My new book, The Idea Machine, is out in the world, doing what good it will do. So far, the reaction has been extremely encouraging.

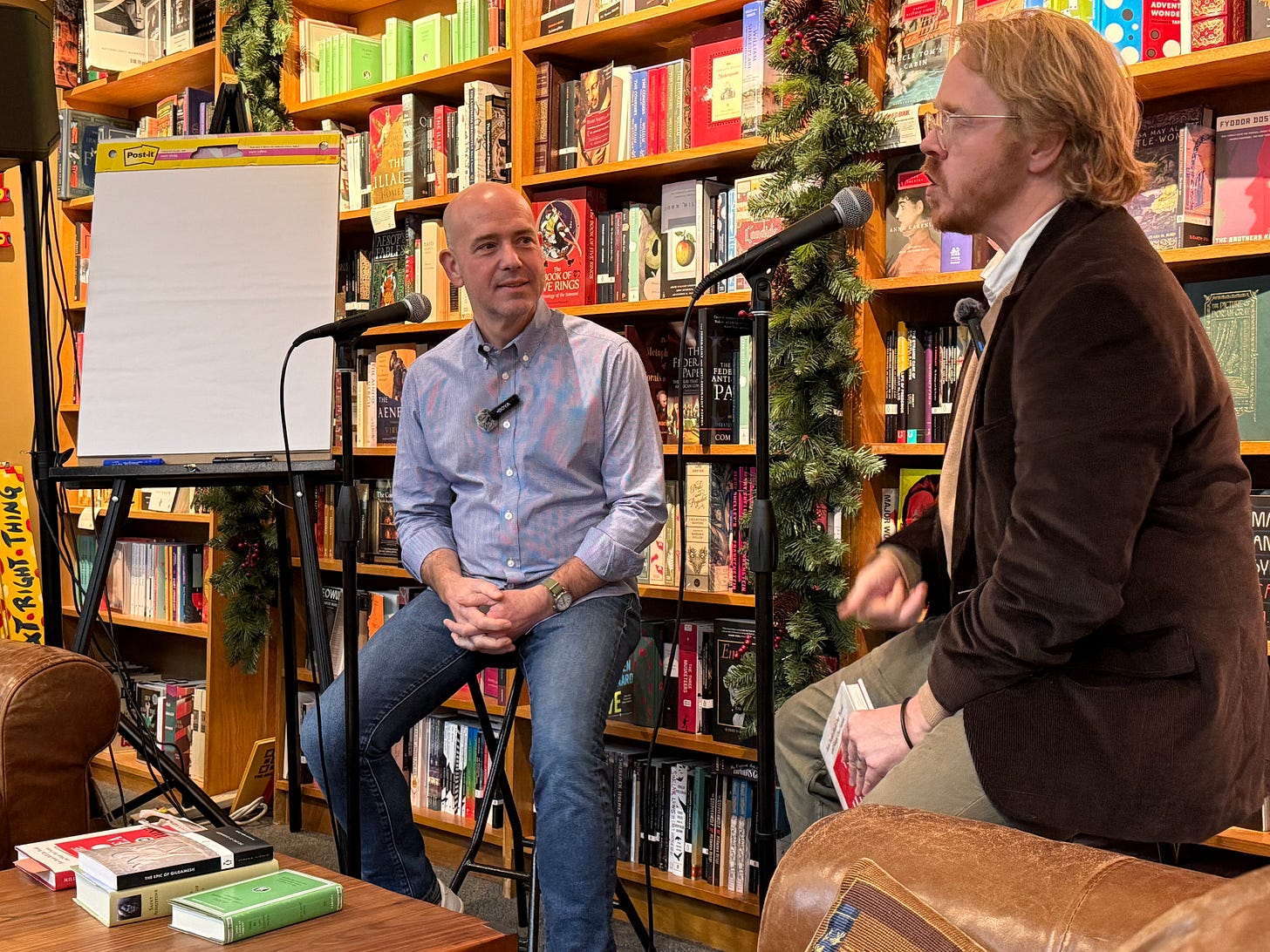

I want to share a bit of that with you, beginning with a conversation Jeff Goins and I had at Landmark Booksellers in Franklin, Tennessee, on launch night, November 18. Erik Rostad extended the invitation, and the evening couldn’t have gone better. You can listen to the exchange above. It’ll give you a flavor of the book, and I think it’s pretty fun. Hit play and enjoy the ride.

The Landmark Event

The conversation opened with my discovery of the book’s central angle when reading Augustine’s Confessions, specifically the moment when he breaks down in the garden and then salves his spirit by picking up a collection of St. Paul’s letters. I noticed how the thingness of the book—its ability to be opened at random, to hold a place, to be handed to a friend—enabled what he described. That material affordance of the codex itself became the lens for much of what I cover in The Idea Machine: In a phrase, the book is a critically important but underrated information technology.

I took some swings at Socrates, who criticized books while using them regularly—a hypocrisy worth highlighting and maybe chuckling over (I explore this in depth in the book). And I addressed Sam Bankman-Fried’s contempt for reading, noting that given his prison sentence for fraud, he might stand a reverse poster-boy for the humanities—or at least the smarts of not rejecting the sort of wisdom found in books. I hope he makes use of the prison library.

Jeff and I trace the long arc of information management from Ashurbanipal’s 30,000 clay-tablet library through the Library of Alexandria’s 120-volume catalog to Paul Otlet’s index card proto-internet and J.C.R. Licklider’s vision of “procognitive systems”—essentially describing how people use LLMs. A possibly controversial argument: LLMs aren’t a rupture from book culture but its latest iteration. Humans have always generated more data than we can manage, and we’ve always invented tools to retrieve and use it.

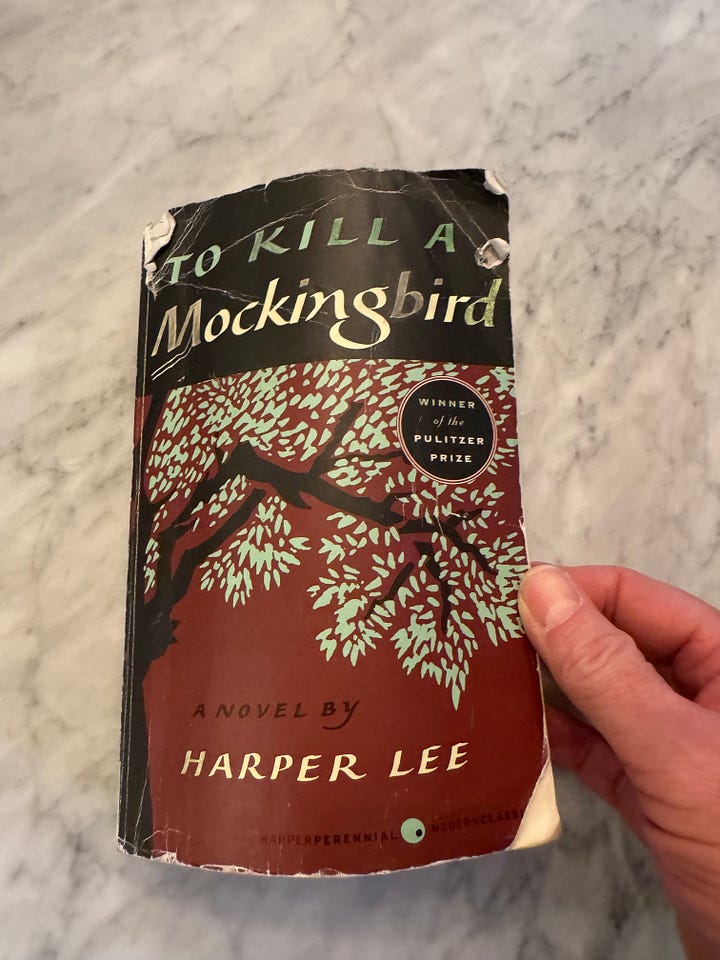

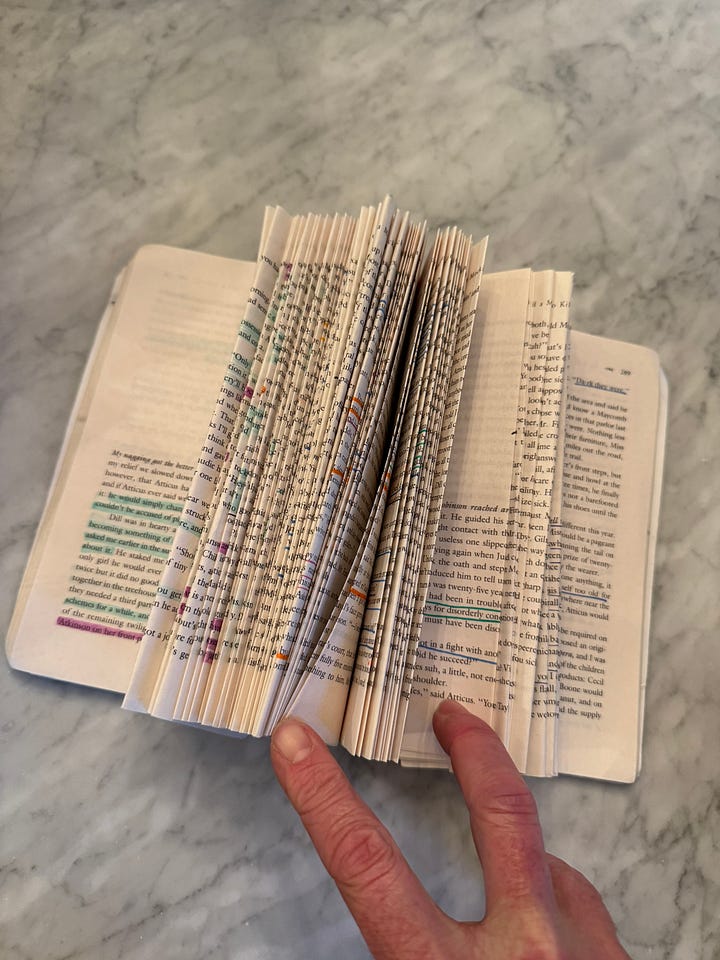

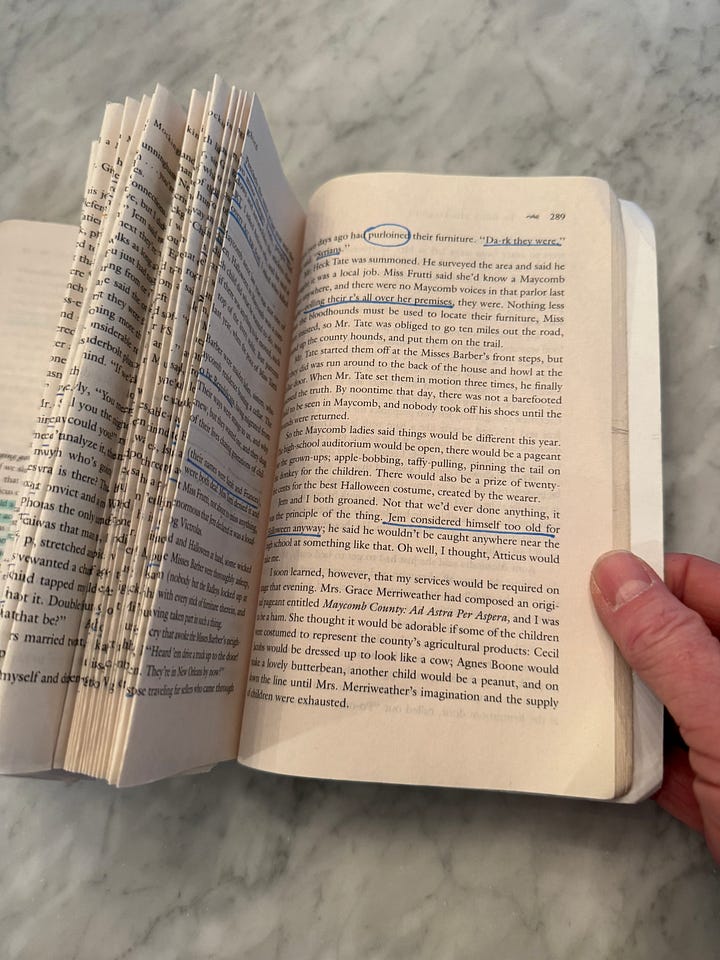

The practical question of how to read came up. My answer: write in your books. The page is designed for annotation. Create your own index. Dog-ear freely. A book is a technology meant to be used, not preserved under glass. I give you an extreme example here: my son Jonah’s well-used copy of To Kill a Mockingbird. Harper Lee would probably cry, but he’s loving the book.

I sketched a three-axis model—specificity, expression, and time—that explains several critical reasons books matter: they allow precisely formulated ideas to not only find audiences when first written but to persist across centuries, enabling, for instance, James Madison to design a constitution using political and legal histories and treatises Thomas Jefferson scooped up for him in the book markets of Paris, or Charles Darwin to amass the evidence he used in On the Origin of Species, not to mention countless other examples you’ll find in the book.

Jeff asked me about several books I recommend folks read. I’m always mixed on recommending books. How do I know what you should read? Jeff forced me. Luckily Landmark has an amazing feature: Behind us stood the Great Wall of Books, a chronologically arranged collection of classic texts; you can see it in the picture above. I recommended four: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Middlemarch, Till We Have Faces, and Jonah’s favorite, To Kill a Mockingbird. Jeff kindly recommended my own.

Others have as well!

Other Voices

The Saturday following the Landmark event, Anna Gát hosted me in New York for an Interintellect SuperSalon. Afterward she took to X and called The Idea Machine, “The best Christmas gift you can get for anyone you know who loves books and ideas” (hint, hint). Nick Gillespie, who I had the pleasure of seeing in New York, also praised The Idea Machine on X, calling it “a fantastic book by a unique and original thinker. . . . I highly recommend.”

I was very gratified to see that Andrew Spencer reviewed it for TGC: “Miller hits the bulls-eye as he shows the power of books to change the world by disrupting the status quo,” he said. “The Idea Machine is a timely reminder that the oldest tools, wielded well, may be the sharpest.” You can read the rest of the review here.

Booklist also has good things to say:

Miller elegantly demonstrates how books in their many forms have enabled the transfer of thought and elevated human experience. . . . Miller excels at synthesis, drawing a through line between medieval scriptoria, early printing, and modern publishing to show how ideas are shared and imaginations flourish. Readers of intellectual history will thoroughly enjoy.

Additionally, I found out yesterday that economist and world’s-most-curious-manTyler Cowen is reading the book. He has this to say:

A paean to reading and its importance, comprised of many historical anecdotes. I wish each part went into more detail, nonetheless this is an important book about a cultural transmission method that is in some unfortunate ways diminishing in its cultural centrality.

That was a treat. Actually, that’s understated; I’m suppressing unmitigated glee. I’ve been a fan of Cowen’s work for years now. It’s a thrill to see him engaging with the book and its argument.

Suzanne Smith reviewed the book for Front Porch Republic. A snippet:

His excellent new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, is motivated by two closely related problems. First, because books have become so familiar, we have forgotten to recognize “the book for what it is: a remarkably potent information technology, an idea machine.” Second, we have failed to appreciate the extent to which books served “as one of the most important but overlooked factors in the making of the modern world.”

Miller makes this argument via a dazzlingly wide survey of texts ranging from fourth-century BCE Greece to the present moment. The book is addressed to the educated general reader rather than a narrow audience of book historians or historians of technology. . . . Every part of this book holds significant rewards. Despite the vast scope and density of detail, Miller writes with consistent verve, and he eloquently defends the book against those who would dismiss it as being of historical interest.

Smith provides a thorough examination of the central argument of the book, and brings several sources into the conversation to enrich it. I’m deeply gratified by her approach. Read the rest here.

More from Me

Greta Dieck asked me a bunch of interesting questions for The Republic of Letters, which I eagerly answered. Here’s part of one of my responses:

Literature has a major role to play in grounding us and elevating humane concerns in a digital age. AI can be trained on the artifacts of our suffering, frustration, elation, and successes. But they can’t experience them firsthand or convey them as humans might. Nor can they be properly skeptical. That’s a human strength worth nurturing. We give Doubting Thomas too much grief. As Thon Taddeo says in A Canticle for Leibowitz, “A doubt is not a denial. Doubt is a powerful tool, and it should be applied to history.” And everything else, probably. Critical engagement with books can sharpen that skeptical sense.

[. . .]

Humans have another wonderful feature. We can set a goal for ourselves and then blow it off. Boethius was planning to translate gobs of Aristotle into Latin. When he was arrested and jailed for treason, he had all the time he needed to work on the goal. Instead, he wrote The Consolation of Philosophy and gave us a book that still resonates today. Humans can follow whims—and that’s where the magic usually is. That way lies not madness, but delight.

You can read the rest of the conversation here.

Finally, Reason magazine, which I’ve been reading since my teens, excerpted a portion of the book for their January print edition. The good news? You can read it online now! The focus of the excerpt is on the explosion of books occasioned by the printing press. Some of the problems included sorting and arranging that supernova of content. How could a person find what they were looking for in libraries and collections that suddenly swelled with titles? I cover some of the solutions. I also cover the other side, those who wanted to squelch the speech of books they disagreed with. An excerpt from the excerpt:

When anti-Catholic German peasants rose up in 1524, their first targets included monasteries; since monks were heavily involved in book production, the peasants singled out libraries for destruction. After one Cistercian monastery in Herrenalb was ravaged, no one could enter the ruins without finding shredded, dismembered books underfoot. Some monasteries lost thousands of books, their shelves having been swollen by the recent arrival of print. Easy come, easy go.

In England, the theft of monastic holdings was a formalized process sanctioned by the government. After the Act of Supremacy in 1534, monasteries were dissolved and their property—including books—seized. The gentry and merchants bought up the assets and disposed of them however they saw fit. Collectors valued some of the books, but countless treasures ended up destroyed, used in some cases to rebind other books, clean boots, polish candlesticks, and serve even lesser ends. Some found their way to lavatories, recycled one scratchy page at a time.

There’s more to the story, involving book bans and the impossible challenge of enforcing them. If you want a taste of what’s in the book, this excerpt is a great place to start.

Now, Asking a Big Favor of You

When I began working on the launch for the book, I overlooked something major: I didn’t line up Amazon reviews in advance. Often publishers or publicity teams create “street teams” to push new books on social media and in reviews. I didn’t do that. If you’ve read the book, I’d like to ask you to jump over to Amazon and leave a review. No pressure for a glow-up. Say what you really think. It doesn’t have to be overly long or involved; just share your honest opinion of the book.

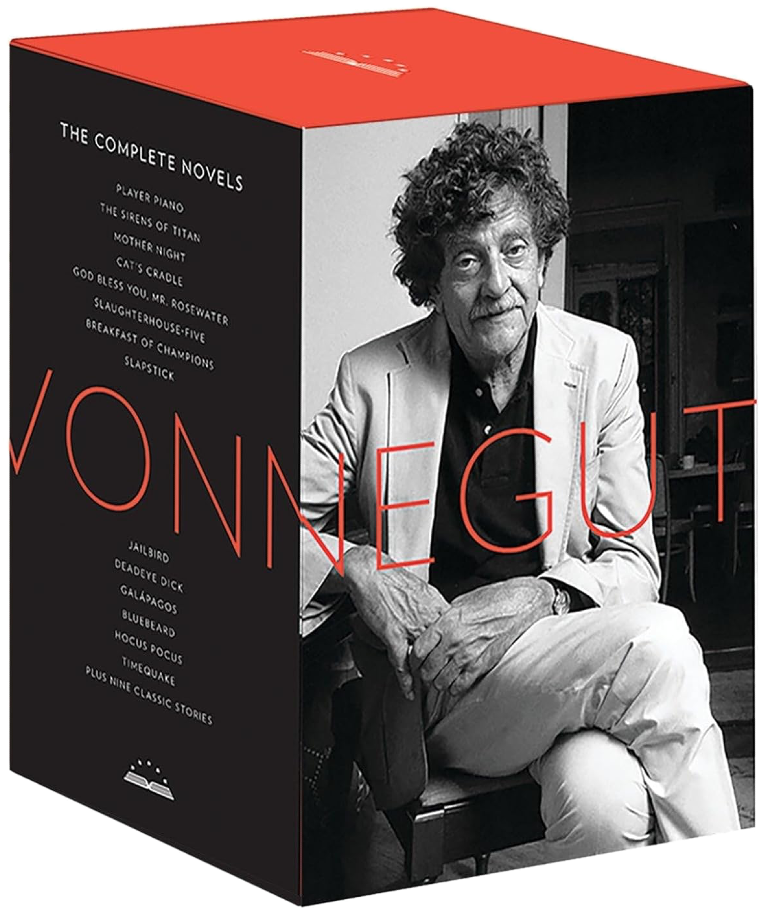

In exchange, I’ll enter you in a drawing for an autographed copy of The Idea Machine and a brand new Library of America Kurt Vonnegut boxed set. The set includes four volumes with fourteen novels, plus short stories: Player Piano; The Sirens of Titan; Mother Night; Cat’s Cradle; God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; Slaughterhouse-Five; Breakfast of Champions; Slapstick; Jailbird; Deadeye Dick; Galapagos; Bluebeard; Hocus Pocus; and Timequake. You can see more about the set here.

All you have to do to qualify for the drawing? Leave a review of the book here and email me a screenshot of the review. Opportunity to join the drawing will close December 19. I’ll randomize all entries and select the winner on December 20.

And if you’re on social media, please share about the book as well—Substack Notes, X, Instagram, Facebook, wherever. It’s hugely gratifying to see readers post images of the book. It’s also super helpful for raising awareness.

I’ve done a handful of great podcast interviews so far, but if you have a podcast and would like to discuss an interview, DM or email me. Same goes if you’d like to review the book for your own newsletter. Reach out and I’ll get you a review copy.

A thousand thanks!

And if all of this is news to you, you can find out more about The Idea Machine here.

Thanks for reading! Want to add thoughts of your own? Comment 💬 below.

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!