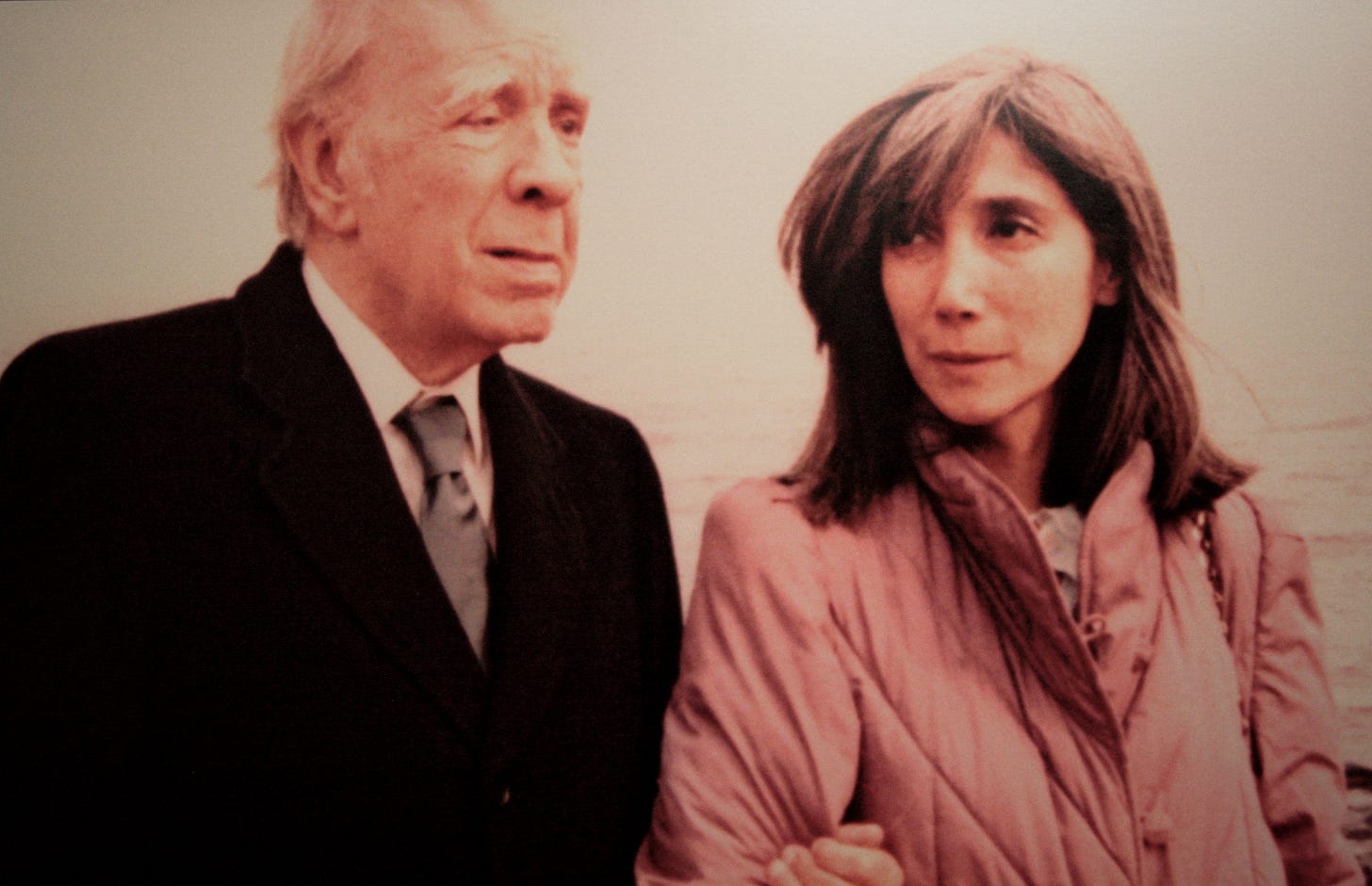

¶ A man in full. “You feel there’s certainly an emptiness in your own life because he filled so much of it with his wisdom and his writing,” said writer Gay Talese, reminiscing about his friend, the journalist and novelist Tom Wolfe. “I don’t want to be disrespectful of the departed, nobody does, but a lot of writers you don’t miss.” For Talese, Wolfe, who died in 2018, is different—and he’s not alone in his assessment.

Most writers aren’t missed. I recently looked at the tendency for us to lose track of them and their work. Even before their permanent departures, they slip unseen down the memory hole. Rare are the writers who, like Zora Neale Hurston or F. Scott Fitzgerald, manage to claw back into the public consciousness once lost to obscurity, rarer still those like C.S. Lewis who never really experience a dip in attention.

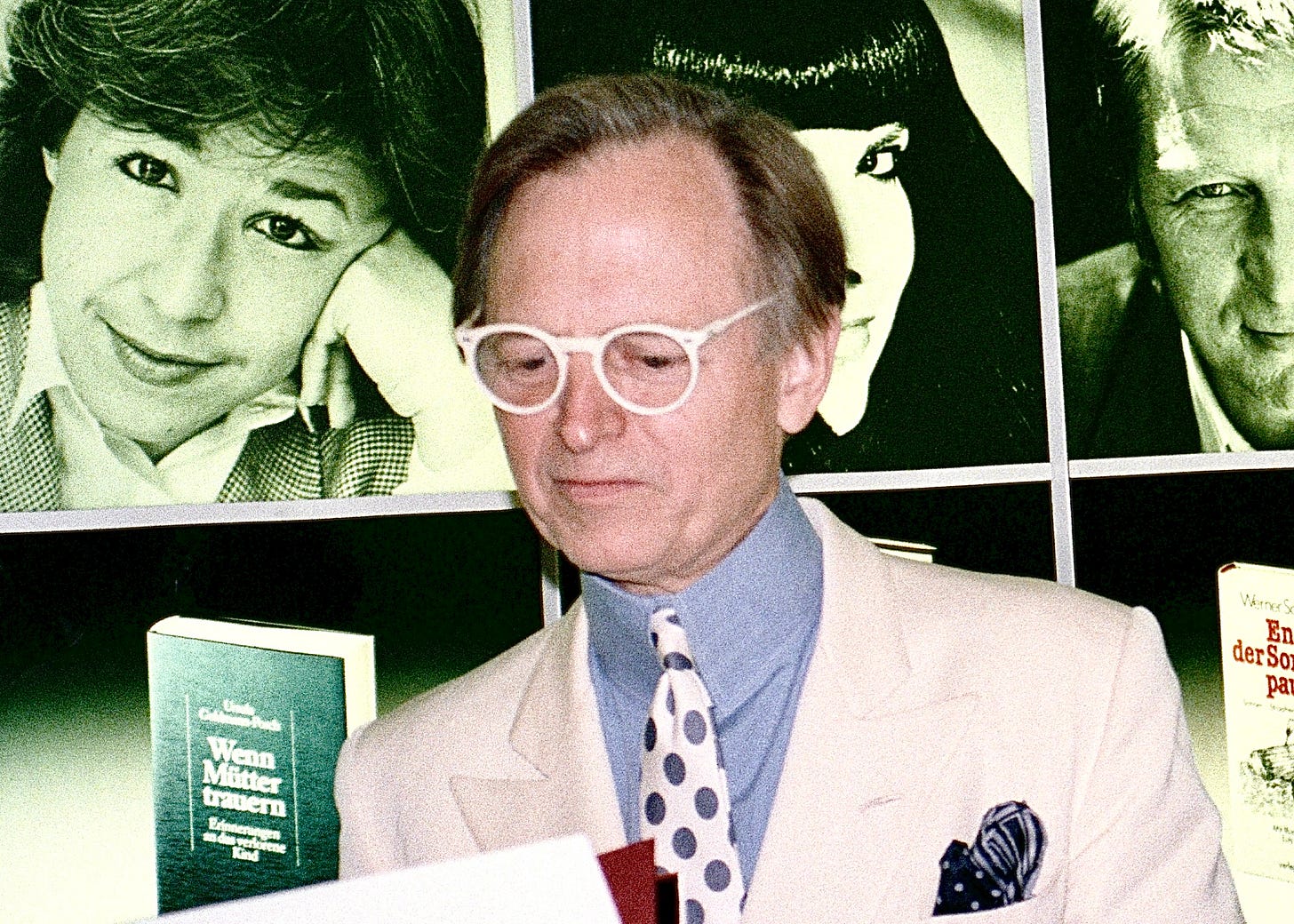

It’s still too early to tell, but Wolfe could end up like Lewis. He remained at the center of the public mind from his early career until the day he died. And he shows no sign of slowing five years after his death. Just the opposite.

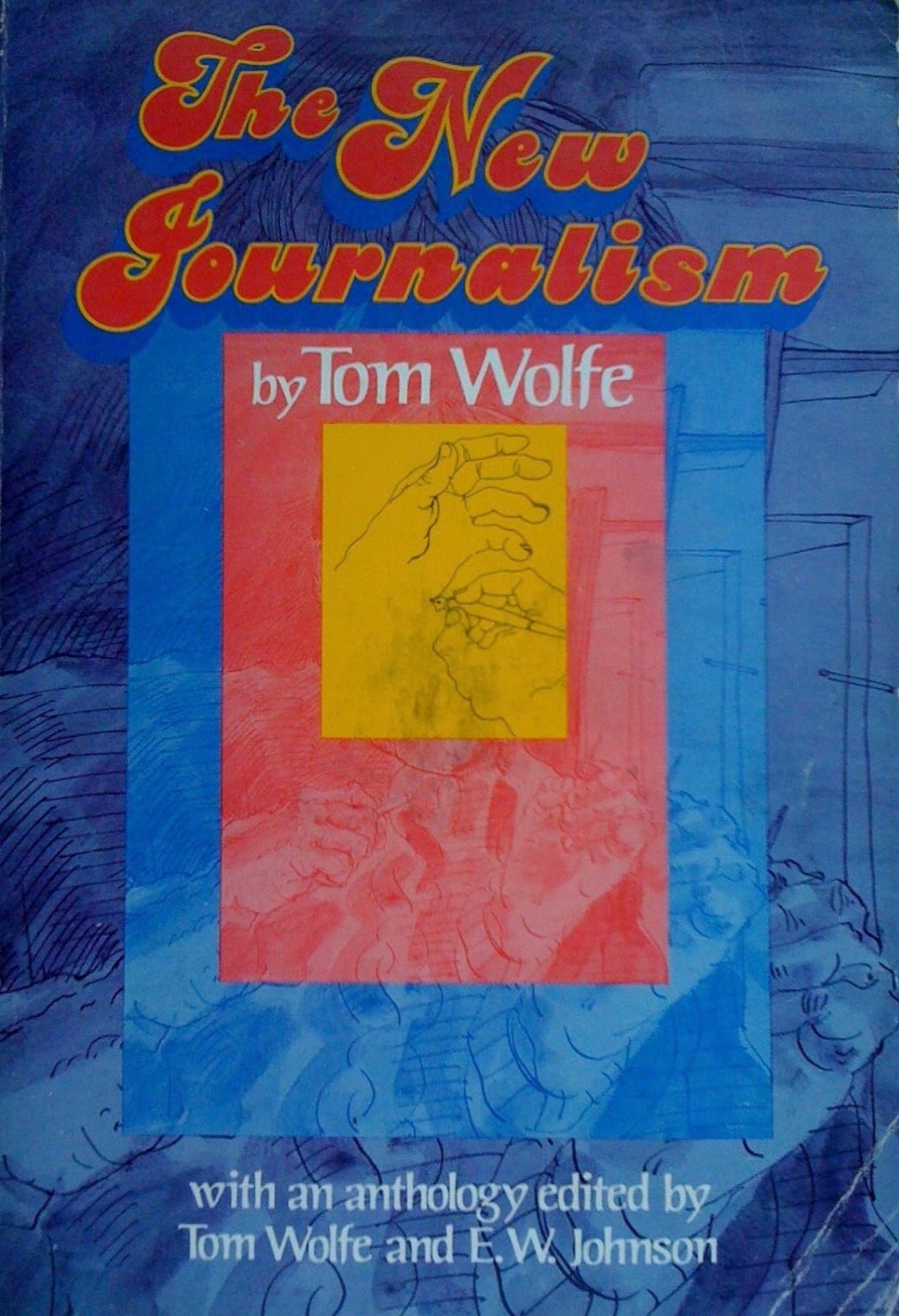

“Tom Wolfe is having a moment,” write Peter Stevenson and George Gurley at Airmail, citing upcoming television adaptations of two of his novels, A Man in Full from 1998 and The Bonfire of the Vanities from 1987, as well as a new documentary directed by Richard Dewey entitled Radical Wolfe, based on a 2015 Vanity Fair profile by Michael Lewis. What was so radical about Wolfe?

Working in the 1970s at the bleeding edge of the so-called “New Journalism”—a phrase he coined—with such writers as Talese, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Hunter S. Thompson, and others, Wolfe turned his journalistic sights on subjects often overlooked but which he covered with irrepressible, incandescent prose.

Nothing proper, just wildly popular. If it was established, trendy, metropolitan, and sophisticated, he would pummel it to a pulp between sheets of paper and a barrage of typewriter keys. And the established, trendy, metropolitan, and sophisticated—at least some of them—seemed to love him for it, along with the rest of America, as he produced a series of successful articles, nonfiction books, and novels. A sampling:

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), a look at Ken Kesey and his LSD-evangelizing Merry Pranksters following the success of Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers (1970), half of which was based on a legendary party hosted by composer Leonard Bernstein for the Black Panthers.

Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine (1977), which featured his sendup of the New Age’s cocktail of self-serving spirituality and materialism, “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening.”

The Right Stuff (1979), still the best nonfiction treatment of the U.S. space program’s early days.

Plus two additional novels: I Am Charlotte Simmons (2004), a pointed critique of university life and our malleable identities, and Back to Blood (2012), about the immigrant experience in Miami.

By the 1990s critics could more easily dismiss him as a conservative, and did, but he wasn’t really. If he was, it was more by temperament than ideology. He was friends with feminist icon Gloria Steinem and lived most of his exuberant life among his choicest targets, getting ideas for stories at their exclusive parties—like the one at Bernstein’s.

“Despite being lampooned, New York society loved him even more,” say Stevenson and Gurley. Proof? They quote Wolfe’s wife, Sheila Berger, a former magazine art director: “The invitations kept coming.”

Wolfe’s career thrived on it all. Writing at City Journal, John Tierney considers why. The media, he says, was less polarized back then and open to broad cultural critique. Wolfe also avoided partisan politics, which meant it was harder to peg and dismiss him. Beyond that, says Tierney,

Nobody else combined his fearless contrarianism and erudition with his eye for spotting just the right absurdities and status details. Nobody else had those gifts—and, most important, nobody else could turn out such glorious prose. Agree with him or not, you couldn’t stop reading.

Stevenson and Gurley mention an additional reason, echoed by Tierney. Originally from Richmond, Virginia, Wolfe never considered himself culturally part of the New York he inhabited. The duo quotes Talese:

I knew a lot of Southern writers who came to New York. . . . Most of them wanted to blend in as New Yorkers. But Tom never tried to blend in. He was a visitor. He saw the city with a kind of detached air of amusement and a certain disregard for its posturing. He stood apart from the city, and he saw it from a distance with a severity of vision.

He was in the city but not of it, and that distance provided the critical perspective necessary to become Tom Wolfe, forge a legendary career, and avoid the memory hole—at least for now.

Owen Gleiberman has a helpful review of Radical Wolfe at Variety and Tierney talks with director Richard Dewey about the film at the 10 Blocks podcast. I can’t wait for wider distribution so I can watch it myself.

¶ The women behind the men. One fascinating detail from Stevenson and Gurley’s Wolfe profile? The role his wife played in his work, especially the early stages of a project. “At the parties,” they write,

Sheila did stealth reporting. “It was hard for Tom to observe everything because he was the center of attention,” says Sheila. “I was able to sit on the sidelines and observe things.” And when they got home—a town house on East 62nd Street—they would share their impressions. It was material Wolfe would use, concocting terms such as “Masters of the Universe” and “social X-rays,” in The Bonfire of the Vanities, his 1987 best-seller.

Women attached to famous men are often the first to slide down the memory hole, even if their work is essential to the production of those famous men. The term was coined by George Orwell in his novel, 1984, and—as a new biography shows—ironically fits the fate of his first wife, Eileen Blair. I’ve just completed the book, Anna Funder’s Wifedom, and plan to review it this coming week.

Surprisingly, Eileen was instrumental in the shaping of Animal Farm, both conceptually and editorially. She worked as the couple’s sole breadwinner for extended periods to allow Orwell freedom to write, and she typed and corrected more of his manuscripts than anyone could probably count—not to mention all her domestic services. Orwell never did give Eileen ample credit; in fact, he seems to have actively effaced her at times. She died prematurely and would be all but lost to history were it not for one prior biography and Funder’s own efforts at excavating her life.

Orwell’s second wife, Sonia, was also instrumental in shaping and ensuring his legacy. Though only married fourteen weeks, Sonia was entrusted with Orwell’s literary estate after his long-looming, creeping death by tuberculosis. As Stacy Schiff writes,

Sonia Orwell had an enormous capacity for and dedication to work. . . . Primarily, she devoted herself to the thankless task of literary executorship. Her critical volumes of Orwell[‘s essays, journalism, and letters] stand as testimony to her editorial talents, which had been questioned only by those men who could not seem to abide the coincidence of talent and beauty in the same tamperproof package.

While Eileen was quiet and reserved, Sonia was loud and flamboyant, happy to stir up fun or opposition wherever she turned. But I think it’s safe to say without these two strikingly different women there would be no George Orwell—certainly not the Orwell we ended up with. Thanks to their efforts, even if not always appreciated or remembered, Orwell dodged the memory hole.

¶ Assuming control. When the celebrated Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges died in 1986, his young wife María Kodama took charge of his literary estate and worked doggedly to ensure his legacy. Literary editor Alejandro Chacoff described her as

a kind of workaholic focused only on the obsessive administration of her dead spouse’s estate for almost four decades. I often recall the primary objectives of the International Jorge Luis Borges Foundation, which she founded in 1988, two years after his death: “to disseminate the work of Jorge Luis Borges, contribute to its knowledge and promote its correct interpretation.”

I’ve told part of the Borges and Kodama story here before, including the her own failure to name an executor of the estate before her death earlier this year, throwing her beloved husband’s legacy into question. What I only alluded to then was the controversies around Kodama’s oversight of Borges’s work, something Chacoff explains in full.

Focusing on the objective of the Borges foundation cited above, he writes,

The most important part of the phrase—which appears in capital letters on the foundation’s website—is “correct interpretation,” underscoring Kodama’s belief that there is a unique key to understanding the work of Borges, and that as sole heir, she had this key.

Consequently, Kodama held a death grip on her literary property, suing anyone who dared transgress her desired memory of Borges, including many wholly legitimate efforts by scholars and other authors to interact with his writing. There’s no reason to think Borges himself would approve of the strictures his widow placed around his legacy.

The story is a reminder that avoiding the memory hole comes with tradeoffs. The dead don’t have opinions, unless clearly stated in wills and testaments. But literary estates and their executors have ongoing interests that can deviate from their authors’ original desires, sometimes dramatically. What, for instance, would Roald Dahl or Ian Fleming think about recent efforts to sanitize their books for modern sensibilities? We can’t know, yet the revisions to their books continue regardless.

Since her death, the rights to Borges’s work now sit with Kodama’s nephews. It’ll be interesting to see how they manage his legacy going forward.

¶ Transient media. The primary challenge in skirting the memory hole is preservation. There are, for instance, no critical editions of Borges’s work because he didn’t keep copies of his revisions, so those nuances and developments in his writing are now lost to time. Such archival materials are essential for creating fully rounded pictures of authors and their writing—consulting letters, comparing iterations and drafts, analyzing documents, not to mention fleshing texts with images, audio, video, and so on.

Filmmaker Richard Dewey couldn’t have made Radical Wolfe without access to Tom Wolfe’s papers, now deposited at the New York Public Library. As he explained to John Tierney,

I always prefer, if possible, to have the main character tell their own story. I didn’t want to rely on a narrator, so the first thing we did was build this repository of archival footage of Tom on talk shows and being interviewed on the radio, and thankfully he had given interviews almost since the beginning of his career, and we assembled about 150 hours of archival footage and about 4,000 still photos. And that gave us the confidence that Tom could really tell his own story and how he came up with these ideas and in many cases, persevered and figured out the stories, and we wouldn’t have to rely on a narrator, but it was a lot. 150 hours and 4,000 photos is a lot to sift through to find the nuggets.

It’s an astonishing feat, actually, but one only possible because of the painstaking prior act of saving, collecting, and preserving all that mixed media. And the sobering reality? Media is not as fixed and certain as it might seem. Such preservation efforts are prone to failure.

The books on your Kindle, for instance, can you be sure they’ll be there tomorrow? In a fascinating, in-depth piece for Reason magazine on the challenges of cultural perseveration, Jesse Walker mentions the 2009 instance of a vendor selling an unauthorized ebook of George Orwell’s 1984. Maybe you remember the story or can see where this is going. “Amazon,” says Walker, “reacted by dispatching even some purchased copies to the memory hole.” Poof! Gone. Like it was never downloaded in the first place.

Digital archives are subject to loss, even manipulation, something worth contemplating as universities and other institutions wholesale swap physical media for digital collections, as the Vermont State Colleges System did earlier this year.

¶ Conjured from the distant past. And then something astonishing happens when you least expect to reverse the tide of inevitable oblivion. A British specialist in illuminated manuscripts has discovered a long-lost, eighth-century Old English copy of the Gospel of John translated by the Venerable Bede, along with the saint’s actual handwriting. There it is, back up from the bottom of the memory hole! At least probably. “You haven’t got a smoking quill,” admitted the scholar. “It doesn’t say ‘Bede’. But put all the evidence together and I think this is as good an argument as has been advanced.”

Memory is an enterprise, usually faulty, but sometimes surprisingly fruitful.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below, punch the restack icon 🔄 and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

What a great post. I have loved Tom Wolfe since I read Electric Kool Aid Acid Test in high school. Even at that young age, I could tell Wolfe wasn't impressed with the childishness of the Merry Pranksters. And whenever I see Al Sharpton today, I think of Reverend Bacon from Bonfire of the Vanities.

As much as possible, I use my Kindle as an eReader only. I buy inexpensive digital collections of classics from delphiclassics.com, or download free copies from standardebooks.org. I don't trust Amazon to preserve original versions. Last night I reread Flannery O'Connor's short story, "Revelation", and I wondered how long that will remain available with its repeated use of racial slurs -which are used to make the main point of the story - but that is something that a lot of people today won't get.

I have to admit that I have never read anything by Tom Wolfe, although I am certainly familiar with his name (there is simply only so much time to read and there are still so many classics to get through...) and the background you provide sounds fascinating.

I have profound skepticism of digitizing books to "preserve" them, for the exact reason you note here. I indeed collect physical books so that my children can have them for their own home libraries once they move out. In a news piece I read about the Peel District School Board here in Ontario, I was horrified to learn that they emptied the school library of all books that were written before 2008 (including Anne Frank!) because of "lack of diversity". They did not even pass them on, but instead sent them to the landfill. Digitizing books under authorities who decide what should be read is a dangerous endeavor that will most certainly doom countless books down the memory hole.