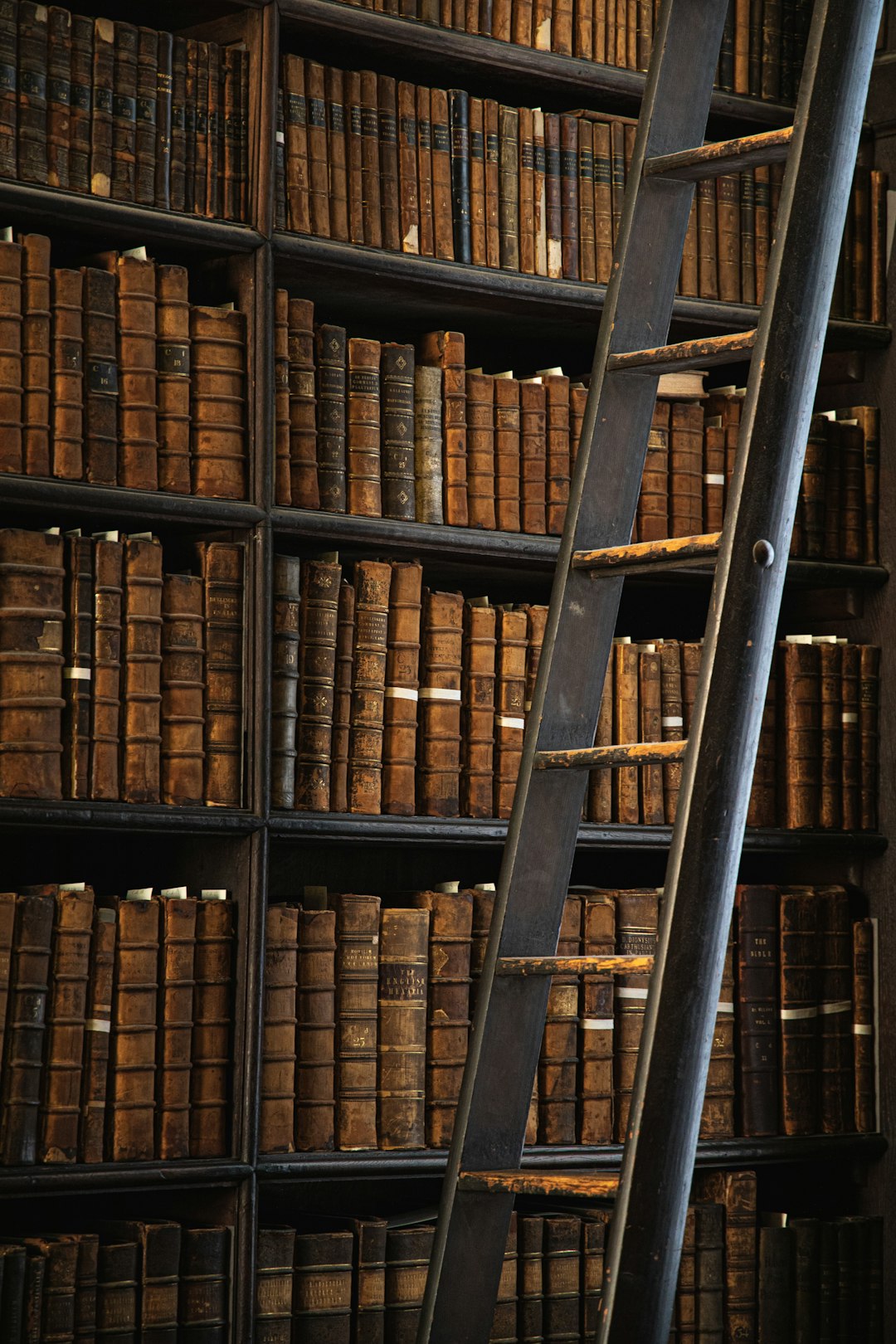

Why Read Old Books?

An Update on My Big-Ass Classic Novel Challenge for 2026

Looking over my reading a few years ago, I noticed a large percentage of newer books, titles published within the past couple of years. Nothing wrong with this. In fact, Washington Post book critic Michael Dirda cites Jean-Paul Sartre’s What Is Literature? to argue that writers—and readers—ought to be concerned with what’s happening now.

But it’s ironic to mention a book published in 1947 when arguing we should focus on the present, no? Dirda is having some fun.

While noting the value of modern books, Dirda recommends adding old books to the mix. He offers several reasons. “The foundations of learning . . . were nearly all located in the past,” he writes of his own education. “Time had done its winnowing, and what remained were the works and ideas that shaped human civilization.” These old books exert creative power, forming strands of the ideational DNA used by modern authors to spin new yarns. “In the arts, especially,” he says, “education consists of seeing how deeply the past informs the present.”

Sometimes we might be offended by what we find thumbing through the classics. Dirda notes the casual prejudice and bigotry one might encounter in old books. “No matter,” he says. “Read them anyway. Recognizing bigotry and racism doesn’t mean you condone them. What matters is acquiring knowledge, broadening mental horizons, viewing the world through eyes other than your own.”

Old books offer us the perspective of a different vantage point, one removed from our own moment. We can correct what we find in them, and they can sometimes correct what they find in us. C.S. Lewis wrote about that feature of old literature when introducing a new translation of Athanasius’s On the Incarnation, originally written in the fourth century. “Every age has its own outlook,” he says.

It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books. All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook—even those, like myself, who seem most opposed to it. Nothing strikes me more when I read the controversies of past ages than the fact that both sides were usually assuming without question a good deal which we should now absolutely deny. They thought that they were as completely opposed as two sides could be, but in fact they were all the time secretly united—united with each other and against earlier and later ages—by a great mass of common assumptions.

We can detour here to another book by Lewis, The Discarded Image, where he underscores this tendency in late classical culture among pagans and Christians. “They were in some ways far more like each other than was like a modern man,” he says. They “had the same education, read the same poets, learned the same rhetoric.” Sharing the same culture and formation, ancient pagans and Christians tended to share much of the same worldview. Lewis notes it’s sometimes difficult to tell if an ancient author of this or that book was pagan or Christian, so close were their perspectives.

And the same is roughly true today. We are shaped in a world of Western, liberal values influenced by deep undercurrents of Christian thought and practice. Whatever our disagreements with our neighbors, we share more than we realize and are usually blind to the commonalities.

Ideas circulate in certain times and places. Ages and decades, though not sealed off, can nonetheless act like echo chambers in which certain views and philosophies reverberate more loudly than others. We fix on them and find ourselves living in response to them whatever we think or assume about them. Books can either reinforce the bubble—or pierce it.

By focusing on prevailing messages to the exclusion of others, we become blind to—and forgetful of—other perspectives. Excluding old books can reinforce this dynamic. “None of us can fully escape this blindness,” says Lewis, “but we shall certainly increase it, and weaken our guard against it, if we read only modern books. Where they are true they will give us truths which we half knew already. Where they are false they will aggravate the error with which we are already dangerously ill.”

On the other hand, interspersing modern reading with classics can expose us to ideas that run counter to the prevailing culture, sometimes helpfully so. As such, Lewis suggests keeping “the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds.” How? “By reading old books.”

Of course, old does not equate to good, right, or true. People were just as prone to faults and foibles in the past as we are today. But, as Lewis says, authors of prior ages were prone to different errors than our own and also unlikely to affirm us in ours. In a sense, it comes down to crowdsourcing: “Two heads are better than one,” says Lewis, “not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction.”

It’s the very distance from our own times and perspectives, along with their particular blinders and biases, that make old books valuable. We don’t have to fear the follies and failings of old books; we’ll spot them easily enough. The value comes when they expose faults in us.

But, as Dirda goes on to explain, there’s more value to be had from old books than perspective and corrective. They can also be fun and refreshing, especially in heavy or difficult seasons. “The great books are great because they speak to us, generation after generation,” he says.

They are things of beauty, joys forever—most of the time. . . . The books of the past, besides adding to our understanding, offer something we also need: repose, refreshment and renewal. They help us keep going through dark times, they lift our spirits, they comfort us.

It was precisely this reason that led me to intentionally pick up classic novels the last few years. I started in 2023 and haven’t looked back. I only fault myself for not beginning a couple decades earlier. Now for 2026 I’m looking forward to a bigger challenge—literally. I’m finally facing twelve intimidating, hulking, big-ass classics. Details on those below.

I sometimes joke that I’ve started reading The Brothers Karamazov more times than some people quit smoking. It’s one of those books I’ve felt I ought to read but just can’t seem to turn past the hundredth page. This takes me back to Dirda’s essay. Yes, reading the classics is important but, he asks,

Does that mean you should devote your evenings to arguing with Plato, working your way through Dante and learning how to live from Montaigne? Being an idealist, I think you should, though certain classics—Samuel Johnson’s moral essays, George Eliot’s “Middlemarch”—are best appreciated in middle age, when they will pierce you to the marrow. Still, literature’s Himalayan peaks can be daunting. As the Victorian classicist Benjamin Jowett once said, “We have sought truth, and sometimes perhaps found it. But have we had any fun?” In reading as in life, fun does matter.

So, yes, struggle with the challenging books. But find some classics that are fun. Engaging with classic literature has some inherent difficulties; the distance posed by culture, language, and literary form can be tough to bridge. These difficulties are not insurmountable, however, and sometimes they exist in our expectations alone. Dostoevsky may have stumped me, but I actually find Montaigne hilarious at times and always interesting.

Once you get started, you discover some paths easier to walk than you first assumed; those intimidating Himalayan peaks reduce to gentle hills. The truth is I loved Middlemarch, and my favorite book from 2025 was Alessandro Manzoni’s possibly-daunting novel The Betrothed. One man’s mountain is another man’s molehill. Sometimes that’s even true of past us and future us.

And so Dostoevsky’s back on my menu for 2026, part of my big-ass classic novel challenge. Not The Brothers Karamazov this time, but Crime and Punishment. Some of you weighed in on the selections. Here’s my (mostly) final list:

January: John Steinbeck, East of Eden

February: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

March: Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

April: Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

May: Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

June: Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

July: Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate

August: Henry Fielding, Tom Jones

September: Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

October: Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White

November: James Joyce, Ulysses

December: George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

My hope is that this list represents a good mix of challenge and delight. If you want to read along, I invite you to join me. My plan will be to read and review each of these in the month indicated. Let me know what you think of this final list. And tell me what classics have meant the most to you.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

And check out my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future! Is it one of the best books published in the last twenty-five years? You’ll have to tell me. Interintellect founder Anna Gát calls it “the best Christmas gift you can get for anyone you know who loves books and ideas.” Who am I to disagree?

Well said, but I think it should also be said that many of the ideas and assumptions of the past were rooted in a very different economics. We stopped practicing slavery when we invented machines to do the hard work that slaves use to do. Slavery persisted, after most of the world turned against it, in places which relied on work that machines had not been invented to do, such as picking cotton.

We get squeamish about unpleasant things what we don't depend on (or don't realize we depend on) for our comfort and security, and we get callous and self-righteous about things we do depend on (or believe we depend on) for our comfort and security. We are not more virtuous than past peoples, and we now excuse horrors they would have roundly condemned; we are simply richer and can afford to be smug about the horrors they committed to secure their safety and comfort.

We need to take that lens to the study of the literature of the past. It may help us to see the planks in our own eyes.

Oh my. Your list is dauntingly ambitious, incredibly wild, and amazingly fun! I'm currently finishing East of Eden, and I read Crime and Punishment in June (I would highly encourage you to make a character list to aid you, as many characters go by multiple names!!), so maybe I can just start with Tristram Shandy and see if I can keep up. You INSPIRE me! Keep it up!