‘Among the Dragons, There Will Always Be Heroes’

Escape to Safety and Back for a Mystery. Reviewing Wayétu Moore’s ‘The Dragons, the Giant, the Women’

Do you remember where you were in 1990?

In 1990 I was blasting Tom Petty’s “Runnin’ Down a Dream” on my bedroom speakers, drums pounding away. On the other side of the globe, Wayétu Moore’s Liberian town erupted in gunfire. “What is that?” She asked her father when she heard the sound. “Drums,” he answered, trying to hide the frightening truth. “That’s a drum.”

In 1990 I was learning to drive, the first time I wasn’t dependent on my feet or a skateboard to go places I wanted to go. Moore’s feet raced out of her home, toward the nearby woods, her father urging her and the rest of the household to safety, telling the kids they were on their way to see their mom.

In 1990 my mom was busy finishing her master’s in business administration. Moore’s mom was also working on her degree—in New York, 4,600 miles away from her daughter and the civil war that had just plunged their small West African nation into pandemonium and devastation.

The backstory of the first Liberian civil war (1989–1997) involves postcolonial political corruption and the breakdown of artificial and uneasy alliances between tribes that eventually led to regime change and the deaths of more than 200,000 people.

How does a five-year-old girl—on the ground, living through the chaos—understand something like that?

Unanswered Question

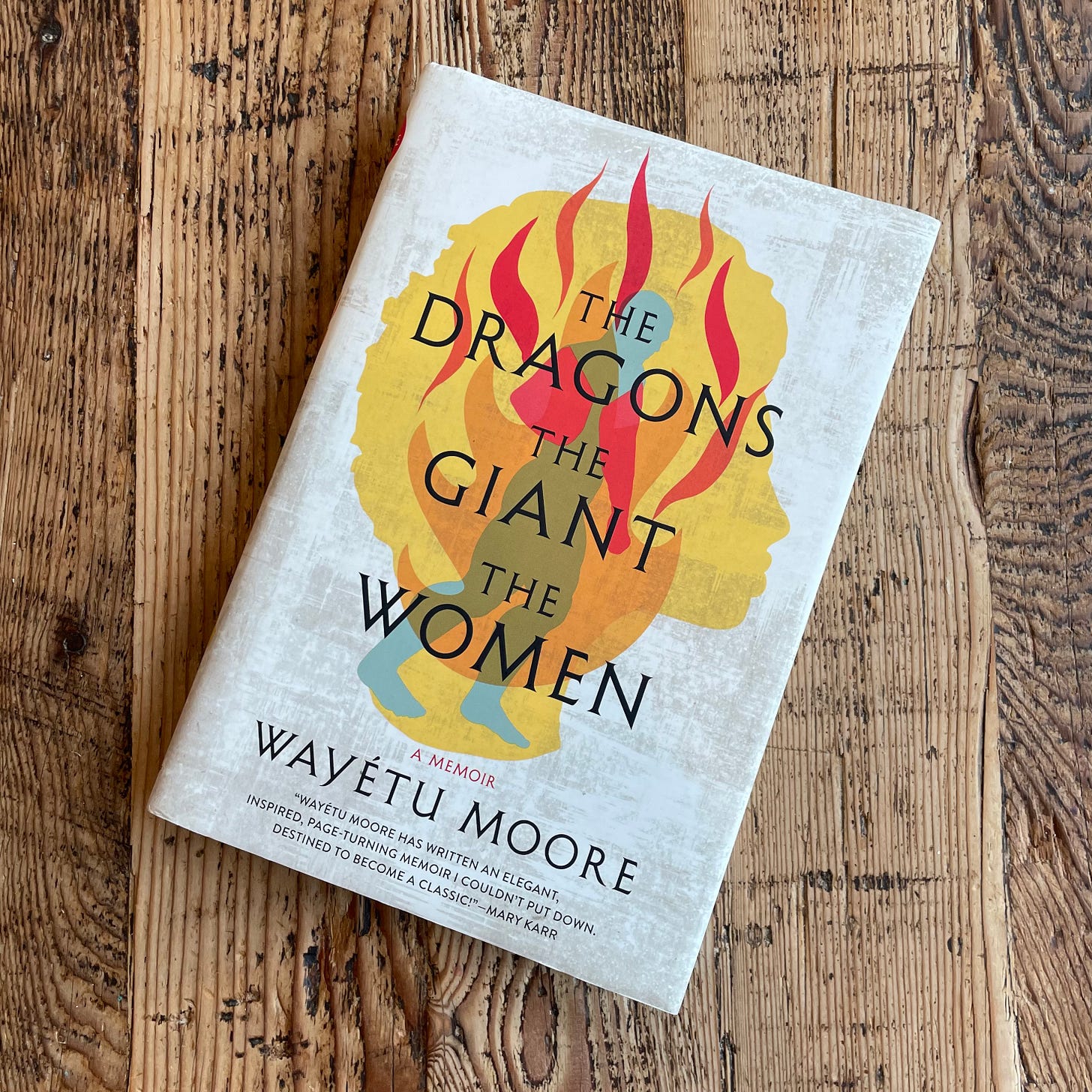

An amazing feature of Moore’s memoir, The Dragons, the Giant, the Women, is how she adopts the perspective of her younger self as she relates the events of the war from which she and her family fled.

“Why is everyone lying down?” she asks her father at the sight of the dead strewn along the roadside, encountered as the family continues their flight to safety. “They are asleep,” he says, adding: “You cannot sleep right now, because we have to go see Mam.”

It was a loving deception—or maybe an elongated truth. Moore’s mother was on another continent only vaguely aware of the seriousness of the crisis. She had no idea her family was running for their lives. But Moore’s father knew how much his daughter missed her mother and wanted to see her.

Moore’s mother is one of the women in the title. The dragons are the fighting leaders of the war. And the giant is her father, who heroically guides his family through one danger and then another until they arrive at a village, temporarily out of harm’s way, though not entirely; her grandfather was murdered for mistaken tribal affiliation while going for supplies.

But “women” is plural for a reason. Another key figure is the female rebel soldier named Satta who locates Moore’s family and, instead of killing Moore’s father as he feared would happen because of his low-level government job, brings them across the border into Sierra Leone and away from the conflict.

An enemy who saves their lives.

What compelled her to protect them? The unanswered question plagues Moore into adulthood and follows her across the ocean to the United States where her family eventually settles for a time.

Life in America

Moore’s adjustment to America proves difficult. As a young girl on a fall day in Connecticut, she can’t fathom why a boy would dress top to bottom in red with horns and a tail. “Caaan-dy,” she tries mouthing the words of the kids buzzing around her. “I realized that I sounded as different to them as they sounded to me,” she remembers.

They didn’t do Halloween in Liberia, and Moore’s Christian parents didn’t approve.

“Some things in this country are not good,” her mother says. “The people dress their children like devils and witches, and take them around to beg for candy. . . . It’s not a good day.”

The family moves to Texas, and Moore finds her footing in her adopted country. Sometimes the new reality is as hard as the adjustment itself. In one instance, she’s chased out of a convenience store with her friends by a man shouting the N-word. America’s uneven and uneasy relationship with race follows her to New York and complicates her romantic relationships as an adult.

And somehow the memory of Satta keeps coming to mind, even after her parents decide to move back to Liberia. She dreams of chance details from the moment the woman emerged from nowhere and rescued them. “Liberia lived with me every night,” she says, “in my dreams. . . .”

She talks to her mother about Satta. She has no answers. But she doesn’t stop her when Moore says she wants to come home, to return to Liberia and find answers.

A Mystery Unraveled

As Liberia heals from its first civil war and a second in 2003, locals seem reluctant to talk. Who did what to whom and why are questions best left unasked and rarely answered. And it turns out her mother has secrets, too.

There are three primary voices in Moore’s narrative:

hers as a child during the war,

hers as an adult long after, and—most surprising—

her mother’s during the war while studying at Columbia University, pregnant with Moore’s little brother after a brief visit home to see her husband, and seemingly powerless to locate or help her family halfway around the world.

But only seemingly.

This fictional voice, which must have been based on conversations with her mother, takes over the book near the end. It details the challenge of being away, discovering her surprise child, and managing the angst of not knowing the fate of those dearest to her. She can’t sit still.

Father had said they’re on their way to see Mam, but Mam is on her way to get them, closing the gap on his elongated truth.

Arriving in Sierra Leone with little money and no plan beyond prayer, she manages to share her story with a fellow bus passenger who takes an interest. “I want to help you,” he says, improbably. “I know of a woman. A rebel.” This woman has been known to help smuggle people to safety, he says, reassuring, “not all fighters are bad.”

What’s more, this woman belongs to the same tribe as Moore’s mother. Her name? Satta. And, says the man, “if you pay her enough money, she will go and get your family for you.”

Her family is across the border, under persistent and imminent threat, and here’s a chance to save them—by hiring an enemy combatant with no assurance beyond a stranger’s word. It’s beyond risky, but what other option does she have?

She’s in.

Reunited

Moore’s mother meets with Satta and gives her a picture of herself and her husband’s newborn son. “He will not go with you unless you show him that picture,” she says.

Satta, true to her word, finds Moore and her family and helps bluff their way back to and across the border. After crossing, she points out where they can find Moore’s mother and recedes from the story—forever a memory and little more. The joy of their reunion is palpable.

Moore’s beautifully written, artfully constructed memoir is a reminder that everyone has more agency than might at first seem obvious, even to themselves.

“There are many stories of war to tell,” she says. “You will hear them all. But remember, among those who were lost, some made it through. Among the dragons there will always be heroes.” Moore’s father, the giant, was one such hero. So was her mother, who crossed an ocean to rescue them. And so was Satta, the friend who looked like an enemy.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-15 quotes about books and reading. Thanks, again!

I worked in an up-country hospital in Liberia in the 1970s, and returned for an extended visit in 1985. Many of my friends and acquaintances disappeared in this war; others managed to come to the U.S. I'm glad for this review, and I'm eager to read the book. If you haven't seen the documentary titled "Pray the Devil Back to Hell," it's well worth your time. It tells the story of the Liberian women, both Muslim and Christian, who joined forces to help put an end to the violence.

Wow. I was a senior in college in 1990, heading to med school, head down and unaware of the rest of the world. This is a great article on perspective. Thank you.