Called to the Good, True, and Beautiful

Talking Vocation with Karen Swallow Prior

I was delighted to have an excuse to talk with Karen Swallow Prior recently. Who wouldn’t? I’ve known Karen over a decade now. We first worked together on her book Fierce Convictions back in 2013. Her latest, You Have a Calling, joins a long list of others, including The Evangelical Imagination, On Reading Well, and Booked.

Known for her love of classic literature, Karen is the 2025–26 Karlson Scholar at Bethel Seminary, a senior fellow at the Trinity Forum, and a research fellow at Comment. Her guide to the classics series for B&H Publishing features such titles as Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Sense and Sensibility, Frankenstein, and The Scarlet Letter.

She writes for The Dispatch and the Religion News Service, and her writing has been featured in the New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Christianity Today, First Things, Vox, and other publications. She maintains her own newsletter here on Substack called, naturally, The Priory.

She lives with her husband on a 100-year-old homestead in central Virginia with dogs, chickens, and loads of books. In this conversation, we talk about vocation—the subject of You Have a Calling. I’ve interviewed Karen before; you can read that here.

I recently heard columnist George Will refer to writing as a “metabolic necessity.” A lot of writers feel similarly, whether they get paid much for the work or not. We simply don’t know how to be in the world without writing. Is that a calling—and how would we know?

The way I define calling in the book is that it’s something that comes from outside ourselves, whereas passion is something that comes from inside. It’s amazing when these two—calling and passion—completely coincide, but that doesn’t always (or even often) happen.

The way we are “wired” as individuals is part of both calling and passion. Some of us are made in such a way as to need to process the world and to create things in the world through writing, regardless of pay or applause. Others are “wired” in other ways. Will’s metaphor of “metabolic necessity” gets at this same idea.

“Metabolic necessity” isn’t necessarily a calling, but it can become one. In the case of writing, I think we know it’s a calling and not just an inner passion when our writing serves others in some way.

“The way we are ‘wired’ as individuals is part of both calling and passion.”

—Karen Swallow Prior

One of the most striking things about You Have a Calling is the idea that vocation is something we discover, discern, and sometimes even resist. Could you talk about that dynamic process?

Contrary to popular myths, callings are not always things we pursue; rather, they are often discoveries we make along the way, or even understandings we gain in looking back. For many of us within the context of our current, late modern, highly individualistic culture, that process starts with distinguishing between—as I’ve already mentioned—external calling and internal passion. We often assume they are the same, but they are not.

Discerning a call to do or be something in the world means paying more attention to the world outside ourselves so as to see how we might uniquely serve it. Now certainly, we need not and should not say “yes” to every need or every call. But we can better discern what to say “yes” to by better knowing both our community and ourselves. That’s really the key. In fact, the resistance to a call can come from not knowing our own strengths and abilities (listening to others can help us find those), and it can equally come from not accepting our limitations.

The idea of calling comes out of the Western Christian tradition. Is there a benefit in this concept for increasingly secular people like us? How do you think the language of calling helps us articulate that hunger for meaning?

Oh, I think that the concept of calling and even the term itself are both helpful for an increasingly secular society. There’s a reason there is right now so much discourse around work, work-life balance, and the meaning of work. Much of it is coming from the secular world, and there is a lot that the Christian understanding can and should offer to the conversation. Because human nature doesn’t change, even when our cultural context does, we know that the innate desire for meaning, purpose, and significance still exists even if not framed or understood in religious terms.

The doctrine of vocation articulated by the Protestant Reformers advanced the idea that there is no division between sacred and secular. That means that the Christian’s work outside the church is just as “spiritual” as work inside it. And it also means that those who aren’t Christians are still contributing to God’s design for the world, a design that calls for human beings to play a part in sustaining and stewarding creation.

“Because human nature doesn’t change, even when our cultural context does, we know that the innate desire for meaning, purpose, and significance still exists even if not framed or understood in religious terms.”

—Karen Swallow Prior

Good work feeds our souls just as it feeds and cares for our neighbors’ bodies. We were made to work, but like all good things, work can be exploited and misused, and when it is, it harms the soul as well as the body.

You explain that calling isn’t only about career. It can show up in family life, civic life, or even hobbies. Why do we so often collapse it into “job title” or “résumé” when it seems so much broader?

It’s a paradox that in erasing the distinction between secular callings and sacred ones, the Protestant Reformers also contributed, consequently, to the elevation of work itself to the point where it has become the most defining feature of life in the modern age.

Now, as I mention in the book, this also has become a particularly American characteristic—the thread that runs from the Puritan work ethic to the American Dream is a bright one. It’s certainly true that many of us find and fulfill some of our primary callings in our work life (I certainly do), but it’s crucial to recognize that we have other callings that are actually more important and that contribute significantly to the meaning we find in work. The roles we have in families, friendships, churches, and communities are callings, and each calling is meant to serve the others.

What about the risk—the danger?—of confusing calling with personal ambition or ego? How do you suggest we distinguish between a true calling and a self-serving pursuit?

This is a great question. Obviously, personal ambition and ego can infect anything we do. I find virtue ethics to be most helpful for such a question. Virtue ethics teaches that moderation of a quality is virtuous and both deficiency and excess are vices. To lack ambition is as much a vice as excessive ambition. Similarly, healthy self-regard is virtuous while both selfishness and self-effacement are vices.

Finding and maintaining proper balances in these things is seldom easy. But it’s actually what we are all called to do if we want to live wisely and well. Using the gifts and talents we have to serve the world through our callings requires enough ego to recognize we have the ability to do so and to do it well. And serving well requires a small enough ego to make room for the gifts and talents of others.

Your earlier book On Reading Well explores how literature forms virtue. Do you see a connection between cultivating virtue and being faithful to a calling?

Absolutely! As my answer to the previous question indicates, virtue is essential to finding and fulfilling one’s callings. In On Reading Well, I show how literature cultivates virtue and how virtue itself constitutes the good life. In this book, I’m exploring how the delicate dance between competing things—inner passion and external call, personal life and work demands, financial needs and creative pursuits—can draw us into our callings and more deeply into the good life.

“Literature cultivates virtue and . . . virtue itself constitutes the good life.”

—Karen Swallow Prior

You emphasize listening—to one’s conscience, to community, to circumstances. What are some practical ways a reader today might actually “hear” their calling amid the noise?

There is so much noise, isn’t there? As someone who is connected to many people and many voices in many contexts, I find this to be a particular challenge for me. I’ve definitely answered some wrong numbers! I don’t want to close off any voices that might be helpful in hearing my call, but I need to rely most on trusted ones. (And to be honest, my trust level these days is low.)

Practically speaking, I think you need to listen to the perspectives of those closest to you, those mid-distance from you, and fresh voices. I have one colleague I almost always go to for input on professional opportunities, for example. He has shown me, wisely, that I need not operate from a scarcity mindset which might be my natural default position. I have also invested heavily over many years in friendships and relationships that easily could have waned over time and distance, but have instead, because of the investment, helped me to stay grounded and remain true to who I really am.

I have intentionally sought out and found a small church community because it is important to me to know people in my community and to be known—in the flesh. I actively seek input and wisdom from people I trust and seek the counsel of the Holy Spirit and wait for the Lord’s timing, remembering that patience gives birth to wisdom.

In a culture obsessed with hustle, optimization, and productivity, how can the concept of calling resist being co-opted into just another form of striving?

I really think that my central thesis—that calling comes from outside ourselves, from others—offers a natural balance to the hustle ethos. Because in the end, it’s not all in your hands.

Are there fictional heroes who exemplify a life responsive to calling—or someone who refuses their calling? Give us some examples.

My favorite examples are ones I include in the book.

Jane Eyre is exemplary for me of a character who is tempted to pursue good callings she isn’t meant to fulfill. In two cases, these callings are good—they just aren’t good for her. And in one case, the calling is not at all good—and yet it is the one most tempting to her. She realizes, however, that to follow this invitation would be a betrayal of her deepest beliefs. So she gives up everything just to be true to her faith and resist this call. She pays a great cost but in the end finds her right calling at the right time.

The other example, in this case a negative one, is Willy Loman from Death of a Salesman. The culmination of this entire play is the illumination that Willy’s tragic failure and death owe to the fact that he pursued someone else’s calling rather than his own.

Another character I think a lot about in this context is Thea Kronborg in Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. In some ways the complicated and meandering journey of this gifted singer perfectly reflects the various tensions and contingencies I address in You Have a Calling. This novel is the artistic embodiment of my propositional treatment. I think it illustrates everything I say and more.

You’ve written across genres—criticism, memoir, cultural commentary. How has your own sense of calling shaped the kind of writer you’ve become?

My passion is literature. I love it for its own sake and for how it shows us so much truth about life in beautiful ways. My calling is to teach. It’s what I was “wired” to do. My writing has intertwined all of these things: it models (I hope) the way literature and art teach us about life through aesthetic experience.

As I argue in the book, we are all called to pursue the true, the good, and the beautiful. There are many ways we can each do that. I am trying to do that in all the ways that I teach, write, and work.

“We are all called to pursue the true, the good, and the beautiful. There are many ways we can each do that.”

—Karen Swallow Prior

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal to discuss the topic of vocation and calling. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

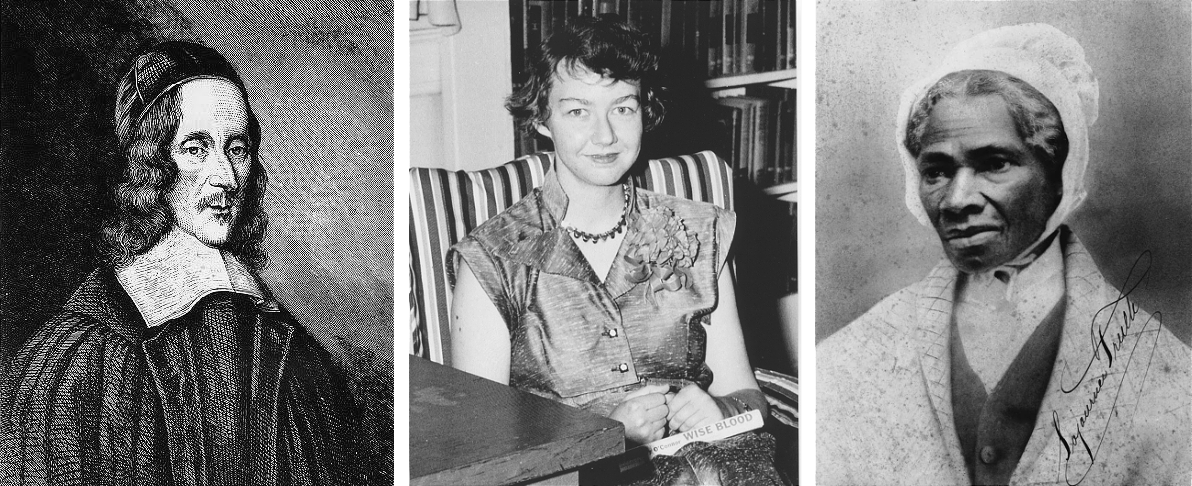

Well, of course, I would want George Herbert there, the seventeenth-century poet-priest who struggled mightily with both of these callings. And I would find any opportunity to sit down with Flannery O’Connor. She had some interesting things to say about her calling as a writer, so she’s perfect for this party.

But I’m not sure I know of anyone in history who had a stronger sense of calling than Sojourner Truth. So she is not only invited but gets to sit at the head of the table.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon, share it with a friend, and 💬 discuss it in the comments below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

Make sure to tour my new book, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future, and discover the preorder bonuses!

KSP is one of my special favorites (if I’m allowed to have favorites…I guess if I’m not ranking my children, it’s OK☺️). I enjoyed this good, true, and beautiful conversation immensely! Thank you🙏

I’ve thought about these concepts a lot over the past few years as disability and chronic illness took away my ability to work in a traditional sense, or to pursue many of the things I love and am good at. What does it mean to have a calling when you are so limited? When you can do so little? I’ve swung back and forth between seeing so much purpose in my very small acts of knitting a sweater for someone I love, or writing a letter, to discouragement that I don’t get to follow my passions or use my gifts like I used to. I’ve wondered then, if this book is for me! I consider my calling a lot. But what does it look like for someone like me?