Is the Nonfiction Book Crisis for Real?

And Are Podcasts to Blame? The Panic Makes for a Good Story. But the Numbers Tell a Different Tale

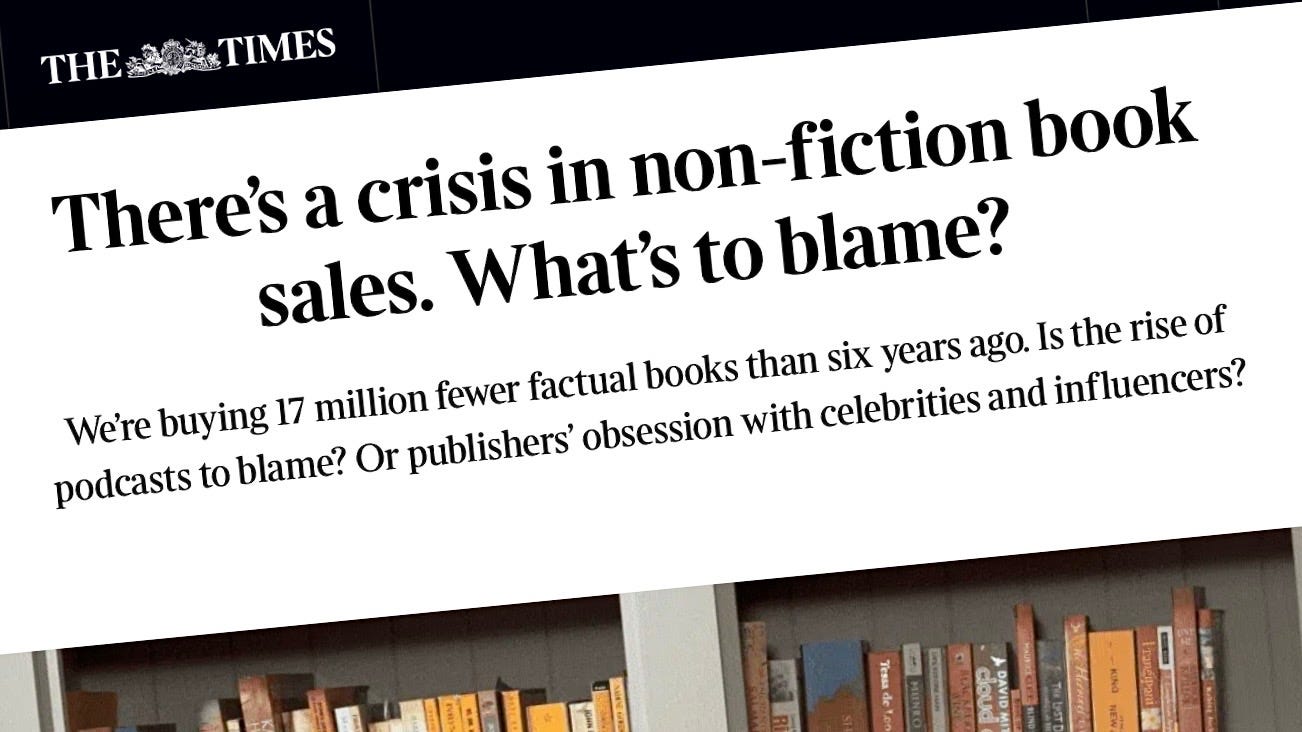

The Times of London recently ran a gloomy piece of publishing news: “There’s a Crisis in Non-fiction Book Sales. What’s to Blame?” Readers are, says the article, buying millions fewer “factual books” today than in years past. The reason? Podcasts.

Other outlets reported slumping sales before. Last year, NielsenIQ reported an 8.4 percent drop between the summers of 2024 and 2025, a stat reported by The Bookseller, The Guardian, and The Week. These articles were largely probing, the latter two both citing podcasts as a possible culprit.

But by the time the Times piece ran—which actually cited a slightly less terrible NielsenIQ number of 6 percent for year-over-year decline—the panic had set in, and podcasts found themselves fingered for the crime, a dripping axe photographed in their bloody grip. “If you want a picture of the future,” wrote Sam Leith in The Spectator, “imagine a podcaster stamping on a shelf of books—for ever.” (Easy on the Orwell, Sam.)

Ghastly news, and perversely appealing for those who already suspect that nobody reads serious books anymore. Unfortunately, the data bugger the thesis. So, let’s just breathe into a paper bag and consider some numbers.

Start with the U.S., where we have the clearest long-run series.1

Boom and Less Boom in the U.S.

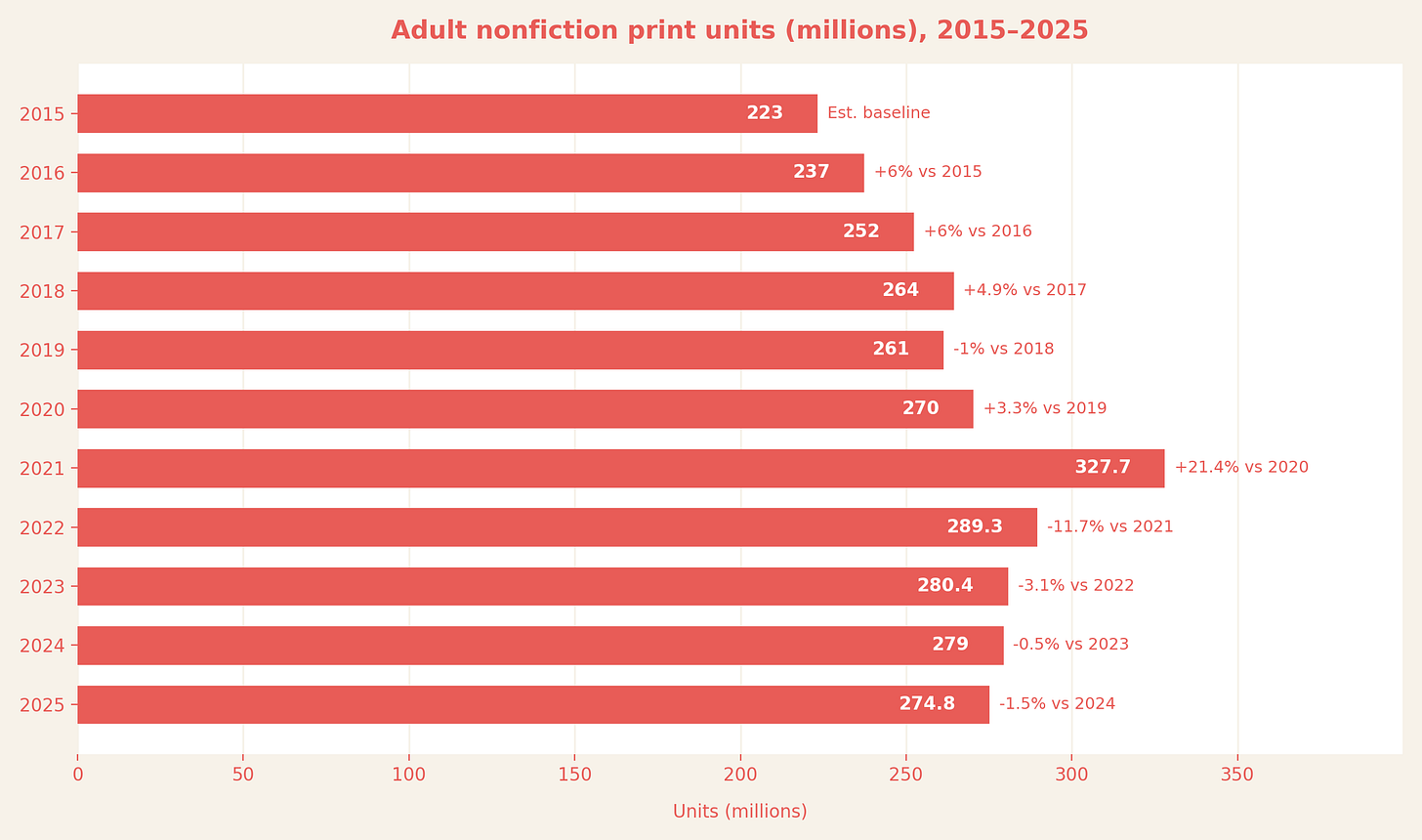

From 2015 to 2019, total U.S. print book units rose from 659 million to just under 700 million, according to estimates from publicly available BookScan data.2 Adult nonfiction was the largest category through this period, flush with political books, self-help, and practical titles, rising from 223 million units to 261 million. Then? The pandemic hit, and everything spiked.

In 2021, U.S. print hit an all-time high of 839.7 million units with nonfiction representing nearly half that number; total nonfiction (adult plus juvenile) reached 401.9 million print units in 2021 with adult nonfiction comprising 322.6 million of the total, later revised upward to 327.7 million. In case we forgot, there were plenty of smartphones and podcasts in 2021; still, one in every two U.S. print books sold that year was adult or juvenile nonfiction.

Ah, but what happened next? That’s the entire basis for today’s hyperventilating. In 2022, U.S. total nonfiction print fell from roughly 402 million units to about 360.1 million—a decline of just over 10 percent. There’s been slippage ever since. Just focus on adult nonfiction. It slid 3.1 percent in 2023, according to Publishers Weekly, citing BookScan, plus an additional 0.5 percent in 2024 and another 1.5 percent in 2025.

Cue Tom Petty: Now we’re free . . . free fallin’! But are we? Stick with the adult nonfiction numbers, and take a ten-year view of the data.

We ended 2025 behind 2024. But adult nonfiction is still ahead of pre-pandemic numbers, including 2020, which handily reversed the 1 percent dip of 2019. Forget the 2021 spike and the subsequent slips: between 2020 and 2025, adult nonfiction actually grew 1.8 percent. That’s a boom and then a little less boom, not a bust. I’m having a hard time identifying a crisis here, let alone one dire as the Times and Spectator report.

But! you interject—index finger jabbing the air above your head—the Times and Spectator were focused on UK data. How right you are.

The Real UK Story

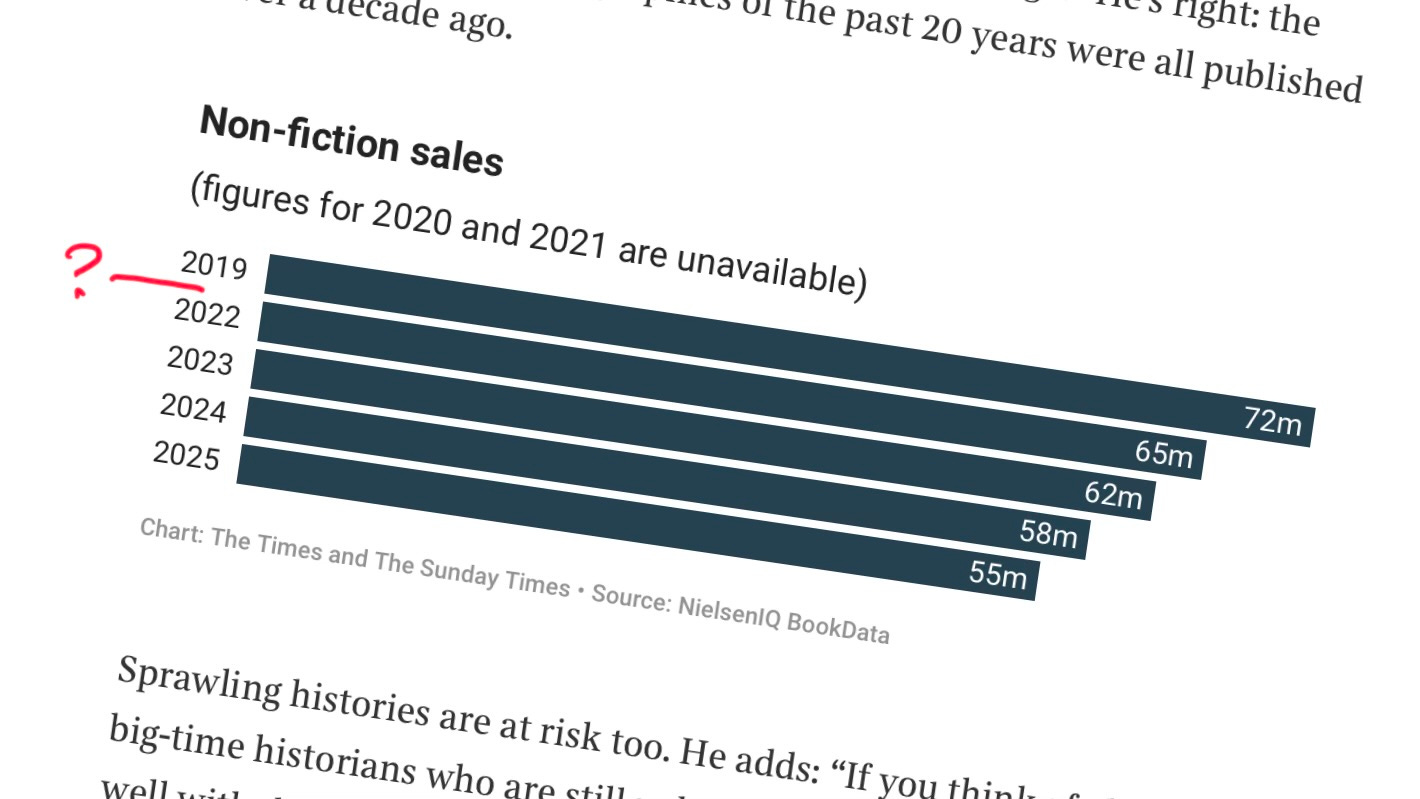

That 6 percent decline? It’s just the throat-clearing before the real bad news. The Times shows UK nonfiction print sales sliding from 72 million in 2019 to 55 million in 2025—a 24 percent drop over six years! Unlike the U.S., where adult nonfiction print remains above pre-pandemic levels, the UK nonfiction market has the footing of a drunk on ice.

But . . . not so fast. The Times chart comes with a revealing clarification: “figures for 2020 and 2021 are unavailable.” Convenient! We’ll just ignore the years when UK book sales hit record highs (213 million units in 2021) and forget that nonfiction joined the party (up 3 percent compared to the same period in 2019, according to Nielsen).

By starting in 2019 and skipping to 2022, the Times transforms a pandemic spike followed by reversion into “years of painfully consistent decline,” which is truthful—if you don’t count the honesty part. A more accurate chart would show not straight decline, but nonfiction rising through the second half of the 2010s, spiking in 2020–21, then falling back.

Still, let’s not be Pollyannaish. UK nonfiction print sales are actually, factually down about 20 percent from a decade ago.3 That’s not nothing. One in five nonfiction books that would have sold in 2015 doesn’t sell today.

So, where did those readers go?

The Digital Offset

All of the handwringing we’ve seen assumes “books = print.” That was sketchy ten years ago; it’s silly today. Nowhere is this clearer than in the same UK data that underwrite the panic. In July 2025, NielsenIQ published a detailed commentary on “the changing shape of the non-fiction market” in the UK. The findings blow a wet, slobbery raspberry at the death-of-nonfiction thesis.

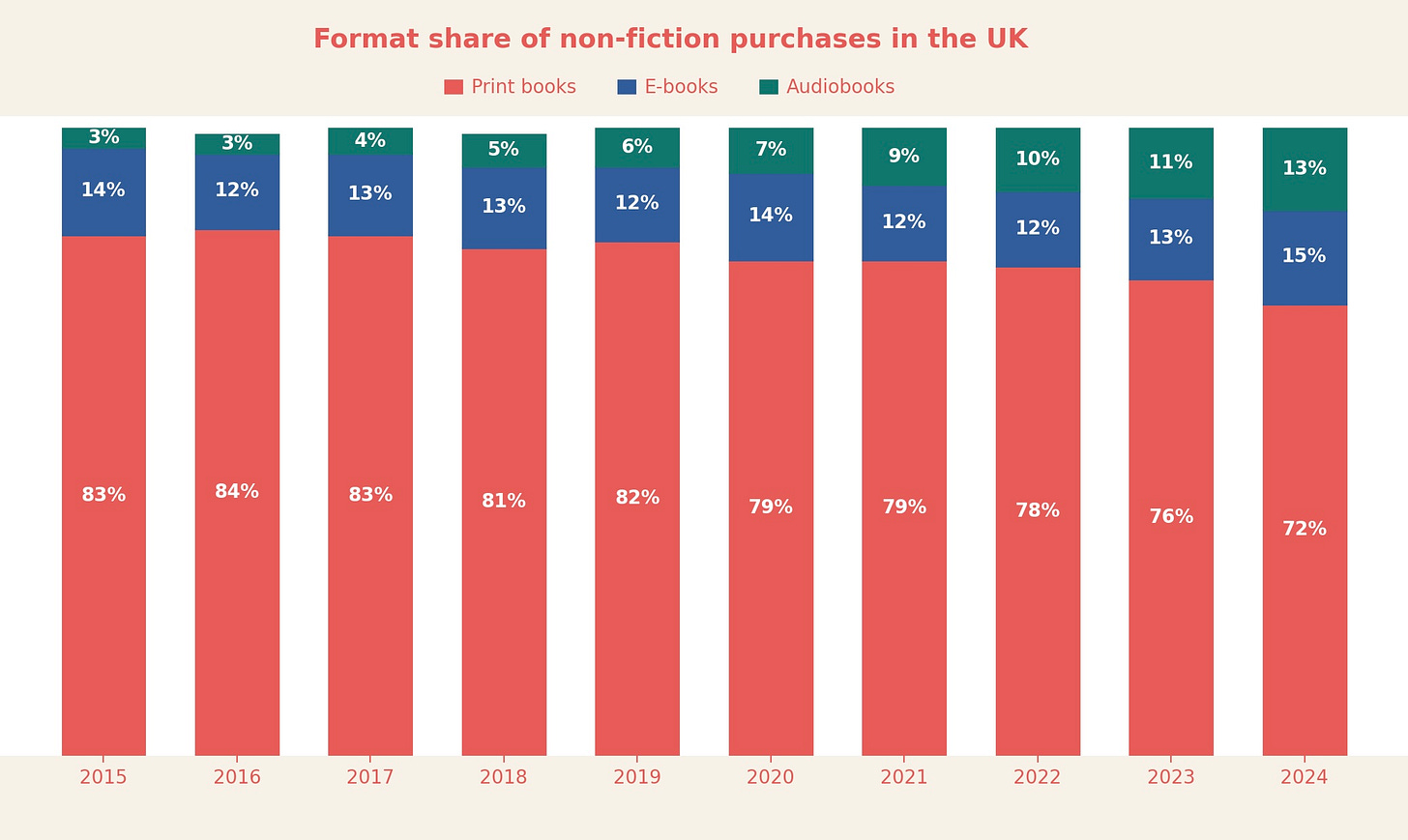

In 2024, UK nonfiction buyers shifted to ebooks and audio at greater rates than ever before, taking a full 28 percent of purchases (ebooks at 15 percent and audiobooks at 13 percent). If we remember that Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs actually wandered the earth and look at format-agnostic revenue, we see a market more or less holding steady while reshuffling formats—not contracting into oblivion. We’re looking at a swap, not a slide.

The Times reports 58 million print nonfiction sales in 2024. If that represents 72 percent of total nonfiction purchases (per Nielsen’s format share data), then total UK nonfiction comes to roughly 81 million units. Compare that to 2015, when print was 83 percent of the market: an estimated 68 million print units would imply a total market of roughly 82 million. That’s 82 million then, 81 million now.

In other words, we’re not in free fall. Over the last decade, total UK nonfiction consumption has barely budged. The “crisis” is almost entirely a format shift—readers migrating from print to ebooks and audio. Where’s that stiff upper lip when you need it?

For what it’s worth, the same basic pattern holds in the U.S., where audiobook revenue jumped 13 percent in 2024, hitting $2.22 billion, according to the Audio Publishers Association. Nonfiction dominates the earbuds: 73 percent of audiobook listeners consume nonfiction, compared to 69 percent for fiction, according to ElectroIQ. In adult nonfiction specifically, digital audio grew 18 percent in 2024 over the prior year.

Finally, one more point worth noting: Nonfiction audiobooks are currently growing at roughly 27 percent per year; that’s a smidge faster than the format as a whole, which is growing at 25 percent. If nonfiction were truly dying—or even experiencing a violent coughing fit—that number would be going the other direction. Turns out people still enjoy learning; they just like doing it while folding the laundry and driving Jimmy to soccer.

So, is the decline real at all, apart from localized ups and downs? At the level of global revenue, the nonfiction market (all formats: print, ebook, and audiobook) was estimated to grow from roughly $13.3 billion in 2021 to around $14 billion in 2022. Just the pandemic spike? No. Analysts projected mid-$15-billion figures for 2025, and Research and Markets now pegs the 2025 nonfiction market at $15.85 billion—right on track—with projections of $17.98 billion by 2030. The steps might be as wobbly as a man reading while walking (don’t ask me how I know), but it’s mostly up and to the right.

All of this makes the question of whether podcasts are killing nonfiction publishing seem a little tone deaf, if not stupid. But, well, people have called me worse, and since I’m already here . . .

Did Podcasts Kill Nonfiction?

Even granting some vibes-level plausibility to the premise of dueling forms of “information audio” competing for the same ears, the evidence bristles at the very suggestion. To see why, it’s worth separating three questions:

1. Are people listening to more spoken-word audio? Yes, unambiguously. Edison Research’s “Share of Ear” surveys have tracked American audio habits since 2014, and over the last decade podcasts have carved out a substantial slice of daily listening, especially among younger adults.

2. Does podcast listening compete with reading time? Not really, and this should be somewhat obvious. People listen to podcasts when otherwise engaging in activities that interfere with reading: commuting, working out, doing chores. Yes, podcasts might displace audiobooks, but the upsurge in audiobook sales tends to undermine that idea. Podcasts are up, but so are audiobooks. If anything, the people who should be griping about podcasts are musicians, not publishers. MIDiA Research found in 2021 that podcast listening comes mostly at the expense of music: more Joe Rogan, less Joe Cocker.4

3. Can we identify a specific, measurable impact on nonfiction book sales? Excuse me while I laugh, but this where the crisis narrative falls down around its own ankles. The timing is all wrong. Podcast listening has grown steadily from 2014 onward, right along with the nonfiction sales I documented above. If podcasts were cannibalizing nonfiction, we should have seen decline during the growth years. And guess what we don’t see?

None of this rules out some substitution at the margin, but c’mon. We’re grownups with brains and everything. I have no idea if my experience is normative, but it’s at least informative: I routinely discover books via the podcasts I listen to: EconTalk with Russ Roberts, Conversations with Tyler Cowen, The Reason Interview with Nick Gillespie, Interesting Times with Ross Douthat, and others. My behavior must be somewhat normative since book publicists would trade a finger for the right booking on major podcasts and happily book their authors on podcasts of all sizes.

Why the Grim Tale Feels True

So why are people slurping down the nonfiction crisis story like the latest seasonal offering from Starbucks?

I’ve got three ideas. First, the peak illusion. The nonfiction pandemic spike was real. And it was a rush, like a nostril full of Colombia’s finest. Unfortunately, it reset everyone’s sense of normal. Even with the post-pandemic slide, nonfiction sales today are still above pre-pandemic numbers. But loss aversion makes us feel like we’re going backward. Collapse feels truer than reversion to the trend, even if the collapse is bogus.

Second, we blame the winners. Fiction—particularly BookTok-friendly fiction like romance and fantasy (gag, gasp, cough)—is doing swell right now. To people emotionally invested in serious nonfiction holding elevated cultural status, that feels like a demotion (cue the sad trombone), even if the absolute numbers remain significant.

Finally, anxiety about attention. The continued success of nonfiction should allay those fears to some degree, but once you’re primed to believe we’re unable to read anything longer than a meme, even a minor, localized downtick in nonfiction can be marshaled as evidence we’ll soon be drowning in our own drool.

The “nonfiction is in crisis” narrative is, in other words, attractive not because it’s supported by real data, but because it tells a flattering story about ourselves—embattled serious readers in a frivolous society going to hell one podcast download at a time. But that story, melancholic and meaningful as it might be, belongs on the fiction shelves.

Thanks for reading! If you want to do your part to shore up nonfiction book sales in 2026, consider picking up a copy of my newest, The Idea Machine: How Books Built Our World and Shape Our Future. Learn more here.

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends (even the ones who prefer fiction).

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Let me start by saying data is a bitch and some of these numbers are a tad squishy. For instance, early reporting on the unicorn year of 2021, citing BookScan (the Circana tracking service, formerly NPD), showed total U.S. print sales at 825.7 million units. But PW cites a BookScan figure for the year revised upward to 839.7 million. Suffice it to say, the figures presented in this article are as accurate as I can muster, and they’re directionally right even with the acknowledged squish. And be forewarned; there’s wobblier numbers to come.

The weakest part of my analysis: I don’t have access to BookScan. But I do have access to whatever figures have been publicly reported, a calculator, and GPT-5.1. I, for instance, estimated the 659 million U.S. print figure for 2015 by working backward from published BookScan growth rates from 2018–2019. I am undeterred.

I couldn’t find a single historical series for UK print nonfiction. With LLM assistance, I derived the 2015 estimate of 68–70 million from total UK print market figures reported by Nielsen BookScan—189.8 million units in 2017, with 2017 described as “basically flat on 2015” and representing a “2.6 percent decline” from 2016. Using nonfiction’s approximate 37 percent market share (calculated from the 2019 figure of 72 million out of 192 million total), this yields 68–70 million nonfiction units for 2015. The 2025 figure of 55 million is from the Times chart. I think what I’ve got is directionally right.

Thank you for such an informative and entertaining piece! These major media outlets have truly become a joke. It’s amazing how often the sky keeps falling in their myopic worldview.

A lot of non-fiction is outdated within a decade - business/economics, technology, science, self-help, even history can become outdated if new historical information is uncovered. So it makes sense why more non-fiction is read in e-format - it is usually cheaper in e-format and a lot more portable - non-fiction can be very bulky in physical format.