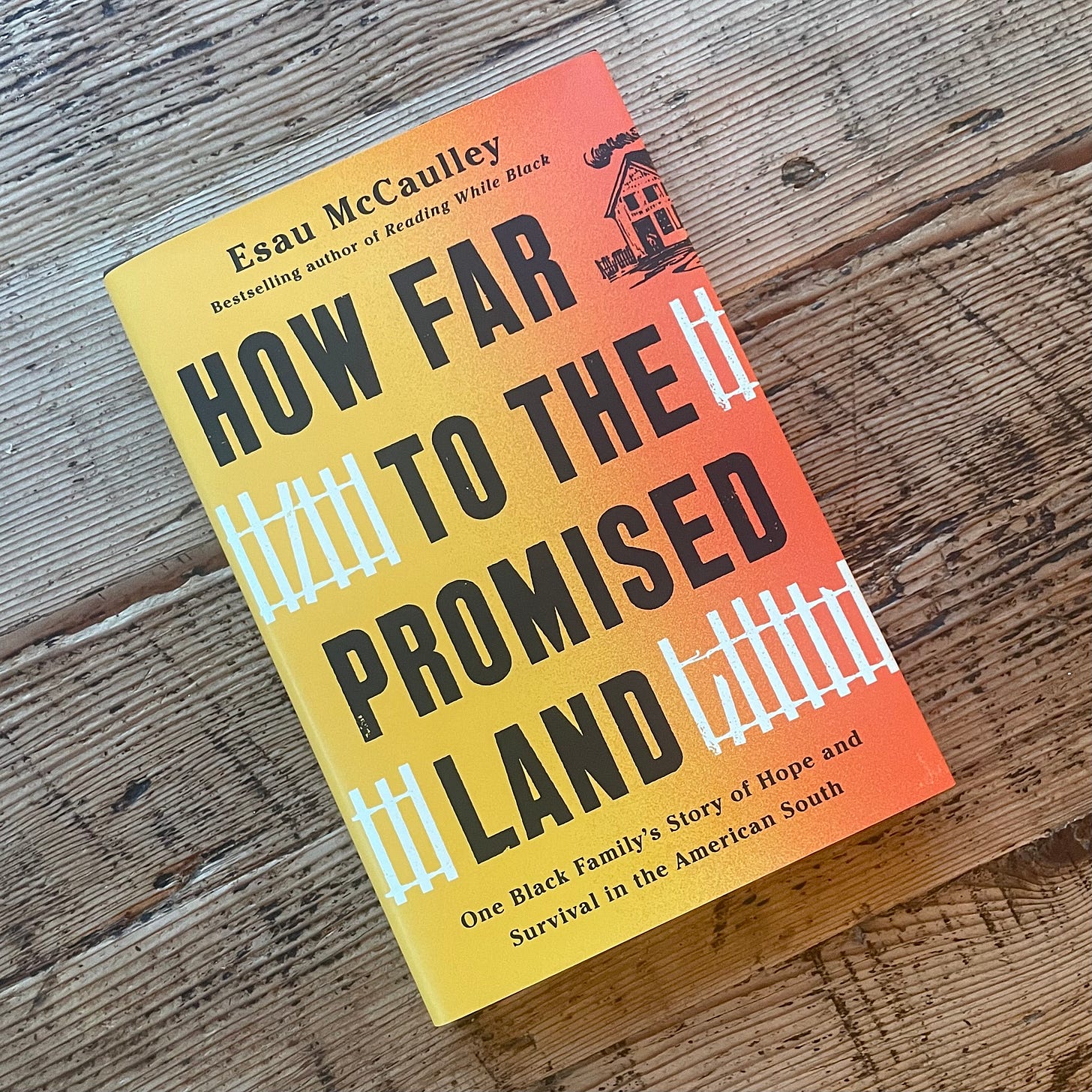

‘A People Born of Trauma and Miracle’

Biography Bigger than One Life: Reviewing ‘How Far to the Promised Land’ by Esau McCaulley

On his next trip, he said they’d go together. The boy, not even ten years old, has badgered his truck-driving father to take him along on his next run. When the big day finally comes, the boy is packed and ready. Dad says he just needs to run to the store to grab some snacks for their adventure.

While Dad runs his errand, the boy goes out front, doublechecks his supplies, and waits. And waits. An hour ticks slowly by. Eventually, Mom comes out. “I don’t think he’s coming back,” she says. The boy can’t accept that and continues his vigil. But then the sun sets, and the truth dawns: His father has left without him.

The boy wheels his bag indoors. “I never,” says Esau McCaulley, “ask to travel with him again.”

Told one way, this story is about what a child endured and how it shaped him. Memoirs usually string together a series of such moments: some sad, some happy, some shocking, some exultant. Enough episodes and you’ve got yourself a book, more or less. But the typical treatment tends to center on one person. Autobiography is, after all, writing about one’s own self.

McCaulley’s How Far to the Promised Land attempts something different. “A good narrative—a Black one, at least—is not owned by any individual,” he says. “It is, instead, the story of a people.” And so McCaulley’s memoir concerns not just himself, but also his own family, extending back several generations. It has to: How else to understand a father who would drive off without his son?

The story opens with the death of his truck-driving dad, also named Esau. (I’ll use Esau Sr. for convenience, but there’s a joke about that late in the book.) Suffering a heart attack one night, his truck veered off an overpass onto the empty street below, killing himself and thankfully no others. McCaulley realizes he will have to deliver the eulogy. Who else would do it?

But then again, why would he do it? It’s not like things improved with his father after he left him literally holding the bag. In fact, things only worsened. Often abusive and crazed by alcohol and narcotics, Esau Sr. raged through his family like a storm and left devastation in his wake. The origins of this destructiveness, as McCaulley notes, goes back to Esau Sr.’s own father.

First, just consider the name: Esau. He’s the bad guy in the biblical story, a sore loser with a violent temper. Who names their son Esau? This dad would, seemingly just out of spite.

“My father died a few months back,” Esau Sr. told McCaulley’s mom, Laurie Ann, when they first started dating. “Right before he died, he told my mother that my brother Barney and I weren’t no good.” Then, when he took Laurie Ann home to meet his mother Wavon and grandmother Sophia, his grandmother told him point-blank he didn’t deserve a such a girl. “This boy will be the source of unending trials for you,” Sophia told Laurie Ann.

As a father, I often think about the Gospel account of Jesus’s baptism. “This,” sounds the Father’s voice from above, “is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased.” If words of love and delight shape a certain sort of human, words of shame and disappointment shape another. How much of Sophia’s prophecy was simply self-fulfilled by a man who internalized the hatred of his own family?

But, then, families are a tangle of hates and loves, and Sophia has her own story. A woman known for her prophecies, she somehow didn’t know the man she married would prove abusive. But come payday, every payday, Bud would hit home and beat Sophia till she forked over her earnings, which he then plowed into some of Alabama’s least-reputable backwoods drinking establishments.

Comforted only by her faith, she prayed for deliverance. “Sophia talked to God the way a person might converse with a close friend,” says McCaulley. “She called on him to keep his promises in the same informal English that she used to scold her unruly children.” Bud’s fortunate God talked back—at least once.

Beaten and left lying on the floor after an altercation, Sophia finally decided she’d had enough. Bud stormed off for a drink and came home to a surprise. Says McCaulley, “Bud returned to find her standing up, a shotgun pointed at his head.”

“I’m going to kill you for what you’ve been doing to me,” she said and then, as she fingered the trigger, heard a voice.

“Do you love me?”

She thought it was Bud. “No,” she said, “I don’t love you. I hate you.” But that’s when she realized it was God talking to her. “Yes,” she said, “I love you.”

“Then let him go,” she heard—and lowered the barrel.

“God has told me not to kill you,” she told Bud, “and right now, I am listening to him. But I cannot guarantee that I will keep listening. Get your stuff and get out. If I see you again, you are a dead man.” No one ever saw so much as his high-tailed backside again.

There’s a push-and-pull, nature-and-nurture dynamic at play here. “Bud was, in part, a product of his times,” says McCaulley. “Jim Crow pressed its knee on the necks of Black men all over the South. . . . But,” he says, “evil cannot be wholly explained by the brokenness of the world. Sometimes we participate in the breaking.” The injured injure, igniting chain reactions of discord of violence.

The force most responsible for dampening the explosions in McCaulley’s family? Next to his bighearted, long-suffering mother, Lorrie Ann, it was the same belief that kept Sophia from pulling the trigger. Faith forms a central theme in McCaulley’s family story. His maternal grandfather was a minister, while his grandmother ran a gambling parlor in their basement—a lesson about how paradoxical life can be.

Plenty of paradoxes and reversals fill McCaulley’s own life: A star high-school football player, he injured his knee and watched his hopes for a Division 1 athletic scholarship evaporate. Though raised in a predominately black neighborhood in Huntsville, Alabama, McCaulley’s injury edged him toward an academic scholarship at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, a nearly all-white school at the time.

But it’s there he also met his future wife, Mandy. He was anxious about bringing his white girlfriend home to meet his family. They accepted her with open arms. Mandy’s family, however, did not accept McCaulley. Her parents even refused to attend the couple’s wedding. But then surprisingly, a year and half into their marriage, Mandy’s parents reached out to reconcile.

“People are always more than the bad decisions they make,” says McCaulley. “As long as we draw breath, there’s always the chance to start anew.”

Would that also hold true for his father? Their relationship had few reasons to improve. Esau Sr. had moved away, been in and out of trouble with law, and worse. Using his son’s identity, he racked up $15,000 in credit card debt he had no intention of repaying. That’ll ding your trust. But the two eventually reconciled as well. It’s how McCaulley knew he could offer the benediction at his father’s funeral—because, yes, that’s coming.

Before his father dies, the two share a fascinating exchange about their common name. It’s an odd one, right? As mentioned, Esau’s the villain of the story, Jacob the hero. But, of course, it’s complicated because Jacob is also a liar who takes advantage of his brother and Esau eventually comes around.

“Dad, I’ve thought most of my life about the name we share,” he said.

I have never in my life met another person named Esau. In elementary school, kids used to make fun of me for it. . . . The kids in church would ask why I was named after the loser in the Bible. For a long time I believed that I was destined to ruin my future with some life-changing mistake, like the biblical Esau.

Though Esau first threatened to kill Jacob for his deception, as McCaulley explained, he later forgave his brother. “Our namesake was not a failure,” he said. “The biblical Esau was a complicated man who found his way to forgiveness in the end. . . . It’s too late now—Mandy and I are done having kids—but if I could do it over, I’d name one of my sons Esau.”

By taking the larger scope of his full family story, McCaulley found the compassion necessary not only to forgive his father but to understand himself. After all, as he says, “the McCaulleys are a people born of trauma and miracle.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Hello Joel. Oh Esau McCaulley came out with another book--yay!!

I used his Reading While Black [the Bible] as part of my capstone showing the strong similarities between Quaker theology and Black Ecclesial Theology.

Thank you for all of these GREAT book reviews!

This sounds like an amazing memoir. I enjoyed Reading While Black and remember him having a thoughtful and reasoned writing style. I can only imagine the depth he would bring to a personal narrative, will put this one on my list to read.