Many People at Once: The Role of Literary Translators

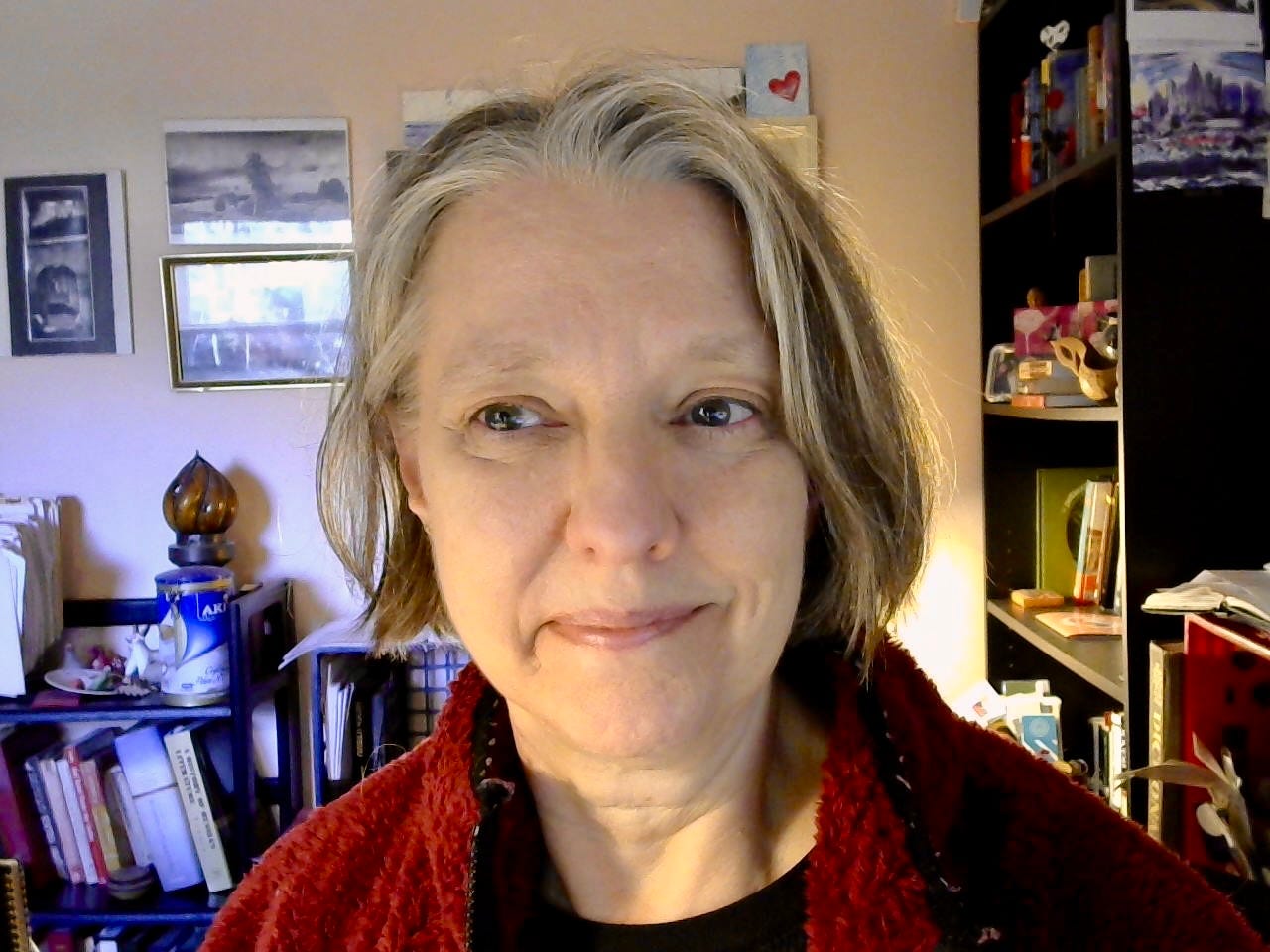

Translator Lisa C. Hayden Discusses the Challenges of Translation, the Role of Intuition, and Why She Never Recommends Specific Editions of Classic Works

One of my favorite living novelists is Eugene Vodolazkin. If he writes something, I’m reading it. But then again, I’ve never actually read Vodolazkin. Rather, I’ve read translations of Vodolazkin from Russian into English—mostly by award-winning literary translator Lisa C. Hayden. Thank God for Lisa!

She’s translated ten books from Russian to English, including Vodolazkin’s celebrated novel, Laurus; my personal favorite, The Aviator; and his newest, A History of the Island. Hayden’s translation of Laurus was a finalist for the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize in 2015 and won the Read Russia Prize for Best Translation of Contemporary Russian Literature in 2016. In 2020, her translation of Guzel Yakhina’s novel, Zuleikha, was shortlisted for the the EBRD Literature Prize, the Read Russia Prize, and the National Translation Award in Prose.

Having benefited from her work, I was confident we’d all benefit from her thoughts on literary translation—how its done, its challenges and rewards, why she never recommends specific translations of classic works, and more.

Miller: I think of translation as one of the greatest but sadly invisible roles in publishing. Without translation, we’d have no access to so many works that define our culture. Why is it so underrated?

Hayden: This is something I ask myself a lot. I think part of the reason is that some people misunderstand what translation is. It’s a literary art—rewriting a text in another language—not a clerical, typing task. “Lost in translation” isn’t doing anyone any favors either.

How did you get started in the work?

The long-story-short version is that back in the late 1990s I wanted to write my own fiction but lacked the patience to develop characters and plot lines. Translation gives me the fun part of writing—choosing and ordering words—and lets me use my Russian. I leave plots and character development to my authors. I learned a lot about technical aspects of writing fiction back in the noughties when I went to a few writing conferences and workshops. They were well worth the time and money.

What is your favorite part about the job?

The final two or three drafts, when what started out as a messy draft finally reads like a real book.

How do you choose your translation projects? What criteria do you use?

It’s primarily a question of intuition. This has been on my mind lately since I just finished reading an author’s manuscript. I read the whole thing and enjoyed it very much, but my primary goal was to get a feel for the language, to see if the book and I would be compatible. I didn’t analyze or fuss over anything; I just read. The book thoroughly captured my imagination and the language felt right, too. Fingers crossed!

“Translation is as much about interpretation as anything else. It’s a creative art. . . .”

—Lisa C. Hayden

What’s the most challenging part of the translation process for you—positive or negative?

Positive: finding the right words and ordering them properly. (Taking a shower often helps to resolve knotty problems.)

Negative: sitting still for my final reading! By that point I already know it reads like a real book. And by that point it’s very tedious to take one last look for errors.

When it comes to translation choices, there’s not always a “right” choice, just the choice that seems best. How does literary intuition play into your work?

I rely a lot on intuition. It particularly kicks in when I’m reading the manuscript out loud. I’m listening for lots of things but particularly want to feel that there’s an ease to the reading and a rhythm to the writing. I know when they feel right but rarely know how to explain why they feel right.

Lots of choices feel wrong until the very last draft—or even when I’m answering an editor’s queries. I’m doing that right now and, oh my, do I see lots of things to change in the manuscript! Thank goodness for thorough editors.

How about tough passages: What is the hardest passage you have ever translated and what made it so difficult?

The most difficult passages often involve arcane material or many layers of meaning. But every translation is difficult. That’s not because of poor writing but because so many elements need to work together in fiction. That means the translator is lots of people at once: writer, interpreter, psychologist, and sometimes, let’s say, a historian or a doctor.

Sometimes the most difficult part is to hold back—to, as I think of it, do no harm. Simpler is often better, particularly in a book like Laurus, where the syntax is basic, the sentences are short, and the words just flow. The complications there are the fun part, with the funnest being Vodolazkin’s use of archaic words. Retaining the simplicity of the rest of the text was important so the archaisms and the novel’s other unusual features could retain their power.

“The translator is lots of people at once: writer, interpreter, psychologist, and sometimes, let’s say, a historian or a doctor.”

—Lisa C. Hayden

You’ve now translated several of Eugene Vodolazkin’s novels. What’s it like working with him? And what’s it like working on several projects by the same author? Are there challenges in representing a larger body of translated work?

I’ll start with your last question. I think the biggest challenge is capturing the common threads, literary devices, and even vocabulary that the books share. Vodolazkin writes a lot about time, barbers who snip the air with their scissors, and пространство (prostranstvo), which I generally translate as “expanse.” Words that repeat are often hardest to deal with since the same word in English may not fit nicely each time the Russian word occurs.

Since I love working with my authors, the best part of translating multiple works is that I have additional opportunities to translate them. Working with Vodolazkin has always been a particular treat since we both value intuition so highly in our writing processes.

We’ve met in Moscow, New York, and St. Petersburg over the years and the very fact of having the opportunity to hear his voice and intonations, in person, helped me tremendously when I translated Laurus. Laurus was a particular joy to translate, thanks to elements like the archaic language and the mythical herbs. And, of course, Vodolazkin himself. He’s very generous.

As you alluded to above, Laurus plays with time and relies on a lot of anachronistic language. How did you handle that?

I wrote an essay about this for Lit Hub when the translation was published (you can see that here), so I’ll just say here that intuition and medieval Bible translations were my primary tools!

Do you ever have authors push back on some of your translation choices?

I wouldn’t say “push back” since they’ve always been very nice about things that were wrong or not quite right. Errors and oddities are inevitable, given that translation is as much about interpretation as anything else. It’s a creative art, and there’s only so far I can get into my authors’ minds, only so much I can unravel the internal logic of their texts.

A combination of intuition, careful reading, checking lots of dictionaries and other reference books in Russian and English, staring out the window, and talking with colleagues and my authors helps me sort things out.

I read a favorable review of one of your translations. “The writing,” the reviewer said, “comes across as extremely adept yet relaxed. Often, it can only be described as beautiful.” He compared that to another sort of work, where he said readers instantly get “the scent, if not outright stench, of translation.” For that sort of translation the Oxford English Dictionary offers us the word “translatese,” meaning something clunky and awkward. How can we—readers and translators alike—avoid that sort of thing?

I could talk about this topic for hours! There are varying schools of thought on how much a translator should domesticate or foreignize when translating. And of course translators and readers (not to mention editors!) have their own preferences on how much domestication and foreignization they want to see in a translation. I tend to like some of each but every book has its own demands.

This is a bit off-topic but I’ll mention it anyway. The question of taste is the big reason I never give specific answers when people ask me what translation of a classic to read. And I never know which one is “best”! I always suggest sampling the beginning of available translations. When I do this before making my own choices, I’m looking for the version of the book that feels like a good companion. I’ll be spending hours with it.

A good translation takes a lot of time and revision to read well. Lots of things go into it. Staring at something (or nothing) as I mentally riff on words. I also watch chipmunks and visit with our cats. Though reading out loud isn’t (always) quite as enjoyable as playing with the cats, it’s one of the best ways to ensure that a translation reads well.

To expand on what I said above, I’ll add that this reading helps me find and fix awkward wording, replace individual words that sound like they don’t belong, and gauge the rhythm of the text. English is pretty flexible but, as I realized while revising a story last week, one of my primary goals is to use that flexibility as much as I can while also (perhaps even more important) preventing myself from attempting to force English to do things it cannot or should not do.

The greatest pleasure of reading aloud is that I always do it in the middle of the process, when the text is (usually!) starting to read well. Those are some of my happiest moments with my books and stories. I usually read aloud again during editing, to be sure that all the changes, which likely come from two editors, sound right.

What’s one thing you wish the average reader understood about translation but doesn’t?

I’d love to see dislike of translations move away from blaming the translator for “losing” something. Languages differ. The very fact that a translation exists is a gain.

Alright, here’s a hand grenade: How can translators utilize AI in their work, and should they? What challenges or opportunities does AI pose?

I know very little about AI so don’t have a real answer to these questions other than to say that the fun and the challenges of translating fiction lie in the human thought, emotions, and feelings that go into writing the translation.

“The fun and the challenges of translating fiction lie in the human thought, emotions, and feelings that go into writing the translation.”

—Lisa C. Hayden

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

I don’t mean to be contrary, but I’ve had so many wonderfully memorable unplanned meals with colleagues and friends who are writers, translators, literary agents, editors, and publishers that I’d much rather stick with the random approach!

And so, since I’ve also had lots of unexpectedly wonderful (and, truth be told, unexpectedly odd but very interesting) meals with total strangers I met at book events, my choice would be to twist the question a bit by going to, say, the Frankfurt Book Fair and eating lunch with the three people standing behind me in line. Who knows what might happen?!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Knowing that what God did with languages at Babel was so thorough, I agree that translation is nearly impossible as a 'carrying across.' It has to be a creative process. Thanks, Lisa.

Best answer ever to your standard question of picking three people to have dinner with (or with whom to have dinner): go to a book event and have lunch with the three people in line behind you.