That Hideous Farce and Other Offenses

Bookish Diversions: Charles Portis, C.S. Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Shirley Jackson, Our Scary Past, More

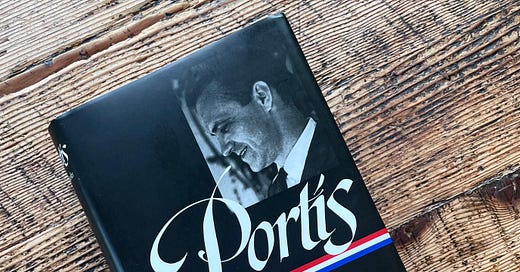

¶ True laughs. True Grit author Charles Portis and I share a birthday. I discovered this when thumbing through the recently published Library of America edition of his collected works. One thing I’d known long before? We also share a sense of humor. I discovered that while reading his novels.

I was aware of Portis since my late teens. I then worked at a used bookstore in Roseville, California, and shelved more copies of True Grit than seemed reasonable. I enjoyed watching westerns, not reading them. It was years later before I ever picked it up. Pity.

Several years ago now I bumped into The Dog of the South, a 1979 road-trip novel about a jilted husband, Ray Midge, traveling through Central America in search of his wife, her boyfriend, and his Ford Torino the absconding pair stole in their southerly flight. Everything about the book makes me laugh—the characters, the storyline, the language, and especially Portis’s wry, understated sense of the absurd.

The absurd shows up in all his books. It breaks the dial in Masters of Atlantis, the 1985 tale of gullible man who naively starts a cult, an esoteric blend of Freemasonry, Scientology, and Pythagoreanism. Possibly Portis’s least-popular novel, Masters of Atlantis now claims a cult following of its own among Hollywood comedy writers.

UFO spotters play a role in his next novel, 1991’s Gringos, as do hippies eagerly awaiting the eschaton. “Anything I set out to do degenerates pretty quickly into farce,” admitted Portis. Said Justin Taylor, writing at The Point,

The hallmark of Portis’s work is farce delivered with a straight face in successions of tightly choreographed set pieces, splitting the difference between the picaresque and the grotesque. . . . But one should not mistake lightness for slightness. Portis is a comedian of the highest order, but he is finally—as all comedians must be—a moral philosopher, because comedy, like prophecy, is always grounded in a critique of the world as it is based on a vision of the world as it ought to be.

While outlandish, Portis’s novels are utterly believable. “Although his novels have the fun of farce,” said Casey Cep, “part of what’s so charming about them is their relentless plausibility.“ That’s because Portis was a close observer of humanity and kept good notes. Everything—even the most bizarre character or event—is grounded in reality, a key ingredient of his humor.

None of Portis’s other novels achieved the fame of True Grit, which came out in 1968, edited incidentally by the recently departed Robert Gottlieb. It’s a curious fact: it’s the least like the rest of his books, and yet it overshadowed them all. Of course, it deserves every bit of its fame. I finally got around to reading it, and there’s a good reason I shelved so many copies at my little used bookstore; Mattie Ross remains one of the great American characters, and the book sold like crazy. It’s brilliant—and also funny.

If you’re up for a laugh and enjoy a good road trip, the rest of Portis’s novels might hold your ticket.

¶ That hideous farce. It’s fascinating to find our present moments foreshadowed in old books. Portis’s Masters of Atlantis amusingly anticipates the QAnon conspiracy craze, as Brian Doyle noted in Slate, and with everyone’s attentions glued on UFO news his Gringos feels newly relevant as well.

So, says New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, does C. S. Lewis’s 1945 sci-fi novel, That Hideous Strength. The story, in Douthat’s words, “boldly operate[s] in the risky zone between the sublime and the ridiculous.” Lewis never dealt in outright farce, but That Hideous Strength contains elements of it. Lewis

introduces a near-future Britain falling under the sway of a scientistic technocracy, the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments (N.I.C.E.), which looks like the World State from Huxley’s “Brave New World” in embryo. But as one of the characters is drawn closer to N.I.C.E.’s inner ring, he discovers that the most powerful technocrats are supernaturalists, endeavoring to raise the dead, to contact dark supernatural entities and even to revive a slumbering Merlin to aid them in their plans.

If naming a nefarious bureaucracy N.I.C.E. doesn’t amuse, what could? Recently, says Douthat, this fictional farce has taken on an air of plausibility.

The idea that technological ambition and occult magic can have a closer-than-expected relationship feels quite relevant to the strange era we’ve entered recently—where Silicon Valley rationalists are turning “postrationalist,” where hallucinogen-mediated spiritual experiences are being touted as self-care for the cognoscenti, where U.F.O. sightings and alien encounters are back on the cultural menu, where people talk about innovations in A.I. the way they might talk about a golem or a djinn.

The idea that deep in the core of, say, some important digital-age enterprise there might be a group of people trying to commune with the spirit world doesn’t seem particularly fanciful at this point.

To read the news is to realize reality sometimes is the farce, and satirists have the toughest job of all: somehow staying ahead of the curve.

¶ Treating the past like a scary place. The past speaks to the present, and sometimes we don’t like what it says. That’s true for a variety of reasons. When books reflect unfashionable ideas and express them in words we wouldn’t choose, we try to ban, edit, or flag them. Sometimes those ideas and words are offensive, other times merely outmoded. Either way, we feel duty-bound to fix the words and opinions of people who aren’t around to argue the case.

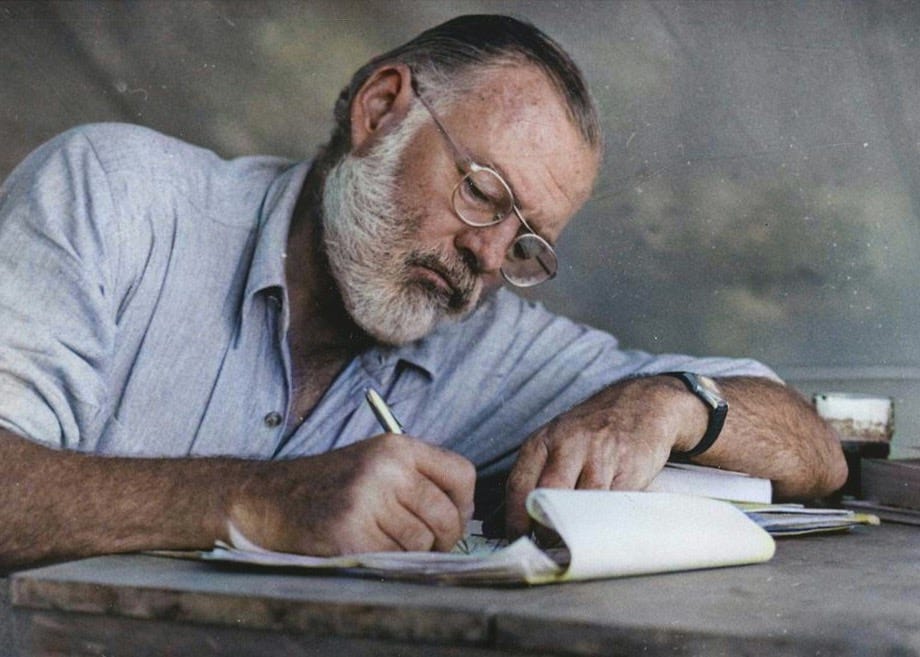

We’ve seen this with Roald Dahl, Ian Flemming, and Agatha Christie, whose works have been rectified by sensitivity editors. Now we’re seeing it with authors such as Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf, both of whose books are being rereleased with trigger warnings. E.g.,

This book was published in 1927 and reflects the attitudes of its time. The publisher’s decision to present it as it was originally published is not intended as an endorsement of cultural representations or language contained herein.

At least they’re not “correcting” the texts. But doesn’t this assume the worst about readers, that we’re both ignorant and fragile? Evidently, we’re unaware that people haven’t always thought as we do at this particular moment and require warnings lest we be surprised and undone by what we discover. “It’s indeed bizarre to treat the past as a scary place,” says Pace University professor Mark Hussey.

Hemingway biographer Richard Bradford was more blunt:

Scrutinize any novel or poem written at any time, and search for a passage that could create unease for persons who are obsessed with themselves, and you’ll find one. And then every publication will need to carry a warning like this, the verbal equivalent of photos of cancer ridden lungs which now decorate cigarette packets. Publishers and the literary establishment as a whole now seem to be informed by a blend of stupidity and bullying regarding what readers should be allowed to think.

¶ Don’t get too comfortable. Sometimes authors intend to discomfit. That was Shirley Jackson’s aim with her 1948 short story, “The Lottery.” Jackson’s biographer Ruth Franklin summarizes the story, including a spoiler:

On a warm, sunny June morning, village residents gather in the tranquil main square. They’ve assembled to conduct an ancient ritual, the meaning of which has been lost to time. One by one, they draw slips of paper from an old wooden box. . . . The person who draws a slip with a black dot is stoned by all of his or her neighbors.

Stephen King read the story in high school. “My first reaction,” he said: “Shock.” King’s reaction has been the norm for the last seventy-five years. And that was the point.

“The story went viral, in the way a short story could back then,” says Franklin. “Couples read it together and debated what it meant. . . . Readers called the story ‘outrageous,’ ‘gruesome’ and ‘utterly pointless’; some canceled their subscriptions.” Many assumed a publication error resulted in the final paragraph being omitted. Surely, the story didn’t end like that?!

But it did. And that ending forced readers to grapple with the morality of what they read in a way that heightened moral engagement, treating it like a parable that required interpretation, something unnecessary when the author shortcuts that effort and serves up a tidy, satisfying conclusion. “Great writing can entertain, enlighten and even empower,” says Franklin, “but one of its greatest gifts to us is its ability to unsettle, prodding us to search for our own moral in the story.”

¶ ‘We’re all grown-ups here.’ The question of portraying objectionable behavior in art came up during Tom Hanks’s recent tour for his debut novel, The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece. “I’m of the opinion that we’re all grown-ups here. Let’s have faith in our own sensibilities as opposed to having somebody decide what we may or may not be offended by,” said Hanks. “Let me decide what I am offended by and what I’m not offended by. I would be against reading any book from any era that says ‘abridged due to modern sensitivities’.”

¶ Whew! Incidentally, Library of America felt no need to edit, abridge, or provide trigger warnings for its Charles Portis collection, despite some objectionable material of its time. They just tossed readers like me into the deep end and hoped we could make it out alive. Amazingly, after rereading these funny, farcical novels over the last couple of weeks, I survived. I’m okay.

I live to read another day.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

You don't see That Hideous Strength mentioned very much, but it does have a resonance now. I used to teach that one in an Arthurian legend class. Lots of echoes with the long-surviving Arthurian tradition. It's the last of the "Space Trilogy" (Out of the Silent Planet & Perelandra being the first two), and the bad guys get their comeuppance in the end. As you'd expect, Lewis mixes up Christian and medieval stories as he built the story.

Great quote from Tom Hanks. Makes me feel that there is some reason somewhere.

First off, thank you for the recommendation. I ghost for a prominent television and radio pastor, so I spend my office hours pouring over commentaries and steeped in Greek and Hebrew. Y'allogy is a fun outlet for me, giving me a chance to speak (or at least write) in my native tongue—Texan.

To the point of your post, however: I appreciated your take on Portis. Though as an Arkansan he skewered my Texas sensibilities, True Grit remains a favorite for its simplicity of plot, complexity of character, and stripped down wit. The dialogue is filed to an edge sharper than an Arkansas toothpick, just as good country folk in the 19th century spoke. As a practitioner of dialogue, he ranks up there with two other masters I admire: Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy.

I also appreciated the quote from Bradford, especially the use of the phrase, "stupidity and bullying." His comment reminded me of something Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft, who in his preface to his commentary on Pascal's Pensées, Christianity for Modern Pagans, said in a footnote, no doubt because an editor redlined his text. Kreeft wrote, "Note on 'sexist' language: Those who insist on changing the centuries-old convention by which 'he' is shorthand for 'he or she' are invited to pay their dues to the newly neutered grammar god and add a 'she' to each 'he' in the following sentence, then read it aloud. If he (or she) does not have a tin ear for language, he (or she) will change his (or her) mind about his (or her) linguistic 'improvements,' I (or we) think."

The book was published with the universal "he."

Blessings.