The Ancient Roman Guide to Building Your Personal Library

6 Ways to Assemble an Enviable Book Collection in a World Long Before Amazon

At the close of December, my social media feed bulges with pics of books, stacks of them, gifts from various and sundry. I contributed to the mix this year, posting a shot of several big-ass classic novels requiring more than a little shelf shuffling before they’d squeeze into my library (part of the haul included a three-volume set of War and Peace and a four-volume set of In Search of Lost Time).

No complaints from me!

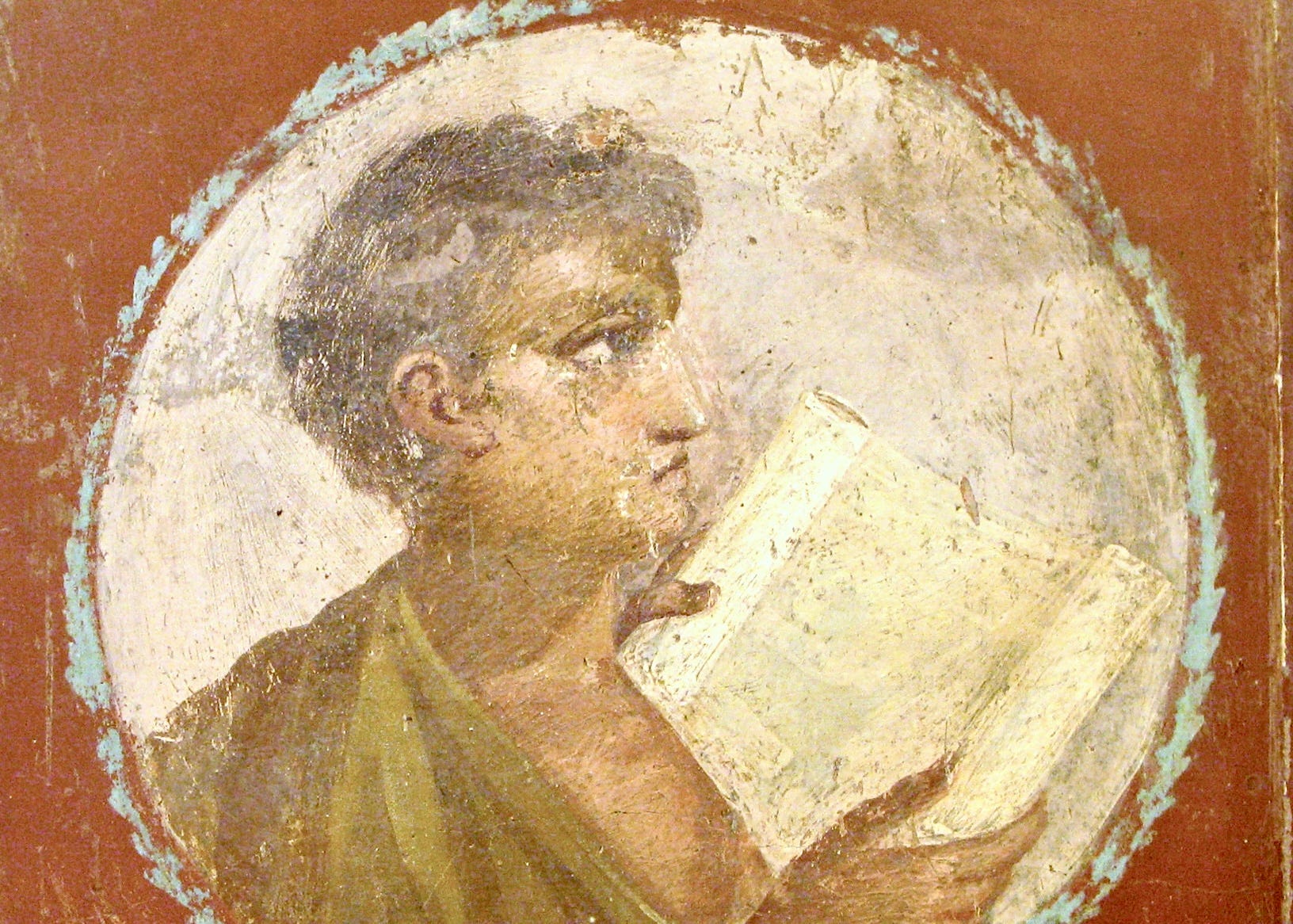

Receiving books is one of the more delightful ways to build a personal library. In fact, we’ve been amassing libraries this way for thousands of years. In the first century of the common era, Roman poet Martial wrote a string of poems discussing potential gifts for Saturnalia; he included books in the rundown. Who wouldn’t enjoy receiving an unexpected volume of Homer, Vergil, Menander, Cicero—or even Martial? He’d be tickled at the thought.

Beyond gifts, however, we inhabit a markedly different world than Martial’s when it comes to building a library. I’ve got about 3,000 books in my personal collection, and I know people with far more. But even humble libraries are usually far larger than the typical collection housed in ancient homes—if such a “typical” collection existed at all.

We take our abundance for granted, but it’s the result of conditions that didn’t and couldn’t have existed in the ancient world:

industrial printing,

computer-assisted writing and editing,

global supply chains, and

a vast commercial publishing industry.

There were no equivalents to Barnes and Noble or Amazon back when, nor publishers like Penguin and Hachette. When Martial was busy scribbling gift guides, every single book he recommended had to be inscribed by hand one at a time. And yet people did build libraries, sometimes big ones. How did they do it?

In his book, Inside Roman Libraries, classicist George W. Houston identifies about a dozen different methods by which ancient Romans assembled their collections. I cover several of these in The Idea Machine to show just how much the ancient world differed from today, but I thought it would be fun to share some of those here.

I’ve collapsed and combined a few of Houston’s categories into six ways to build your personal library should you strangely awaken tomorrow in the world of, say, Martial, Menander, and Cicero. Buckle up.

1. Copy It Yourself

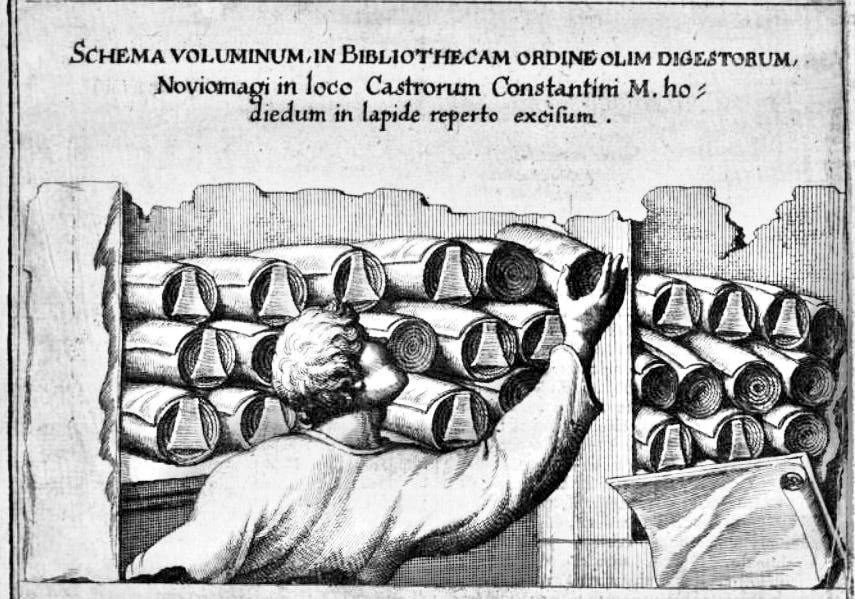

Back when Amazon referred to a tribe of deadly women who lived by the Black Sea, the simplest way of acquiring new books was to make a copy from a copy—yourself. You might borrow the exemplar from a friend or one of the public libraries, spread out a roll of papyrus, and start scribbling. This hardly strikes us as simple today; copying manuscripts was and remains tedious, time-consuming, and difficult. But what else could you do if you didn’t have the means to hire out the job?

Some preferred doing the work themselves to ensure they got accurate copies. In his treatise On the Avoidance of Grief, the physician Galen mentions copying books he consulted in various imperial libraries, referring to “the writings of the ancients that I had copied by my own hand.” Galen could have afforded outsourcing the work but wanted to guarantee clean copies.

Galen’s statement points to the primary drawback of copying books yourself besides the time required and tedium endured: The average literate person didn’t have the skills possessed by a trained scribe, as the final work would undoubtedly show. The Roman orator Libanius preferred having his assistant handle writing because, he admitted, his assistant’s hand was neater than his own. (You should see my chicken scratch.)

People who most commonly resorted to copying their own books? Students, who then as now were always short on cash. Imagine having to scribble out your own Aeneid! For the wealthy—and they were usually the only people who wanted to build substantial book collections in the first place—copying manuscripts was a chore you delegated, usually to a slave.

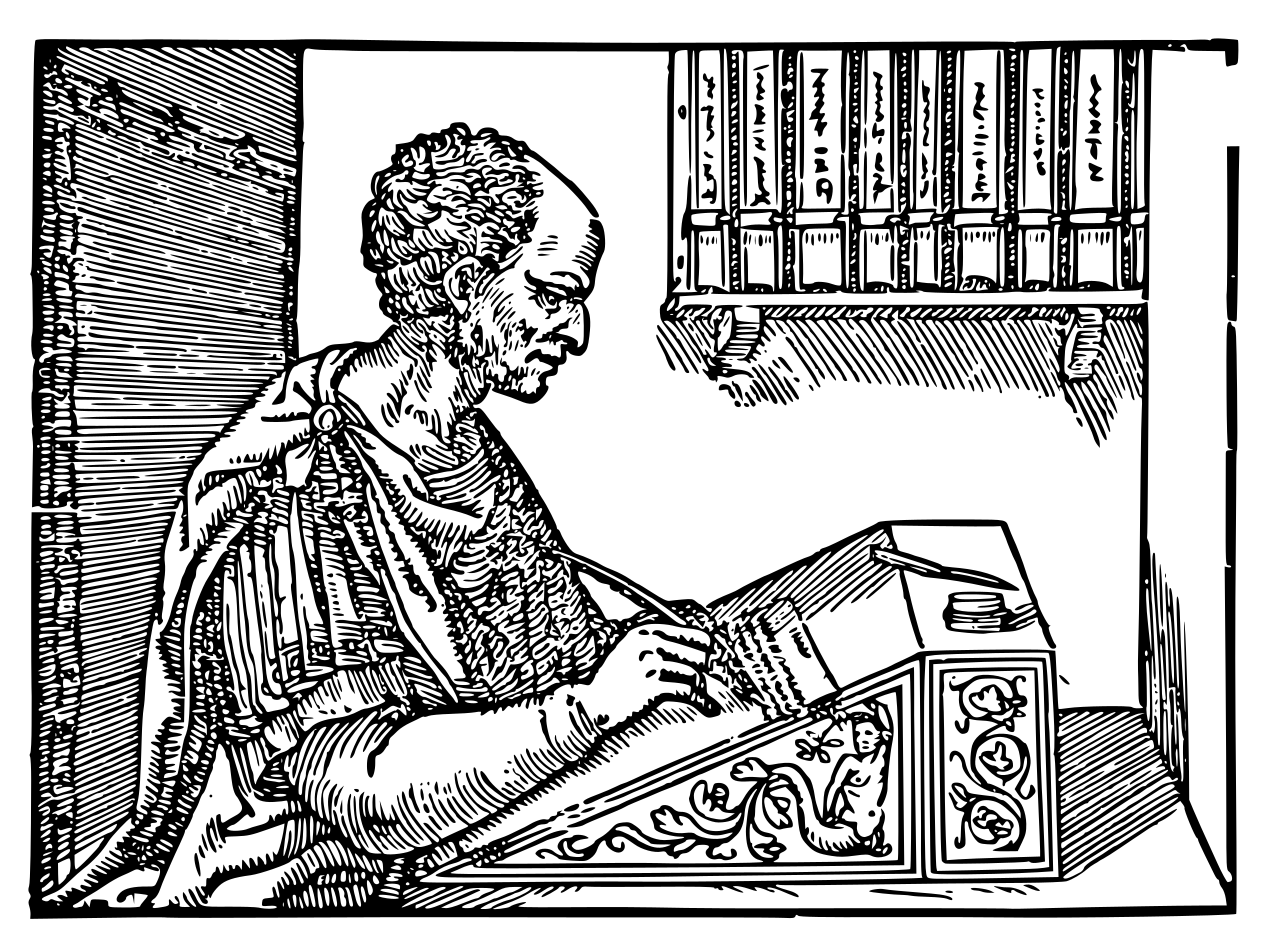

2. Have a Slave Do It

To accompany his tony villa, a wealthy Roman would have owned a household staff. Along with cooks and others, he might own a professionally trained scribe or two. Enslaved scribes were so common in the Roman world that historian Rex Winsbury refers to them as the “infrastructure” of the book trade.

Cicero’s friend, the book dealer Atticus, owned several. Cicero did too at various points in his life—but not always. In 57 BCE after returning from exile, he had no slaves on hand when rebuilding his library; Atticus loaned him some of his men. By 54, Cicero still hadn’t acquired the help he needed because he was reduced to scouring the book market for copies (more on that in a moment) and complained the available texts were riddled with errors (more on that too). If he possessed his own slave, he could have ensured the quality met his expectations.

Even without professionally trained scribes, a person might have a literate slave in their household copy a work if they were willing to live with a subpar product. Houston mentions a one extant example from the Leuven Database of Ancient Books. “Four different scribes were at work in the making of this copy [of Aristotle’s Constitution of Athens],” he says, noting,

all of them [were] inexpert. One of the four seems to have been the most important and may have supervised the work of the others; he corrected errors and filled in gaps left by the other three. . . . The variable quality of the copying shows that the copy was not made by professional scribes, even though there was a clear desire for an accurate text.

But whether you copy it yourself or have a slave do it, every copy needed an exemplar, an original to duplicate. Where could you get those?

3. Borrow a Copy to Make a Copy

Friends and libraries, as mentioned, were sources of exemplars. Ancient book lovers and institutions sometimes made their books available for others to read and copy, though loaning a book always presented the risk the person might sit on the volume too long—or never return it at all.

Cicero’s letters are full of examples of borrowing books for the sake of copying them. “I have received the books from Vibius,” he says in one letter; “he [that is, Alexander of Ephesus] is a wretched poet, and indeed has nothing in him; still he is of some use to me. I am going to copy the work out and send it back.” Cicero repeatedly borrowed books from Atticus. As Houston points out, he also borrowed from his brother Quintus, from Sextus Fadius, and from Marcus Lucullus.

Houston mentions other examples as well, such as when Marcus Aurelius (before becoming emperor) lent a copy of Roman poet Ennius to his teacher. The recipient, Fronto, then had a scribe make a fresh copy for his own collection. This sort of sourcing for exemplars was easier in Rome itself; the further afield one lived, however, the harder it was to find works to copy, and scholars and others wrote letters fishing for copies of whatever they could get.

The risk in loaning copies, of course, was that someone might not return the original. Does anyone ever return a borrowed book? Sidonius Apollinaris, a fifth-century Gallic aristocrat and bishop, acquired a copy of Mamertus Claudianus’s On the Nature of the Soul and loaned it to his friend Nymphidius “to examine and copy it and to make extracts.” Bad move. Nymphidius was slow to pass it back.

“It is high time for you to send the book back,” Sidonius complained in a letter. “If you liked it, you must have had enough of it by now; if you dislike it, more than enough. Whichever it be, you have now to clear your reputation.” A time-honored tactic: When in doubt, resort to shame.

4. Buy from a Dealer

If you didn’t copy a text yourself or have your slaves do it, you could turn to the commercial trade. You could, for instance, commission a scribe to make you a copy.1 You could also try your luck at the bookshops.

Bookshops existed in urban areas, and dealers both sold used books as well as made new copies for customers. Far from modern bookstores, which are jammed with inventory, they kept very little stock on hand. Mostly, they kept exemplars to be copied at the customers’ request. Martial directed readers to specific bookstalls where they could find his works. “Seek out Secundus,” he said in one epigram, describing the shop’s location. But acquiring books this way had its own challenges. The quality varied wildly and provenance was an issue.

As we’ve seen, Cicero complained the quality of books available in the shops was dicey. Errors were rife. The geographer Strabo complained of the same problem. “Some booksellers employ shoddy scribes and fail to compare copies,” he wrote, meaning they didn’t compare manuscripts against one another to correct for errors.

“Careful buyers might,” as Houston points out, “seek professional advice.” He mentions the case of a buyer who brought a textual expert with him to the bookstalls to examine the copies for sale. And then there was the question of whether the book was legitimately by the author in question; sometimes dealers (and authors) passed off bogus work. Without professional help, how could an unsuspecting buyer possibly tell?

If you were really looking to expand your library, you might consider buying a whole collection from someone else if it became available—usually as part of an estate sale. Plato grew his library this way, as did Aristotle. Same with Cicero.

It’s actually because of transfers like this that we owe our access to the works of Aristotle in the first place. Apellicon of Teos, a prominent book collector in Athens, bought the libraries of Aristotle and Theophrastus from the descendants of Neleus of Scepsis, who had inherited them from Theophrastus after Aristotle left Athens. Of course, that’s only half the story; we’ll come back to it bellow.

5. Inheritance and Bequest

Like Neleus, readers might inherit books as part of a bequest. Pliny the Younger, for instance, received 160 volumes of notes from his uncle and probably the rest of his collection as well. In fact, it was facing entries for “books” in wills and bequests that forced Roman lawyers to define the term in the first place. “When books are bequeathed,” said one jurist, “not merely rolls of papyrus, but also any kind of writing which is contained in anything, is understood.”

The library of Servius Claudius found its way to Cicero under such circumstances. Cicero wanted Atticus’s help in getting Servius’s books from point A to point B: “Now, as you love me, as you know I love you, stir up all your friends, clients, guests, freedmen, nay even your slaves, to see that not a leaf is lost. For I have urgent necessity for the Greek works, which I suspect, and the Latin books, which I am sure, he left.”

Following up, he added, “This gift depends on your kind services. As you love me, see that they are preserved and brought to me. You could do me no greater favour: and I should like the Latin books kept as well as the Greek. I shall count them a present from yourself.” An influx of books like this into one’s library was a windfall and didn’t happen often. Yes, your friend or uncle died. Sad. But look at all the new books! Yeah!

6. War Booty and Confiscation

Sometimes libraries were taken as war booty or seized as legal punishment, their contents suddenly available for acquisition by whoever possessed proximity to power. When he sacked Athens in 86 BCE, the Roman general Sulla captured the library of Apellicon of Teos—including all those books by Aristotle—and hauled them back to Rome as war booty. In fact, it’s to Sulla’s capture that we partially owe the spread of Aristotle’s ideas, not to mention those of other Greek philosophers, in the Roman world.

After the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, Mark Antony added public intellectual Marcus Terentius Varro to his enemies list. Officials confiscated Varro’s property, including his massive library with some 490 volumes he had authored himself. “We cannot be sure what happened to Varro’s manuscripts,” says Houston, “but it seems very likely that some or all of them were seized by Mark Antony, passed on Antony’s death to his wife Octavia, and were given by her to the library she helped found in the Portico of Octavia.”

Political and criminal trials often resulted in the seizure of the offender’s property and estate. In the case of wealthy and prominent citizens, that would have likely included books, sometimes large collections. Those books would have been sold with the proceeds divvied up between the prosecutor and the government—unless officials, including the emperor, kept the books for themselves, which seems to have happened. In fact, Houston says that may help explain the growth in imperial libraries:

If we assume that emperors did retain at least some of the manuscripts so confiscated, that would help to explain the appearance, every generation or so, of new library buildings in Rome: they would be needed to house the book rolls that had accumulated over the years, in part through gifts and the like, and in part through the confiscation of book rolls that had previously formed important private collections.

A Vastly Different World

It’s safe to say there’s nothing scalable about most of these methods of building a library. Confiscation and war booty, for instance, don’t increase the overall number of books but merely transfer them from one possessor to another. At the end of the day, the only way to get more books was to have them reproduced—one hard-won handwritten copy at a time.

Given our state of relative literary abundance today, it’s hard to fathom the level of book scarcity endured in the ancient world. Despite the remarkable achievements of the classical world, viewed from today’s vantage point, what stands out is how few books there were and how difficult it was to raise a collection yourself. Building a respectable private collection required wealth, connections, determination, some hustle, and loads of time.

Whatever the size of our personal libraries, every book in our homes today represents an act of acquisition that would have seemed miraculous to Cicero—a man who, for all his wealth and connections, sometimes couldn’t even locate a decent copy of a book he wanted.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

And check out my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, one of Big Think’s favorite books in 2025.

“I was left,” says Big Think editor Kevin Dickinson, “with a deeper appreciation for living at a time when books and all they have to offer have become so widespread.” Apropos given the post above.

Even trained scribes could struggle with their penmanship. Writing in the fourth century, Basil the Great admonished a scribe about his handwriting. “Make your strokes perfect,” he said, “and punctuate your passages to match them. For by a slight error a great saying has failed of its purpose. . . .” In another letter he chastised a calligrapher for shoddy writing:

Write straight and keep straightly to your lines; and let the hand neither mount upwards nor slide downhill. Do not force the pen to travel slantwise, like the Crab in Aesop; but proceed straight ahead. . . . For that which is slantwise is unbecoming, but that which is straight is a joy to those who see it, not permitting the eyes of those who read to bob up and down. . . . Write straight and do not confuse our mind by your oblique and slanting writing.

George Houston was a professor of mine and can be described by the Latin adjective probus, which means good, worthy, excellent, upright, and honest. Congratulations to him on the book and to you for discovering it and making use of it.

Even after the invention of print, books were still relatively rare and expensive, and their weight made it difficult to transport for those going on long journeys. I knew an elderly man who left most of his library behind in the UK when he moved to Canada, among them a complete set of hardcover Dickens. Laura Ingalls Wilder, in her novelized story of her childhood, talks about the few books her family had on their travels: the Bible, a book about wild animals, school readers, and a single novel which Ma read so often to Pa that Laura, reluctant to go to school, had the opening lines memorized and tried to convince Ma she could read by quoting them. In my teens, before the invention of the ereader, I used to try to decide which books I absolutely must have if I was going to travel the world.