Bookish Diversions: After the Final Chapter

A Literary Estate in Limbo, When Authors Regret Their Books, Borges and Buckley, More

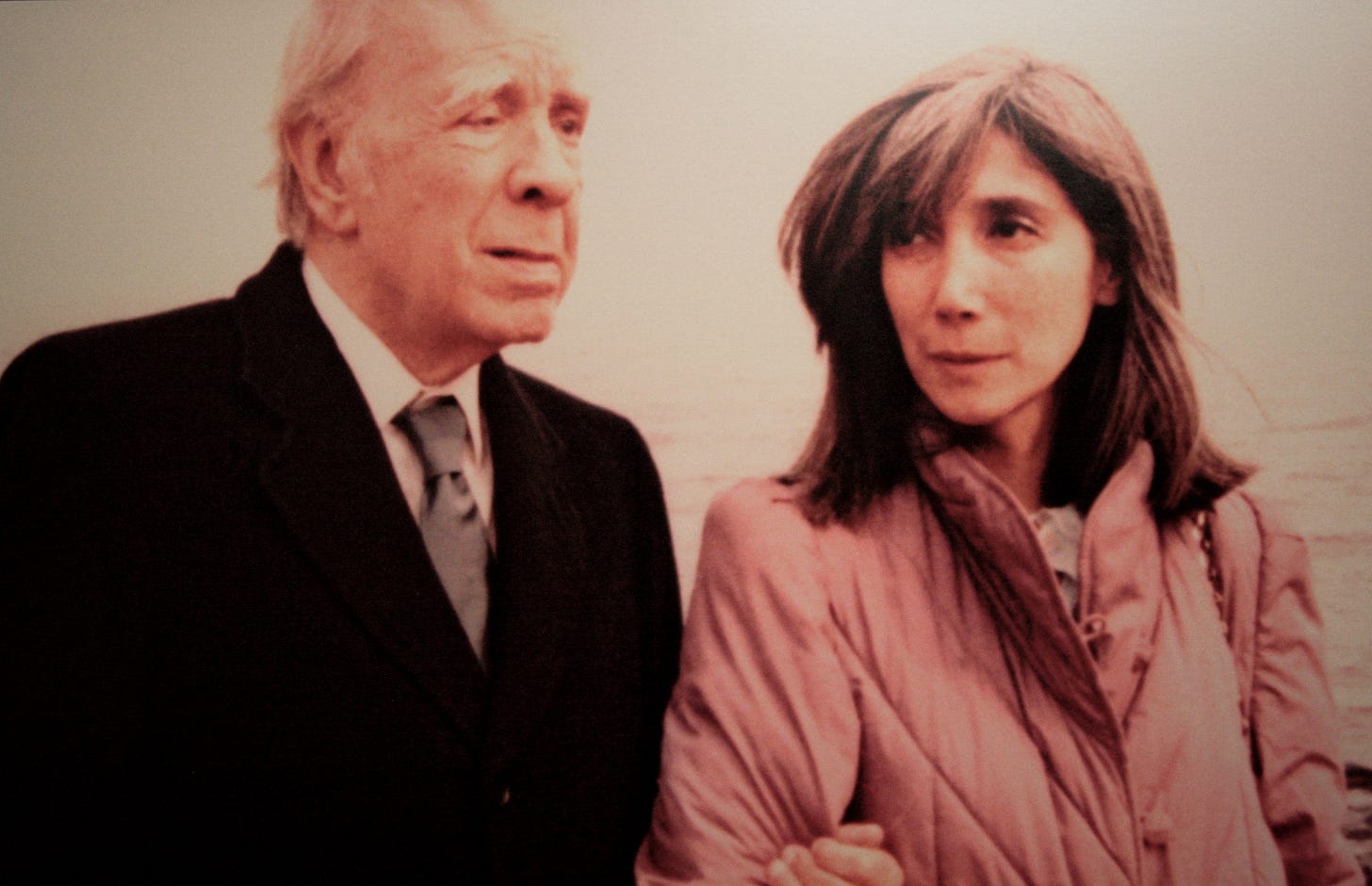

¶ Will or no will. María Kodama said she planned to live for 200 years. She didn’t make it. Wife of the celebrated Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, Kodama died late in March at age eighty-six. Borges, thirty-eight years her senior, died almost forty years before Kodama at the very same age.

He also made a significant decision regarding her future and his own before he passed.

Borges and Kodama met when she was just a youth. Though initially infrequent, her appearances in his life left an impression. As an adult, she became his secretary, personal assistant, and traveling companion—Borges was blind—and would read stories to him, sometimes in Greek, which she spoke but he didn’t.

“She would read to him, and he fell in love with her voice,” literary agent Andrew Wylie told the New York Times, “which was something that you could easily imagine him doing, because her voice was very particular and interesting and lovely.”

Their relationship was, by all accounts, platonic—though perhaps not for lack of trying on Borges’s part. “Borges pestered her to marry him throughout the 1970s, but she always refused,” writes James Halford in the Sydney Review of Books. Kodama’s parents divorced when she was just three, making, as she saw it, her own prospects fraught.

Liver cancer finally intervened in 1984. Borges declined treatment, and his health declined in response. By spring of 1986 the cancer claimed his body, though not his hopes. In March he again asked for Kodama‘s hand, and this time she agreed to a secret wedding “to make him happy.” He died two months later.

Imagine Kodama’s surprise when she discovered Borges had entrusted her with his considerable literary estate. He’d actually willed it all to her in 1979 without telling her. “If I had known,” she said, “I would have left him.” Instead, Kodama became the primary protector and promoter of Borges’s legacy.

From the time of his death to hers nearly four decades later, Kodama ensured Borges’s books were edited, translated, updated, published, and protected from copyright infringement. She signed contracts, sued, and was sued. According to Halford, who interviewed Kodama in 2016, she called the period “thirty years of hell.”

Part of the challenge, said Halford, was Borges

had left his affairs in a mess. The new widow not only had to contend with the grievances of Borges’s housekeeper, nephews, and the Argentine media, but also the unique editorial difficulties posed by a fragmented oeuvre consisting of hundreds of very short texts.

While people, including Halford, criticize some of her decisions, she rose to the occasion and seemed to relish the role. Now she’s gone, and the greatest plot twist in the Borges-Kodama saga has only just emerged: Kodama, sole protector of Borges’s legacy, left no will.

Kodama famously disliked talking about what would happen to the Borges estate after she died. “She didn’t like to talk about those issues,” her lawyer told the Associated Press. “She didn’t talk about her death.” Hence her statements, made often, about living to 200. Now a handful of nephews she disowned in life are in court claiming the treasure, and if it doesn’t go to them, it might well go to the Argentinian government.

So we have the ingredients for a great Borges short story: an author selects someone to watch over his estate; she studiously applies herself to the task, and yet appoints no one to the role after she’s gone. Halford notes that Borges is buried in Geneva, Switzerland, a few plots down from John Calvin. Appropriate since outcomes such as this cause one to reflect on the dueling roles of destiny and human choice.

¶ No paper trail. One of the criticisms leveled at Kodama was how she handled critical editions of Borges’s books. She didn’t prioritize them at all, much to the chagrin of literary scholars seeking to study his work. “It is almost impossible to trace the development of Borges’s style and ideas,” says Halford, because no available editions of his books “offer even the most minimal explanation of the chaotic, non-chronological sequencing of the collected texts.”

Interestingly, Borges himself contributed to the chaos. Dissatisfied with his earlier work, Borges rewrote much of it later in life but left no paper trail to mark the divergences. “Many of the early texts,” says Halford, “have been extensively rewritten by the older Borges who grew to dislike his youthful style but there are no notes to indicate the changes.”

I honed in this passage of Halford’s lengthy essay on Kodama and Borges because of its intersection with contemporary questions about various literary estates rewriting passages in authors’ books: first, Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming and then Agatha Christie.

While I dislike this move, I also recognize the estates’ rights in making changes and their commercial interest in doing so. Unless the author left strict instructions that their corpus remain inviolate, the estates have the legal right and possibly the financial responsibility to make changes that will preserve the commercial viability of they books they steward. It’s all a question of who owns the words.

But what if there’s no will? Who owns the words then?

Imagine this ugly thought experiment: Kodama’s nephews are unsuccessful in claiming Borges’s literary estate and it passes to the Argentinian government, a distinct possibility. Now imagine the government decides at some point to update and edit the books in keeping with its interests. Without critical editions already in existence, it might prove difficult to spot the differences, and if they’re the only editions available then it wouldn’t matter anyway. The state could essentially co-opt Borges’s enormous literary influence to reflect its own concerns.

Wherever you are in the afterlife, George Orwell, check your notifications.

If you’re enjoying this post, take a second and hit the ❤️ at the top or bottom of this post, and please share it with your friends.

¶ When authors regret their work. Borges’s distaste for his earlier work isn’t unique. If you know the Bible’s story of the flood, you know that humans rebelled after God created them. The Almighty tolerated the mess for a while but eventually, the narrator tells us, “the LORD regretted that he had made man. . . “ (Genesis 6.6).

Authors sometimes regret their work. “Arthur Conan Doyle famously hated Sherlock Holmes so much that he tried to kill the character off,” says Alice Nuttall, writing at Book Riot. “Agatha Christie resented the public demand for more Poirot novels; she found her creation irritating. . . .”

Nuttall mentions several other cases where authors came to loathe their creations. Some regretted their work for its unintended consequences; Peter Benchley was horrified Jaws motivated shark hunting, and William Powell hated that terrorists cherished and consulted The Anarchist Cookbook.

Others lamented the impact of the work on their lives; Lewis Carroll disliked the fame created by Alice’s adventures, and A. A. Milne wished Pooh hadn’t overshadowed the rest of his literary output. Still others, like Borges, dislike the quality of their earlier work; Octavia Butler called Survivor “offensive garbage,” and J. G. Ballard sometimes pretended he never wrote his first novel, The Wind from Nowhere.

¶ An older book by a younger self. What does an author do when they no longer identify with a book they wrote? If you’re Borges, you rewrite. But not everyone makes that call.

Working with Ishmael Reed in 1974, Alison Mills Newman published her first novel, Francisco. It became something of an underground classic, and copies—never very numerous—became impossible to find. When the decision was recently made to republish the book, the question arose: How much, if anything, to change?

The difficulty of the question was heightened by a dramatic alteration in Mills Newman’s life. In the decades between the book’s initial publication and subsequent reissue, she’d gone from member of the counterculture to devout Christian. She no longer identified with the language in the novel or what she chose to depict. Sophia Nguyen writes about Mills Newman’s internal struggle over how to handle the discrepancy.

Mills Newman wavered about the project and what form it might take. Maybe she could find some alternative for the f-word, swap out another expletive and just use “mess.” Eventually, she went to Florida and sat on the beach. . . . She let God talk to her, she said. She thought about Paul before he gave himself to Christ and how Peter, too, had used profanity before he was renewed. She thought of the girl she had been—and that girl’s fight to protect her life, “her wholeness,” from exploitation: “I wanted to respect her, and what it was to be 20, 21. I didn’t want to censor her.” Mills Newman said to herself: Okay.

“It was a very tender decision for me,” she said. “And I hope and pray I made the right decision to let her be.”

It’s worth reading the whole story.

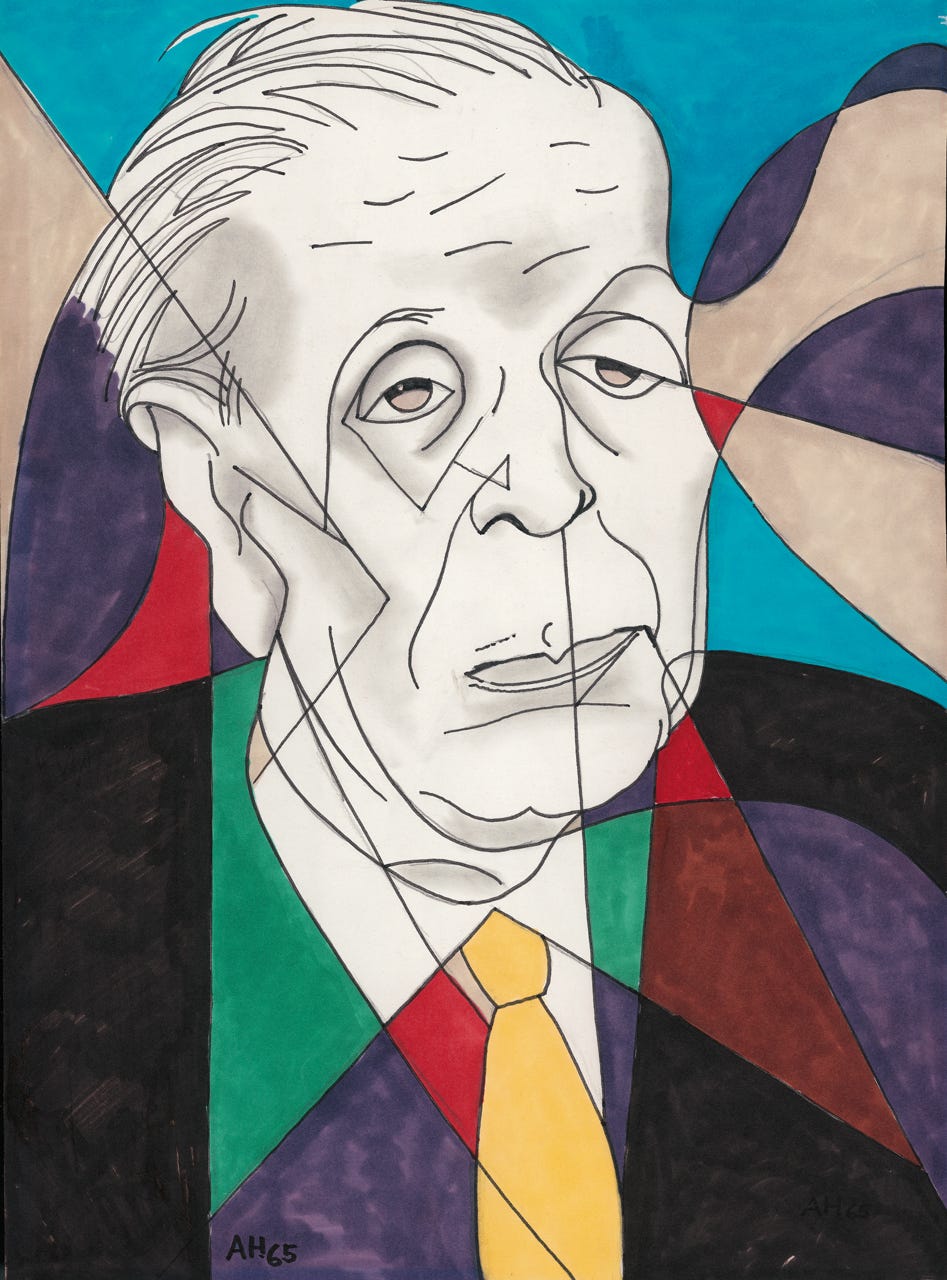

¶ Borges and Buckley. Borges appeared on Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr. in 1977. It’s a fascinating exchange between two public intellectuals. Worth a watch.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, hit the ❤️ below and please share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I remember reading Ficciones in college. Although I don’t remember the stories, I think they stretched my 18-year-old mind. I may pick this one up again. :)

Fascinating. Always wondered how things would pan out when Kodama passed. (May she rest in peace, although I didn't like that she was mean to Hurley; I liked the essayistic dimensions of his translations) As a writer, reader and Borges fan firstly, I don't object to her disregard of scholarly editions though: that only adds to the mystery, does it not? :-) As Kundera once wrote: "The Kafkologists have killed Kafka." A truth of which Borges was no doubt aware, given that he was kind of a kindred spirit of authors like Kafka.

I have to say it though: the "(shrug) it's a private company" argument when it comes to those estates is the same as surrender. It wouldn't be if there was nothing ideological whatsoever to do with these revisions. But it is completely ideological. It's a chess move where censorious believers in ideology take over unassailable terrain. This makes the situation no different from the Argentine state controlling Borges' works, except that different parties will have different needs. The ideological conquest of an estate, however, is total until a work enters the public domain. (And who's to say they won't pass laws preventing books from entering the public domain?)