Rescuing One Woman’s Life from Oblivion

Gregg Hecimovich on the Role of Historians in Uncovering the Past and Illuminating Our Lives

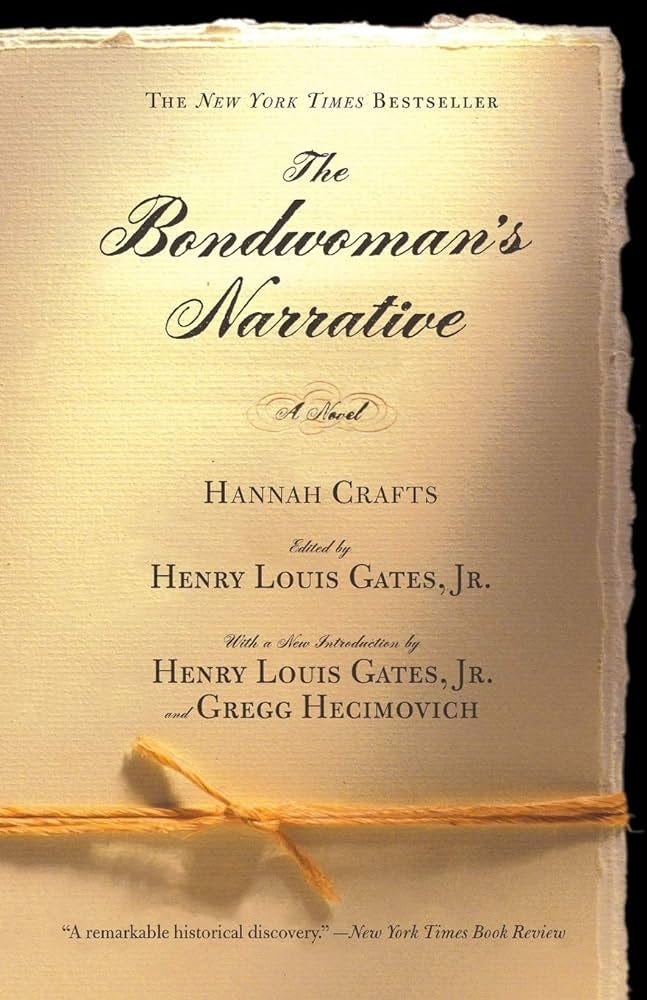

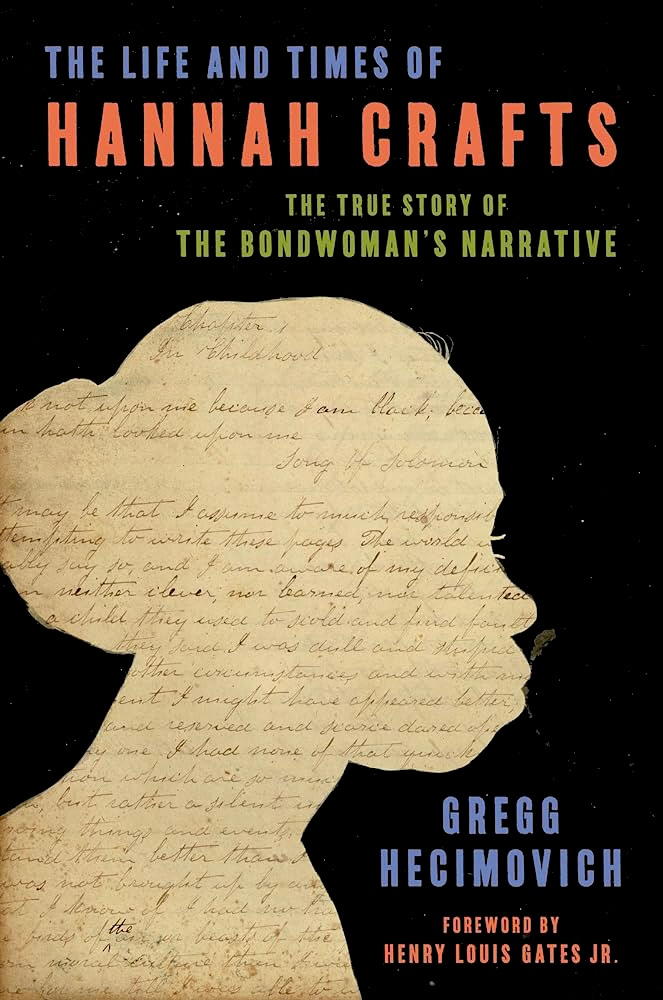

One of the most surprising books I read this year was The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts by Gregg Hecimovich, the story of an enslaved woman who surreptitiously learned to read and then wrote a fictionalized account of her life and escape to freedom in the first novel written by black woman in America, The Bondwoman’s Narrative.

You can read my review here—in fact, if you haven’t, I recommend you do. The Washington Post just named The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts one of the ten best books of 2023.

Crafts’s story would be fascinating on its own, but the intrigue only amplifies when you realize almost every fact about her life had to be painstakingly reconstructed from extensive and intensive historical research. Many scholars have contributed to the effort but none more doggedly or exhaustively than Hecimovich, Hutchins Family Fellow at Harvard University and professor of English at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina.

In this conversation we talk about the twenty-year labor represented in The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts, the challenges in pulling the story together, and the unique role of historians in illuminating our lives.

Miller: What first brought The Bondwoman’s Narrative to your attention?

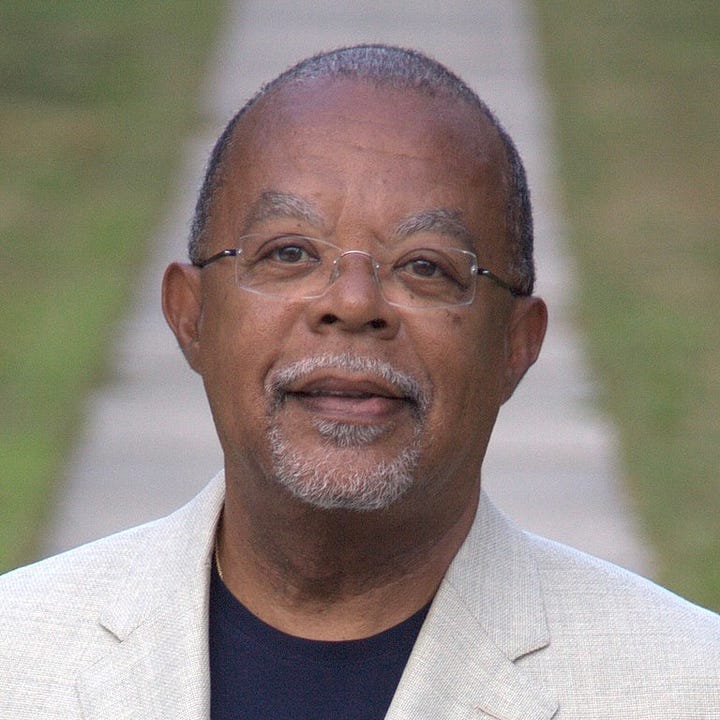

Hecimovich: I was drawn to The Bondwoman’s Narrative, like most readers, when the novel made front page headlines in 2002. Here was an unprecedented publishing event! An author who escaped slavery, and then became a New York Times Bestseller, too. Dr. Henry Louis Gates’s discovery was the most exciting literary find of my generation.

Then I was directly engaged to do some preliminary research on Crafts’s manuscript by Dr. Hollis Robbins, who was interested in an obscure archive at East Carolina University where I taught at the time. Little did I know that Dr. Robbins and Dr. Gates—Hollis and “Skip”—would become some of my dearest friends and collaborators for the next twenty years!

You’re an English professor, but this work goes well beyond even literary history. This is straight-up historical research—not only painstaking archival work but on-the-ground site examination and more. What propelled you to step so far outside your training? Where did the confidence come from?

I was always built to be an archive nerd; that is, a historically focused literary scholar. That sounds fancy, but it is as simple as the fact that I love libraries, especially rare book rooms. When I was an undergraduate at UNC-Chapel Hill, I would join all my friends walking to the football stadium on game days. And then, when no one was looking, I’d sneak away to Wilson Library (across from Kenan Stadium) and into Special Collections. I’d mostly have the library to myself.

It was on one of those football Saturdays that I made my first major literary discovery: a slip of paper that Charles Dickens had published as the first sentence of his novel Our Mutual Friend, but which had been out-of-print since his death. That discovery was the source of my Ph.D. dissertation and the first book that I wrote after I finished my PhD at Vanderbilt University (Puzzling the Reader).

The mystery of Hannah Crafts tugged me into far more exciting and enriching research. One that would pull me into archives in Texas, in New York, in New Jersey, and in Washington D.C.—into every nook and cranny of eastern North Carolina. For nearly twenty years, this research tugged me by the sleeve and led me into engaging descendant communities, conducting interviews, and being present to the people who carry a wisdom and history not maintained in libraries or circulated in scholarly circles.

To write Hannah Crafts’s story was to sit in peoples’ wood-paneled basements and carefully kept parlors and remain open to receiving a history that others had preserved and generously shared. My training for this work came mostly through listening: Listening to the pioneering African American scholars who taught me how to recover the broken histories of black people. By listening to descendant communities. By listening to older members of the locales I studied.

“My training for this work came mostly through listening.”

—Gregg Hecimovich

I’d like to acknowledge some key people here: Daina Ramey Berry, Elbert Bishop, Stephanie Camp, Walter Cray, Marva Dixon, Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Edda Fields-Black, P. Gabrielle Foreman, Marisa Fuentes, Annette Gordon-Reed, Thavolia Glymph, Saidiya Hartman, Calesa Hickerson, Tera Hunter, Stephanie Jones-Rogers, Patricia Matthew, Tiya Miles, Warren Eugene Milteer Jr., Jennifer L. Morgan, Blair L.M. Kelly, Imani Perry, Joanna Reed, Glenis Redmond, Christina Sharpe, Arwin Smallwood, Benjamin F. Speller, Brenda E. Stevenson, Rhondda Thomas, and Isabel Wilkerson.

Hannah Crafts led me on this journey, but the black scholars and community members noted above taught me how to follow her path.

How much does luck play into the discovery process? What are some lucky breaks that determined the shape of your understanding?

I think the whole adventure feels like luck. The way the manuscript came down to be possessed by Henry Louis Gates Jr. The coincidences that meant that the traces of Hannah’s life did not perish. Indeed, The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts consistently narrates how key clues to Crafts’s life story barely escaped oblivion.

But, in another respect, none of this was luck. I was simply allowing myself to receive a history white Americans tried to bury and destroy. My contribution to the larger story found its foundation in the work of pioneering black scholars who forged the tools necessary for this kind of study, and the descendant communities who preserved and carried Crafts’s story forward (noted above). Without them, there is nothing for me to discover, and no tools to uncover a past for which I was otherwise ignorant.

“I seemed to wake to another dimension that I hadn’t realized: all the ghosts of the past dancing along my daily path in life.”

—Gregg Hecimovich

Hannah Bond Crafts Vincent—each name represents part of her life story and each one unlocks that stage of her life. Can you walk us through these, name by name, and how you identified her?

The author was born Hannah Bond and I identified her and her forbearers through property records, shipping manifests, law cases, interviews with descendant communities, and Crafts’s novel.

She named herself in freedom Hannah Crafts, as I learned from her novel, from personal interviews, estate records, and private letters.

She married in 1858 and took her husband’s surname of Vincent to become Hannah Vincent. As Hannah Vincent, the author became a leading educator in both Timbuctoo, New Jersey, and Burlington, New Jersey, with her identity traceable in federal and state census records, city directories, church records, and school charters.

When I contemplate the amount of work that had to go into reconstituting one woman’s life, I’m reminded of how much history is irrecoverable for simple practical and economic reasons. How can historians and history buffs inspire an appreciation for history among those around us?

I think about this all the time from my own experience. I entered college, as I think many people do, without any real sense of history. I remember learning in my early study at UNC that events form a timeline and that they shape the past and help form the present and future. That seems obvious, but I did not keenly experience the world that way as a teenager.

I remember awakening to life as a continuum in college and it felt profound. I seemed to wake to another dimension that I hadn’t realized: all the ghosts of the past dancing along my daily path in life. Street signs suddenly became interesting to me because I finally realized their names told stories of an invisible past. Like the geography of land, water, and sky, I started to see the unseen forces that created my physical world and marked my presence.

I know this sounds hokey, but I developed in my late teens and early twenties a powerful sense of historical consciousness, and my world became immeasurably enriched in the process.

When I write or teach, I try to share the magic of this same spell, so that the past is visible as present, too. My favorite thing in the world is to bring others into this same charmed circle. Our lives already exist rich with an unseen depth, but most people can’t see it. Historians make that darkness visible.

“Our lives already exist rich with an unseen depth, but most people can’t see it. Historians make that darkness visible.”

—Gregg Hecimovich

What’s one insight you wished you could have shared in The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts but didn’t?

After the book went to press, I discovered a 1934 photograph of Willow Hall where Hannah Crafts and her family were first enslaved (depicted as Lindendale in The Bondwoman’s Narrative). I wish that photograph could have made the biography. And I’m still uncovering fresh archival materials, mostly from the friends I made in descendent communities. I can’t wait to share all these new materials with Hannah Crafts’s next biographer.

More broadly, what brought you to black American literature?

The most interesting work being done while I’ve been alive is in the field of African American history and art. I did my book about Dickens’s slip of paper, but I wasn’t interested in continuing down that path. Far more interesting to me is the world I inhabit. And in my world—living in the South—nothing haunts daily life more than the legacies of American slavery. So that is what I teach and write about.

Right now, I’m eight years into my newest book project, The Columbia Seven, where I uncover the forgotten lives and times of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty—seven enslaved people famously photographed in 1850 in Columbia, South Carolina. I built my freshman teaching seminar at Furman University around this project.

This new book is pulling me by the sleeve just as powerfully as Hannah did, and I love bringing students along for the ride. More about The Columbia Seven in this podcast from the National Humanities Center.

“In my world—living in the South—nothing haunts daily life more than the legacies of American slavery.”

—Gregg Hecimovich

Beyond The Bondwoman’s Narrative, what three works published by black American authors before, say, 1930 would you recommend to better understand their world—and our own?

No huge surprises, but these are brilliant and a great foundational start:

Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845).

Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861). The new Broadview Press Edition edited by Koritha Mitchell is lights out!

Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929).

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language are obstacles. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

This is going to be very specific to my own passionate interest in The Bondwoman’s Narrative. I bring these three together the best I can in the biography, but I’d really like to have a celestial meal with all three:

Hannah Crafts

Charles Dickens

Harriet Beecher Stowe

I’d want to hear them discuss their shared art.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post—my review of The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts:

That phrase 'descendant communities' is so compelling and challenging. Some cultures have them, but many don't. Plato feared that the new tech of his day (literacy) would destroy memory and living history. We may be left with chronological data but no stories or values.

I thoroughly enjoyed this interview! Thank you for sharing!