Catch-22: ‘They’re All Trying to Kill Me’

If You Know You’re Crazy, You Must Be Sane. Reviewing Joseph Heller’s Classic Satire

What’s the best place to start a story? Joseph Heller decided to drop his Catch-22 readers roughly in the middle. The action transpires over the course of one year, 1944, as the Allies press into Europe toward the end of World War II.

Heller grounds most of his story on an American airbase on Pianosa, an island off the coast of Tuscany. And grounds is both the right and wrong verb to describe the action: wrong because the story concerns a squadron of US Army Air Force bombers actively flying endless missions over Italy to subdue the country; right because the protagonist, bombardier Yossarian, refuses to fly any more.

It’s a quiet protest. Yossarian wants to go home. He’s flown the required number of missions for a ticket back. But Colonel Cathcart, intent on boosting his image and gaining promotion by any means necessary, keeps hiking the number. Just when Yossarian and his fellow airmen get close to the quota, Cathcart jacks it higher.

Twenty-five missions are required at first. Then Cathcart bumps it to thirty, then thirty-five, then forty. By the time Yossarian enters the hospital with a fake liver complaint, it’s up to fifty. And he doesn’t want to fly again. Yossarian takes the war personally. “They’re all trying to kill me,” he says early on.

Yossarian’s no coward, however. In one instance, he overflies a target and fails to drop his bombs; so he doubles back and drops his bombs in the face of increased enemy antiaircraft fire. No, Yossarian simply finds the whole enterprise pointless and dehumanizing and Cathcart’s escalating mission count unjust.

The rising count drives the plot. It’s one the few ways to keep the storyline straight because Heller eschews a chronological narrative. Instead, like Yossarian with his bombs, Heller repeatedly doubles back through 1944, deepening the madcap plot and developing his oddball characters in absurdist vignettes that push and pull the action forward from the late summer of 1944, when Yossarian’s liver doesn’t act up but he pretends like it does, until the climax of the action at the end of the year.

You only know where you are in the story because—there he goes again—Cathcart bumps the requirement up to sixty, then seventy, then. . . .

The narrative effect is disorienting—maybe even crazy-making—which is appropriate because Heller’s satire exposes the insanity of war and what it asks of the people tasked with fighting it. If the airmen don’t understand what’s happening to them, Heller feels no obligation to enlighten the reader; we suffer while they do.

We also laugh.

Clowns in Uniform

Catch-22 is a vulgar, hilarious, and maddening clown car of a book—every chapter a door out of which new buffoons tumble to shock and entertain. While Yossarian is in the hospital, for instance, we meet Chaplain Tappman, an insecure Anabaptist who endures miserable treatment from both his superiors and his one direct report, an atheist corporal.

As an example of his many travails, Colonel Cathcart asks Tappman to compose a prayer before missions but says it can’t mention anything “too negative. . . . Haven’t you got anything humorous that stays away from . . . God? I’d like to to keep away from the subject of religion altogether if we can.”

The two finally settle on a prayer for a tighter bomb pattern. But then Cathcart wants to include only officers in the prayer, and the chaplain protests. He says that God might not grant the prayer if the enlisted men are excluded. “The hell with it, then,” says Cathcart. “I’m not going to set these damned prayer meetings up just to make things worse than they are.”

Then there’s Doc Deneeka, a self-absorbed whiner who might help Yossarian if he weren’t too busy covering his own flank. It’s Deneeka who first explains Catch-22: A flyer can be grounded if he’s insane, but he’d have to petition to be grounded which, in light of the fact that flying over enemy territory is dangerous, would indicate rationality. “Anyone who wants to get out of combat duty,” he explains, “isn’t really crazy.” If you qualify, in other words, you’re disqualified.

Since the book’s publication “catch-22” has taken on wider cultural meaning of any situation in which a person is trapped in self-defeating logic. As the title suggests, it’s the theme behind the entire novel.

Lieutenant Scheisskopf, for instance, finds himself promoted to general above Cathcart—and pretty much everyone else. Because of hard-won skill or natural command? No. Scheisskopf is “an R.O.T.C. graduate who was rather glad that war had broken out, since it gave him an opportunity to wear an officer’s uniform every day and say ‘Men’ in a clipped, military voice. . . .” All he really cares about is winning parade competitions, for which stays up all night reading books about marching, devising plans, and conducting secret drills, while ignoring his wife.

Meanwhile, General Peckem, stuck in Special Services has been agitating for more command. Special Services has no direct combat responsibilities, but he fires off memos requesting that be changed. Scheisskopf, now a colonel, reports to Peckem and is only allowed to send out cancelations for parades that were never scheduled.

Finally, an opportunity opens up for Peckem to take another general’s spot over combat operations, leaving a hole at the top of Special Services. Scheisskopf gets promoted to lieutenant general to fill the role—at the same time the military finally concedes to all of Peckem’s old memos and places Special Services over combat operations. Now Peckem and everyone else reports to Scheisskopf. It’s a disaster. “He wants everybody to march!”

Milo Minderbinder probably wins the competition for most outrageous character in the novel. A lowly mess officer, he uses his position to construct an international black-market syndicate, buying and selling across the Mediterranean and beyond.

The math never makes sense. Minderbinder buys high and sells low but always seems to come out on top regardless, even securing local political offices because of the prosperity he somehow magically spreads through the region. He even welcomes the Germans into the business with him and excuses everything—including once bombing his own base—because “everybody has a share” of the syndicate’s profits, even though no one ever gets a share of anything. It all falls apart when Minderbinder corners the market on Egyptian cotton right when demand craters; his last brilliant idea is covering cotton balls with chocolate and feeding them to the men.

There are so many more: Hungry Joe, Clevinger, Kid Sampson, Major Major Major Major, Aarfy, Chief White Halfoat, ex-P.F.C. Wintergreen, General Dreedle. . . . In Heller’s world, the clowns all wear uniforms, except Yossarian himself—and that’s only because he finally abandons his uniform altogether, goes on parade, and even receives a medal in the buff.

Demonstrating you’re too crazy to fly isn’t easy when everyone around you is barking mad.

Right Message, Right Moment—Maybe Still

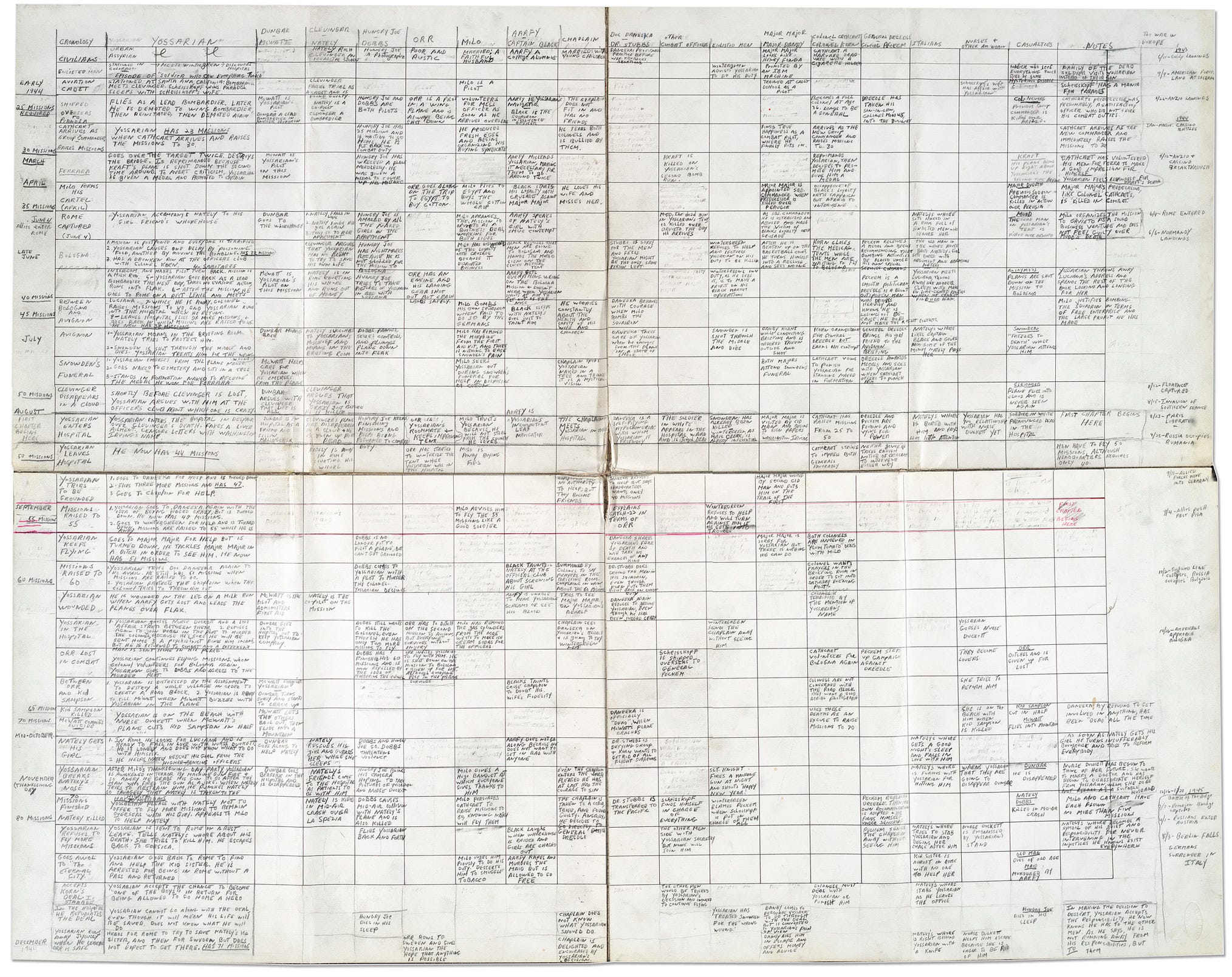

Insane as it is, Heller’s story relies his own experiences in the U.S. Army Air Force, stationed on Corsica. He flew sixty missions in a B25 Mitchell—the same plane that Yossarian flies, right up until he refuses to. The unconventional narrative structure required Heller to work off a massive hand-drawn spreadsheet to keep straight all the characters and plot points. Across the top he wrote the names of his characters and a few other moving parts; down the side he lists the dates and the mission escalations—the few fixed points in the story.

Heller started writing the novel in the early 1950s and published the first chapter in a literary magazine in 1955. Famed editor Robert Gottlieb finally purchased the book for Simon & Schuster for a total of $1,500. It went on after after a spate of hit-or-miss reviews to capture the market’s imagination and sell millions and millions of copies. “Now I get more,” said Heller twenty-five years after the book’s initial publication. What explains its success?

While absurdist social critique and satire might ubiquitous today, there was nothing quite so outlandish or outrageous as Catch-22 in print when it released in 1961, nothing so simultaneously comical and cynical.

And that year matters, too. It was just a few years before a small conflict in Vietnam spiraled out of control, drawing the U.S. into a war that became a slow-moving operational definition for the word quagmire. Heller somehow anticipated it and gave American readers an interpretive framework to describe what they watched on the news and read in the papers, as the conventional expectations for American military engagement were turned inside out and upside down.

Writing about the book in the New York Times, University of Michigan English professor John Aldridge referred to the book as “a work of consummate zaniness populated by squadrons of madly eccentric, cartoonographic characters” but which was “deadly in earnest . . . savagely bleak and ugly.”

Catch-22 is a secular theodicy, a new Book of Job played out in WWII Italy, in which God and the devil are the rules of war and the private ambitions of its participants. Injustice is the natural state of affairs. We are, for instance, only mildly shocked when Aarfy rapes and kills a maid, but, when the MPs show up, Yossarian finds himself arrested for the insignificant crime of being AWOL.

It’s a critique of the dehumanizing power of power itself—how those who wield it use others for their ends and ruin lives in the process, and ultimately how that power becomes self-defeating. It turns out Yossarian is right. They are all trying to kill him, and not just the enemy.

I can’t say Catch-22 is for everyone; I can’t even say it’s for me. But then again, if you’re looking for a way to understand the “squadrons of madly eccentric, cartoonographic characters” marching across the field of American politics today, it might shine some welcome light on the parade.

Thanks for reading! If you benefitted from this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 is the fourth book in my 2023 classic novel goal. If you want to read more about that project, you can find that here and here. So far, I’ve reviewed:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (January)

Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (February)

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (March).

In May, I’ll be reading and reviewing Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

A very good description of Catch-22 and an excellent explanation of how and why it works. I read this book in my early twenties and it blew me away. I recently re-watched the movie M*A*S*H and was reminded of Catch-22. Both try to convey the insanity of war through humour. It seems like if you made something so scathingly anti-military today it might not go well for you.

Have you ever done an entry devoted to satire writings of Christians?