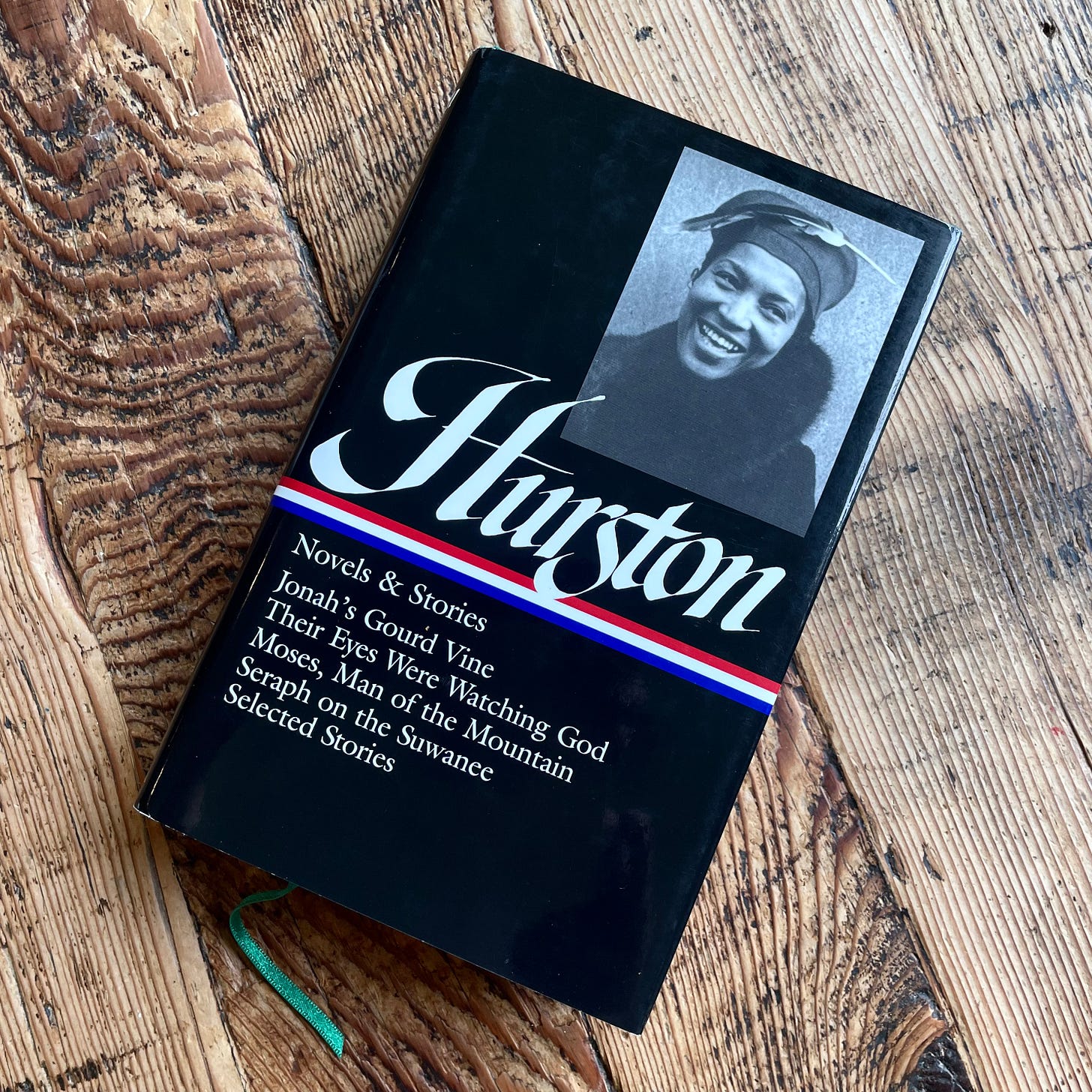

A Woman on Her Own, Joyously and Fiercely Independent

Reviewing Zora Neale Hurston’s Classic Novel, ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God’

How many copies had I sold? Dozens, easy. Probably a hundred, maybe more. “Do you have Their Eyes Were Watching God?” a high schooler would approach the counter and ask. I worked at the Almost Perfect Bookstore in Roseville, California, and my job was to sort, shelve, and sell books.

This was long before Amazon, and our storeowner was a shrewd businesswoman. We sold history, politics, religion, humor—all the stuff I was into. But you can’t keep a bookstore running on that kind of inventory alone. Our owner curated a vast selection of genre fiction, especially mysteries, romances, horror, and sci-fi, along with true crime. She also got the reading lists from all the high-school teachers in town and ensured we were stocked when students needed books—hence the steady stream of teenagers looking for Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 classic.

Alice Walker’s 1975 Ms. magazine article, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” called that memory to mind. Hurston lived out her final years in poverty and obscurity, dying in a welfare home in 1960 of heart disease after already having suffered a debilitating stroke. When Walker visited Hurston’s hometown of Eatonville, Florida, more than a dozen years later, she asked if Hurston’s books were taught in the local schools.

“No,” a woman answered. “I don’t think most people know anything about Zora Neale Hurston. . . . I’ve read all of her books myself, but I don’t think many other folks in Eatonville have.” How had Hurston gone from a faded memory in her own town to a mainstay on high-school reading lists across the country?

Zora and Janie

Hurston was born in 1891, though she lied and usually said she was born in 1901, 1902, or 1903, depending who asked and when. She seems to have fudged her age to attend high-school in her mid-twenties. Then again, according to her second marriage license, she was born 1910; was that a nineteen-year tug on the truth or just a bit of dyscalculia from a county clerk?

She was a headstrong child, whose stubbornness became one of her most enduring, if not endearing, qualities as an adult. “What she thought, she thought,” a friend recalled; “and generally what she thought, she said.” Nor did she care much who disagreed. As Eatonville was one of the first black-incorporated cities in the country, Paul Hond observes, “her worldview was shaped by the norms conferred by Black self-governance: citizenship, equality, and individuality.” She stood for her own views, joyously and fiercely independent.

There’s enough autobiography filtered through the settings and characters of Their Eyes Were Watching God to easily imagine Hurston as a young woman through the eyes of Janie Mae Crawford, the heroine of her story.

There are two Janies at the start of the novel: a middle-aged woman, walking back into Eatonville in a pair of overalls with her long black hair hanging down her back, and a teenager, awakening to the deeper questions of love, romance, and marriage. The novel’s drama involves the younger Janie’s winding journey back to Eatonville all those years later.

Hurston wrote the novel in a seven-week sprint while researching voodoo in Haiti on a Guggenheim grant. She’d pulled together an education at Howard University, Barnard College, and Columbia, ultimately focusing on anthropology and ethnography, disciplines that infused her stories with an authentic feel for people and an ear for their language. While she’d already traveled through Florida and Alabama for several years doing ethnographic work, this Caribbean jaunt was in part to escape a complicated romance with a Columbia student, Percival “Percy” Punter, many years her junior.

“This was my chance to release him, and fight myself free from my obsession,” she explained in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road.

He would get over me in a few months and go on to be a very big man. So I sailed off. . . . But I freely admit that everywhere I set my feet down, there were tracks of blood. Blood from the very middle of my heart. . . . So I pitched in to work hard on my research to smother my feelings. But the thing would not down. The plot was far from the circumstances, but I tried to embalm all the tenderness of my passion for him in Their Eyes were Watching God.

Passion is a central theme of the novel—what to do with it, how to respond to it, how it disappoints. It all begins with Janie’s amorous teenage awakening. Her grandmother Nanny with whom she lives, catches a local boy stealing a kiss and determines to marry Janie off and save her from an unfortunate fate. Both Janie and her mother are children of rape, and Nanny wants Janie under the protection of a respectable man—pronto.

Nanny has an older, widower farmer in mind, Logan Killicks. The match is soon arranged, and Janie finds herself wed. Miserably so. Killicks is less interested in a wife than a domestic servant.

Some time later, while Killicks is off buying a mule for Janie to plow his fields, a tall-talking man wanders by and promises to change her life. Joe Starks is on his way to Eatonville—an entirely black-owned, black-run, and black-populated town patterned on her own hometown—to make a name for himself. He wants Janie to run away with him. “He spoke for far horizon,” says the narrator. “He spoke for change and chance.” While she hesitates at first, Janie eventually capitulates; the pair absconds and marries.

Joe is a visionary, a quintessential big man, and has the whole town following his lead in no time. He opens a store and a post office and becomes mayor. He’s a riser, and he’s taking Janie with him. But only on his terms.

Janie, first wooed by Joe’s talk of liberation, becomes hemmed in and marginalized. Joe keeps her working in the back of the store, handling menial work, while he works the people and gets all the plaudits. He won’t even let Janie wear her hair down for fear the townsfolk will admire her beauty at his expense. From one loveless, restricted marriage to another: Janie longs for freedom, but there’s no way out.

The Freedom to Be

Hurston arrived in New York in 1925, and her larger-than-life presence made an impression on everyone active in the Harlem Renaissance, though not always positive. The same was true for her work. While she received early recognition and praise, some deemed her insufficiently serious.

Her ethnographic investigations and folklore studies found their way into Their Eyes Were Watching God, revealing itself through firecracker dialogue, expressions, and imagery. The characters speak in a riotous, colloquial dialect that can prove difficult on the page (though it’s pure joy to hear on audio). Some reviewers of the book, especially black reviewers, took umbrage at the portrayal.

Writer and arts advocate Alain Locke acknowledged its charms but lamented,

Her gift for poetic phrase, for rare dialect, and folk humor keep her flashing on the surface of her community and her characters and from diving down deep either to the inner psychology of characterization or to sharp analysis of the social background. . . . [W]hen will the Negro novelist of maturity, who knows how to tell a story convincingly—which is Miss Hurston’s cradle gift, come to grips with motive fiction and social document fiction?

Novelist Richard Wright was especially brutal:

Miss Hurston seems to have no desire whatever to move in the direction of serious fiction. . . . Miss Hurston can write, but her prose is cloaked in that facile sensuality that has dogged Negro expression since the days of Phillis Wheatley. Her dialogue manages to catch the psychological movements of the Negro folk-mind in their pure simplicity, but that’s as far as it goes.

After damning her “minstrel technique,” Wright added, “The sensory sweep of her novel carries no theme, no message, no thought.” Similarly, writer and critic Ralph Ellison decried the “calculated burlesque” in which “the casual brutalities of the South seldom intrude.”

In short, Hurston wasn’t on message. And she didn’t care. The same charges were leveled when she published her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, in 1934. Her response then works here as well. “Many Negroes criticize my book because I did not make it a lecture on the race problem,” she said. “I was writing a novel, not a treatise on sociology. There is where many Negro novelists make their mistake: they confuse art with sociology.”

Besides, the critics were wrong: Janie’s psychology is amply explored, and Hurston was, in fact, leveling social commentary and critique. Janie’s personal emancipation forms a major theme of the book, and this liberation is echoed by the worlds created by the African American characters in the novel. “Well aware of bigotry,” says legal scholar Randall Kennedy, Hurston “chose to portray the manner in which, in the midst of white oppression, blacks work to create their own way of life.”

These twin themes fly straight out of Hurston’s own life: She wasn’t going along with anyone’s idea of what she should do but her own. Ultimately, neither would Janie.

Storm Coming

After Joe and Janie had been married some twenty years, the big man finally dies, leaving his widow with the store and a sizable fortune. Though not interested in marrying anyone from Eatonville, Janie takes a shine to a handsome young suitor named Tea Cake, patterned on Percy Punter, whose memory Hurston wrote so feverishly to “embalm.” Could their ending be anything but tragic?

Though many years Janie’s junior, Tea Cake revels in her and convinces her to leave town and get married. The story shifts from one promised emancipation to another. In this next move, Janie finds a husband who seems to cherish, even idolize, her. But Tea Cake has his problems, too; he can be aggressive, unhinged, and take advantage of Janie’s affections. Unlike Killicks and Joe Starks, however, he’s fundamentally goodhearted despite his faults.

The pair move as migrant farmhands to the Florida Everglades. There in the climax of the story a hurricane kicks up and blows through. Tea Cake heroically saves Janie’s life but then meets his own demise through a turn so surprising I won’t ruin it for those unfamiliar with the story. As a sign she intends to live life on her own terms, Janie attends Tea Cake’s burial not in mourner’s black but a pair of overalls.

When this older Janie now walks back into Eatonville in that same pair of overalls, hair swinging free, her neighbors gawk and gape as she passes. Everyone has opinions. The passage provides a taste of Hurston’s musicality.

The people all saw her come because it was sun-down. The sun was gone, but he had left his footprints in the sky. It was the time for sitting on porches beside the road. It was the time to hear things and talk. These sitters had been tongue-less, earless, eyeless conveniences all day long. Mules and other brutes had occupied their skins. But now, the sun and the bossman were gone, so the skins felt powerful and human. They became lords of sounds and lesser things. They passed nations through their mouths. They sat in judgment.

Seeing the woman as she was made them remember the envy they had stored up from other times. So they chewed up the back parts of their minds and swallowed with relish. They made burning statements with questions, and killing tools out of laughs. It was mass cruelty. A mood come alive. Words walking without masters; walking altogether like harmony in a song.

Like Hurston with her critics, Janie just walks on by, letting them fill in whatever slanderous details they desire. Instead, she has her friend Phoeby to whom she can relate the entire story, and so she does, starting all the way back in Nanny’s garden. Unfortunately for Hurston, however, there was no one to hear her at the end—perhaps the final cost of her independence.

Hurston’s Resurrection

Hurston’s books never sold significant numbers during her lifetime. “She published five books in the 1930’s but never made more than $1,000 from any one of them,” said Randall Kennedy. All were out of print by her later years. Toward the end of her life, Hurston worked on a novel about Herod the Great. Publishers were uninterested.

Broke and mostly forgotten, she suffered a stroke and was unable to work. She died a charity case, buried in an unmarked plot in a segregated cemetery in Fort Pierce, Florida. But of course that was not the end of Zora Neale Hurston. She possessed too much vitality to die so prematurely, so anticlimactically.

There was a mini-renaissance of her work in 1970s. “Smudged photocopies . . . used to circulate, like samizdat, at academic conventions,” said critic Claudia Roth Pierpont. But then several of her novels finally found their way back into print. A copy of Their Eyes Were Watching God found its way into the hands of rising talent Alice Walker.

The poet and novelist who would later win a Pulitzer for fiction became curious about this writer for whom she had no information and began looking for details about Hurston’s life. Both women had stories featured in Langston Hughes’s 1967 collection, The Best Short Stories by Black Writers, just pages apart.

Walker’s first public outing with Hurston’s memory came in the form of the 1975 article I mentioned up top, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” in which she recounts her journey to find Hurston‘s unmarked grave. She successfully discovered it and paid for a marker. But Walker also erected a larger monument: her active advocacy of Hurston’s work. In 1979, Walker published an anthology of Hurston‘s writings with the wonderful title, I Love Myself When I Am Laughing . . . And Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive.

And so began the long remembering of Hurston’s life and work, eventually landing her the status of a great American novelist she long deserved—the kind of person who ends up on high-school reading lists. Time magazine lists Their Eyes Were Watching God in its “100 best English-language novels published since 1923,” and it made a BBC list of 100-best novels as well. In the period between 1990 and 1997, says Pierpont, Their Eyes Were Watching God sold over a million copies.

Though still contested and complicated, Hurston’s significance continues mostly because of her joyous, fierce independence. “What Hurston wanted, in both life and literature,” says legal writer Damon Root, “was for everyone, of every race, for better or worse, to be viewed as an individual first.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God is the eighth book in my 2023 classic novel goal. If you want to read more about that project, you can find that here and here. So far, I’ve read and reviewed:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (January)

Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (February)

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (March)

Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (April)

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (May)

Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (June)

Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy (July)

In September, I’ll be reading and reviewing Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Agree, this is excellent. I learned so much! I am always fascinated how little artists (writers, painters, etc) are appreciated in their life time. So often they are "discovered" afterwards.

Thank you for the essay. Does she contextualize the title at all? Why this title do you think? I have not finished reading it.