Can’t Say It There: ‘Down with Fidel!’

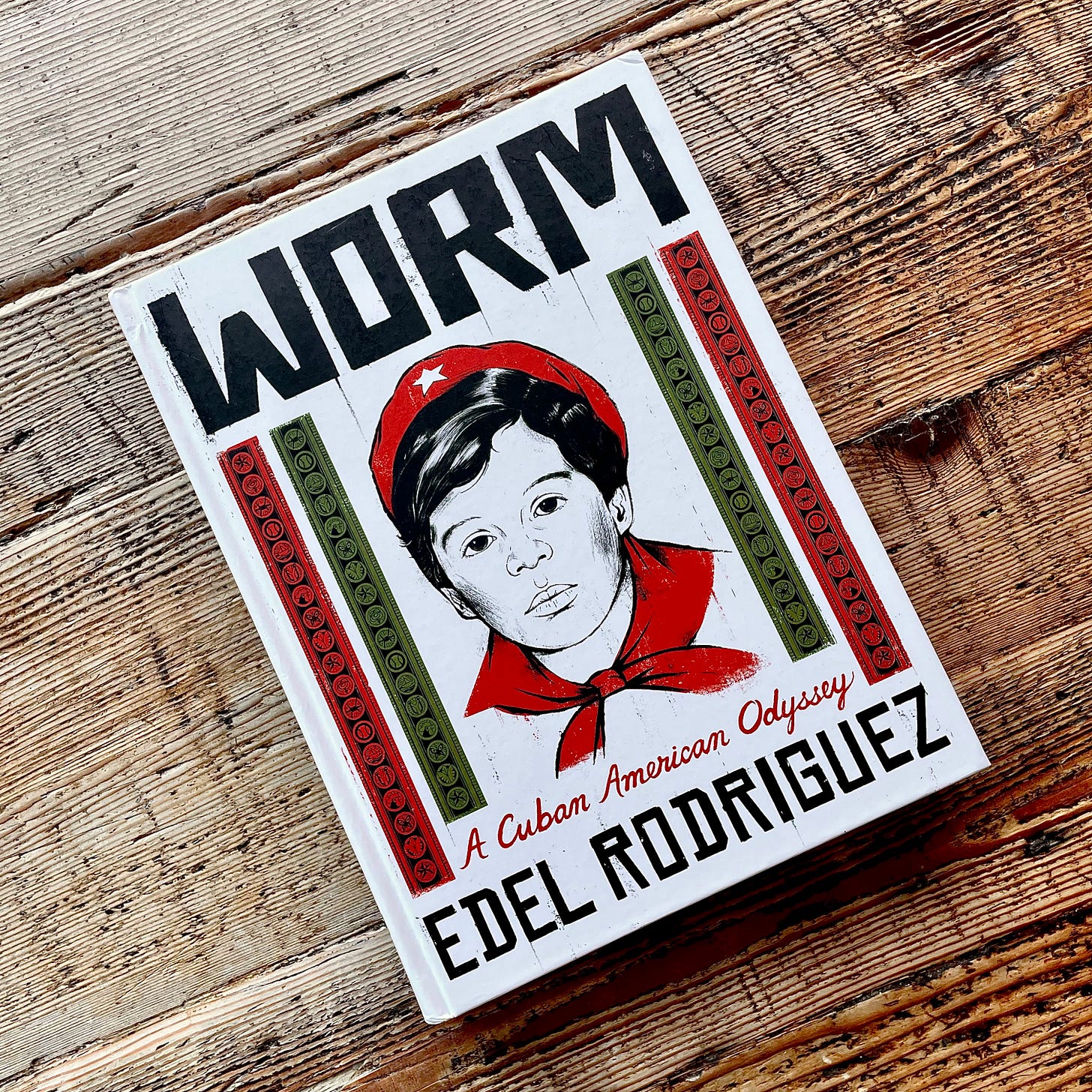

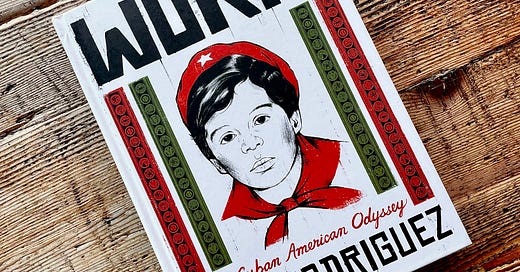

The Revolution Will Be Illuminated! Reviewing Edel Rodriguez’s Stunning Graphic Memoir, ‘Worm’

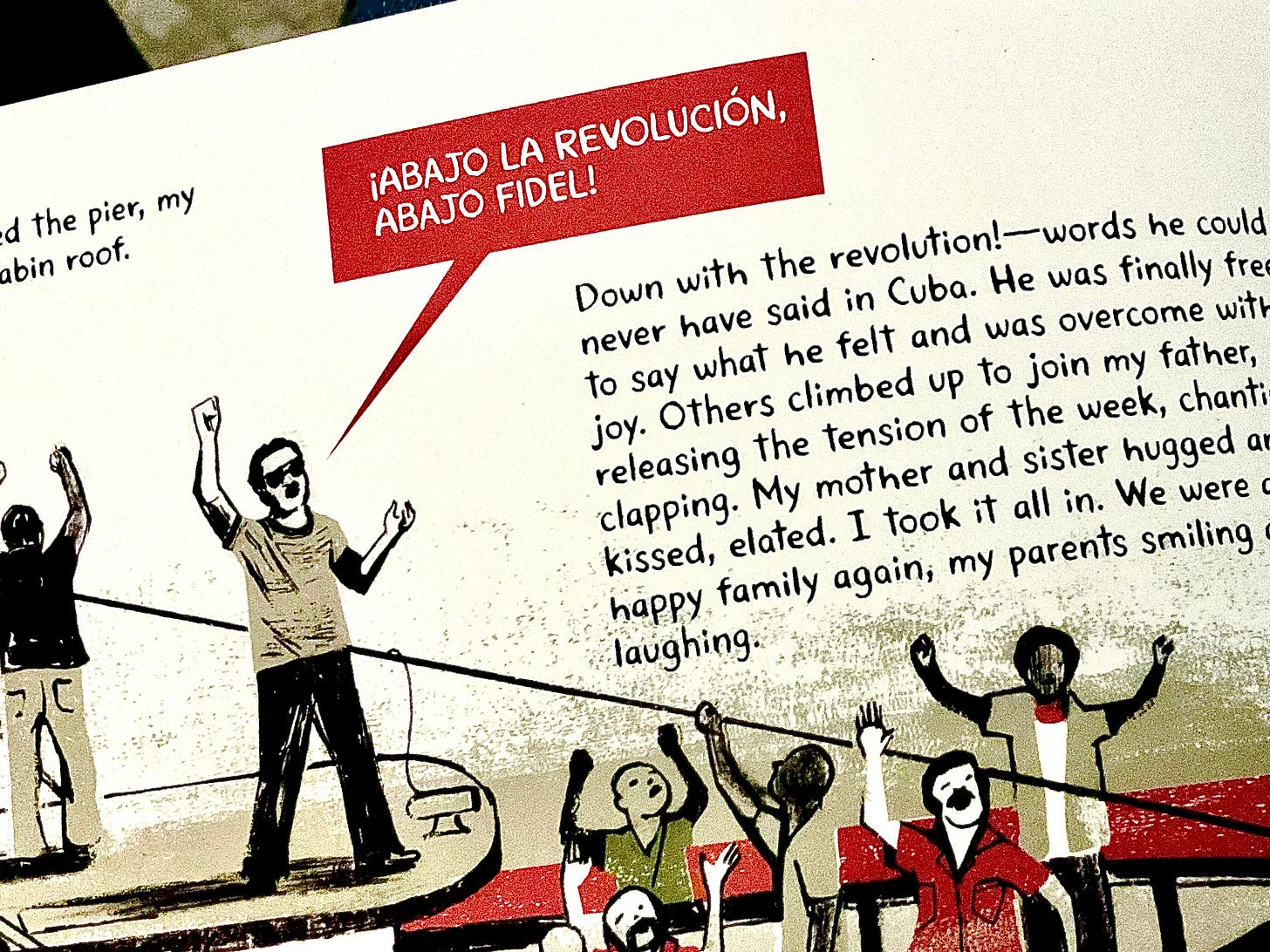

“Down with the revolution!“ said Cesareo “Tato” Rodriguez after fleeing Cuba and reaching U.S. shores in the Mariel boatlift of 1980. “Down with Fidel!” Tato said it here because—as his son, the illustrator Edel Rodriguez, details in his graphic memoir, Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey—he couldn’t say it there.

Edel Rodriguez was born in 1971, a dozen years after Fidel Castro rolled into Havana with his army and changed the trajectory of the nation, a decade after Castro told the world Cuba no longer needed elections and six years after political parties were banned—all but one, that is: the Communist Party.

Repressive Regime

The revolution promised positive change for Cuba’s people, but that promise went scandalously unfulfilled. Economic hardship followed and, as Rodríguez tells it, everything from food to Christmas gifts were rationed by the government. If Islanders wanted or needed anything beyond the pittance granted by officials, they were forced to procure it through the black market or theft.

But worse than the economic restrictions? The social repression.

Authorities insisted neighbors snitch on each other. Castro established local Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) designed to serve as the eyes, ears, and mouth of the state for every neighborhood. Anyone overheard criticizing the government, skirting its rules, or deviating from the party would be reported. Edel’s grandmother would never utter Fidel’s name aloud for fear of informants; instead, she silently rubbed her cheek—code for El Comandante’s beard. As a baby, Edel was baptized in secret because the government frowned on Catholicism.

Tato could see the revolution failed the economically disadvantaged, people like him. He tried finding ways to leave the country. But exit proved impossible, which placed him in a tricky spot. Given his lack of enthusiasm for the revolution, Tato drew the sort of attention that came with prison time.

Edel’s mother had the answer: Coralia volunteered to be the secretary for the local CDR and advised Tato to become the ideologue, an official position responsible for reading Castro’s pronouncements aloud for neighborhood gatherings. “You’re popular, charismatic, and a bit of a showman,” she said. Her plan worked; the official positions helped divert just enough scrutiny for Tato to carve out a life for his family within the repressive regime.

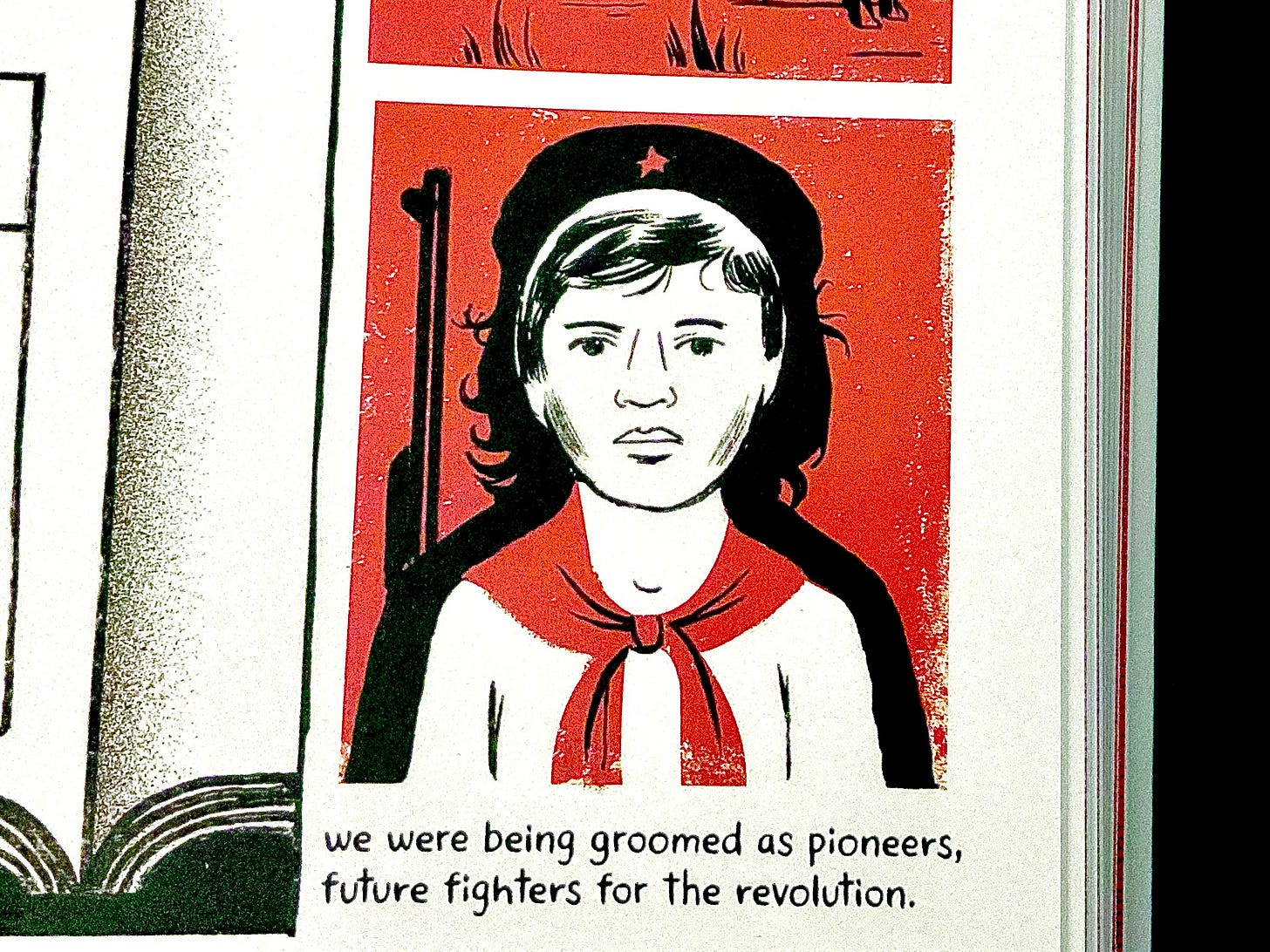

Edel’s life was like any other child’s of the time: playing makeshift baseball with friends, chewing on sugarcane, hanging out with his grandparents, going to school. But school was intentionally designed to indoctrinate children in the ideology of the state. “We were being groomed as pioneers,” he says, “future fighters for the revolution.” The further the education progressed the deeper the brainwashing, drilled in with forced labor and mandatory seminars on Marxist theory.

The indoctrination scandalized Tato told Coralia. “They’re taking all our children,” he told her one night. Plus, there was the threat of Edel being sent off to die in Angola or another battlefield when he got older. What to do?

The Mariel Boatlift

It was possible to apply for Cuban passports but doing so flagged applicants as the worst sort of people—counterrevolutionaries, “worms.” Still, the risk was worth it. They had to leave; there was no future in Cuba, and Tato’s flimsy shield of official protection was evaporating. His side hustles, black-market dealings, and instances of assisting foreigners had drawn the attention of authorities. His file grew thick; prison loomed.

Then, a chance: A spike in political unrest prompted Castro to let anyone who wanted off the island an opportunity to go. All they needed was a boat and they had free passage from the port of Mariel.

It was April 1980. As the announcement came, people scrambled for ships—especially Cubans in America looking to rescue family members on the island. Boats of all kinds headed south from Florida to await their eager passengers. Of course, that much you could get from the history books. But Rodriguez takes you into the experience itself, from the perspective of an eight-year-old boy, as well as his parents.

There was nothing easy about the journey. From the moment a person indicated a desire to leave, authorities pressed them and shook them down, while others—enthralled to the revolution—mobbed and attacked them. Refugees were strip-searched, herded into camps, and forced to wait days with little food while inept officials worked out logistics. Castro tried taking full advantage of the situation; he vacated jails and insane asylums, exiling their inmates along with dissidents and homosexuals, “anyone deemed undesirable.” It was Castro’s one shot to clean house. He even kicked out American journalists.

Over the next several months, about 125,000 Cubans sailed to America on some 1,700 ships. Edel and family came aboard the overcrowded sixty-eight-foot shrimper named Nature Boy. Edel’s mother slipped a coat over his head to keep him warm the night of their journey. And those exiled journalists? A few sailed aboard that same ship, photographing their harrowing hours on the sea.

“As we got closer to land,” says Rodriguez, “people began clapping, hugging, cheering, shocked that we had made it to America.” And that’s when Tato finally let loose his long-held rebuke.

Providential Connections

Rodriguez’s family settled in Miami, Florida, after their arrival. Always resourceful, Tato began a towing business. Edel helped out through high-school, but after his senior year it was time for college.

Edel wanted to go to art school; he wanted to go to New York. His mother opposed the move initially. But Edel was determined to go. Eventually, the plan came together and Rodriguez was able to attend the Pratt Institute. It proved providential in more ways than one. Not only did Rodríguez meet his future wife there, but one of his teachers provided a contact that helped land him a job at Time magazine.

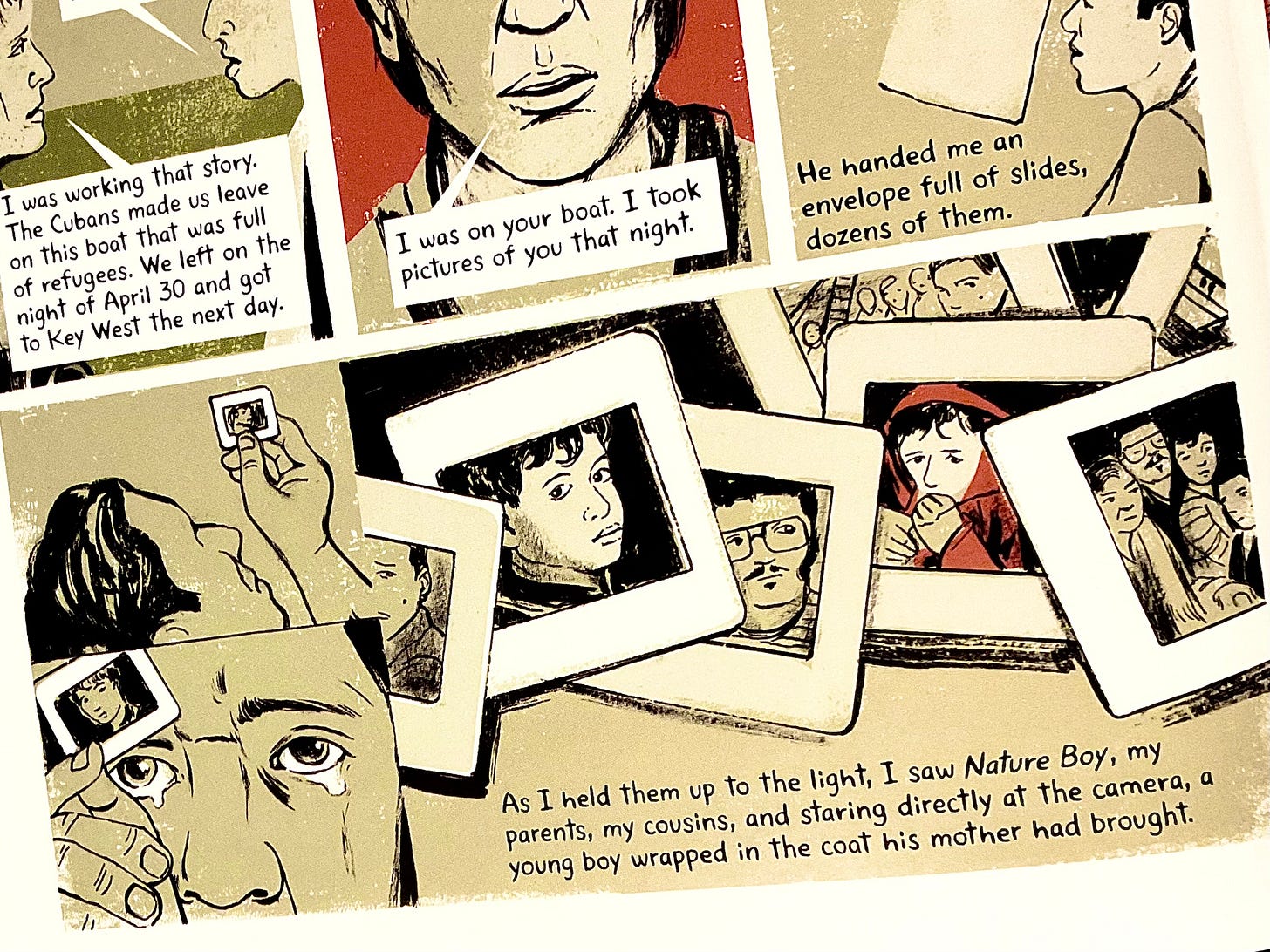

While working at Time, Rodríguez found archival materials about Mariel and met an American photojournalist aboard Nature Boy all those years before. Once he realized who Rodriguez was, the photographer gave him an envelope full of slides from the voyage.

The slides were like a time capsule—or a time machine. “As I held them up to the light,” says Rodriguez, “I saw Nature Boy, my parents, my cousins, and staring directly at the camera, a young boy wrapped in the coat his mother had brought.”

Why would Tato take his family on such a dangerous journey, faced with so many obstacles and perils? The repressions of Castro’s Cuba were too much to endure, and to kick against the goads exposed people to reprisals—including prison and worse. Had his family stayed in Cuba, Rodriguez would have grown up without a father. It’s no wonder he recalls Tato praising the U.S. for its freedoms: “The greatest country in the world.”

Freedom and Its Enemies

When Rodríguez returned to Cuba as an adult for an exhibition with his wife and two daughters, he was warned about bringing books, of all things: “The government might consider them ideological.” For me, living in a country with constitutional guarantees for free expression and no official censorship, fretting over books seems absurd, but sure enough, the books set off alarms as the family’s bags were inspected at customs.

“What are these?” asked a guard.

“Books,” answered Rodriguez.

“What’s in them?”

“Words.”

Eventually Rodríguez was allowed to bring in the books, provided they were only used for his exhibition and not distributed. Couldn’t have unapproved ideas floating around now, could we? As a single scene, it tells the whole story of Rodriguez’s memoir.

For a while there it was impossible to walk an American street without bumping into a Che Guevara T-shirt. The swarm seems to have thinned in recent years, but people still sport the image as an icon of liberation. Do they know Cuba’s history? Guevara was Castro’s lieutenant and charged with implementing various aspects of the revolution. But there was nothing ultimately liberating about Castro’s efforts. He burned books, jailed librarians, and punished—even killed—dissidents and other undesirables.

The illustrations in medieval manuscripts are not typically referred to as illustrations; rather, they’re called illuminations. That’s how I think of Rodriguez’s graphic memoir. It’s a series of brilliant and stunning illuminations, revealing the recent history of Cuba through the life of one boy and his doggedly determined parents. It illumines human freedom and what threatens it.

During the Trump years, Rodriguez became a critic of the president. Whether a person approves or disapproves of his take is irrelevant to the larger point: Rodriguez’s father couldn’t speak a single syllable against Castro while in Cuba, democracy was nonexistent, and dissidents possessed no political freedoms whatsoever. Tato had to reach a Florida beach before he could shout, “Down with Fidel!”

America, on the other hand, welcomes criticism of its politicians. It doesn’t threaten our society. It defines and even elevates it.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

"Under capitalism, man exploits man. Under communism, it's just the opposite." Galbraith

I enjoyed this review very much. Living in a country where a son of a former dictator now rules, Edel’s story speaks to what I fear my country is beginning to forget--the sacredness of human freedom and the pain that ensues when this value is sacrificed to a charismatic but self-interested leader.

We’ve returned to a darker period in our history. And your review makes me wonder whether leaving is the only way out?