Books Divide Us, but They Can Also Heal

Differences Are Inevitable—But Censorship Is Not the Only Response

“You can’t exist as a writer for very long without learning,” said Margaret Atwood, “that something you write is going to upset someone, sometime, somewhere.” The same goes for readers: You can’t exist as reader for very long without learning some book, sometime, somewhere will upset you. Welcome to literature. Now what?

Two recent reports by the free-speech literary organization PEN America reveal how many respond. Let’s dip into both.

Witch Hunt

When Laurie Forest wrote her 2017 YA fantasy, The Black Witch, she imagined she could constructively address racism through the story of someone who repudiates it. In the world of the novel, people are raised to disdain Fae, Kelts, Selkies, Lupines, and other races. But when Forest’s heroine, a young woman named Elloren, heads off to university to become—what else?—an apothecary, her views flip 180 degrees.

Forest’s story is, as the loaded term goes, woke. But apparently not woke enough. An online storm began raging before the book even released when a reviewer called it “the most dangerous, offensive book I have ever read.” Maybe she was sheltered.

To make her case the reviewer daisy-chained racist quotes from racist characters in a 9,000-word(!) critique. “What her review failed to contextualize,” said PEN America in Booklash: Literary Freedom, Online Outrage, and the Language of Harm, “was that these quotes from the book’s racist characters provide the starting point for the protagonist’s narrative arc.” To tell the story of a character’s reversal, the author must first depict what the character is abandoning; otherwise, there’s no story. And as any novelist knows, you don’t tell, you show. But, please, don’t confuse me with the details!

As the mob coalesced and descended, The Black Witch was review-bombed on Goodreads, and thousands piled on at whatever social media venue they could access to demand the book be pulled in advance of publication. That’s worth stressing: The storm occurred before all but a few could have even read the book; denunciations were fueled by the book’s presumed contents. One reviewer’s subjective—and untenable—reading became the only viewpoint countless others required to let gravity do its thing with the guillotine blade.

The New Normal

If you’re new to the drama surrounding Forest’s novel, as I was, it would be easy to view it as an aberration. But, no. Sadly, it’s just one of many instances of an emerging trend documented by PEN Booklash. High-profile targets include J.K. Rowling, Elizabeth Gilbert, and Jeanine Cummins, who was hounded from public life for her novel American Dirt. But the carnage spreads far and wide.

While, to its credit the publishing industry is addressing underrepresentation of minority voices both in its staff and its products, a new breed of puritan has arisen in online communities to accelerate changes and harass anyone who differs, lags, or simply fails to read the chatroom in ways they approve.

“In the past several years,” says Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and PEN America president Ayad Akhtar in the introduction to Booklash,

books deemed problematic due to their authorship, their content, or both have been subjected to boycotts, calls for withdrawals, and harassment of their authors. Some have argued that merely to read the book is to become complicit in its alleged harms. While proponents of these arguments are, of course, free to make them, such arguments risk laying the groundwork for, and justifying, the ostracism of authors and ideas and the narrowing of literary freedom writ large.

What are these supposed harms? One includes writing from a perspective other than the author’s own (as if an author’s imagination can be regulated, even dictated from the outside). Another is, as in Forest’s case, representing characters with racist, homophobic, and other undesirable attitudes (as if depiction were the same as advocacy).

“Novelists should feel free to write from whichever viewpoint they wish or represent all kinds of views,” says Nobel Prize-winning novelist Kazuo Ishiguro against the new, ascendant view. Ishiguro has written from the perspective of all sorts of people, including an android in the beautiful Klara and the Sun, and has imagined aspects of every sort of social wrong. Seems to work for him. What gives?

“I think I’m in a privileged and relatively protected position because I’m a very established author,” he says. It’s new authors he’s worried about—people like Forest, people still trying to build a reputation, whose only asset might be an unconstrained imagination and the willingness to try out fresh ideas.

“I very much fear for the younger generation of writers,” says Ishiguro. One misstep and an “anonymous lynch mob will turn up online and make their lives a misery.” As a result, authors say less to risk less. And we, as readers, are all poorer for it.

Booklash details several instances of what can happen when authors stray from approved stories, characters, and approaches. In some cases, if the mob is loud enough authors feel compelled to edit their books and alter their original vision. In other cases, publishers actually pull the project and cancel the contract. And as if all that weren’t bad enough, this rise in progressive censoriousness comes as another sort of censoriousness is also on the rise.

Why Johnny Can’t Read That

While the phenomenon of online purity policing comes from the left, the battle in schools has been largely waged by the right. And the battle, according to the second of PEN’s two recent reports, Banned in the USA: The Mounting Pressure to Censor, appears to be heating up.

I stress appears because the numbers aren’t so cut and dried. “During the 2022–23 school year,” said the report, “PEN America tracked 3,362 instances of book bans, an increase of 33 percent from the 2021–22 school year.” In the prior year, PEN noted 2532 instances. But

of Prufrock raises some issues with these numbers.“Of those supposed 3,362 instances of censorship,” he says, “we find that only 1,886 were actual instances of censorship. The other 1,476 were books banned ‘pending an investigation.’” Which is to say, some—maybe even all—in that pile could end up back on the shelves, reversing the trend. What’s more, he says,

1,313 of the supposed 3,362 instances of censorship originated with the schools’ administration, not the parents. Furthermore, PEN reports that nearly 600 of the challenges were “informal,” which means what? A librarian remembers someone asking a book to be removed or overhears someone complaining about a book?

It’s worth noting the content of these contested books. Many concern sexuality deemed age-inappropriate by those advocating the ban, including parents. As the parent of five children, four of whom have attended both public and private schools for parts of their education, I’m sensitive to this issue and appreciate where parents are coming from.

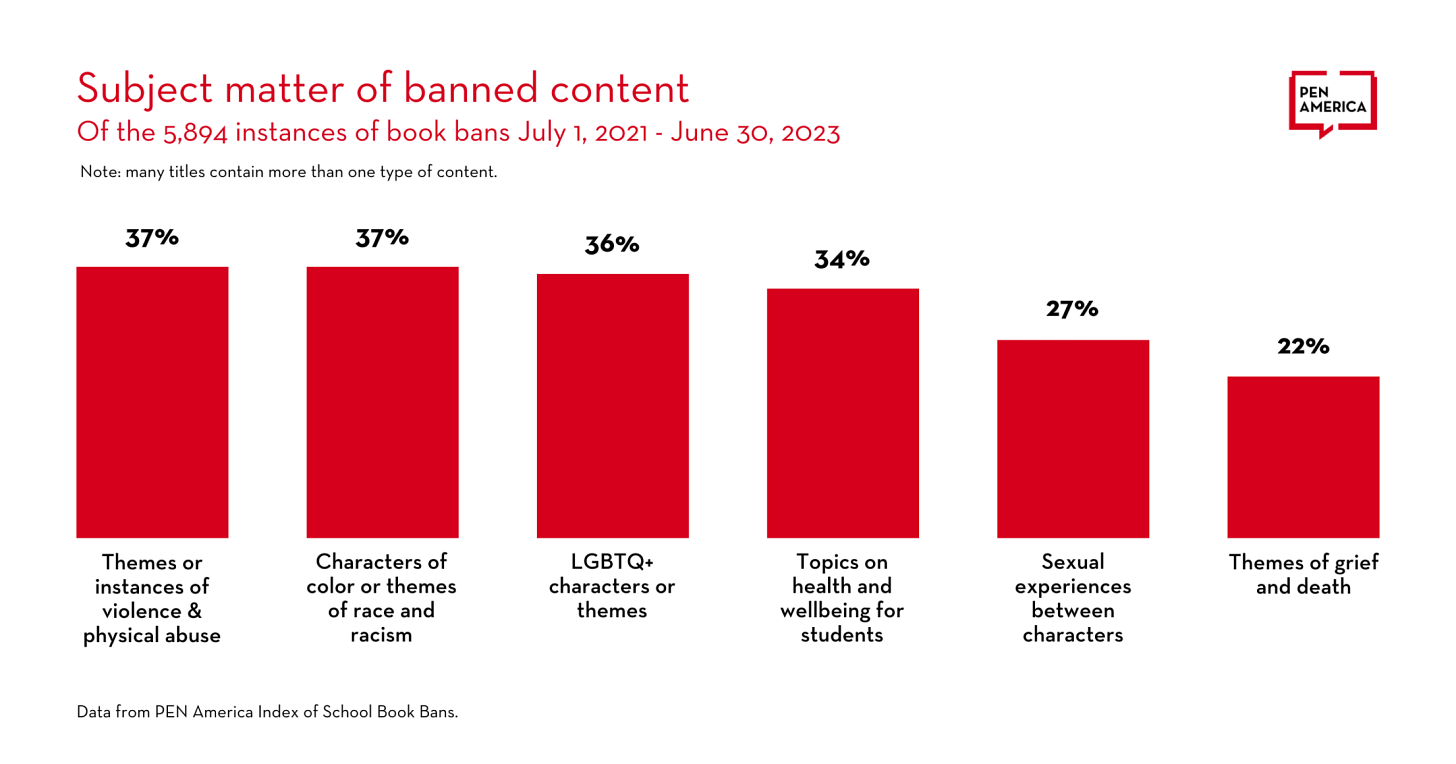

But sexually questionable content isn’t the only reason for the bans. A large number of books have been targeted because they concern race and racism. In the 2022–23 school year that number was 30 percent, according to PEN. If you expand the view to July 1, 2021–June 30, 2023, the number jumps to 37 percent. My interpretation: The higher number reflects the overreaction of uneasy parents to the so-called racial reckoning in 2020. I have much less patience with this; three of my five kids are black, and the idea that books are pulled because they address racial injustice sits poorly with me—to say the least.

Nor are these issues the only ones for which books are banned.

Contested curricular and extracurricular reading are not an argument for banning books; if anything, they present a rationale for school choice. Barring that, we can expect more theatrics around book banning regardless of the actual case on the ground. The reason? Books have become a new front in the culture war.

‘I’ll Burn Those … on the Front Lawn of the Governor’s Mansion’

According to Banned in the USA, “PEN America’s ongoing research and analysis point to two influential drivers behind [banning efforts]: advocacy groups and, increasingly, state legislation.” Though two thirds of Americans oppose book bans, efforts to pull books have been gaining traction and—worst of all—garnering media attention, which just feeds the beast.

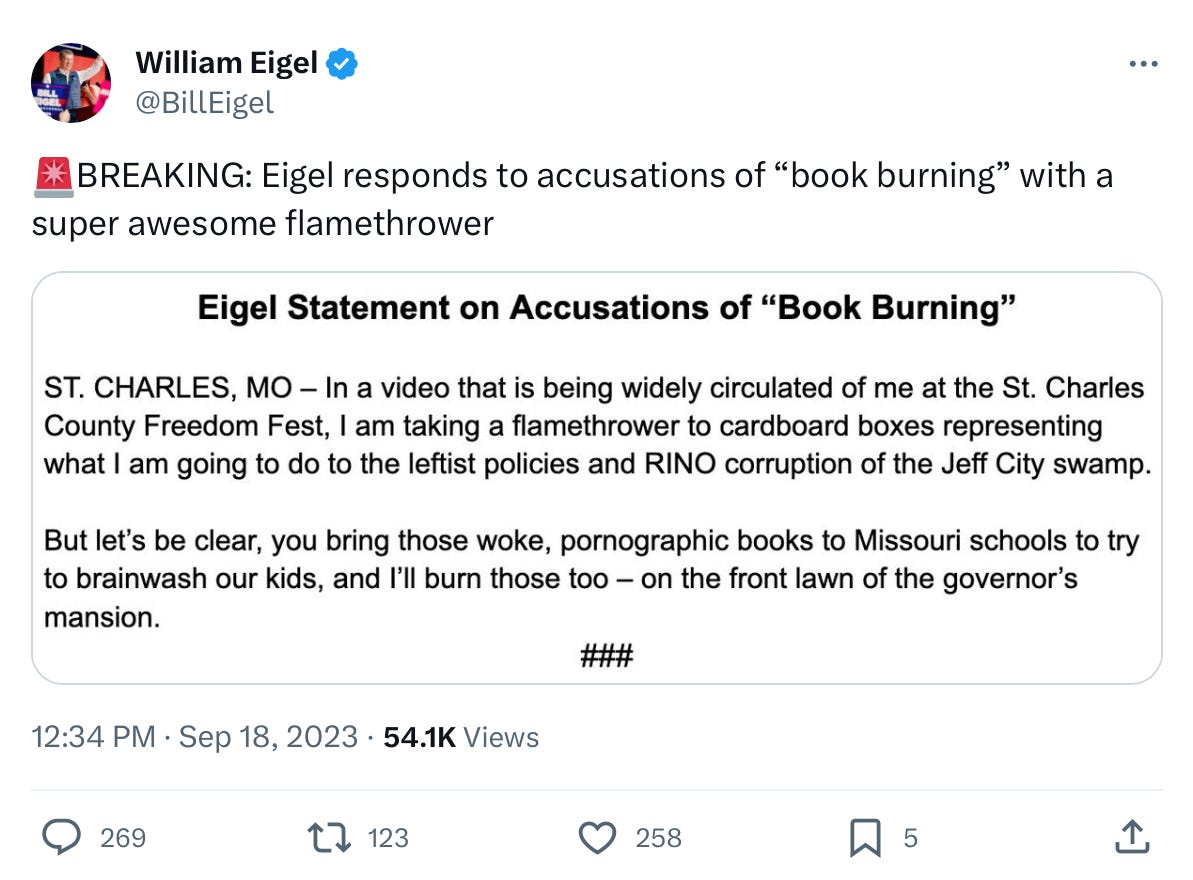

When Missouri Republican state Sens. Nick Schroer and William Eigel used a pair of flamethrowers at an event, the video went viral as people—including me—assumed they were burning books. They weren’t. They were burning a pile of empty boxes, according to video’s original poster and an analysis by the Associated Press. But Eigel, who is also running for governor, was quick to take the bait and play it up for his base.

“Let’s be clear,” said Eigel, “you bring those woke, pornographic books to Missouri schools to try to brainwash our kids, and I’ll burn those too—on the front lawn of the governor’s mansion.”

I hardly care what’s between the covers: An American politician proudly announcing he’ll burn books qualifies as disconcerting, and the idea that such rhetoric works for his presumed audience is, frankly, even more disconcerting.

It is normal, even healthy, that Americans are polarized. After all, none of us has to think the same as another. The fact we possess the freedom to differ and disagree is good. The problem is that we increasingly politicize our differences—something Jerzy Kosinski flagged back in 1969, while accepting the National Book Award:

Americans are no longer the same. . . . They wrest freedom from each other. They clearly delineate their places in society. They are angry, violent and abusive. They have become political. And the system responds in turn and invades their freedom.

Kosinski represents a mid-twentieth century consensus that viewed free speech and especially the printed page as one of our highest values. That consensus has been shattered in the twenty-first century by both progressives and conservatives. As Reason editor

recently said in a Miller’s Book Review Q&A:The Bill of Rights obviously starts with the First Amendment, but it really wasn’t until the late 1950s and 1960s that we enjoyed something approaching free expression, where you didn’t have to worry about getting arrested for publishing the wrong book or photos. I was born in 1963 and grew up in the seventies and eighties and simply took for granted that the free speech consensus of that era was the way things always were and always will be.

It became easier still in the 1990s for us to produce and consume culture and expression on whatever terms we wanted. But for the entire twenty-first century, that has been under attack in the name of state security, of decency, of antiracism/sexism/homophobia, of antitrust, policing medical or electoral “disinformation,” you name it. These days even the ACLU doesn’t take free speech as its highest value.

Books are just a battle ground as we “wrest freedom from each other.” But does it have to be like this?

The Answer, Not the Problem

These days we’re so attuned to how books divide, we forget how they can bring us together. The humanities shed light on realities we all must face to one degree or another.

Novels dealing with difficult subject matter represent one way of wrestling with these issues. It’s why high-school reading lists have featured challenging books such as Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Is there objectionable material in these books? Yes. Should teenagers read them? Also, yes. It’s how they come face to face with the issues that shape human society and their roles in it.

“Book bans inhibit a core function of public education,” says David French, writing in Reason magazine. “They teach students that they should be protected from offensive ideas rather than how to engage and grapple with concepts they may not like.” In making his case, French points to “a quirky and mostly forgotten Supreme Court case that is suddenly relevant once again.”

What makes Island Trees School District v. Pico both quirky and relevant? In this case students actually sued their school district for pulling books. They argued that denying them access to information undermined their First Amendment rights. The court agreed and did so in part part because the ban would impair their development as citizens.

“Just as access to ideas makes it possible for citizens generally to exercise their rights of free speech and press in a meaningful manner,” ruled the court, “such access prepares students for active and effective participation in the pluralistic, often contentious society in which they will soon be adult members.” In other words, if students can’t handle uncomfortable content, there’s no way they can handle the rough-and-tumble of democracy and civil engagement.

I can’t disagree, and the racially-driven bans provide perfect test case. How are we going to navigate difficult local and national conversations about racially charged policy when sheltering people from the subject? Harper Lee’s Pulitzer-winning 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird provides a manageable, if challenging, entry point for conversation, and yet schools regularly ban the book because it makes students uncomfortable. Welcome to life. It’s got sharp edges.

What’s the real message here? Book banners on the right and left are looking at books like they’re the problem. They actually present the solution.

Books Can Heal

“What the humanities can do,” Gillespie said in his Q&A, “is orient you toward the bigger picture and begin to give you a sense of how our predecessors thought about the existential questions we all need to confront.” This doesn’t mean we’ll all agree on the answers, but shared reading provides us with common stories and language to discuss our differences. We can circle around the book, instead of glaring across a political divide.

Alice Walker’s The Color Purple can, for instance, help us wrestle with the ethics of revenge and forgiveness, not by providing a treatise on the subject but by inviting us into the imagined life of someone dealing with the question and the very real impulses behind it.

One peculiar benefit of reading old books, the so-called Great Books, is the sheer distance from present controversies. When we read an older book, we can temporarily ignore whatever “side” we claim in the present and look at story for itself, as ourselves. Homer, Shakespeare, and Jane Austen don’t have a stake in our modern fights, but when we engage their work, we discover they address our concerns because as another old author said, “There’s nothing new under the sun.”

This doesn’t rule out new literature. Any thoughtfully written book can help us navigate our fraught existence. When Kirkus gave an enthusiastic review to The Black Witch, the mob descended upon the venerable publication, demanding a retraction. Kirkus declined. Instead, one of its editors, Vicky Smith, wrote to clarify the publication’s review and its position. Her words apply far beyond one contested book:

The simple fact that a book contains repugnant ideas is not in itself, in my opinion, a reason to condemn it. How are we as a society to come to grips with our own repugnance if we do not confront it? Literature has a long history as a place to confront our ugliness, and its role in provoking both thought and change in thought is a critical one.

If books help us acclimate to democratic engagement and deal with the existential realities we face, then we should spend less time worried about banning books and, as Erik Rostad recently noted, spend more time encouraging people to read, period: “High school students aren't reading books, banned or not. What if we focus there first?” After all, books can only work their magic if we open them.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I had a lot typed here, but realized that I don’t know anything, so I deleted it. Twice. Learning about ideas and viewpoints is good. Needless exposure to explicit material is not.

Yep. Very sad. We’ve seen the progressive left shift over the past decade from believing in democracy to becoming arbiters of censorship. It’s amazing how much tap-dancing people on the New Left will do to rationalize creating an illiberal, censorious environment. This latest iteration of banning startled culturally on the left circa 2013. Very few lefties said a word about cancellations, de-platforming authors, books being pulled, etc. Then far-right extremists start doing it legally (also bad) and suddenly the left is outraged. I don’t care what side it comes from: it’s anti-American. Art has always been offensive and transgressive. Writers don’t write to be safe; we write to explode society’s assumptions. People are *supposed* to get “triggered.” (By the way I really loathe New Age Millennial Woke language like “problematic” and “trigger.” Can’t people see how this makes a whole generation sound like toddlers?)

Hypocrisy.

Here’s my piece on book banning on both sides.

https://michaelmohr.substack.com/p/book-banning-happens-on-both-sides