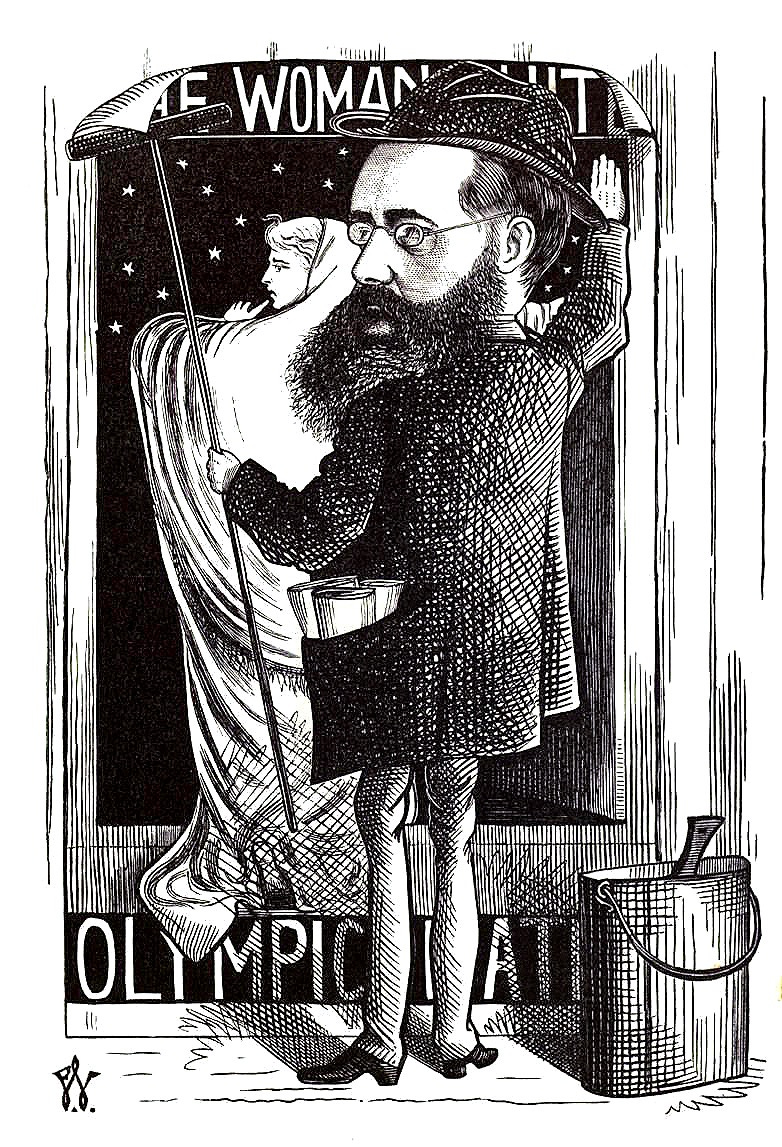

The Novel That Kept a British Prime Minister Up All Night

Wilkie Collins’s ‘The Woman in White’ Paved the Way for Modern Suspense Novels—And Then We Mostly Forgot

The artist Walter Hartright tramps homeward to London one sultry night from a farewell visit with his mother and sister, the moon overhead providing the only light along the way. The following day, he’ll trek north to Cumberland for a new job at Limmeridge House, teaching a pair of young ladies to paint. His friend, Professor Pesca, a political refugee from Italy, has secured him the position.

As his mind whirs on the prospects and the possibilities, his reveries are interrupted. A woman, clad head to toe in white, appears from nowhere on the road just behind him and, unannounced, lays a hand on his shoulder. To say Walter’s unsettled is an understatement.

“Every drop of blood in my body was brought to a stop by the touch,” he recounts. By the end of the story, the woman in white will have unsettled many others.

Anne Catherick, as we come to know her name, asks for help but remains elusive about her reasons. Clearly agitated, she frets about barons, though she won’t elaborate, and—startling Walter for a second time—seems to know all about Limmeridge House, though he’s told her nothing more than that he’s headed to Cumberland. Pure coincidence, and the first of many that will prove anything but innocent.

The mystery of the woman only deepens when they arrive in London. Walter hails her a cab and, seconds after the horse-drawn carriage rattles off, finds that she’s being pursued by two men in another carriage. Across the street a policeman walks his beat, and the men ask about a woman in white. Standing in the shadows, Walter overhears:

“She has escaped from my Asylum.”

Domestic Terrors

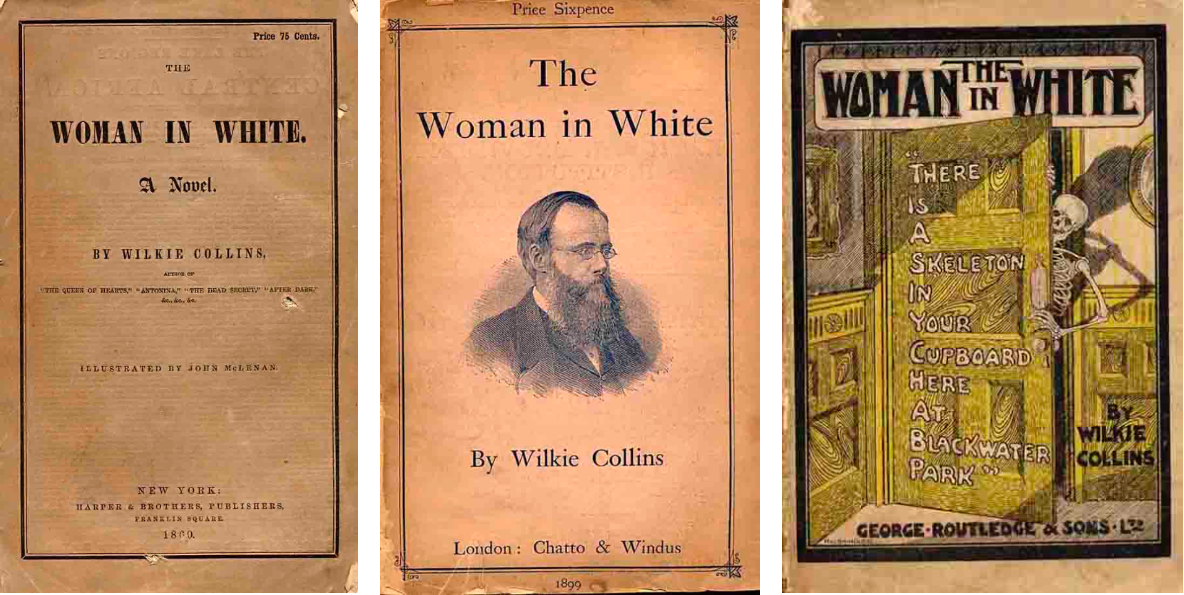

When readers first encountered the woman in white on a London road in November 1859, they were spellbound. Wilkie Collins’s tale, serialized over nine months in Charles Dickens’s All the Year Round, gripped them with a new kind of suspense.

For the last hundred years, novelists had been toying with readers’ fears by dragging them away from Enlightenment rationality and into ruined castles and crumbling abbeys in faroff settings for uneasy encounters with the eerie and uncanny. Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) unfurls in an Italian castle where a monstrous supernatural helmet crushes its victims; Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) sends its heroine into a dark Apennine fortress stalked by bandits and haunted by the seemingly supernatural; Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796) revels in a Spanish monastery rife with demonic bargains and the revenant of a bleeding nun.

As the period progressed, novelists played with the form to anticipate developments in reader anxieties. Mary Shelley kept the foreign locales for Frankenstein (1818, 1831) but revised the standard Gothic tropes by including the prospect of science itself gone wrong.

And then there’s Collins, who despiritualizes the story entirely, while keeping the core question posed by Gothic narratives: What if everything isn’t as buttoned up and rational as the Enlightenment promises? But instead of decadent lands and demonic pacts—the old world haunting the new—he centers his terrors in English country homes, down London streets, aboard trains, across the desk of lawyers, and in asylums whose everyday normalcy and respectability mask treachery, fraud, coercion, identity theft, possibly murder.

What happens to a woman’s safety when the very rules, norms, and laws of a rational, enlightened society can be bent into instruments of predation? To ask the question is to return to Walter’s painting pupils, Laura Fairlie and her half-sister Marian Halcombe.

A Warning Unheeded

When Walter arrives at Limmeridge, he’s instantly taken by the elegance of the house—and its female inhabitants. Better to say he’s smitten. While he guards himself against falling for his student, he succumbs to fascination with Laura.

I should have remembered my position, and have put myself secretly on my guard. I did so, but not till it was too late. All the discretion, all the experience, which had availed me with other women, and secured me against other temptations, failed me with her. It had been my profession, for years past, to be in this close contact with young girls of all ages, and of all orders of beauty. I had accepted the position as part of my calling in life; I had trained myself to leave all the sympathies natural to my age in my employer’s outer hall, as coolly as I left my umbrella there before I went upstairs.

Yeah, not this time. Walter, as they say, falls hard. Bad news because Laura is already betrothed to the baronet Sir Percival Glyde. She doesn’t love the man; in fact, she feels drawn to Walter, but Laura’s late father arranged the match and she implicitly trusts him to steer her fate, even after death, even against her heart, even after a shocking warning from an unnamed whistleblower.

A letter arrives at Limmeridge House purportedly recounting a dream. Glyde, the letter warns, is a fraud. Worse, he’s preying upon Laura. She has a lot to lose, including a sizeable inheritance. But is the letter trustworthy? After some sleuthing, Marian turns up the identity of the writer: none other than Anne Catherick, the mysterious woman in white—who we must pause to mention bears an uncanny resemblance to Laura. The two could be sisters, nearly twins.

Anne Catherick’s warning goes unheeded, and the wedding proceeds with the blessing of Laura’s guardian, her uncle, the feckless Frederick Fairlie, lord of Limmeridge House, who because of his psychological, physical, and moral frailty can’t be bothered to defend his niece’s interest. Walter departs England to serve as an illustrator on a naturalist expedition to Central America, and Laura joins her husband at his estate, Blackwater Park. (Cue the suspenseful string arrangement.)

Secrets and Conspiracies

Installed at Blackwater, Laura finds her husband less solicitous than during courtship. He haunts his own manor with his friend, the outlandishly colorful Italian Count Fosco, and Fosco’s wife—Laura’s Aunt Eleanor—who obeys her husband’s every whim, rolling him endless cigarettes while he plays with his birds and pet mice. The only saving grace from the social suffocation? Marian is allowed to live at Blackwater to keep the new bride company.

It’s euphemistic to compare Glyde’s finances to a shambles. He’s nearly ruined and dependent upon Laura’s inheritance, which, thanks to Mr. Fairlie’s negligent handling of the prenuptial agreement, is all but his. He has deeper secrets to hide, but stealing his bride’s fortune at least buys him time. Count Fosco is all too happy to help with the theft, and a bold conspiracy soon spins out in every direction, rendering Laura helpless.

Marian learns of the plan, or at least some of it—risking her life by crawling across a roof in a rainstorm—to overhear their scheming, but is taken by a sudden illness and unable to act in time. All the while Anne Catherick is active, trying to intervene from the margins but similarly unable to prevent the worst. She fears Glyde and Fosco for reasons of her own, going back to Glyde’s deeper secret—which she seems to know. Crossing paths with him before is what landed her in the asylum, a move to keep her quiet.

After her escape from the asylum, the only way to secure Anne’s silence is death. But even here Glyde and Fosco have their schemes. Who actually dies, Laura or Anne? And how can the victim’s identity be proved one way or the other? Glyde and Fosco bury the truth under a tombstone of deception that only but the most determined could ever uncover.

A Contest of Wills

Collins structures the story as a string of overlapping written legal testimonies—some of them conflicting—from the individual participants in the case, a novelty at the time. This allows the reader to participate in the unfolding mystery, guessing about the conspiracy, weighing evidence, and trying to puzzle out the intricacies of the crime and the deep secret behind it all.

Collins brings all these voices together in a contest of wills with a woman’s life—really two women’s lives, both Laura and Anne’s—in the balance. It is, as he says at the beginning, “the story of what a Woman’s patience can endure, and what a Man’s resolution can achieve,” particularly when “the machinery of the Law” fails.

The weakest will belongs to the maddeningly disappointing Frederick Fairlie. His negligence paves the way for the nightmare that follows. A more attentive uncle would have noticed the warning signs. A better guardian would have investigated Glyde before the marriage. But as far as Fairlie is concerned, the whole world can collapse as long as it doesn’t disturb his fragile nerves and delicate constitution: the picture of abdication.

Glyde and Fosco represent the corrupt wills, ready to take advantage. A desperate, volatile, and stupid man, Glyde is driven by the need to manage his crumbling finances while preventing the world from discovering the truth of his past. He’ll stoop to practically any shameful deed to salvage his reputation, including an audacious fraud requiring a more stable and agile mind than he possesses.

Enter Fosco, Glyde’s opposite in every respect—excluding the gaping moral vacuum at the center of his being, a feature both men share. Fosco lives within society and also far above it with no real concern for its scruples or laws. “The fool’s crime,” he opines at one point, “is the crime that is found out, and the wise man’s crime is the crime that is not found out”—the novel’s contest in a nutshell. And yet Collins’s arch villain is a literary treasure: larger than life, romantic, flamboyant, cultured, hilarious. The perfect sociopath, he admires Marian to the point of mild infatuation while plotting to destroy her sister.

The resolute wills? Anne Catherick never backs down in her brave but ultimately misguided attempt at exposing Glyde. But it takes the dogged determination of both Marian and Walter to counter the combined force of Glyde and Fosco. Marian’s courage—one of the greatest displays of female gumption in Victorian literature—holds the line during the crisis, while Walter methodically works to dismantle the conspiracy. Driven both by his love for Laura and his conviction the wrong must be righted, he refuses to back down even when his own life is threatened.

“It is my duty to tell you,” a solicitor informs Walter, “that you have not the shadow of a case.” Walter persists until he does.

I resist the urge to signal the conclusion, but will offer a tease. Glyde comes to an end worthy of the greatest Gothic novels, and Fosco has an unfortunate encounter with Walter’s old friend, Professor Pesca; we’ve all seen enough mob movies to know how the Italians manage justice when the justice system falters. Fosco’s was a fool’s crime, after all.

Fairlie’s weakness, Glyde’s fraud, and Fosco’s brilliance are all, in the end, insufficient. What prevails is the stubbornness of two people who refuse to accept a lie and possess the perseverance to expose it.

Treading on Bombshells

“Habits of literary composition are perfectly familiar to me,” Fosco announces before providing Walter an essential piece of evidence. “One of the rarest of all the intellectual accomplishments that a man can possess is the grand faculty of arranging his ideas. Immense privilege! I possess it.” So did Collins.

The labyrinthine plot with its countless trails and first-person narrators trapped in their limited perspective transfixed me for the duration. It’s long (a precondition of this project), something like 250,000 words, but as the suspense builds the pages fly past until you find yourself staring at the closing line and the surprising comeuppance. One 1863 reviewer compared the reading experience to “treading on bomb-shells, which may explode at any moment.”

Other reviewers tended to criticize, but the public raved. The final installment of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities appeared in the same issue of All the Year Round that launched The Woman in White. Dickens was hoping to keep subscribers happy, and Collins’s propulsive plot did the work. The installments ran for nine straight months with readers lining up at the offices of All the Year Round on publication days. They couldn’t get enough.

The attention held through the novel’s publication in book form in August 1860; by the end of the year, the publisher had ordered eight printings. British Prime Minister William Gladstone cancelled a night at the theater to finish it. And Vanity Fair author William Makepeace Thackeray reportedly stayed up all night reading it.

Henry James credited Collins with introducing “into fiction those most mysterious of mysteries, the mysteries of which are at our own doors.” Collins demonstrated that the terrors of fiction could operate in domestic spaces rather than in ruined castles, and that a story could be told through layered testimony instead of omniscient narration, that a plot could pivot on the procedural investigation of scanty evidence.

We’re accustomed to all these techniques today in crime fiction, thrillers, suspense, mysteries, and more. In fact, the literary world has so thoroughly metabolized those innovations we hardly know where they came from. But they start with Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White and his domestication of the Gothic.

I’m reading twelve big-ass classic novels this year. Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White is the second. Here’s the full schedule for 2026.

January: John Steinbeck, East of Eden

February: Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White

March: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

April: Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

May: Henry Fielding, Tom Jones

June: Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

July: Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

August: Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

September: Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

October: Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate

November: Denis Johnson, Tree of Smoke

December: George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends (or enemies, I’m not picky).

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

And check out my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, one of Big Think’s favorite books in 2025. I spend a whole chapter on the transformative power of fiction.

Collins' sensational masterpiece was deeper than it looked. The sinister plot in the Woman in White is possible because of the property laws that constrained a married woman in 19th century England - unless her inheritance was tied up in trust, a woman's property became her husband's upon marriage. Ten years after Collins' fictional sensation, John Stuart Mill, famous for writing On Liberty, would blisteringly observe in The Subjection of Women that the legal constraints binding women in marriage rendered them essentially domestic slaves.

Collins never again combined sensationalism with social critique with such success. The Moonstone uses the same narrative technique of collected testimonies, but is more of a detective novel. Collins wrote other social problem novels, but the social commentary started to drown out character and plot development. As one wit quipped:

"What brought Wilkie's genius nigh perdition? Some demon whispered, Wilkie, have a mission."

Joel, what a fabulous deep dive into ' masterpiece (although the Moonstone is just as fantastic). Wonderful to discover all the details surrounding the publication. Longing to pick this one back up now. (Also, how in the world are you going to read War and Peace in a month and still get anything else done?)