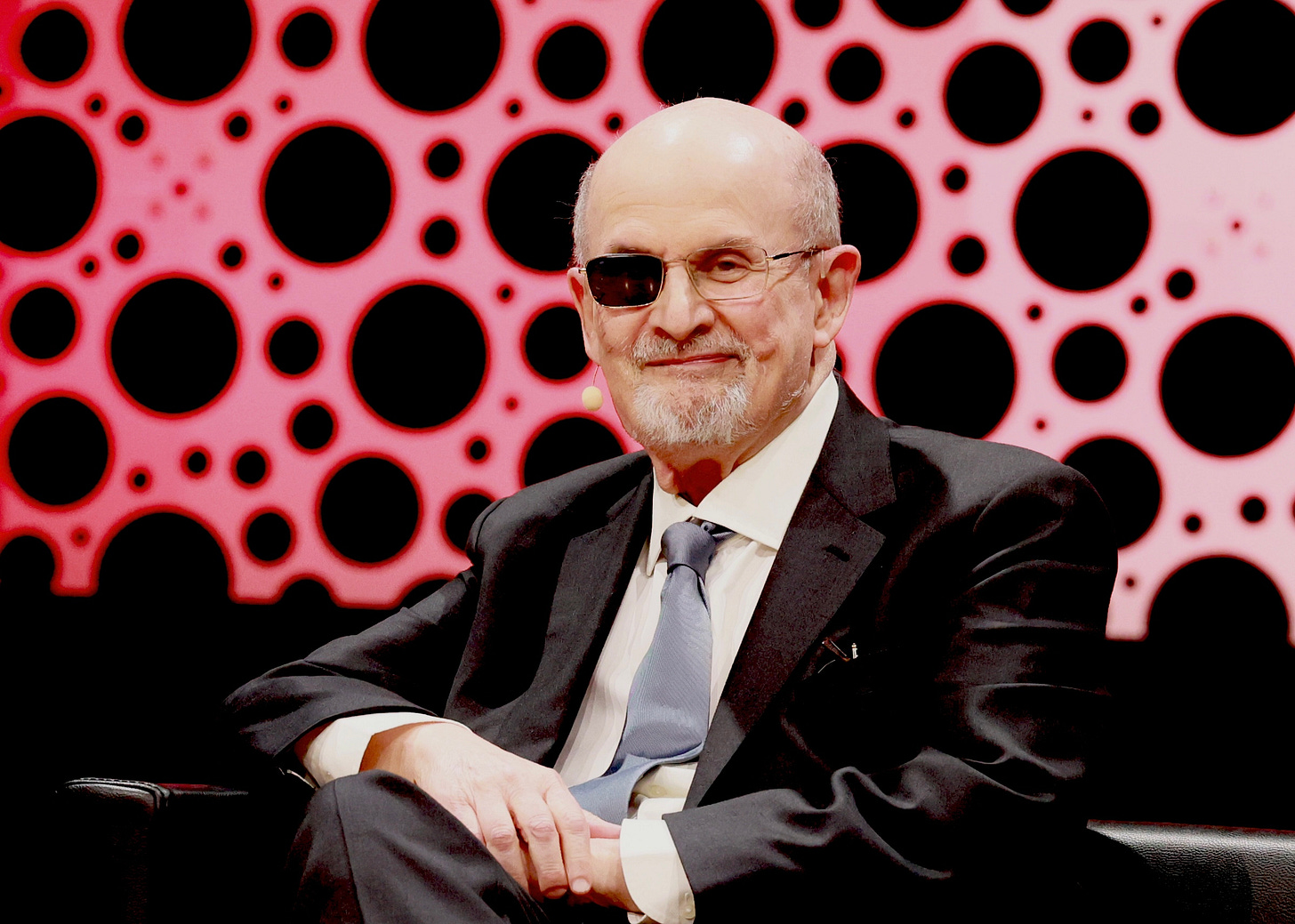

Salman Rushdie Writes Back

Love and Openness Trump Hate and Bigotry. Reviewing ‘Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder’

When novelist Salman Rushdie appeared August 12, 2022, in upstate New York at the Chautauqua Institution, he intended to speak on the subject of safety for writers and other public voices. He was already an object lesson. After Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa in 1989 against the writer for The Satanic Verses, Rushdie went into hiding.

Several people connected to the novel’s publication were either killed or injured in subsequent attacks—including, most recently, Rushdie himself. As Rushdie rose in the amphitheater to speak, a man darted from the crowd to the stage and knifed the author fourteen times.

The would-be assassin failed. Miraculously, Rushdie is still with us. And thankfully, he’s written about the horrendous experience in his new memoir, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder. While recovering from his injuries, which blinded his right eye and nearly took the use of his hand, Rushdie tried writing another novel. He couldn’t, not until he’d closed the chapter on his attack.

Knife offers an intimate portrait of a man on the mend, physically, emotionally, psychologically, maybe even spiritually, though Rushdie remains a serious atheist. He takes readers into the hospital room when he was unable to communicate except by wiggling his toes; shares how the love of his wife, poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, enabled him to recover; details his eerie premonition of the attack; stages an imaginary interview with his attacker; and finally returns to the scene of the crime for closure.

Love and Death

Rushdie divides the book in two, which is perversely apt as the knife divided his past from his future, the reality before the attack from the reality after. Part One, “The Angel of Death,” refers to his attempted assassin, whom he refuses to name in the book. Part Two, “The Angel of Life,” refers to his wife. Eliza forms the beatific center of the book, just as she appears to anchor Rushdie’s life.

Among the sweeter moments in the book, Rushdie takes us into the early days of their relationship when, while hoping to impress her, he walks right into a glass door, nearly knocks himself unconscious, and falls to the floor. “There’s a P.G. Wodehouse story called ‘The Heart of a Goof.’ That would be a good title for this episode too,” he says.

While trying to save face—not easy since his nose was bleeding—Rushdie retreats to a cab. They’d only just met, but Eliza joins him and never looks back. But then there he is several years later, now collapsed on the stage, bleeding from entirely different wounds, all those gashes and punctures, draining his very existence.

“At first I thought I’d just been hit by someone who really packed a punch,” he says.

Now I know there was a knife in that fist. Blood began to pour out of my neck. I became aware, as I fell, of liquid splashing onto my shirt. . . . He was just stabbing wildly, stabbing and slashing, the knife flailing at me as if it had a life of its own, and I was falling backward, away from him, as he attacked; my left shoulder hit the ground hard as I fell. . . . I remember lying on the floor watching the pool of my blood spreading outward from my body. That’s a lot of blood, I thought. And then I thought, I’m dying.

Dying, yes. But actions underway can be stymied and thwarted. It took twenty-seven seconds but attendees, including two security guards, stopped the attacker. Staving off death itself proved more touch and go, but doctors pulled Rushdie back from the brink.

Not that it looked that way, not at first. Rushdie went to Chautauqua alone. As surgeons raced to close the wounds on his face and torso, Eliza raced to the hospital, sure her husband had died. But he hadn’t. His injuries took eight hours for surgeons to repair, but he came through it. And Eliza was there when he woke.

The Recovery

Rushdie recounts the challenges of rehab and recovery. His eye had been stabbed, permanently damaged; his tongue cut; his liver and intestines punctured; the nerves and tendons in his fingers severed. Rushdie nicknames his doctors, specialists recruited to address one or another of his damaged organs: Dr. Pain, Dr. Eye, Dr. Hand, Dr. Stabbings, Dr. Slash, Dr. Liver, Dr. Tongue, Dr. Staples. Healing would prove an uphill climb, but in time he bid them all goodbye.

While in rehab, Rushdie suffers violent dreams, not of the attack itself but vague and sketchy recapitulations. “In them an ‘I’ figure was being pursued or attacked by an enemy, usually armed with a spear or sword,” he says.

Sometimes the location was an arena, sometimes a cage, sometimes open countryside or a city street. But I was always in flight, always pursued, and very often I lost my footing and then I was rolling left and right on the ground, trying to avoid my enemy's downward thrusts. At these times I was also thrashing about in bed.

Eerily, as he explains, before the attack he suffered a dream like this as well. He was rolling on the ground in a Roman amphitheater dodging the downward thrusts of a gladiator’s spear. The dream unnerved him so much he didn’t want to attend the event. Alas, he stuffed his concern and went. His attacker was waiting for him.

Throughout the book Rushdie refers to him only as “the A.” “My Assailant, my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, and with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation,” he says, “I have found myself thinking of him, perhaps forgivably, as an Ass. However, for the purposes of this text, I will refer to him more decorously as ‘the A.’ What I call him in the privacy of my home is my business.” One assumes it’s much coarser.

Part of Rushdie’s recovery involves confronting him. But, fascinatingly, not in person, or even in real life. In a bizarre but captivating reminder of the power of free expression, Rushdie unburdens himself from traditional reportage and official accounts. Instead, the novelist gives us his own idea of the A., an interview with a fictionalized attacker.

Beware starting a fight with a novelist: The writer not only gets the last word, he fashions his words as he chooses.

Writing Back

After the attack, people asked Rushdie why he didn’t defend himself. He put up his hand but not much fight. He addresses the question in the book, but the simplest answer is that the writer’s weapons—whether defensive or offensive—are sentences, clauses, and words. That’s how Rushdie deals with his attacker and, by extension, all of his kind, the radical Islamists who have bedeviled him for decades.

In four fictitious exchanges he treats such subjects as the futility of fundamentalist belief, showing how radical expressions of Islam—taught by an imaginary yet very real “Imam Yutubi”—are internally flawed and historically nonsensical. This is not to say that Islam is wrong, only that Rushdie believes as much and establishes reasonable grounds for his doubts.

About none of this is Rushdie triumphalist or gloating. He lets his target be himself. And yet he allows the rest of us to see how Rushdie’s skepticism is, at least on its own terms, understandable and non-threatening, which is core to the message of the book: That neither thought nor its expression are crimes. Nor should they be met with violence but rather, if desired, with more thought and further expression.

But that’s not the only message of the book, nor the most profound. By turns humorous and humane, probing and revealing, Rushdie’s Knife reminds us, “We would not be who we are today without the calamities of our yesterdays.” Nor without the generosity and self-giving of those who love us. And so when Rushdie returns to the scene of the attack, Eliza is there by his side.

“I’m going with you,” she tells him. “This time I’m not letting you make that trip alone.”

There in the amphitheater one year, one month, and one week later they revisit the scene, Rushdie explaining where he stood, where the attacker rushed, where he fell. “I could see that it was hard for Eliza to be there, but also good,” he says. “We hugged each other, telling each other wordlessly that we were there for each other, that we had come through the nightmare and it was okay.”

And that is the most resonant message of the book, that openness and love ultimately overcome hatred and bigotry.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post:

I’d decided to skip yet another memoir of trauma but your review makes it shine, so I’ll revisit. Thanks.

“Beware starting a fight with a novelist: The writer not only gets the last word, he fashions his words as he chooses.”

Such a great line from an insightful review!