The Vital Necessity of Very Old Books

Every Age Echoes with Its Own Ideas. Ancient Voices Offer a Way to Cut Through the Noise. A Response to a Critic of Old Books

For its Self-Indulgence issue in December 1973, National Lampoon dreamt up a spoof publication called Me Magazine, billed as “The ultimate special interest magazine.” Addressed to Mr. Walter J. Arnholt, the cover featured the same Mr. Arnholt, led with an editorial by Mr. Arnholt, contained letters to the editor by Mr. Arnholt, and then ran through the litany of regular magazine departments—including horoscope—all by, for, about, and featuring Mr. Arnholt.

“I’m not just a face in the crowd,” he says, “I’m an individual, with my own personal style, my own special tastes, my own unique outlook on life.” An ad pictured Mr. Arnholt reading his own magazine, his picture on the cover, creating an absurd recursion: Arnholt reading Arnholt, reading Arnholt, reading Arnholt . . .

Satire only works if it rings true. And in the 1970s, Me Magazine did more than ring true.

A Echo, Not a Choice

“The Me Decade,” as Tom Wolfe dubbed the period in 1976, devolved into a cartoon of “remaking, remodeling, elevating, and polishing one’s very self . . . and observing, studying, and doting on it. (Me!)”

The culture became obsessed with my spirituality, my desires, my reality, my truth, myself. Books such as How To Be Your Own Best Friend, Looking Out for Number One, and What You Think of Me is None of My Business topped bestseller lists. The subtitle of the last captures the promise of the period: “follow your own inner path to happiness, success, and self-fulfillment.”

But there’s a cost to following the echo. In 1977, private detective drama The Rockford Files aired an episode called “Quickie Nirvana,” which played off the self-serving spirituality of the time. In one scene Rockford and his client, Sky Aquarian, argue in a restaurant. “I’m into an alternative lifestyle,” she says. “I’m a seeker after truth.”

“All that love and freedom is just another way of saying me first!” Rockford protests. But then, after saying Sky relies too much on the opinion of others, Rockford asks, “Don’t you have any answers of your own?” So while chiding her for putting herself first, Rockford can’t help but tell Sky to put herself first.

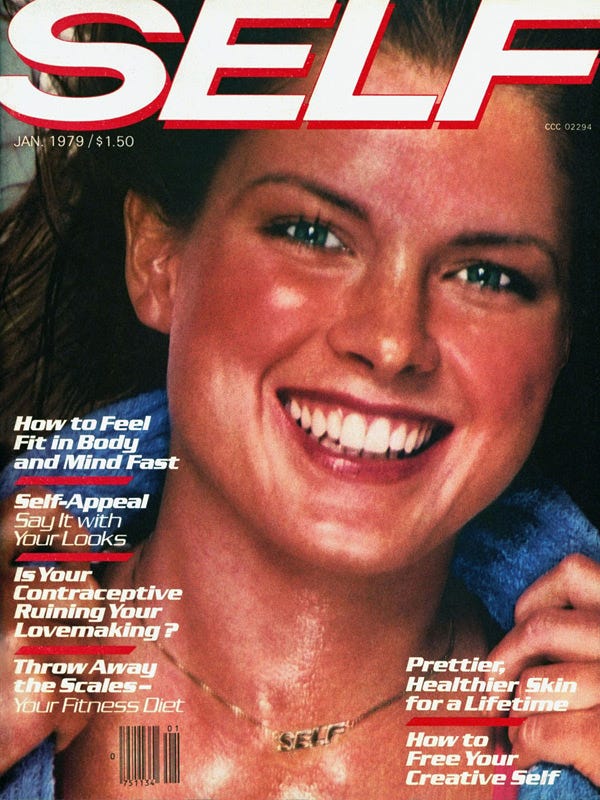

Finally, proving there’s a fine line between parody and prophecy, in 1979 Phyllis Starr Wilson founded Self magazine. The Lampoon’s editors should have sued for a royalty. But then how can you steal an idea that’s everywhere? Self just amplified the echo already bouncing off the walls of the cultural bubble.

A Case Against Books

I bring up the 1970s and its egotistic fixations to respond to a recent post by Richard Hanania: “The Case Against (Most) Books.” Hanania argues that most books are a waste of time. “One would like to think that if someone has written a 300-page book, it means that they have 300 pages worth of things to say,” says Hanania. “My experience is that is rarely the case.”

I get it. My professional background is rooted in publishing. Though in my experience the dynamic usually works the other way—authors running long, editors fighting the overgrowth—authors do indeed pad manuscripts to hit contractual word counts. I’ve seen it happen, and I’ve certainly read the effects of it, too. I’ll never forget the dictum of book and magazine publisher Al Regnery: “Most books should be magazine articles, and most magazine articles shouldn’t be written.”

There’s more to Hanania’s case, and I urge you to read the rest. He’s not wholly against books. He, for instance, recognizes three types worth our scarce time and attention, specifically: history books, books of historical interest, and books by leading thinkers that will tend to expand your own thinking.

Beyond this pale? Hanania singles out old books, the so-called greats, as particularly worthless.

A few months ago, I picked up Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. . . . I wanted to be deeply impressed by the book, because it sounds good to have a worldview with a basis in an ancient philosophy. But it’s all basic stuff like “don’t worry about what others think of you,” and “control your emotions.” Maybe it was mind-blowing the first time someone said these things, and it’s definitely sort of cool that a Roman Emperor can communicate with you across two millennia. But I’m 100% certain that if you gathered some passages from Marcus Aurelius and hired a halfway intelligent blogger to produce content made to sound like Marcus Aurelius, nobody would be able to tell the difference.

You might want to read the Stoics out of historical curiosity. I’ll claim them as part of my intellectual tribe to signal that I reject the moral underpinnings of both Christianity and wokeness, the two most powerful faiths in our society. But anything intelligent or insightful they said you’ve probably absorbed already through run-of-the-mill blogs and self-help books, shorn of all the stupid things that inevitably made their way into their writings.

If you haven’t already hit the eject button on this flight, allow me complicate matters somewhat—using the example of self-help books to which Hanania has appealed.

Adding to the Echo

There’s no need reading Aurelius or the other Stoics, says Hanania, because “anything intelligent or insightful they said you’ve probably absorbed already through run-of-the-mill blogs and self-help books, shorn of all the stupid things that inevitably made their way into their writings.”

It’s true that there are intelligent and insightful Stoic ideas in self-help books and blogs; two and a half feet to my right currently stands a copy of Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way. It’s a distillation of Stoic thought, and I’m told by many it’s great (I haven’t read it yet). But it’s false to think that we’ve so absorbed Aurelius and the Stoics that we can simply settle for contemporary restatements and get on with things.

It is true that we’ve absorbed a lot of their ideas, but we’ve absorbed a lot else besides, most of it unknowingly. Every period has its own blind biases and hidden inclinations—whatever echoes off the bubble. The egotism of the 1970s provides a useful example. When I worked at a used bookstore in Roseville, California, just out of high school, I shelved tattered copies of all those ’70s self-help books. There was a sameness to most of them. Their packaging and contents all fell within certain marketable parameters for the period. To their original readers, every volume probably felt fresh and unique. In retrospect, they’re various shades of the same color.

We’d be naive to think we don’t have our own version of the homogenization problem—one humorously close to the 1970s, actually. We’re every bit as individualistic as we were then and actually more so, as various strong-ties have lost social power and people can self-serve and self-define reality online.

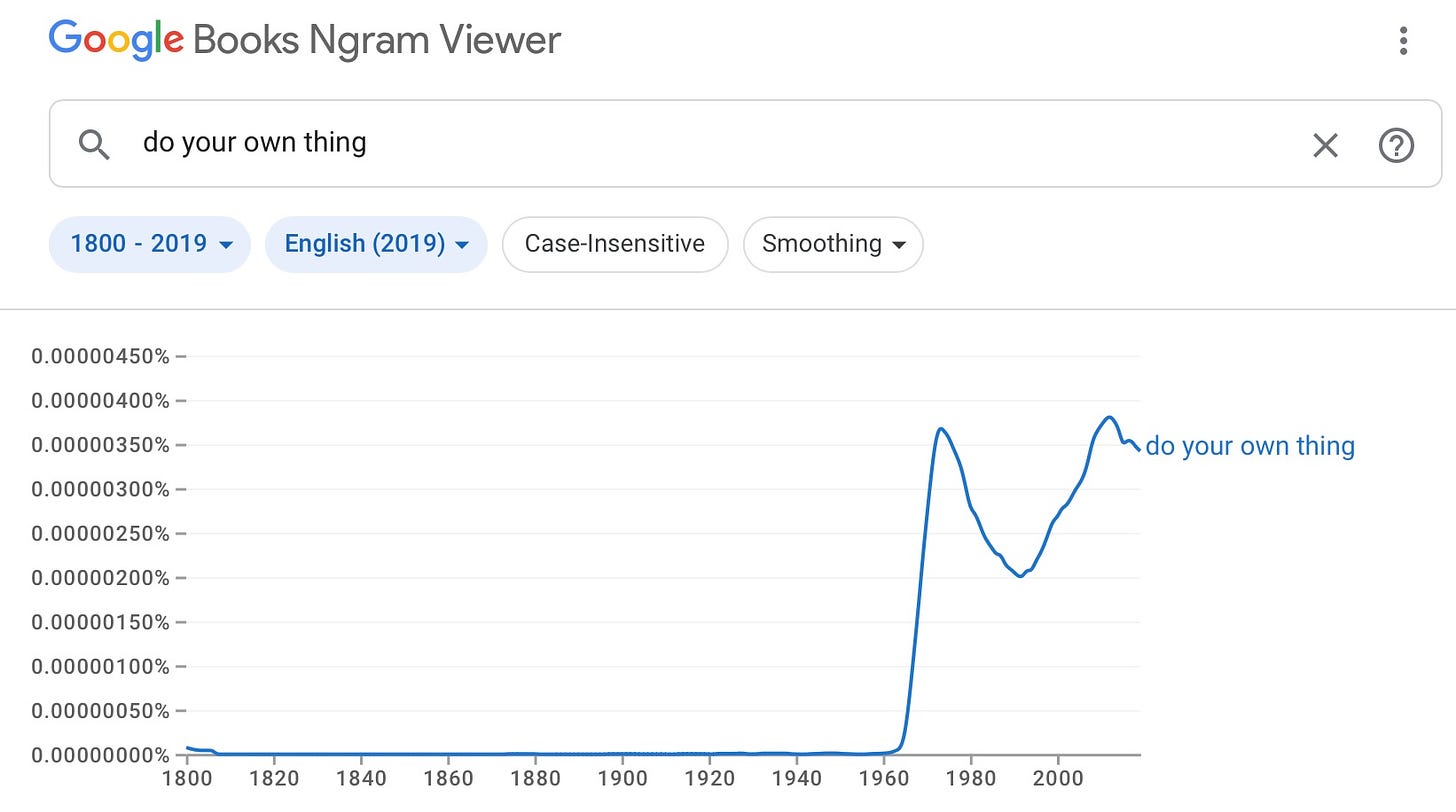

We’re all radical individualists by preference and manner even if we wouldn’t claim the title. You can sometimes see this in our language. Take the ‘70s catchphrase, “do you own thing.” It’s popular again.

If we’re reliant on modern restatements of Marcus Aurelius—or any other ancient thinker—we’re not actually getting Marcus Aurelius. We’re getting whatever bits of his thinking tend to echo in our current bubble. Some of it might be very good and beneficial. But it’s limited by the biases and assumptions of our times, most of which we’re unaware of. We need different voices to cut through the echo.

Going Wrong in Different Directions

Hanania says we should be wary of old books because the writers got stuff wrong back then. “It’s not simply that the ancients had less information and access to empirical data,” he says, “but ways of thinking have improved over time. . . . We take the basics of the scientific method for granted today, but only after generations of newer scholars throwing off the shackles of official dogma.”

I’m quick to agree there have been advancements, and I’m happy to live in a world that benefits from those advancements. I have no arguments with the scientific method, the theory of relativity, microchips, nuclear power, medicine, whatever. I’m a big fan.

I’m also quick to insist ancient, medieval, and early modern writers sometimes captured thoughts and emotions inaccessible to us precisely because they speak across a cultural divide. We don’t share their priors and so conceive of the world somewhat—or even radically—differently. Old books offer cognitive and perspectival diversity.

Marcus Aurelius appeals to modern readers because they find some of his worldview in theirs. But the value in his writing is that he lived outside our time. He was not a modern individualist, despite aspects of his thought that might resonate as such. That’s a feature, not a bug. It’s the same with other ancient writers. Augustine’s Confessions is utterly self-absorbed, but it’s not egotistical. Their benefits lie in both their similarities to us and their difference from us.

Hanania’s right: Authors of the past believed erroneous stuff. But we commit an error of our own in assuming we don’t. And there stands a primary benefit of old books. Ancient authors were prone to different errors than our own and, as C. S. Lewis said, they’re also unlikely to affirm us in ours. Reading old books is a form of crowdsourcing. “Two heads are better than one,” he said, “not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction.”

Thinking New by Thinking Old

Responding to Hanania,Henry Oliver pushed this line of thought even further.

[Hanania] is confident that ways of thinking have improved over time. I agree—we had the Enlightenment!—but there’s more variation in this than you might expect. . . . The true genius is the person who keeps finding new ideas and is able to think for themselves rather than learning the same things as everyone else and ending up with the same badly thought-out opinions. The more you read only new work, the less chance you give yourself to discover new ideas. . . .

Instructively, Oliver got that idea from reading John Stuart Mill, who (let it be noted) has been dead for quite a while now. But the point, says Oliver, isn’t the conclusion—true as it might be. “You don’t just read old books for content: you read them for method.”

Sticking with self-help for a moment longer, if the conclusions were all we were after you could just skip reading all those books entirely. Chris Taylor at Mashable distilled most of their messages down to just eleven takeways, stuff such as: “take one small step,” “change your mental maps,” “instant judgment is bad,” and “remember the end of your life.” It all sounds pretty banal stated like that, and maybe some of it is. But the point of reading isn’t simply conclusions or bare content. It’s thinking through ideas for yourself.

The process of thinking is what produces most of the value of reading. Engaging with ideas, not simply registering them, is what helps. Older writers make moves that modern writers do not. They handle arguments differently, stress different emphases, focus on different facts.

That cognitive and conceptual diversity opens up new possibilities and provides the raw material for novel thoughts unavailable to people thinking within the contemporary bubble. It’s the central dynamic of the innovative process, mixing common and disparate elements. It’s also one key reason humanities have a future in the modern university, grounding and enriching STEM disciplines.

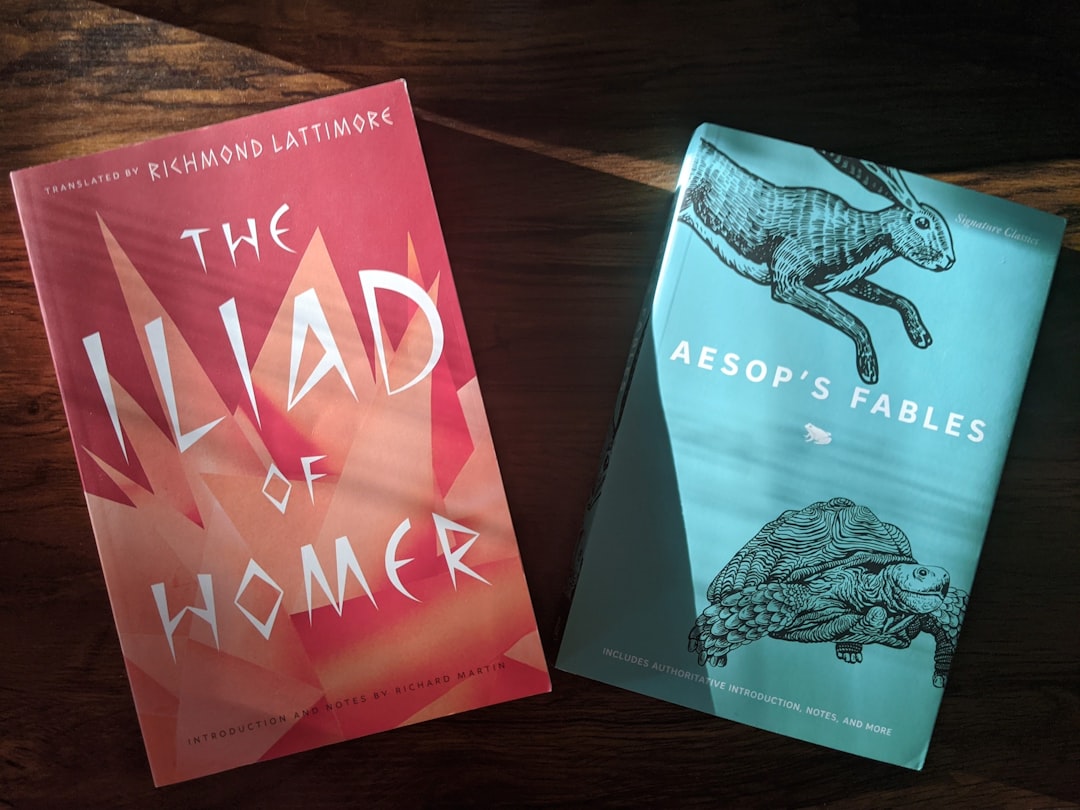

Based on Hanania’s own criteria for books worth reading—history books, books of historical interest, and books that tend to expand our thinking—old books would seem to warrant attention. They’re witnesses to history, the original sources. And they can open new pathways for thinking today.

Without old books, we’re just Arnholt reading Arnholt, reading Arnholt, reading Arnholt . . .

Our Common Plight

Finally, it’s worth saying that some of those old books speak to us precisely because our lives bear so much commonality with that of our predecessors.

“The ‘Iliad,’” said G. K. Chesterton, “is only great because all life is a battle, the ‘Odyssey’ because all life is a journey, the Book of Job because all life is a riddle.” For what it’s worth, he said that over a hundred years ago.

Whether for discovering useful ways of thinking, accessing conceptual and cognitive diversity, or simply seeking human solidarity amid the trials of life, reading old books is a winning strategy.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I also think there is something very reassuring about realising that people many years ago were grappling with many of the issues we do

Joel, there's a good article in the current Harpers by Tom Bissell that captures Stoics and their subsequent (mis)interpretations by modern self-help artists. But also a piece that shows the ways that Bissell used Stoicism to work through the death of his father -- in a way that probably old Marcus would feel was true. "Time is a Violent Stream," May 2023.

Thanks for this article.