Bookish Diversions: Salman Rushdie’s Sin

Free Speech, Ideas Beyond Borders, the Passing of Frederick Buechner and Rodney Stark, Indie Publishing

¶ Robust ideas can tolerate robust debate.

The moment you declare a set of ideas to be immune from criticism, satire, derision, or contempt, freedom of thought becomes impossible.

—Salman Rushdie, 2005

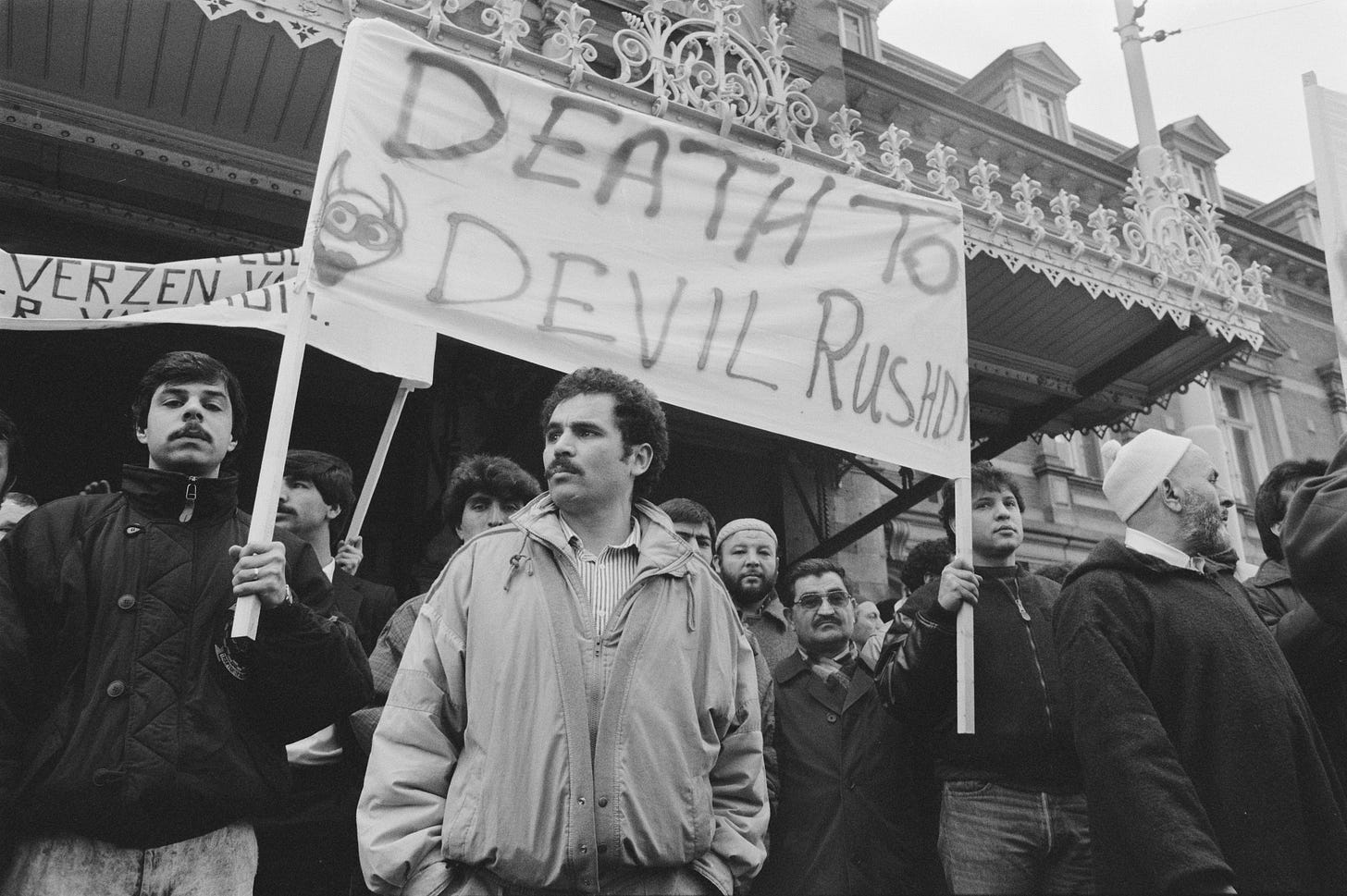

¶ I tried reading Salman Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses, about fifteen years ago. I was in my early thirties and vacuuming up fiction after a divorce. I didn’t enjoy it. I put it down after a few dozen pages and grabbed something else. Many others have similarly failed to enjoy Rushdie’s novel; one of them attacked and stabbed the author several times at a public gathering last week. Thank God, Rushdie survived and is recovering. The attack comes more than three decades after an order from Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran urged Muslims to kill the novelist for blasphemy. The Satanic Verses refers to an early and controversial Islamic tradition explained here by a professor of Islamic Thought and History at the University of Leiden. Following the attack, Agence France-Presse published a summary of the key events in the saga. Amazingly, a spokesperson for Iran said Rushdie brought the attack on himself: “We do not consider anyone other than himself [Rushdie] and his supporters worthy of . . . reproach and condemnation.” Rushdie’s sin is telling a story and not backing down because someone took offense. I’m all for kindness and deference; I’m also for authors having the freedom to speak their minds. Somewhere in that tension we can register disagreement—even disdain—for a writer and stay in our seats instead of stabbing him in the face. It’s not that hard; billions of us show similar restraint every day. As typically happens following violent overreactions to speech, Rushdie’s larger message and his offending book are only gaining renewed attention. Maybe I should give it another try.

¶ The value of words.

A poem cannot stop a bullet. A novel can’t defuse a bomb . . . But we are not helpless . . . We can sing the truth and name the liars.

—Salman Rushdie, 2022

¶ Meanwhile, the future of free speech remains uncertain. Said Booker-prize winning Nigerian novelist Ben Okri in response to the Rushdie attack:

We already live in a climate in which it is increasingly harder to express oneself freely. Now, this attack on Salman Rushdie, which many of us have feared for more than 30 years, has made creativity a matter of life and death. The internet has unleashed the monsters of trolling and hate speech. Death threats are issued to celebrities and to ordinary citizens expressing themselves on any number of issues.

We have become less tolerant of nuance and disagreement. The atmosphere is more toxic than it has ever been. Yet it cannot be said strongly enough that a society cannot survive without free speech. Democracy is built on the right to dissent, on the right for people to hold opposing positions. Our societies need freedom of expression to protect us from the worst atrocities that governments can visit on their citizens.

Here’s a balanced take on two historically separate kinds of free speech. The genius of modern liberal democracies was twisting those strands into one cord. Let’s not unravel it now. Alas, our track record here continues to worsen and concerns persist. See these excellent pieces by Adam Gopnik, Cathy Young, Margaret Atwood, and Kenan Malik, the last of whom literally wrote the book on the Rushdie saga. Malik closes, “We can only hope for Salman Rushdie’s recovery from his terrible attack. What we can insist on, however, is continuing to ‘say the unsayable,’ to question the boundaries imposed by both racists and religious bigots. Anything less would be a betrayal.”

¶ Ideas Beyond Borders. Two activists, Faisal Saeed Al Mutar and Melissa Chen, are working to expand the reach of ideas about science, free speech, and other liberal and enlightenment values. Back in 2017 the pair cofounded Ideas Beyond Borders, a nonprofit that translates books and articles on those topics for distribution in the Middle East and Central Asia, free of charge. Their response to the Rushdie attack?

A few hours after Rushdie was stabbed, I [Faisal] called our publishing partners in the Middle East and authorized the print and distribution of more than 5,000 copies of Rushdie’s books. I did this with the knowledge that it would put my life and my loved one’s lives in danger.

Read the rest, and make sure to watch this fascinating conversation between the two founders and Nick Gillespie, who sits on the board of Ideas Beyond Borders.

¶ Departures. I dedicated Bookish Diversions last week entirely to David McCullough, who passed away just days prior. Earlier this week award-winning novelist, memoirist, and essayist Frederick Buechner passed away at 96. Here is an obit in the New York Times, and here’s a worthwhile 1997 profile by Philip Yancey from the sadly defunct Books and Culture. I’d also like to note the passing of sociologist Rodney Stark, whose death in July escaped my attention. Stark’s talent involved applying his sociological toolkit to questions of religious history in books like The Rise of Christianity and Cities of God. Here’s something I wrote back in 2008 after reading Stark’s surprising book, The Victory of Reason:

“Calvinism is evidently connected with the commercial vocation,” writes Luigi Barzini in The Europeans. “It is not clear to an Italian [like the author], however, whether Calvinists, driven by their stern religious code, become the best merchants, or whether merchants become Calvinists because Calvinism is a superior guide for the successful conduct of business.”

It turns out that Barzini’s is an avoidable conundrum. Like the great Italian scribe, I’ve long been influenced by the concept of the Protestant Work Ethic—that the rigorous sects of the Reformation (namely the heirs of John Calvin) birthed capitalism. Then I read Rodney Stark’s The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success (Random House, 2005).

If Stark is correct, and he is convincing (which is almost the same thing, right?), the Protestant Ethic and its supposed creation of capitalism is a myth. Barzini should have started by looking in his native country. Stark shows that Italian Catholics were the first true capitalists, the merchants of such cities as Venice, Florence, Genoa, and Milan. In fact, he roots the entire flowering of Western economic, political, technical, and cultural dominance in the pre-Reformation church, showing how key technological and commercial advancements emerged from, of all places, European monasteries.

I was frankly astonished by some of the revelations in Stark’s book. . . . The Victory of Reason is a theological and historical reevaluation that shows the spirit of capitalism, even Western liberty, is not uniquely Protestant. It is inherent to Christianity more broadly construed, its doctrines, practices, and institutions.

Authors pass but books persist—at least some of them. Writes Eugene Vodolazkin in his novel, The Aviator, “It’s so strange: the person is already gone, but, yes, a book continues to live.” Faith can handle dissent, disagreement, and argument. I hope Buechner and Stark’s books, models of sturdy engagement, keep going for years to come.

¶ Long live indie presses. Publishing quality books, says Micah Mattix, “has always required a team.” True, there are self-publishing success stories. But they’re rare.

Few writers have the eye for design, the editor’s sense of obligation to the audience, the grammarian’s attention to detail, the administrator’s love of all things administrative and the salesman’s bravado needed to bring out books of quality. Writers may be able to do one or two of these things well, but never all.

So, what if you have an idea for a book that a major publisher doesn’t get or see potential in? Indie presses provide publishing teams for niche books, and usually elevate them far higher than whatever altitude an author might achieve on their own. Strive, for instance, is a publisher focusing on black voices. Ancient Faith (which also produces my nichey “Bad” Books of the Bible podcast) focuses on Eastern Orthodox books. Mattix highlights several small publishers who warrant attention for the unique books they birth. His list includes the always-fascinating Slant Books, which publishes an impressive array of fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. I’m personally mixed on big-publishing-house-merger news. To employ Reason magazine’s tagline, I’m for both free minds and free markets. It’s nonetheless worth considering the special value independent publishing brings to authors and readers.

¶ In closing,

Beware of dogmas backed by faith; Steer clear of conflicts to the death; Keep going; never stop; sit tight; Read something luminous at night.

—Edmund Wilson, Night Thoughts

¶ Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

¶ If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-ten quotes about books in your welcome email. They won’t improve your looks, but they’ll make you sound more interesting at parties. Thanks, again!