Worse Than Jerks: Why Some People Have Rotten Character

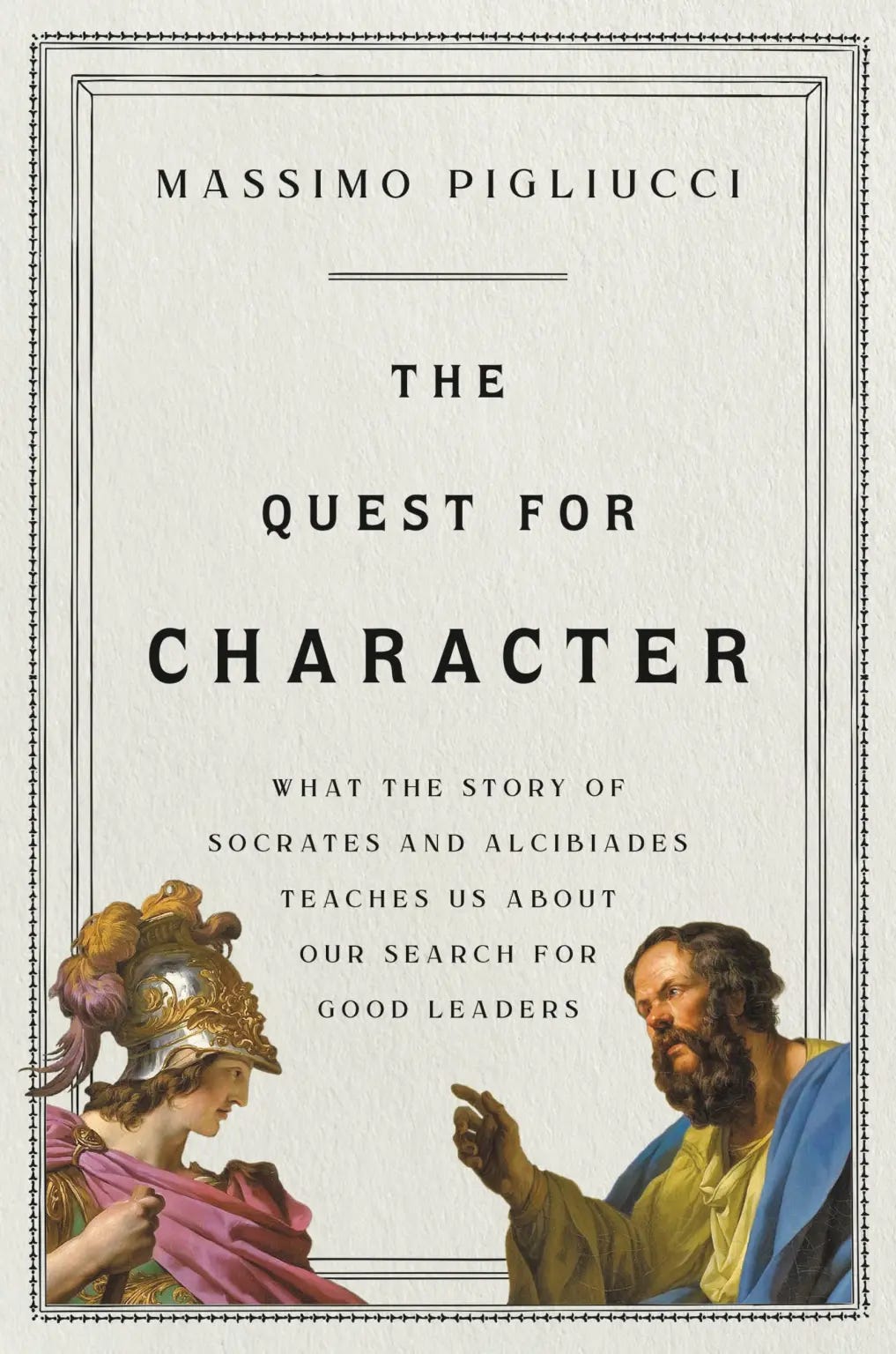

And Why Socrates Couldn’t Fix It: Reviewing ‘The Quest for Character’ by Massimo Pigliucci

At the risk of sounding unnecessarily crass, it’s worth considering the moral implications of philosopher Aaron James’s book, A—holes: A Theory, in which he attempts to define the unique characteristics of his titular subject. We mostly identify such people by experience and feel. They’re a step beyond a jerk; they cut us off in traffic, troll people mercilessly on X, insult the waitstaff, and proclaim their virtue while lying, cheating, and slandering.

But impressions of offense aren’t good enough, says James. He wants precision and offers three key attributes of how such a person conducts himself. Such a person, says James,

(1) allows himself to enjoy special advantages and does so systematically; (2) does this out of an entrenched sense of entitlement; and (3) is immunized by his sense of entitlement against the complaints of other people.

We usually need more evidence than a negative interaction to apply the appellation. But armed with James’s definition, we can all cite examples: maybe a celebrity in the news, someone at work, a politician with more faces than Mom provided at birth. The point is that the person knows the rules of good behavior but considers themselves above those rules.

Case in Point

James is happy to name names. But one name that goes unsaid in his book belongs to the fifth-century Athenian statesman and general, Alcibiades, a poster boy for his theory. Born into a prominent family—one whose members financed the Oracle of Delphi, source of the dictum “know thyself”—Alcibiades flexed his sense of privilege his entire life.

He once shellacked an elder, honored member of the community—on a bet. He then repaired the relationship, married the man’s daughter, and then pressured the family to up her dowry when she became pregnant with his child. He neglected his wife and frequented prostitutes. When she (reasonably) abandoned their home, Alcibiades dragged her back, publicly shaming her all the way.

He cheated friends, lied as a matter of course, and double crossed his city, Athens—more than once—while rationalizing his actions on the basis of his patriotism. He checks every one of James’s boxes several times over. The moral implication: Alcibiades possessed rotten character. And it had disastrous consequences for his fellow citizens.

What makes the life of Alcibiades so interesting is that his mentor and teacher was none other than Socrates. Surely, the gadfly of Athens could straighten him out. But no. And that fact drives the central question of philosopher Massimo Pigliucci’s book, The Quest for Character: What the Story of Socrates and Alcibiades Teaches Us About Our Search for Good Leaders: Is it possible to teach good character, to ourselves and others?

Mixed Results

Socrates tried. He knew his student’s wayward tendencies. We have reconstructions of some of their conversations. Socrates teases, implores, and directs Alcibiades to recognize his failings and make amends. He points his pupil back to the Delphic Oracle: know thyself. If Alcibiades refuses, says Pigliucci,

he will realize that the very things he considers to be his assets—beauty, height, family, wealth, and wits—are actually his worst enemies. And one more thing will hamper Alcibiades throughout his life: his boundless ambition.

Alas, Alcibiades ignores his teacher. But maybe others fared better with their students than Socrates. Pigliucci surveys several additional cases in the classical world, starting with Plato and the tyrants of Syracuse, Dionysius I and Dionysius II. Despite Plato’s best efforts these two rulers never developed the necessary character to lead justly. Dionysius II showed promise but did not maintain, as Pigliucci says, the “moral stamina” to reform his character.

Aristotle fared better with Alexander the Great, and his student certainly amounted to more. As a youth, Alexander displayed an eagerness to learn and grow; he was practical and smart. But as he grew, so did his ambitions, which ultimately undermined him.

Seneca’s student, Nero, gets the award for infamy. While starting strong, the emperor eventually descended into paranoia, murdered his own mother, and then commanded his teacher to commit suicide. So, there’s that.

In each case philosophers had the specific task of developing good character in their students and failed, sometimes spectacularly so. But what if we cut out the student? Pigliucci examines what happens when philosophers themselves lead. Theoretically, they don’t have to learn good character; they already have it. Cato gets high marks, as does Marcus Aurelius. Pigliucci considers Julian the Apostate, trained as a philosopher, a success as well.

If we’re looking for leaders with character, the case studies are mixed. It does seem clear, however, that crummy leaders are not apt to develop sterling character once in office; it’s unlikely at the very least.

Closing the Gap?

Based on what we’ve seen, developing good character proves challenging at minimum. Without intentional cultivation and maintenance of that character once in office, results fail to inspire. But we’re not without hope.

Pigliucci points to the work of another philosopher, Christian Miller, to show what does seem to work—particularly three strategies with empirical backing:

Following the example of good role models.

Placing oneself in situations that inspire virtue.

Exercising self-reflection.

I’ve read and strongly recommend Christian Miller’s work, but it’s worth saying: None of these are foolproof. Alcibiades had a good role model in Socrates, who not only mentored him but also modeled bravery, humility, and self-sacrifice beside him on the battlefield. He found himself in plenty of situations that inspired virtue. And not only did his own family build the sanctuary at Delphi, source of the injunction to know thyself, but Socrates encouraged him to do so.

The missing ingredient seems to be desire. If asked in the words of Cole Porter’s 1948 song, “Why Can’t You Behave?” Alcibiades’s honest answer would have been, “I don’t really want to.” And that pulled him away from his mentor, placed him in situations that encouraged vice, and squashed true self-reflection.

A Counterargument

All that said, can we excuse Alcibiades? Are we holding him to an unfair standard? After all, one might argue, the ancient Greeks were concerned primarily with acquiring glory; Alcibiades’s conduct could thus be taken as laudatory, rendering my critique misguided.

I don’t think so. Even on Alcibiades’s own terms of glory-seeking, he’s a scoundrel. Socrates saved Alcibiades’s hide during the Battle of Potidaea in 432 BCE. Here’s Plutarch’s account:

While still a stripling, [Alcibiades] served as a soldier in the campaign of Potidaea, and had Socrates for his tent-mate and comrade in action. A fierce battle took place, wherein both of them distinguished themselves; but when Alcibiades fell wounded, it was Socrates who stood over him and defended him, and with the most conspicuous bravery saved him, armor and all. The prize of valor fell to Socrates, of course, on the justest calculation; but the generals, owing to the high posit of Alcibiades, were manifestly anxious to give him the glory of it. Socrates, therefore, wishing to increase his pupil’s honorable ambitions, led all the rest in bearing witness to his bravery in begging that the crown and the suit of armor be give him.

Rather than disown the honor—which he hadn’t earned—and insist Socrates receive it instead, Alcibiades accepted the reward as if it were his due. A true seeker of glory would never assume honor due another. “The episode tells us something important about both Socrates’s and Alcibiades’s characters,” says Pigliucci about this moment.

Socrates showed incredible courage in battle as well as loyalty to his friend, who was in great difficulty. In the aftermath of the battle, he also acted in accordance with his philosophy: External things, such as medals and praise, are simply not important. What is important is to do the right thing. Alcibiades, by contrast—while also certainly brave in battle—just as clearly showed that his priorities were precisely the reverse of those of his mentor. He craved recognition and praise, even at the cost of taking it away from his own friend and savior, who obviously deserved it far more. These contrasting patterns would mark the entire lives of the two men.

Any way you look at it, Alcibiades was worse than a jerk.

The Persistence of A—holes

Whatever standard we apply, scoundrels are scoundrels because—back to Aaron James—they (1) systematically allow themselves “enjoyment of special advantages”; (2) do so “out of an entrenched sense of entitlement”; and (3) employ their “sense of entitlement” to immunize themselves “against the complaints of other people.” Sound like anyone you know?

Some people don’t develop decent character because they simply don’t think it applies to them, regardless of what others expect or insist. When faced with the character gap, they shrug it off and go about their business, regardless of who’s in the way or what consequences result, causing the gap to grow and their character to further erode.

Which leaves us with another question: How can we limit their negative impact on the rest of us?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

And make sure to tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future.

Alcibades' poor wife tried to limit his impact on her and couldn't. Thankfully, women are not considered their husband's property in law anymore, and so there is a way of escape. But it would be better not to be married to such a man in the first place. Alcibades' wife wouldn't have had much of a choice, marriages were arranged by families in ancient Athens. But modern women do, and as a result, there is a small, but vociferous group of scoundrel men who, feeling cheated of their idea of a properly submissive wife, want to return to the ideas of forced marriage and wife-as-property.

Bonus points for mentioning Cole Porter. There's the rub: changing our wills, not just changing our minds.