On the Go: The Age-Old Human Adventure of Migration

Crossing Borders. Reviewing Sam Miller’s ‘Migrants’ and James Crawford’s ‘The Edge of the Plain’

Humans are known as Homo sapiens—Latin for wise man. But we could just as easily go by Homo vagans or Homo migrans—wandering or migrant. While there’s heaps of controversy today about migration, one fact is indisputable: People up and go. And we’ve done so as long as there have been people.

It’s there in our founding stories. Aeneas leaves Troy to found Rome. Abraham leaves Ur for Canaan, and his descendants boomerang back centuries later by way of Egypt during the Exodus.

Some of the earliest writing on record—clay tablets from Mesopotamia—contains details of migrants: nomads on the move, merchants arriving from the East, imported slaves, encroaching mountain peoples, and more.

The Greeks dotted the Mediterranean with settlements, and Alexander the Great chased the rising sun as far as India, leaving Hellenist outposts across the Near East. On the other side of the globe, Polynesians braved the 10 million square miles of the cartographical triangle of open sea named for them.

Even those who assumed they’d always been rooted where they first recognized their distinct identity as a people usually came from somewhere else. Out of Africa isn’t just the title of an Isak Dinesen novel.

As archeologists and anthropologists argue, the people we would eventually recognize as Indigenous Americans crossed the Bering Strait over ten thousand years ago and likely spread rapidly southward by way of boats along the food-rich coastlines. One group of people, the Yaghan, made it as far as the southernmost tip of Tierra del Fuego.

Sam Miller captures this rich and deep history of sojourn and wayfaring in his book Migrants: The Story of Us All. The book covers the ancient Phoenicians and Hebrews, Romans and Vandals, along with modern accounts of Zionists, Chinese immigrants, Bracero guest workers, and global refugees.

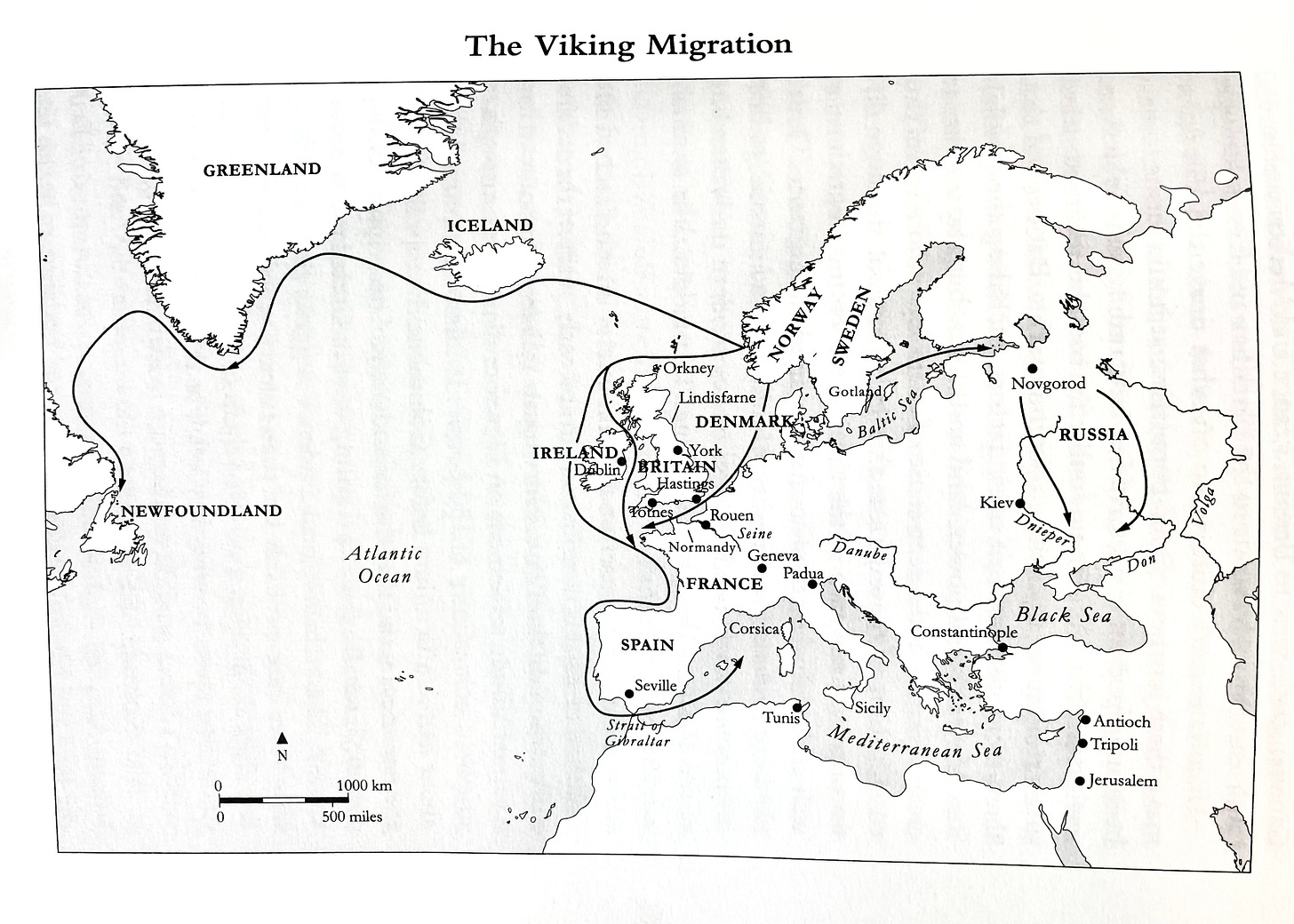

My maternal grandfather, whose parents emigrated several years before his birth, was proudly Swedish. The old Viking tales and history enthralled me as a teen. My Christian upbringing made it impossible to take their side against the Irish, Scottish, and English monks, of course. But I was impressed with their moxie and daring nonetheless, and I felt a twinge of pride knowing that was also me somehow.

Then my grandpa burst my bubble by telling me that the Danes, not the Swedes, mostly raided and settled Western Europe. My Viking forebears instead traveled east into Russia to trade. I was unimpressed. Only later did I discover what a feat that proved.

Navigating waterways and overland passages the Swedes made it all the way to Constantinople where they served the Byzantine emperor as members of his Varangian guard. They fought in Italy, Crete, Georgia, and Syria, and one graffitied his name, Halfdan, in runes in the upper gallery of Hagia Sophia.

“Back home in Sweden more than 20 memorials to those who were killed fighting for Byzantium have survived,” says Miller,

standing stones inscribed with the names of those who died far away, and just a few who returned from Constantinople as rich men. And on one of the stones, found on the Swedish island of Gotland, was the tersest of testaments to Viking wanderlust: just six words, the first two being the names of the travelers, Ormika and Ulfhvatr, the next four words, their destinations, Greece, Jerusalem, Iceland, Arabia.

Many stayed where they spread, none more permanently or significantly as the Rus, Vikings who established the domain that would eventually become Russia. From there, the ruling family of Rurik the Viking married into the monarchies of Europe. “Most of the modern royal families of Europe can trace their ancestry back to Rurik,” says Miller. Not too shabby for a bunch of vagabonds.

What emerges from Miller’s telling of such stories are the fundamental ways in which migrations have shaped human history all around the globe, effecting everything from culture and religion to politics, war, and more.

People hit road and waterway for all sorts of reasons, not least adventure, but many others besides: trade, refuge, destitution, and expulsion. Not everyone, for instance, came out of Africa willingly. The forcible deportation of millions of captive Africans, exiled to New World plantations and estates, forms an incomparably awful chapter of human migration.

“More than 12 million captives,” says Miller “were carried across the ocean over a period of about 350 years. At least a million newly enslaved people are thought to have died on the journey from their homes to the coast of Africa, and almost two million died as they crossed the Atlantic.”

Lest we think of this terrible episode as ancient history, Miller points out that just a hundred years ago novelist and lay anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston filmed a former slave, Cudjo Lewis, outside his home near Mobile, Alabama.

Many people born in slavery were still alive in the 1920s. Lewis was different; he was born free in West Africa, enslaved by the king of Dahomey, purchased, and illegally transported to America along with more than a hundred others. You can actually watch a bit of Hurston’s footage on YouTube and see Lewis crack an inviting smile.

Tragedy has and will always attend travel. But tragedy can also strike when people stay more or less put—when borders move even if people don’t. Migration forms part of James Crawford’s narrative, but his focus in The Edge of the Plain: How Borders Make and Break the World is how arbitrary lines in minds, on maps, and sometimes marked with stones can drastically change human experience.

Consider the Sámi, who clustered around Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia before there were Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, and Russians. While my ancestors were traipsing back and forth between Sweden and Asia, semi-nomadic Sámi ranged with reindeer herds throughout Scandinavia.

As kingdoms and later nations formed, the Sámi found themselves caught in between. The Norse king Óttar bragged while visiting Alfred the Great around AD 890 that he collected tribute from the Sámi. By the sixteenth century after Sweden broke away from Denmark, an official census noted the existence of 300 Sámi in Sweden stuck somehow paying taxes to Swedish, Danish, and Russian authorities. Only recently have Sámi received the standard rights and recognition of their Nordic neighbors.

Both Miller and Crawford are journalists, and both books contain first-person reportage, but The Edge of the Plain depends on it. Crawford follows a two-man team erecting stone markers for the original U.S.-Mexico border. He spends time in walled-off Palestine. He travels across the Alps, tracing Italy’s shifting mountain border. And he explores how disease and epidemics play into cross-border politics.

Crawford finally lands in Africa at the southern reach of the Sahara where the desert pushes its way into West Africa, devouring land that might otherwise sustain human communities. There he talks with Tabi Joda, a man who almost migrated away from his deforested homeland to Spain but chose at the last minute to stay. Why?

“I’m going to turn this dry land into a forest,” Joda said. He’s now an active participant in a movement to create a Great Green Wall of trees to hold back the encroaching Sahara.

There’s an irony in this verdant border, of course. Africa was carved up by European powers whose encroachments during the Scramble for Africa were far more extensive and destructive than the Sahara. There are more artificial borders in Africa than anywhere on earth, accounting for levels of discord and strife unlike anywhere else as well.

If its advocates are successful, the Great Green Wall will finally represent a border that brings West Africa together and provides a reason for its many residents, like Joda, to stay instead of go.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Fascinating!